Photographers on Photographers: Drew Leventhal in Conversation with Carolyn Drake

My time talking with Carolyn Drake was a fever dream in the best possible way. Talking with artists who inspire you and make you want to work harder can be very intimidating. I know I was extremely nervous when we started our conversation.

But Carolyn had this way of making me feel at ease; I could say what I felt and I could work through my thoughts out loud. In this conversation, we do not talk so much about specific projects that Carolyn has done. There is already a large amount of writing about her amazing photographs in Two Rivers, Internat, WIld Pigeon, and Knit Club. Instead we talked a bit more abstractly about what is behind the images. It was refreshing to hear that complicated emotions, fits and starts of passion, are par for the course as an artist.

I am extremely grateful for the time we were able to spend together. There are infinite paths one can follow. Carolyn’s is unique, a journey we can all learn from.

Carolyn Drake works on long term photo-based projects seeking to interrogate dominant historical narratives and creatively reimagine them. Her practice embraces collaboration and has in recent years melded photography with sewing, collage, and sculpture. She is interested in collapsing the traditional divide between author and subject, the real and the imaginary, challenging entrenched binaries.

Drake was born in California and studied Media/Culture and History in the early 1990s at Brown University. Following her graduation from Brown, in 1994, Drake moved to New York and worked as an interactive designer for many years before departing to engage with the physical world through photography.

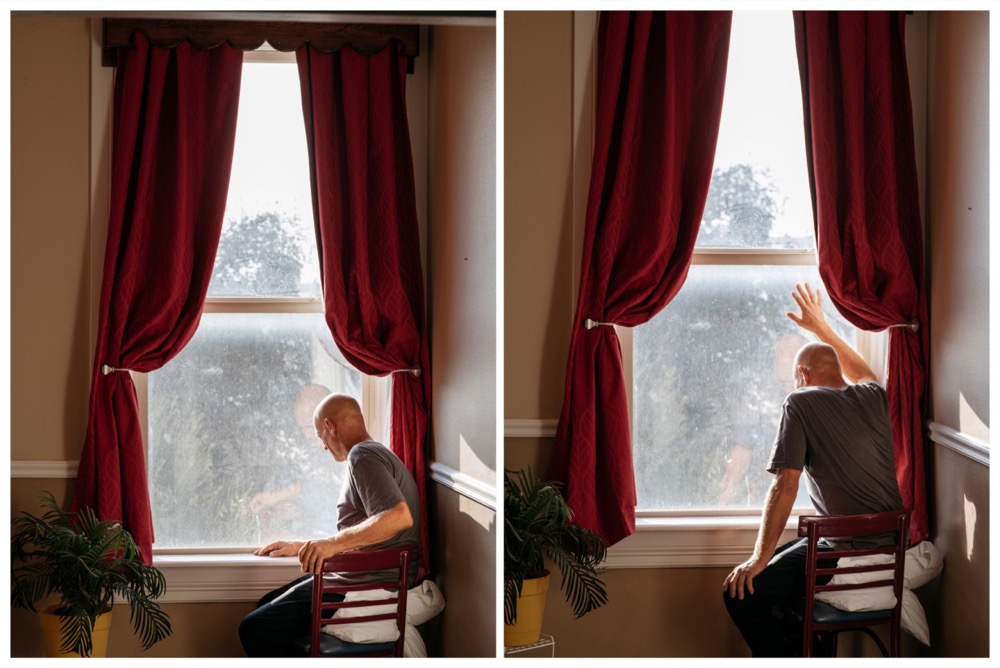

Drake now lives in California and is currently developing self-reflective projects close to home. Her latest work, Isolation Therapy, was exhibited at SFMOMA’s show Close to Home: Creativity in Crisis in 2021 and at Yancey Richardson Gallery in 2022. Her work has also been supported by Peter S Reed Foundation, Lightwork, the Do Good Fund, the Lange Taylor prize, Magnum Foundation, the Pulitzer Center, and a Fulbright fellowship. She is a member of Magnum Photos and represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery.

Follow Carolyn Drake on Instagram: @drakeycake

Drew Leventhal: Carolyn, thank you so much for sitting down and talking with me today. I see a lot of similarities between our practices so I am very excited to hear your thoughts on photography. Maybe we can start with your introduction to photography? I love origin stories that are a bit outside of the usual canon and I know that you came to the medium a little bit later. Could you elaborate a little bit more about how photography became so integral to your life?

Carolyn Drake: Thanks for having me Drew! I talked about this a bit on my podcast with Sasha Wolfe but there’s a lot of things I left out. There’s a weird memory I have about my first camera. My parents gave me a Polaroid camera for Christmas when I was probably ten. I remember my younger sister grabbed the camera and took the first picture before I could get my hands on it and it made me so upset. I don’t know why I was so possessive of it or why it felt like such an infringement. So that’s my first photography memory. There’s another thing that happened when I was young that was kind of special. In seventh grade I had this math teacher who was this really charismatic and odd guy and he loved photography and wanted to share that passion with us. So he converted a closet in the basement into a darkroom and taught us how to develop and print pictures and he would take us on photo shoots – we went to Washington DC at night and learned about long exposures, we did a fashion shoot in a lighting studio, and we took pictures around school. It was pure fun. I never thought that something fun could be what I do with my life. It took me a long time to realize I should try to make that happen.

But I read in your interview Drew about your own experience with photography early on in your life, can you say more about that too?

DL: It’s funny, my story about photography also starts with a Polaroid camera! I was two years old and my parents gave me one of those mini Polaroids. I also remember the pure joy of taking pictures of abandoned cars on the side of the road. It was just something I really connected with but I didn’t realize it until much later when I was in highschool. But again it’s this kind of slow burn, right? So when people say they fell in love with photography at first sight, I actually think there’s a lot more behind that story.

So you do eventually commit to photography in 2001. Can you talk about that early period, from your start in 2001 to 2007 when your first big projects began. What kind of work were you making?

CD: During that time I went to grad school and then I had a couple of jobs and internships at newspapers and at National Geographic. I was making newspaper pictures and learned that that was not what I was cut out for. But I worked on this project for National Geographic photographing the Hasidic community in Crown Heights. Then I went to a newspaper in Florida where I went into a gated community and made a photo project there. I would sneak in and wander around and meet people and it was very much about, you know, getting into people’s lives. Telling stories about other people’s lives is a tricky thing to justify in the world of contemporary photography but that’s where I started. Then I got a Fulbright to go to Ukraine in 2006.

DL: I wanted to ask about that. I am interested in hearing how that time spent in Ukraine and the work you did there changed your path. You’ve spent a lot of time abroad and that was kind of the beginning of it in some ways, right?

CD: It was huge. One of the great things about the Fulbright was that there was a group of us who went together, each with our own research plans, so I connected with those people and I’m still friends with at least one or two of them today. We collaborated and fed off of each other. It was also the first time I allowed myself to think deeper about what I wanted to work on for myself, without thinking about who it was for. I spent several months before the Fulbright researching gender values in the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union split apart in 1991, ideas about gender started changing really quickly and that’s what I wanted to explore in Ukraine. That time researching in advance was so important and it’s something I try to carry forward still, for obvious reasons.

DL: I completely agree, I’ve always felt that our jobs as photographers is to be professionally curious about the world. It’s our job to be curious and to uncover these things that other people wouldn’t notice.

DL: I am going to pivot now to a particular piece you did for the New Yorker in 2016. You photographed along the US-Mexico border. I obviously have a distinct interest in American borders so I was wondering if we could talk about what you saw out there and what you experienced?

CD: That work that I did as a commission for the New Yorker ended up morphing years later into a more conceptual project, a collaboration with my partner Andres Gonzalez. We went to small towns along the border and instead of looking at visible signs of the border or border issues, we tried to think about the crossover that happens in the borderlands. The border with Mexico is often thought of as being highly demarcated, you know, with a giant wall. We tried to steer ourselves in the opposite direction and decided to make pictures of the same things at almost the same time, but looking from different angles, with the plan of eventually putting them side by side to make a whole. We saw a lot of fluidity along the border. In the anthropological sense the borderland culture is this middle ground, it has no beginning or end to it.

DL: Absolutely, this borderland is a buffer zone where two cultures meet. It’s a space of interaction, negotiation and contention, right? The reason I found that piece in the New Yorker so interesting is that anthropology, photography, borders, it’s all about communication. It seemed like you had a really good grasp of that need for communication across borders.

CD: Your work with the Mason-Dixon line is similar in many ways. It is something invisible and unmarked, yet the boundaries it represents, the political boundaries we have in this country, are so pointed. How can we talk across them and communicate with each other? I wonder if in the United States, because a lot of power has shifted away from the federal government and to the states, maybe those boundaries are shifting. Maybe the Mason-Dixon Line is taking on new forms now with the abortion laws and all of the other things happening.

DL: Yeah, it’s a really good point that these state boundaries are becoming much more important. So many of these borders now are fractured and piecemeal, they can become complicated spaces very quickly.

CD: I have a question for you now.

DL: Please!

CD: This is driven by what I’ve been thinking about lately. I have been feeling that my emotions have entered my recent work in a new way. It wasn’t so much like that in my previous work. I feel this anger that needs to be expressed for some reason. So I was wondering, as you research and create about American divisions, if you feel emotions attached to that? I am sure you have had frustrating interactions with people or have questioned your own beliefs. How do you process your emotions around these complicated questions?

DL: That’s a really good question. The Mason-Dixon work was definitely born out of a huge sense of frustration, of me asking “why the hell is everything falling apart and breaking down?” When I go out to photograph I encounter people and beliefs I vehemently disagree with all the time. It can be scary sometimes. In the past few years I have been trying to put my feelings to the side and think more academically or conceptually about what I am experiencing. But what I want to do is actually put more into the work: more emotion, more frustration, more of the fear I sometimes feel. Never in a negative way, but in a nuanced manner. It’s a very good question and it is something I am struggling with currently!

CD: I’m also trying to embrace the emotions I feel in response to whats happening in my life and in the world. As I was sorting through the work Ive made over the last couple years, I tried writing an accompanying text that explores the sources of some of the anger Ive been feeling along the way. Somebody reviewing it told me that “actually, the anger doesn’t come through in your work,” but I decided to use this anger text in the book even though not everyone’s gonna see the anger in the images. I decided I wanted to communicate about the feelings that were simmering beneath the surface of the work.

I think in your previous interview you said something about the work acting as a reflection of yourself and when you’re doing documentary work I think there’s always that question of like, to what degree is it reflecting you? What is it reflecting at all?

DL: This question of authorship and how much of myself is in these pictures is something that I’ve struggled with with this project. The way I see it, my pictures are only one version of the Mason-Dixon Line and so part of it is like the individualization, right? Like this is only the way that I see the Mason Dixon line. If somebody else goes and photographs it next, they’re gonna see it totally differently with different emotions, with different eyes. I struggle with that though. Because in some ways I’m also an anthropologist too, right? And I’m trying to be very real and objective about what I see and who I talk to. There’s that tension again between objectivity and subjective experience and emotion.

CD: Do you know the film Sherman’s March?

DL: I love that movie. That movie is so sloppy. It’s great!

CD: Yeah, it’s sloppy. I thought about it as you were just speaking. It’s another geographic journey, and it’s very self reflective. But you know, one thing I see maybe about you and your background is that you don’t choose one particular place as where you’re from. Like you’re from Philadelphia but also other places. And so maybe your interest in borders stems from that. From not having one identity.

DL: It’s true. We moved around a lot and my dad is an archaeologist and he wanders all the time. So when I was doing some research for the Mason Dixon project, this idea of deep wandering came up and it’s this idea of moving through space, not really knowing where you’re going or what your end goal is, but just paying close attention to where you are and what’s happening. Maybe that wandering is the product of my upbringing.

Would you say your project Knit Club was a result of a similar wandering? Maybe not physically wandering, but a kind of creative wandering?

CD: I think it was. I was working in the South and I was really fighting against how these associations we have with the South are so predefined. I was thinking,”how can I avoid regurgitating the same things and reinforcing the same things?” When you reinforce the stereotype, it just becomes more of a stereotype. And so I was kind of choosing to create something else, maybe you could call it a wandering moment. I felt that there was something else there beneath the stereotypes but I had to approach it from a different angle, that straightforward documentary photography wasn’t gonna bring me where I wanted to go. So I think that’s how Knit Club came about, from a feeling that couldn’t be expressed with the kind of documentary photography that I had come from.

I have always found moments of frustration with photography and the desire to come at things from another angle. I feel like there are things photography can’t do or there are aspects of photography that I want to reject or rebel against. And you know, there’s also burnout. Posing another question for you: I would wonder if/how you experience similar frustrations and how you handle them?

DL: That’s a great question because I’m actually having one of those moments right now. What I have been seeing in museums and galleries, even what I have been making myself recently, raises all sorts of questions in my head about the limits of photography. In many ways I see photography as extremely limited. One thing we have both done to address these frustrations is to diverge into other mediums like sculpture and writing and filmmaking. Having those experiences lets you remember what you love about photography, but it also helps you find the edges of the medium, where it may overlap or abruptly end without an answer.

CD: Okay I have one last question for you. I’m curious how the people you studied with (at RISD or beyond) influenced you and do you have mixed feelings about their influence on you?

DL: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I’ve been thinking about this a lot actually. RISD was the best thing that ever happened to my art practice. It was also extremely difficult. I’ll start with the people that I studied with. My cohort of students had seven people in it and I can’t imagine a better group of people to know and work alongside. I have taken so much inspiration and influence from them.

In terms of the faculty I loved all of my teachers, Stanley, Brian, Steve, Alex Strada, Laine Rettmer. Everyone who taught me is amazing and wicked smart, really good artists. I think in any graduate environment you become influenced by who your professors are, what they’ve read, what they know, what they think about photography. And those ideas really did change me. But I think part of the experience of leaving grad school is slowly breaking away from those influences and becoming your own artist and your own person while still taking what was useful for you.

CD: That happens to a certain degree in the world beyond school as well. We’re always kind of gripping onto influence. There are always influences, you know, and how can you absorb them? You can’t move forward without influences. But how do you absorb them while making it your own thing? Anyway I digress. Drew thank you so much for chatting and letting me turn some of the questions back on you!

DL: Thanks Carolyn, it was a pleasure!

Drew Leventhal (he/him) is a photographer working with themes of colonial history, family, and the ways memory shapes identity. Raised by two anthropologists in Philadelphia, PA, Drew is drawn to the ways photography can be used to reveal narratives about people and cultures in their landscape. His work blends ethnographic fieldwork with an eye for wonder and mystery.

Drew attended the International Center of Photography and recently completed his MFA in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. He was the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize winner and a finalist for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize. He is currently based in Providence, Rhode Island.

Follow Drew Leventhal on Instagram: @drew_leventhal

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024