Atomic Reactions: Paul Shambroom, Ben Huff, Brett Leigh Dicks

Peace keeper silo test launch preparation, Vandenburg Air Force Base, California,1993 © Paul Shambroom

The photographer was thought to be an acute but non-interfering observer – a scribe, not a poet. But as people quickly discovered that nobody takes the same picture of the same thing, the supposition that cameras furnish an impersonal, objective image yielded to the fact that photographs are evidence not only of what’s there but of what an individual sees, not just a record but an evaluation of the world. Susan Sontag

As Sontag states, photographs are evidence of who is looking, and their evaluation of what they see. Paul Shambroom, Ben Huff and Brett Leigh Dicks have each recorded the nuclear landscape, its structures and personnel.

Paul Shambroom’s Nuclear Power photographs of military installations do not fit with our preconceptions. The incongruous scale and human gestures seem random and unconsidered. He reminds us, in fact, that most of us have no actual experience or knowledge of our extensive, virtually invisible, nuclear arsenal. Few of us know what a Command Site is, have never visited one of the 400 silo-based Minuteman III ICBMs spread across the great plains, nor been aboard an atomic submarine. Shambroom’s project is now thirty years old, but the images still raise questions about our defense facilities, as well as concerns about the 13,000 nuclear weapons scattered around the globe.

For little more than 50 years, the previously uninhabited island of Adak in the middle of the Aleutians was a prominent military base. In his project, Atomic Island, Ben Huff explores the footprint left by the government when the locus of geopolitical priorities moves on. His archival and contemporary photographs present evidence of the boom and bust cycles of nuclear proliferation.

For the past decade, Brett Leigh Dicks has photographed the sites and monuments of the nuclear landscape. These have been erected intentionally or have just appeared, unplanned, since July 16, 1945. Dicks’ monuments are iconic forms anchored in boundless landscapes, suggesting sacred sites of power and authority. His relentless views remind us we can never escape uncertain forces in the atomic world.

Ohio class Trident submarine, USS Alaska in dry dock for refit, Bangor Naval Submarine Base, Washington, 1992. ©Paul Shambroom

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock stands in 2023 at 90 seconds minutes to midnight, “..the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been….largely because of the mounting dangers of the war in Ukraine.” I never would have guessed that we would be in this state of nuclear fear and despair when I undertook this project more than 30 years ago.

Nuclear weapons are still one of the dominant issues of our time, long after the end of the Cold War. As we assess the past and contemplate the future, we still have very little concrete visual imagery of the huge nuclear arsenal that has so strongly influenced our lives Between 1992 and 2001 I made 35 visits to photograph more than two dozen weapons and command sites (plus hundreds of individual ICBM silos) in 16 states. With unprecedented cooperation from U.S. military authorities, I photographed warheads, submarines, bombers, missiles and associated facilities throughout the United States.My goal was neither to directly criticize nor glorify. My objective was to reveal the tangible reality of the huge nuclear arsenal, something that exists for most of us only as a powerful concept in our collective consciousness. Psychiatrist Robert J. Lifton wote in his 1986 essay “Examining the Real: Beyond the Nuclear `End'”:

“Given the temptation of despair, our need can be simply stated: We must confront the image that haunts us, making use of whatever models we can locate. Only then can we achieve those changes in consciousness that must accompany (if not precede) changes in public policy on behalf of a human future. We must look into the abyss in order to be able to see beyond it [emphasis mine].”

B83 1-megaton nuclear gravity bombs in Weapons Storage Area, Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana 1995 . ©Paul Shambroom

Decades after beginning this project, almost every type of US weapon, submarine, missile and bomber that I photographed is still active and on the highest level of alert (launch readiness), although in greatly reduced numbers. 2023 marked the 78-year anniversary of the first atomic explosion (“Trinity”), and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. The ending of the Cold War raised great hopes that justification for nuclear weapons would tumble along with the Berlin Wall. Such hopes have proven to be unfounded. Tensions between nuclear powers the US, Russia, and China are at a low point not seen since the Cold War, and all are developing new weapons and delivery systems. Since I began my project, India, Pakistan, and North Korea have joined the “nuclear club” with deliverable weapons (along with the US, Russia, France, the UK, China, and Israel.)

I still hope my photographs will connect viewers to the legacy and current state of these threats, and help them to confront and define their own attitudes about the nuclear past, present and future.

Peacekeeper missile W87/Mk-21 Reentry Vehicles (warheads) in storage, F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne, Wyoming, 1992. ©Paul Shambroom

Paul Shambroom uses found and original photographs to explore American power and culture. His current project “Purpletown” explores communities with razor-thin margins in the last presidential election. Paul’s previous subjects include small-town council meetings, the toxic nostalgia of MAGA, and Homeland Secirty training sites. He’s published three monographs: “Past Time” (2020), Meetings” (2004), and “Face to Face with the Bomb….” (2003), and a mid-career catalog “…Picturing Power” (2008). He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Creative Capital grant, with work exhibited in the Whitney Biennial and collected and exhibited by major museums including the San Francisco MoMA, MoMA (NY), the Walker Art Center and the Art Institute of Chicago. He is an Associate Professor in Art at the University of Minnesota.

Instagram: @paul_shambroom

Delivery of first operational B-2 Spirit “Stealth” long range bomber, Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, 1993 © Paul Shambroom

Adak island served as the westernmost physical front in defense of democracy from 1934 to 1997. In a few short years during World War 2, the previously uninhabited island of Adak in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, bordered to the north by the Bering Sea, was made into the fourth largest city in the territory of Alaska. At the height of the Cold War, six thousand military personnel and their families lived in Adak. In March of 1997, with the Cold War over, the Navy abandoned the island. Today, less than seventy-five people live there amongst the crumbling buildings and fading memory of our past military ambitions.

Ben Huff is a photographer based in Juneau, Alaska. His work explores people and communities living on the edge of wilderness. His first two projects, The Last Road North and Atomic Island, focused on a landscape shaped by the the oil and gas industry and the US military respectively.

His current project, The Light That Got Lost, explores the changing landscape of the Juneau Icefield, and an annual traverse of the icefield by a group of young student scientists.

Ben was an artist-in-residence at Lightwork, in Syracuse New York, in 2014, awarded a Rasmuson Fellowship in 2016, and received Alaska Humanities Forum grants in 2015 and 2016. He has exhibited his work in many solo and group shows in Alaska and elsewhere in the US and Internationally. He currently has photographs in the exhibition From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry Lopez at the Sheldon Museum.

His first monograph, The Last Road North was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2015. Atomic Island was published by Fw:Books in early 2022.

Instagram: @huffphoto

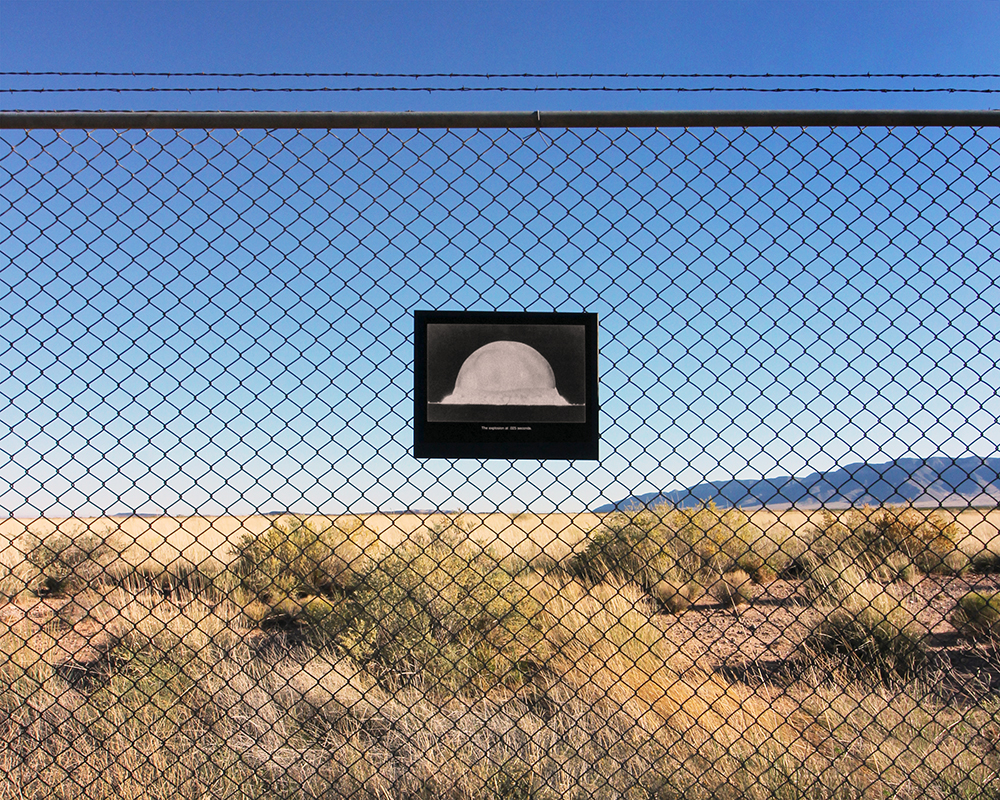

As you pass through the chain link gate at the Trinity Test Site in New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert, the barren landscape sparkles in the morning sun. But there’s more to the twinkling desert than meets the eye. The glittering sand is the result of tiny green fragments of trinitite strewn across the desert floor, an artifact of the ominous events that took place there almost 80 years prior.

Trinity Test Historic Photograph, Trinity Test Site, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, 2018. © Brett Leigh Dicks The United States has conducted 1,054 nuclear weapon tests, of which 219 have been atmospheric. The US Army conducted the first test – a 25kt plutonium infusion device called Trinity – on 16 July 1945 as part of the Manhattan Project in what is now the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert. The test site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and included in the National Register of Historic Places one year later.

Missile Silo Field, Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, Nekoma, ND, 2018. © Brett Leigh Dicks Commencing operations in April 1975, the Stanley R Mickelsen Safeguard Complex was part of the US Army’s Safeguard Program, an anti-ballistic missile system. The complex housed thirty LIM-49 Spartan and seventy shorter range Sprint silo-based anti-ballistic missiles. Armed with nuclear warheads, the facility’s missiles were designed to intercept incoming missiles of foreign origins. U.S. Congress voted to decommission the facility in October 1975, stating that the system was ineffective.

CAPTION Westinghouse Atom Smasher, Pittsburgh, PA, 2023. ©Brett Leigh Dicks Established by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation in 1937, the Westinghouse Atom Smasher was a 5-million-volt Van de Graaff electrostatic nuclear accelerator designed to make precise measurements of nuclear reactions for the research in nuclear power. The nuclear accelerator was located at the company’s Research Laboratories in Forest Hills, Pennsylvania. In 1940 the instrument was used to discover the photofission of both uranium and thorium.

Apple-2 House, Nevada Test Site, NV, 2018. ©Brett Leigh Dicks Part of Operation Teapot, in 1955 a series of 14 nuclear test explosions was conducted in Area 1 of the Nevada Test Site. Designed to formulate military tactics for ground forces on a nuclear battlefield, the Apple-2 test took place on May 5, 1955, to test the impact of a nuclear blast on different types of building construction. The buildings were furnished, stocked with different types of canned and packaged foods, and populated with mannequins. Two structures, now known as the Apple-2 Houses, survived the blast.

CAPTION Shirley Basin Uranium Reserve, Carbon County, WY, 2023. ©Brett Leigh Dicks Wyoming has the largest known uranium ore reserves in the United States. By the mid-1980s the uranium industry was producing material faster than nuclear power plants and military programs were able to use it resulting in the collapse of the market and closure of numerous mining operations within the state. Along with several significant mining operations, Shirley Basin was also the site of a former uranium mill. The mill produced more than 71 million pounds of uranium from underground and open-pit mines between 1971 and 1992.

Brett Leigh Dicks is an American/Australian currently based in Fremantle, Western Australia. He is a social commentator who takes an archaeological approach to photography, primarily exploring the relationship between society and the environment. Using the landscape as a marker of societal change, Brett’s work explores how themes such as dispossession, repression, exploitation, and retribution play out over time. He has documented the legacy of the indigenous mission system, death row and capital punishment, the vestige of decommissioned nuclear missile bases and most recently, the aftermath and wide-ranging impact of atomic energy. Framed within the ethos and aesthetic of the New Topographic movement he presents his subject matter in its topographical state, providing a direct conduit between his subject matter and the viewer. Brett’s work has been featured in over 50 solo exhibitions in Australia, Europe, and North America along with numerous group exhibitions. His work was included the Figge Art Museum’s recent survey of photography in the American West, “The Magnetic West,” State of the World exhibition at Prix de la Photographie Paris, the Sony International Photography Awards.

Instagram: brettleighdicks

Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman are photographic collaborators. As an extension of their long-term examination of the landscape, their new book, BOMBSHELLS, addresses sex and death in the nuclear age.

Website: www.ciurejlochmanphoto.com

Instagram: @barbandlindsaycollaborate

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Re-Discovering Native America: Stories in Motion with The Red Road ProjectMay 5th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Simon Norfolk: When I am Laid in EarthApril 27th, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024