Gerard Gaskin: The CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography

Every two years, the Duke University Center of Documentary Studies offers the CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography. It’s an event, for documentary photographers in particular, that can launch a career, bringing attention to projects that are often under funded long time efforts. The recipient of the 2012 CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography winner is Gerard H. Gaskin, and his book, Lengendary: Behind the Ballroom Scene is now available for purchase.

Every two years, the Duke University Center of Documentary Studies offers the CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography. It’s an event, for documentary photographers in particular, that can launch a career, bringing attention to projects that are often under funded long time efforts. The recipient of the 2012 CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography winner is Gerard H. Gaskin, and his book, Lengendary: Behind the Ballroom Scene is now available for purchase.

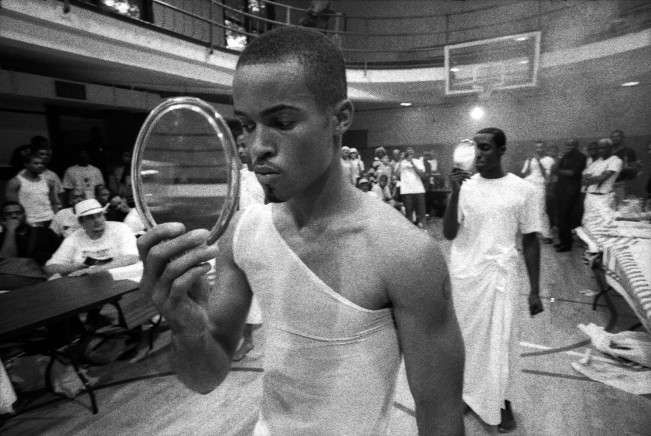

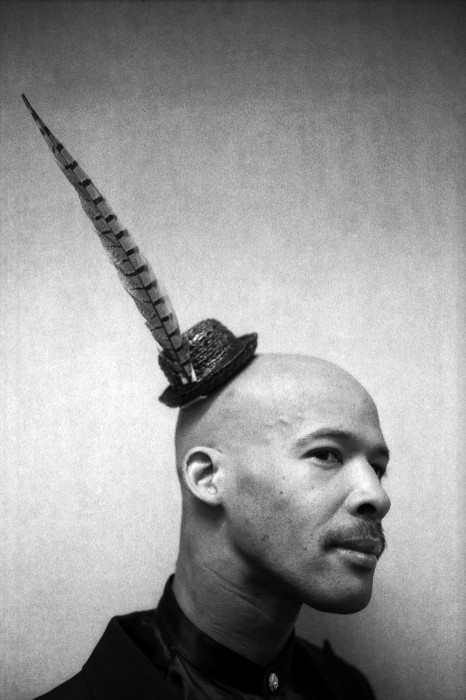

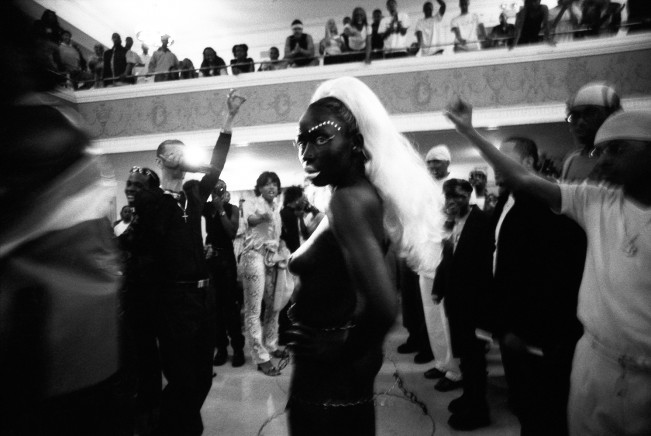

Legendary: Behind the Ballroom Scene takes us inside the culture of house balls, underground events where gay and transgender men and women, mostly African American and Latino, come together to celebrate their recreated selves. Captured in the New York area, Philadelphia, Richmond, and Washington, D.C., the project is a collaboration between photographer and the house members who let him enter the intimate world of ball culture. The book includes an introduction by Deborah Willis (the juror for the 2012 award) and an essay, “The Queer Undercommons,” by Frank Roberts. An interview with Alexa Dilworth of the Center for Documentary Studies and Gerard follows the photographs.

Gerard is a native of Trinidad and Tobago earned a B.A. in Liberal Arts from Hunter College in 1994. As a freelance Photographer his work is widely published in newspapers and magazines in the United States and abroad including; The New York Times, Newsday, Politiken, Black Enterprise, Ebony, King, Teen People, Caribbean Beat and Inc. Magazine. Additional clientele are record companies including; Island, Sony, Def Jam and Mercury records. Gaskin’s photographs have also been featured in solo and group exhibitions across the country and abroad including The Brooklyn Museum, The Queens Museum of Arts, Galvanize in Port of Spain, Trinidad, Goethe-Institute Accra, Accra, Ghana and Imagenes Havana: Fototeca de Cuba Habana Vieja, Cuba. His work is represented in the permanent collections of The Museum of the City of New York and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His work is also featured in the books and covers of books like Transparent (2007), Why I Hate Abercrombie & Fitch (2005) and Committed To The Image: Contemporary Black Photographers (2001). Gerard has won many important awards, grants and residences in 2012 CDS/Honickman First Book Prize, 2011 Woodstock Center of Photography Arts-In-Residence, 2010 Light Work’s Arts-in-Residence in Syracuse, NY. 2005 he won the Queen Council on the Arts Individual Artists Initiative Award and in 2002 he was awarded The New York Foundation for the Arts Artist fellowship for Photography and was part of the Gordon Park’s 90 that brought together 90 of the top black photographers in United States to celebrate Gordon Park’s 90th Birthday.

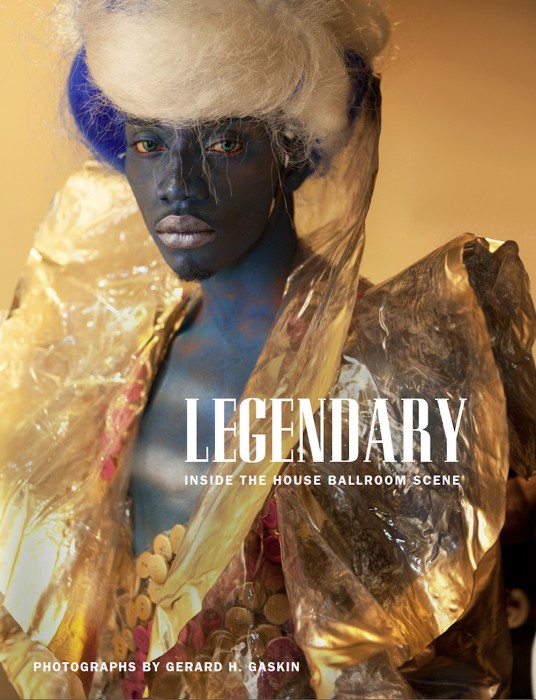

Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene

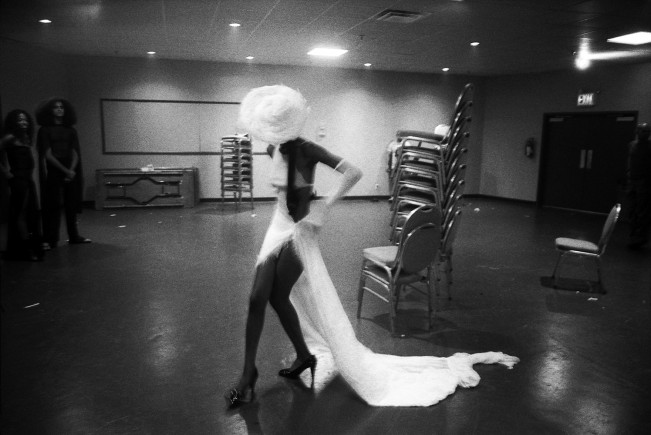

I have worked on this book “Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene” for twenty years. The photographs in it document the performative and aesthetic history of the African American and Latino House Ballroom Community since 1993 to date. Balls began as an underground, hidden form of community building forged together by minority queers who felt excluded from white gay culture. My work covers a period when balls shifted from using club music in the 1980s to hip hop in the 1990s, where hip hop culture created a desire in participants for ‘realness’- the move to transitioning to desired identities. The ‘90s simultaneously mark a certain masculine ideal that took over from the earlier period of femme queen culture. Since its beginnings in 1969 in Harlem, balls have come a long way as they have influenced popular culture through dance forms such as vogue, gained mainstream attention through documentary films like Julie Livingston’s Paris is Burning, and scholarly focus from scholars like Frank Roberts, Edgar Rivera Colon and Marlon M. Bailey carrying out serious ethnographic work on Balls.

The late Marcel Christian, appointed grandfather and historian for House Ballrooms explains, “you can’t go to Paris to do the runway, you can’t go to Broadway. But to become known that’s what it’s all about. The people who participate want to be liked, accepted and loved; they go to the balls to be seen.” This quote captures the spirit of my book and describes the important role that balls perform for young African American and Latino queers, as spaces where they can find recognition and visibility in the context of marginalization. As such, today Balls constitute a tradition of pageantry in the U.S., where working- class African American and Latina/o queer youths from urban inner-cities collaborate to challenge normative sexual and racial behaviors. Such challenges are organized around categories such as: “butch queen sex siren”, “woman’s face” and “executive realness”.

These twenty-three images are a small sample of twenty years of historical and aesthetic documentation, but they capture the formations and representations of new families through houses, which call themselves glamorous names like Blahnik and Xtravaganza. Often ousted by their biological families, these “children” have makeshift “parents,” who are only ten years older than them. By necessity, they perform doctor, shrink, beautician and health-advisor to one another. These parents mentor and teach their children to walk with a switch and act worthy of true pageantry. Often, winning at balls means winning for your family and so these competitions create avenues of self-worth. Family members morph their own bodies to an internal vision of soft curves and high voices. So, though the Balls are ostensibly about fashion and prestige, they are really about building family and manifesting selfhood. These are deep universal themes but with visually compelling feathers and flounces.

My work with the House and Ballroom communities has been showcased in numerous museums across the country and abroad, with the Museum of the City of New York and the Schomburg Library housing some of my images in their permanent collections. As a committed member of this community, I have been part of many efforts that concern it, such as photographing images for AIDS awareness and prevention programs. I see this book as an extension of such past collaborations, and a celebration of the resilience and creativity of a people who have shown enormous courage in the face of adversity.

An interview with Alexa Dilworth, Publishing and Awards Director, Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University

March 12, 2013

How did you become involved in this project? How did it start?

More than twenty years ago I met this guy, Douglas Says, a clothing designer and makeup artist who did work with Jules Allen, a photographer whom I was assisting at the time. Douglas knew all of these major figures in the ballroom scene. He made costumes and did makeup for transsexuals who performed at balls and on 42nd Street. He introduced me to people, and I started hanging out at Show World, and then later at a place called Sally’s II (Sally’s I was called Sally’s Hideaway, that’s where Paris Is Burning was shot, and it burned down). And I started attending balls, which back then only happened about ten times a year. The process began with me just hanging out at the balls. The first year I didn’t take any photographs, though I had my camera on. I got a lot of advice telling me not to take photographs immediately, to wait until the community became comfortable with me. There had been some fallout from Paris Is Burning, because some members of the community did not appreciate how the film came out. Some people felt exploited—their interviews either ended up on the cutting-room floor, or they felt like they didn’t get any return for their involvement in the film.

(Livingston’s film, like my series, started out as a project for school, by the way.) As a result, I was very careful about spending a lot of time with members of the community first; I didn’t make my first

image until 1993.

Why were you interested in this project, in looking at this world?

I was just really curious. I wondered, “Why does someone decide to become a transsexual? Why do people believe, feel so strongly, that they need to transform themselves?” And I am interested in thesafe spaces that balls create, how performers at balls play with the idea of who they are and how they want to “live.” I grew up in a very Catholic home. My mother was a three-day-a-week Catholic. Queerness was taboo in the church, even as I saw it all around me. So questions about innate versus acquired sexuality, about transformation and performance, are of interest to me.

Were people welcoming? How does insider/outsider work in these particular situations?

Some people were welcoming, some weren’t. I’m not an insider. I was probably perceived in the same way that Livingston was—as an outsider, someone coming in who wasn’t a participant, a performer. And I often feel like I’m still perceived in that way sometimes. But I am connected to the community. I’m asked to speak and show my work. When something happens like the fight that broke out at a ball in North Carolina—in Charlotte—I get texts and emails and am part of that chain. So it shifts. I’d say I’m a familiar outsider.

Do you get permission? Do you ever ask people to pose?

There are people I shoot over and over. And then there are the “young and new” people. I’m always wearing my cameras. I want people to see me, know I’m there. Yes, I always ask permission. I makesure my presence is known. And asking people to pose—I do sometimes. I mean, I’ve made dedicated portraits, but I will sometimes ask people to pause, wait a moment, in the middle of things, because I find it quiets things down. In that kind of space, with that many people, it’s impossible to be invisible, so I put myself out front and then move into more of a documentary mode. People are naturally wary; it’s a gay space. But it’s changed a lot over time too. Today, with smartphones, etc., people are used to seeing cameras and being constantly photographed. But while the environment has changed, as a non-gay person in a “gay space,” this question still matters very much, is still relevant.

The whole project is about being collaborative. I participate in the community—I run stuff past a lot of people. I check in about how images are presented, or for instance, how the book title would be interpreted in the community. I have political questions about representation that I don’t want to make alone. I want the reactions and input of others. I know that I have an emotional attachment to certain images that have to do with me—what I was thinking or feeling at the time, or my relationship to the people in the photos. I don’t want that to overshadow the images, so I ask and I listen. The project, itself, is the result of relationships.

Did you have times of more intense involvement in the project than at other times?

The period of my most intensive work lasted about five years, from 1998 to 2003. I went to every ball.

How’d you get started in photography?

I took a photo class when I was a freshman. I attended Queensborough Community College for the first three years I went to school. I didn’t go full time. And Jules Allen was one of my professors there; I worked as his assistant. By the third photo class, I’d been bitten by the photo bug. I went to study at Hunter College. One of the main reasons I went to Hunter was because Roy DeCarava was there, and I wanted to study with him. He taught independent study, and only on Wednesdays. Because he had a lot of authority and power, he could just teach one day. I made sure that I took the class right before or right after lunch, so I could have more time with him, go to lunch with him and talk. (He always ate at this one Italian restaurant.) And we’d talk about his struggles as an African American artist, or difficulties he was having with a show. I started this project as a class project. That’s what you had to do, work on a project and show him pictures every week. He’d critique them and all that.

Who are your major influences as an artist?

Well, early on, Jules Allen. But later, I gravitated toward Roy DeCarava and Stanley Greene’s work. I met Stanley through working with Jules. From Stanley I learned about quietness in photographs. He’s a really outgoing, fun-loving guy, but his photographs are about quietness. And they have a certain romantic feel to them. When we first met he was photographing Paris at night. One of his early books, Somnambule, hugely influenced me because it had these quiet, romantic qualities. That book influenced my visions. If you marry quietness with carnival, you have Gerard Gaskin.

Do you think of yourself as a documentary artist? How do you describe yourself within the photographic tradition? How do you make a living?

I’d say I’m a “documentary fine art photographer.” Right now, I freelance. I shoot for magazines, record companies. I shoot events and advertisements.

You’ve been working on this project for twenty years. And you keep working on it. Why?

That’s a good question. How to answer. . . . Do you watch cricket? Ultimately, I wanted this to be a book. That was always my goal. So I continued on.

Why do you think of the book as the ultimate vehicle for presenting this work?

Part of the reason is training. When I was being trained as a photographer, I was taught that a book is the culmination of any long-term endeavor, to really complete the project. I also love photography books. I love to just sit and look at pictures, to look at book covers over and over again. I believe thata good book is a book that you want to return to. I always wanted to see my images in book format.

What was your reaction when you learned that Deborah Willis had picked your work to win the CDS/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography?

I was working as a part-time waiter when the phone rang. I saw the call was from Durham, but I couldn’t take the call at work. After the shift ended, I listened to the message, and it was Alexa Dilworth at the Center for Documentary Studies asking me to give her a call. I went home that night and told my wife, Nimanthi, that I thought I had won. It was too late to call you back, and I remember not being able to sleep that night. The next morning, I got up and went to visit my mother, who was in hospital with cancer. When I reached you and you told me I had won, I started to cry like a baby. I just started to think about my life and how hard I had worked to make this happen. I also thought about how my mother, who had supported me for so many years. She died three days after I found out that I won. Thinking about winning the award brings up mixed emotions for me because of how difficult things were at the time.

About new beginnings . . . are you working on a new body of work?

Yes, I am working on three projects. One is a portrait project on Trinidadian artists; the second, is about West Indian identity and its relationship to the game of cricket. I draw from some of the arguments C. L. R. James makes in his book Beyond a Boundary about the relationship between the rise of anticolonial nationalism in the West Indies and cricket. The third project is one I have been thinking about as I prepare to move to Syracuse, New York. My wife begins teaching at Colgate University this fall, and during my visits to Syracuse and the upstate area, I was struck by the starkness, and the aesthetic possibilities, of upstate post-industrial cities. So I hope to capture the landscape and urban life of Syracuse, very much inspired by thephotographs W. Eugene Smith took in Pittsburgh.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025