James Friedman on Gratitude

This week Lenscratch is on vacation and I have asked a variety of photographers from across the country to fill in for me. James Friedman shares several wonderful posts from his blog, about his early days as a photographer. Jim has a new website, and it’s worth spending time with his wide variety of image making. Two of his projects, Pleasures and Terrors of Kissing, and Interior Design were featured on Lenscratch in June.

by James Friedman

Gratitude Part 1 August 6, 2010

Recently, I was thinking how fortunate I was to have studied with Minor White at MIT, one of five students in the experimental graduate program he developed, Toward A Whole Photography. After reviewing my application and a portfolio of 35mm copy transparencies of my photographs, Minor requested I travel to Cambridge for an interview and to see my original prints. It was in April 1972 that I first met Minor, in his office in the Creative Photography Program’s facility; it was housed above DuPont Gymnasium, where later I would spend considerable time playing basketball before and after classes (no, Minor never played basketball with us, though we invited him). When I walked into Minor’s office for my interview, I discovered him on the floor napping. I didn’t want to disturb him, so I said his name softly and he quickly rose from the floor, smiling. His long white hair began to glow as it interrupted the sunlight flooding in on that spring afternoon.

The interview lasted two and a half hours as we discussed the program, my portfolio and contemporary photography. He told me to expect a letter inviting me to participate in the program, scheduled to begin in September. As I was leaving, Minor asked what my astrological sign was. Only later did I learn that astrology would be central to my graduate studies at MIT. Still, it seems odd that an institution like MIT would include as part of the curriculum individual meetings with Minor’s astrologer. The “reading” of our astrological charts was to provide useful insights into our creative process. My session lasted more than three hours—and to this day, when I’m in need of creative inspiration, I refer to the notes I took during that meeting.

from Minor White, January 31, 1975

As a teacher, Minor dealt with each student in radically different ways. In providing feedback about photographs, he was kind and supportive with some students while he responded to others with highly negative and incisive criticism. Sensing that each student required a unique response, he was able to assess his or her needs swiftly and, for the most part, with accuracy. For me, it was helpful though, at times, dispiriting, for him destroy some of my photographs and throw them in the trashcan next to his desk. Intuitively, he knew I needed someone to challenge me in provocative ways. His strategies forced me to make decisions about how I wanted my photographs to affect an audience.

I think about Minor every day. I left Toward A Whole Photography radically changed and certain I would devote my life to being a photographer.

Gratitude Part 2 August 15, 2010

Because Minor White’s Toward A Whole Photography at MIT was a one-year graduate program that offered no degree, at its conclusion I decided to pursue a master’s degree. In the autumn of 1973, I was admitted to the graduate program in photography at San Francisco State University. During a seminar in my first semester there, the idea of inviting some of the Bay Area’s prominent photographers to our class came up. Our first choice was Imogen Cunningham, then 90 years old, who was enjoying long over due recognition and still active as a photographer. I was chosen to call and ask her to participate in our seminar, but in speaking with her, Imogen declined, explaining that her assistant had just quit and she was overwhelmed with work. Without much thought, I blurted, “I’ll be your assistant.” She said she’d think about it. After sharing the bad news with my classmates that she had declined our invitation, I forgot about my conversation with Imogen. Several weeks later and much to my surprise, I got a phone call from Imogen. She asked when I could begin working for her; “Immediately,” I replied. Apparently, she had checked me out by speaking with her longtime colleagues and good friends Minor White and Jack Welpott; Jack was chair of San Francisco State’s photography program and one of my professors.

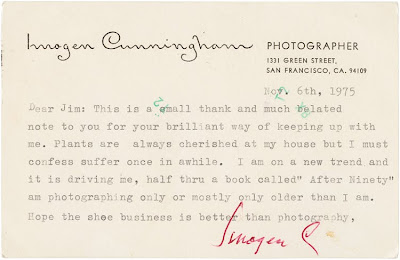

from Imogen Cunningham, November 6, 1975

Sunday, October 28, 1973 entry from my journal:

Friday (10/26), I began working for Imogen. When I arrived at her house, she greeted me with, “I want you to put my past in order. I have to get ready to die…my father was 98 [when he died] and my mother was 88. How old was your father [when he died?].” I replied, “He was 48.” (Even now, I have no idea how she knew my father had died.) “Oh, he was young. Well, you haven’t got long, have you? It all depends on your father. We’d better get started.”

“Do you know Brett Weston? No? Well, don’t bother…Edward Weston was unlike what you’ve read about him—he was arrogant—he wrote me a letter, saying he was going to be great! The person who taught him to see was Margarethe Mather. Nobody knows that but she taught him to see. I knew his wife and five mistresses. Margarethe was the best. She and his first wife saw him off to Mexico together, when he went to be with another mistress, Tina Modotti.”

From 1907-1909, Imogen had been one of Edward Curtis’ assistants in Seattle. On the floor near the entrance to her workroom, she had a beautiful, unframed photograph of an American Indian in a canoe Curtis had signed in pen. There was also a portrait of her shown in profile with her hand under her chin, done by Curtis. She said that Curtis had given her the original negative and when she was reprocessing it last year (1972), she immersed it in water and the emulsion separated from the glass plate and floated away.

Imogen’s house, really a cottage, shows a life devoted to photography—at this point about 75 years. There are photos everywhere—original Edward Weston works and there is a 4” x 5”, exquisite print of Imogen’s “Triangles” in the bathroom. On her bookshelves are many out-of-print books such as Edward and Charis Weston’s The Cats of Wildcat Hill—Imogen said her portrait of Edward Weston with all of the cats was taken when he had Parkinson’s Disease—“you could tell by his hands.”

Edward Weston, Photographer, with His Cats, 1945 by Imogen Cunningham

Imogen’s idea of my putting her “past in order” was to have me organize her correspondence, which she intended to donate to the Smithsonian Institution. I spent many hours in the cellar under her house in a room adjacent to the darkroom, reading her letters and personal notes. The darkroom was a rustic redwood room that had a homemade sink, ancient Leitz and Ellwood enlargers and, among many other chemicals, a bottle of Rodinal film developer at least thirty years old that she still used.

Most of Imogen’s letters, starting in the 1920s, had been typed with carbon copies. As I organized the correspondence, I read letters exchanged between her and photographers such as Ansel Adams and Minor White. In several letters Minor discussed his growing interest in eastern philosophy and Zen studies, and her responses to them seemed to be teasing him or somewhat skeptical.

Eventually, because of the growing interest in exhibiting, publishing and purchasing Imogen’s photographs, my duties turned away from organizing her correspondence to spotting (retouching) prints and mounting and preparing work for shipping. I took her grocery shopping and ran errands with her, as well as taking in the occasional photography exhibit.

Imogen was charming, generous, funny, unassuming and self-deprecating. But she was also highly opinionated and spoke at times with disappointment and bitterness that it took so long for her to achieve the prominence she deserved. I remember her saying, “They think I’m so great now…where were they years ago?” Since her death—on the very same day as Minor White’s passing, June 24, 1976—Imogen’s eminence as one of modernist photography’s most celebrated and influential practitioners has grown explosively. It has been a wonderful postscript to her remarkable life.

Imogen was an important link to artists like Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams. She was able to thrive in a medium dominated by men. She was a model for how to live an enduring, productive life. Imogen was indefatigable: she was 87 when she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and photographed until the end (her work from 1976 has been published), dying at 93. After working for Imogen, my commitment to photography was complete.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025