Ann Mitchell on The Still Life

This week I am on vacation and a variety of photographers from around the country are contributing to Lenscratch. Los Angeles photographer, educator, and good friend, Ann Mitchell, wanted to reflect on her appreciation of still life imagery. Much of Ann’s own exquisite imagery is captured with a large format camera, and surely the slowed-down nature of working this way makes her appreciate the time it takes to create the perfect composition.

By Ann Mitchell

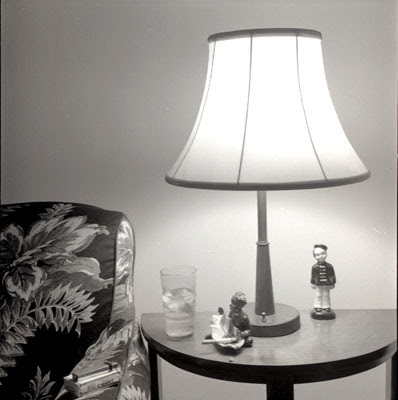

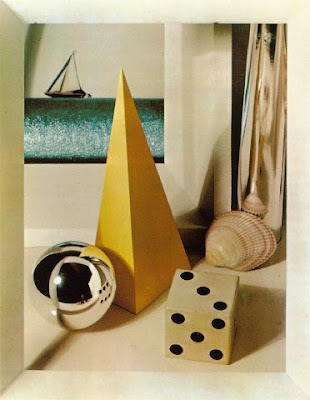

I’ve always had a real love for still-life photography – it’s this incredibly difficult and lonely thing – creating an entire world out of the nothingness of a studio is not for the faint of heart. Just like large format, it requires mad photo skills. You’ve got to master lighting, working with props and composition, and it’s all got to be in service to a concept.

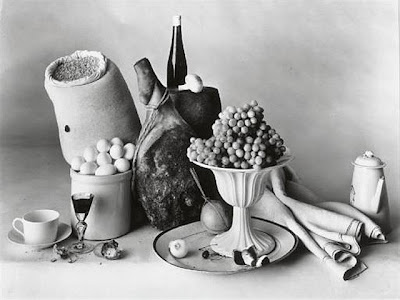

For the most part, even early 20th Century masters such as Paul Outerbridge worked as commercial photographers long before their work was discovered by the art world. I first saw his work in the early 1980’s at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery. Hawkins had recently purchased a large portion of the Outerbridge estate and had started to promote the work. Outerbridge brought his love of Modernism to advertising photography and was an early adopter of color photography – back when you had to create your own color.

I want to thank Aline for this opportunity. It gave me a chance to think about an area of photography that I loved for many years, but haven’t practiced since the 90’s. Still-life is part production design, part social anthropology, by it’s very nature it allows the artist an opportunity to comment on their world and what’s important to them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Wishmaker and The Landau GalleryFebruary 27th, 2024

-

Interview with Kate Greene: Photographing What Is UnseenFebruary 20th, 2024