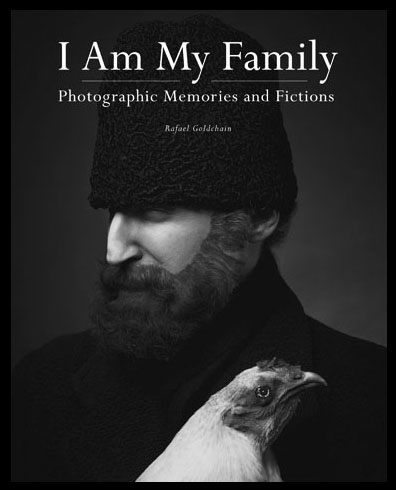

Rafael Goldchain: I Am My Family

I discovered Rafael Goldchain’s wonderful self-portraits in a recent Lenswork Magazine. Rafael is a Chilean-Canadian Jewish artist, who was born in Santiago de Chile, lived in Jerusalem in the early 1970s, and moved to Canada in the late 1970s. He has created an amazing series of photographs bases on memories, family and fiction, which was published in 2008 by Princeton Architectural Press.

Rafael received a MFA from York University and a Bachelor of Applied Arts from Ryerson University, both in Toronto. He has garnered numerous awards including the Duke and Duchess of York Prize in Photography from The Canada Council for the Arts. His photographs have been exhibited across Canada, Chile, the United States, Cuba, Germany, Italy, the Czech Republic, and Mexico. His work is featured in many private and public collections including the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in Ottawa, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Portland Art Museum, and the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego. Goldchain is currently Professor and Program Coordinator of the Bachelor of Applied Arts – Photography at Sheridan Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning in Oakville, Ontario, Canada.

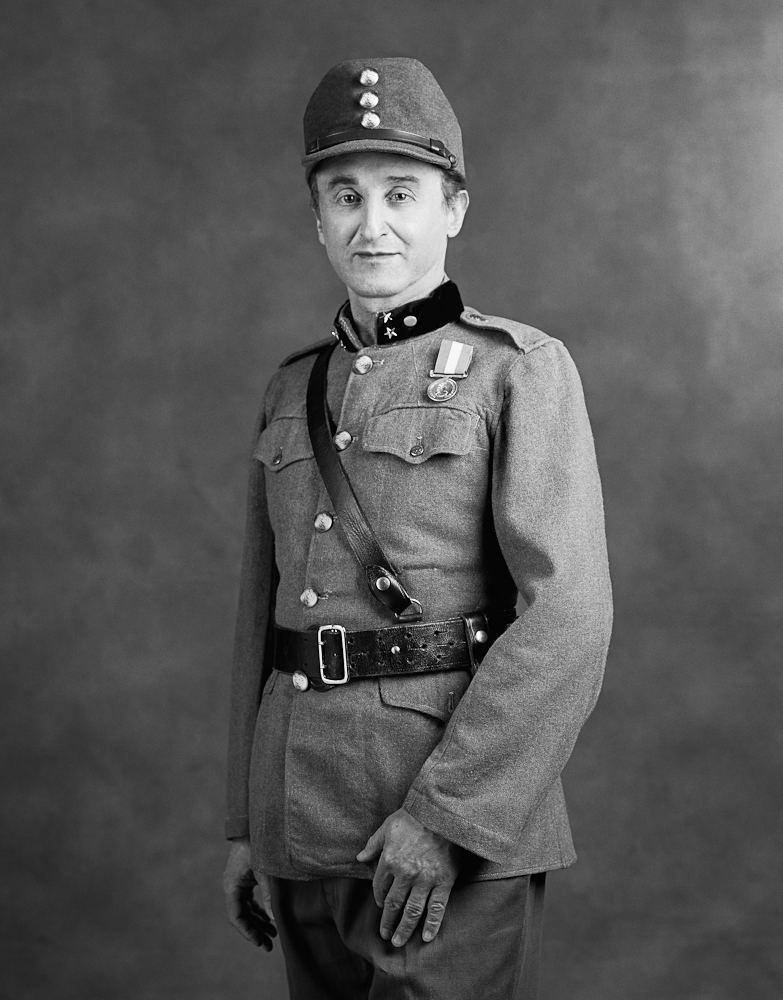

Motl Yosef Goldszajn Liberman

d. Santiago de Chile, 1959

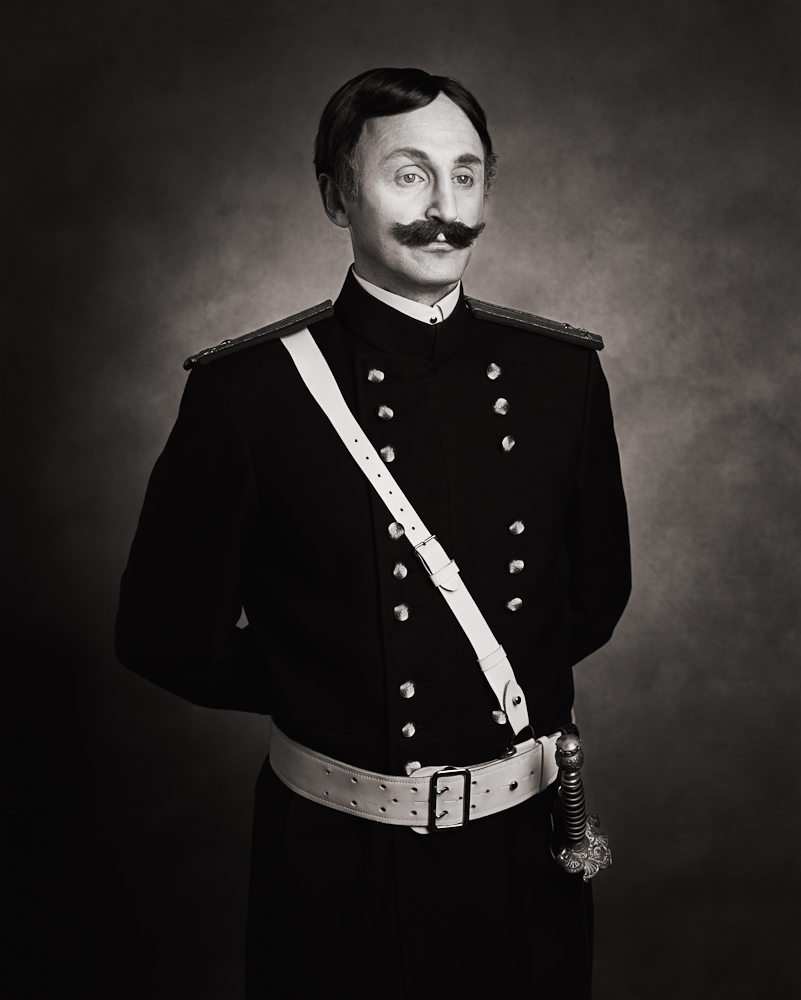

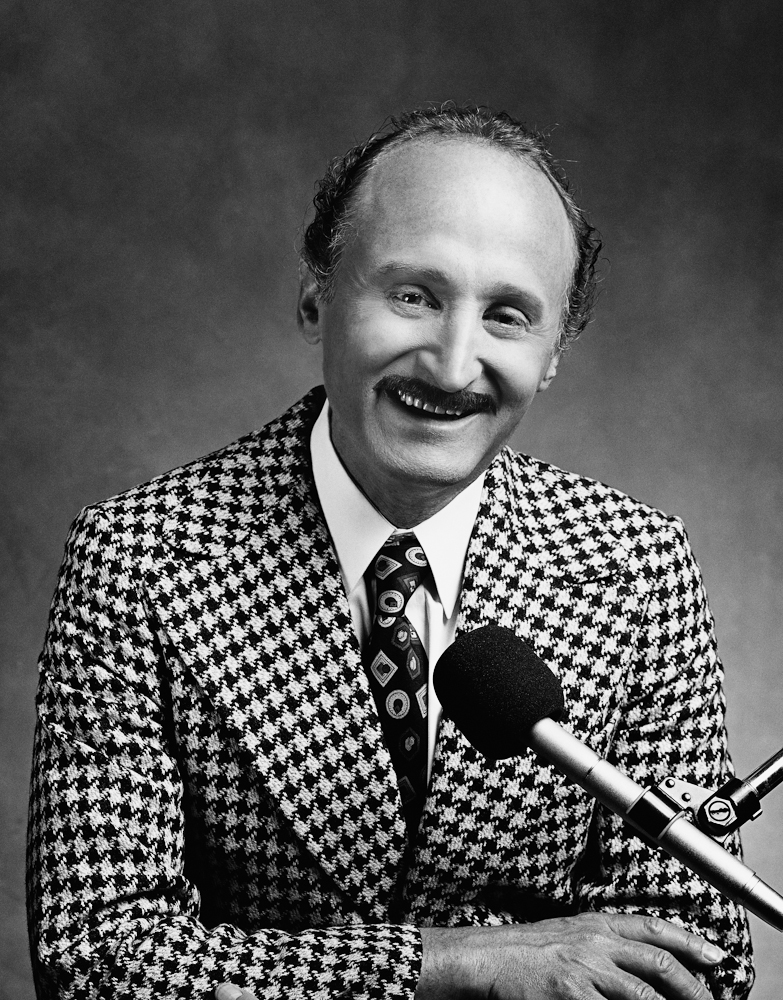

The self-portraits in I Am My Family are detailed reenactments of ancestral figures that can be thought of as acts of “naming” linked to mourning and remembrance. I Am My Family proposes a language of mourning through self-portraiture and through the conventions of family portrait photography. In reenacting ancestors through a relationship of genetic resemblance, and through the conventions of the portrait photograph, the self-portraits in I Am My Family suggest that we look at family photographs in order to recognize ourselves in the photographic trace left by the ancestral other.

I Am My Family is the product of a process that started several years ago when my son was born. I slowly realized that my role as parent included the responsibility to pass on to my son a familial and cultural inheritance, and that such inheritance would need to be gathered and delivered gradually in a manner appropriate to his age. My attempts at historical story-telling, cultural and familial, public and private, made me acutely aware of how much I knew of the former, and how little of the latter. I thought of the many erasures that family history is subject to, and of the way in which my South American and Jewish educations privileged public histories. As I reached my middle years it became important to not only retrieve basic historical facts such as family names, dates, and genealogical relations, but also to reach towards the world of my ancestors as a basic foundation of an identity that I could pass on to my son. While I could access the considerable existing stores of knowledge of Eastern European Jewish life, knowledge of the pre-Holocaust lives of my grandparents and their families only exists in fragments deeply buried within the memories of elderly relatives.

I Am My Family explores the relations amongst family portraiture, mourning and remembrance, notions of history, memory, and of justice and inheritance. Just as I am the carrier of memories and ancestral history fragments through whom the familial past is brought up into the present (for my son to carry into the future), the self-portraits in I Am My Family visually articulate a process of identity representation through which ancestral figures take on my likeness as they become visible (while at the same time remaining concealed behind my features and behind the conventions of the portrait photograph) to serve as a reminder of the unavoidable work of inheritance. These images are the result of a reconstructive process that acknowledges its own limitations in that the construction of an image of the past unavoidably involves a mixture of fragmented memory, artifice, and invention, and that this mixture necessarily evolves as it is transmitted from generation to generation.

d. Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1974

d. Poland, early 1940’s

d. Krasnik, Poland, late 1800’s

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026