Brian Adams: The States Project: Alaska

Alaska Guest Editor Ben Huff shares the work of Brian Adams

I first became aware of Brian Adams when I was living in Fairbanks, as he was a talented young editorial photographer. I often found myself living vicariously through his photos from small corners of the state. His Disappearing Villages pictures are the ones that made me an admirer of his ambition. He brings a timely perspective to the endangered coastal communities of the West and North of the state that is at once both poignant and lyrical. Although Brian and I have chatted by email over the years, regrettably, he is the one photographer featured whom I haven’t yet met in person – which made our following conversation even more enlightening…

I first became aware of Brian Adams when I was living in Fairbanks, as he was a talented young editorial photographer. I often found myself living vicariously through his photos from small corners of the state. His Disappearing Villages pictures are the ones that made me an admirer of his ambition. He brings a timely perspective to the endangered coastal communities of the West and North of the state that is at once both poignant and lyrical. Although Brian and I have chatted by email over the years, regrettably, he is the one photographer featured whom I haven’t yet met in person – which made our following conversation even more enlightening…

Brian Adams is an editorial and commercial photographer based in Anchorage, Alaska specializing in environmental portraiture and medium-format photography. His work has been featured in both national and international publications, and his work documenting Native Alaskan villages has been showcased in galleries across the United States. His first book of photography, I AM ALASKAN, was published in October 2013 by University Of Alaska Press, and he has exhibited the work at the Alaska Native Arts Foundation in Anchorage and LA Artcore in Los Angeles.

How has being from Alaska shaped you photographically?

Being here has shaped me the way that I think being from a lot of small towns shapes people artistically–we connect with the community around us and aren’t as fearful of approaching people we don’t know and especially who may be from different cultures. I feel like being from here has given me huge advantages photographically in the professional sense–I was able to grab opportunities that would have been harder to get in front of in a larger city. And, my heritage is deep here, and so because my family is from one of the northern Alaska Native villages, I’ve always had distant cousins and relatives supporting me and looking out for me when traveling and working on those projects.

In a more abstract sense, I think being from a place that’s far away from other places has made me into a grounded person and artist. I just want to make photos, and I’ve never strayed from that simple objective.

You’re a successful commercial photographer, and last year had your first book I Am Alaskan published. Your Disappearing Villages work, which make up the middle set or pictures, stands out as your most personal of the collection. What separates those pictures from the others for you?

Disappearing Villages is incredibly personal for me. Visiting villages feels like a homecoming of sorts; even though I didn’t grow up in the villages myself, I feel a sense of culture there that is hard to describe. I feel rooted there and that the people are my people, and so the Disappearing Villages project is also one of the first projects that I felt ethically compelled to cover as one of the Inupiat. The pace of life there is also slower, and it feels natural to spend quite a lot of time just observing before pressing the shutter. Situations that allow for this quiet kind of observation is how I photograph best.

Being a photographer who was born in Alaska, do you feel a sense of responsibility to get it right?

Yes. Absolutely. I want to make images that represent this place that I love. There is quite a lot of work out there that claims to represent “real Alaskans” or a “real Alaska” that is really just so commercial that to me it feels like it does anything but. Or so much work that I feel could be good if the photographer actually spent more than a day or two photographing before heading back out again. I want to make images that show what the light is like here, what the people are like and what’s important to them. I want to tell a story with my lifetime’s work of documenting this place–the story of how this beautiful, remote, strange American place shapes the people who live here and vice versa.

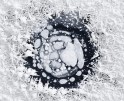

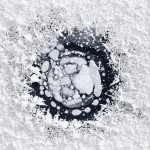

Disappearing Villages speaks to both the coastal erosion, as well as a possible cultural erosion. How has this work evolved for you over time?

Over time, the cultural issues have become more personal and central to this project. What started as a project focused on the land evolved into a focus on the people. The people of the North are very much dependent on their land for survival–both physical survival and cultural. But now there are televisions in homes and the Internet, and running water at the schools. There are chips and processed foods in the stores. The suicide rates are high in the villages, as are the domestic violence and sexual assault rates. These seem to all be related to the much larger postcolonial discussion that is difficult to tell in pictures. The Inupiat were originally nomadic until colonization, so the idea that the cultures are connected to these specific places–not the land and the sea at large–and need to rebuild villages elsewhere is kind of new. There has already been one very painful erosion, if you will, that Alaska Native people are charged with recovering from. Now, many are facing additional drastic and difficult changes ahead of them. I want to continue to tell this story–that they are here, that their culture is alive and thriving and that they have persevered and survived.

Is it a project that you’re still working on? And has the focus narrowed down, or broadened, over time?

Yes, I am still working on it. It has broadened in some ways and narrowed in others. I am looking to find smaller stories within stories while also continuing to document a rapidly changing landscape.

Your wife, Ash, is also a photographer, and you have children. How does family influence your work here?

My wife Ash is and always has been an inspiration to me. Her background is in photojournalism, so while she works as a commercial photographer as well, her foundation is in story-telling. I think she’d say we inspire each other. We look at work together every day, every night. We talk and breathe photography and story. She moved here because she loved the sky here. Even that is inspiring to me.

My son and daughter have taught me something about the preciousness of life. I feel that I connect with people on a deeper level since their births, and I see that reflected in my portraits. And they push me in a way I didn’t expect. I think about leaving them a legacy now, about making work that is timeless in quality but documents this time, this moment.

Do you feel that having a photographic community is important? What is your impression of the community in Alaska?

Yes, I think it’s very important. I hate saying this, as I love Alaska with all my heart, and I do have some close photo friends here, my wife included, that have made up my little personal community, but I honestly wish the photographic community in Alaska, on the whole, was a more supportive community. The photographic communities I’ve been able to connect with outside of the state seem to maintain perspective on photography in the global big-world sense. Photographers elsewhere–the top players in the field, even–know that good work always rises. That there is no rushing the process of becoming a good photographer. That we are all where we are at. And we are all perfect in that regard and can all just keep working and getting better. But put a bunch of commercial photographers in a small town all vying for the same jobs, and I guess it’s easy for some people to forget that we all have the best jobs in the world. And that good work should always be celebrated by all of us. (It’s my hope that the Alaska photo community gels in this way during my lifetime).

Do you ever have dreams of living somewhere else?

Of course. But never in the sense of leaving Alaska permanently. My wife and I have talked about buying a condo in New York or LA and kind of being bi-coastal for the sake of editorial work and projects outside of Alaska, but we never want to be uprooted from Alaska. This is our home, and we want to make a lifetime of images in this place.

What’s next? Anything new on the horizon that you can share with us?

I’m actually working a lot on the Disappearing Villages project this year, so I’ll be up North and around the coasts quite a bit. My wife and I are working together on a kind of storytelling cookbook with Alaskan chef Rob Kinneen–telling stories of local producers and weaving in beautiful food and recipes by Rob. And there, of course, are so many penciled projects that I’m hoping to make more solidified over the next year.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015