Pamela Pecchio: The States Project: Virginia

Pamela Pecchio was one of the first to welcome me to Virginia by inviting me to the University of Virginia for a discussion with Thomas Struth. Pamela moves seamlessly between the domestic space and the landscape, as can be seen in her series Habitation and On Longing, Distance and Heavy Metal. Her latest series, Inheritance, brings domestic space and landscape together within the same photograph while also critiquing the written and visual gendered history of our state and nation. Pamela is the recipient of many awards and is internationally exhibited. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Virginia.

Pamela Pecchio received her MFA in Photography from Yale University in 2001, where she was awarded the Richard Dixon Welling Prize. She has exhibited across the US and in China and Europe. Her New York exhibitions have been reviewed in the New Yorker and the Village Voice. She is the author of two books, eight, an artist’s book published by Nexus Press, and 509, a limited edition monograph published by Daniel 13 Press. Permanent collections include the Yale University Art Museum, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. Pecchio is represented by Daniel Cooney Fine Art Gallery in New York and is currently Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Virginia.

Inheritance

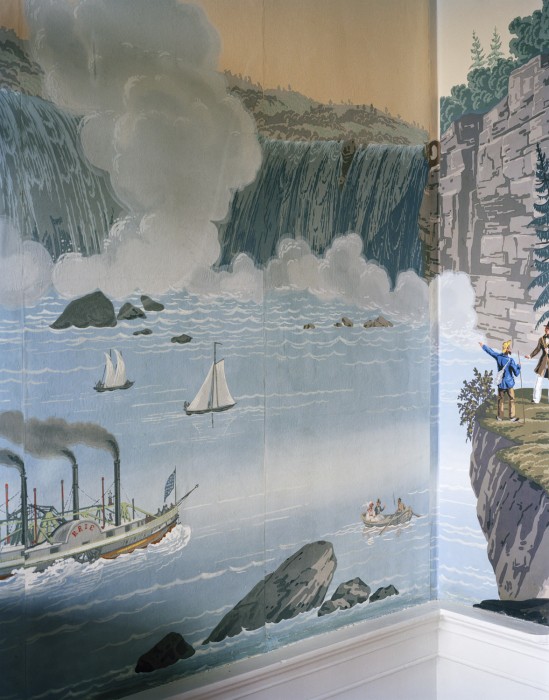

My photographs focus on domestic landscapes of the United States. My practice is both aesthetic and critical. I not only create art objects, but I also use photography to observe and interpret relationships between people and the places they live.

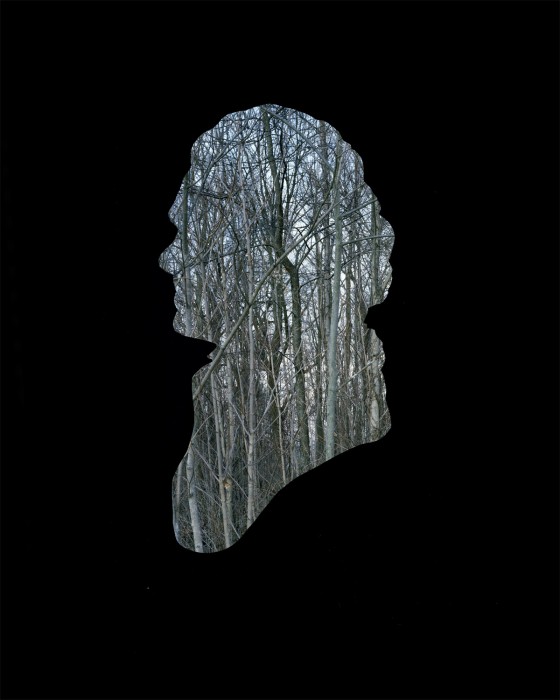

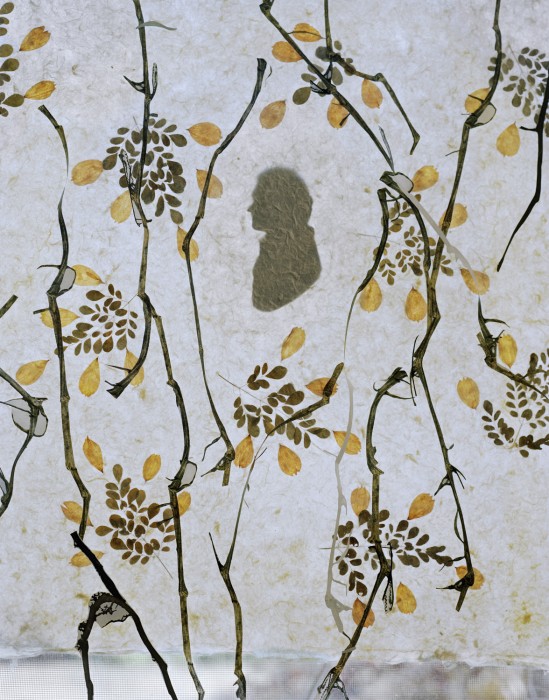

My current work, Inheritance, addresses the intersection of personal history with national history as I have begun to experience it in Charlottesville, Virginia. As a female professor at Thomas Jefferson’s University, I am responding to the traces of our “founding fathers” that mark the university and the local landscape, a distinctly masculine geography of national formation. As with my previous work, this project views domestic interiors and the landscape as visual details fraught with both history and personal narrative.

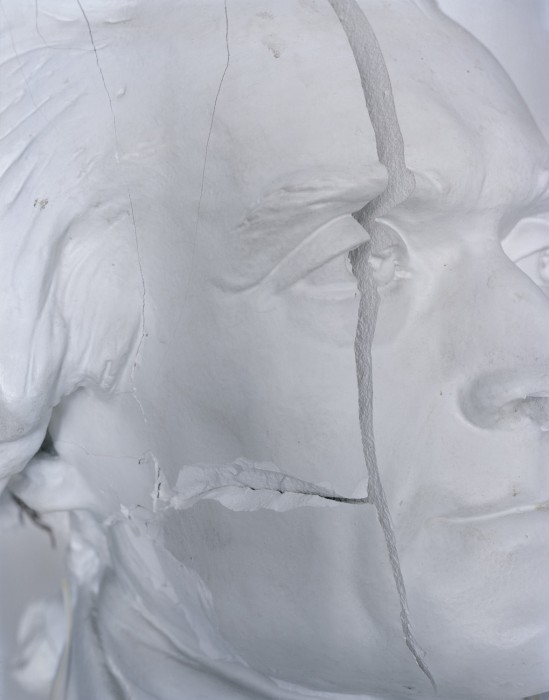

I am particularly interested in the use of the parental term father to describe the founders. A parent serves as a caretaker, a provider, and a guide. Many scholars of early American history remind us of the less conspicuous yet vitally important contributions of the founding mothers. In the work, I include visual elements of both the masculine and feminine to create connections and tensions between these binary roles, and to remind viewers of the role of the founding mothers. My intention is not to critique the founding fathers, but instead to comment on the ways Americans interpret their authority and their memory. The goal is to detach them from their pedestals and the weight of history and, in some way, take care of them.

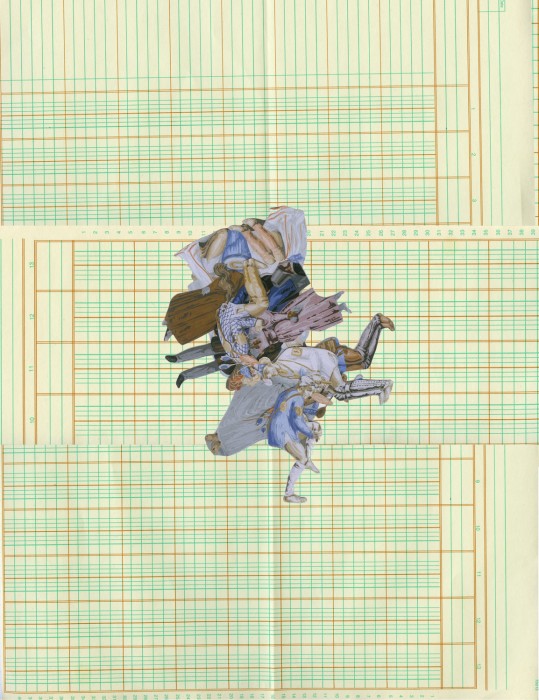

Inheritance includes both still-life constructions that I find and those that I create in my studio or home. The found works are in places of geographic significance to the founding fathers, near their homes and other important landmarks. The collaged materials include renderings of the founding fathers, paper representations of vegetation, and detritus from my home. The domestic remnants include scraps from my artistic work, as well as detritus from my domestic role as mother and caretaker. I have chosen collage specifically to create a conceptual parallel between collaging materials in art-making and collaging public and private stories to write history.

I’m interested in your use of different forms of paper throughout this series to construct the integrated histories. It seems at times you want to draw attention to its use through the cut-out or by leaving the white voids between root strands or branches. I’m curious if you have any specific intentions behind the use of paper as a primary material to be photographed?

Yes and no. I’ve always been interested in how photography takes the three-dimensional world and creates a new, abstracted two-dimensional object. I took vegetation from the world, scanned it, printed it, cut it and installed it in a new three-dimensional space to then be rephotographed. I do want it to be understood as artificial and a reproduction. It’s not the thing itself, but a re-creation, and a new thing.

Paper was a natural material for this process, and the process speaks to the tools of traditional “women’s work.” In addition to photography, I spend a lot of time with craft. I quilt, knit, sew and make books by hand. I’ve been looking for a way to integrate these seemingly disparate parts of my practice for many years.

History has been traditionally passed on through the written word, most often inscribed by the elite, or through oral narratives. Women and many cultural groups were often marginalized and their stories falsified to meet the desires of the men in power. Do you think the age of the Internet changes the way history is written down now and the way it will be understood in the future?

Oh, absolutely. I don’t know how it couldn’t. I do think it is a bit overwhelming, though. How do we know where to look? It’s hard to filter the information, and the anonymity of the internet allows people to be cruel without shame.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 3rd, 2024

-

Jordan Eagles in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 2nd, 2024

-

Interview with Peah Guilmoth: The Search for Beauty and EscapeFebruary 23rd, 2024

-

In Conversation with Cig Harvey: Beauty, Books, and InstallationFebruary 21st, 2024