Susan Worsham: The States Project: Virginia

Susan Worsham is contagiously passionate about everything around her and embodies all that comes to mind when considering a Virginia photographer. Her work is rooted in her storied history growing up in Virginia and dealing with some particularly difficult situations. Her photographs are full of life and beauty, a perfect mirror of who she is as a person. I first met Susan virtually when I asked her to Skype into one of my Southern Studies photography classes at the University of South Carolina. She was pretty nervous because she hadn’t done a talk before, but she was incredible. She brought some of my students to tears, and they continued to talk about her and her work for the rest of the semester. We met in person a few months later in the Mississippi Delta for a collaborative photography project and have been close friends ever since. Her photographs speak for themselves and have been acknowledged through numerous grants and exhibitions. Make sure to check out the audio piece as well to get an additional glimpse into her work with Margaret.

Susan Worsham was born in Richmond Virginia. She took her first photography class while studying graphic design in college. In 2009 Susan was nominated for the Santa Fe Prize For Photography, and her book, Some Fox Trails In Virginia, won first runner up in the fine art category of the Blurb Photography Book Now International Competition. In 2011, she was named one of Photo District News 30 Emerging Photographers to watch, and her work was chosen to represent the United States in The Lishui 14th International Photography Festival In China. Named one of Oxford American’s “New Superstars of Southern Art,” she has been an artist-in-residence at Light Work in Syracuse, New York, where her work was published in Contact Sheet 168: Bittersweet/Bloodwork. Her photographs are held in private collections and have been exhibited at the New York Photo Festival, The Australian Centre for Photography, The Photographic Center Northwest, and the Danville Museum in Virginia. Her solo shows include Candela Books + Gallery in Richmond, Virginia; Light Work in Syracuse, New York; and The Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans.

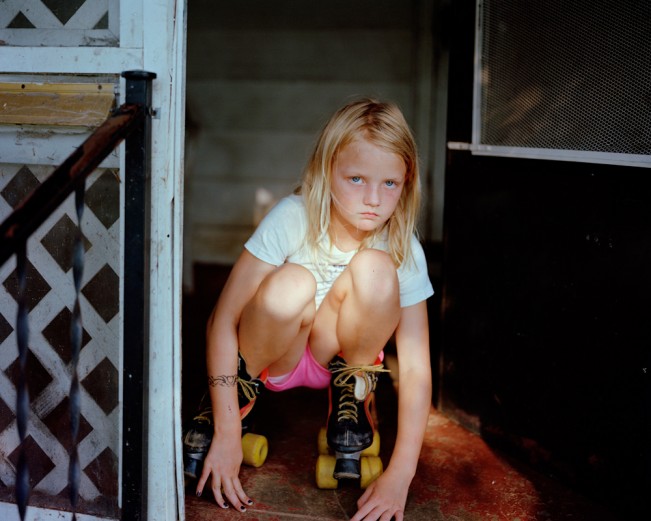

Bittersweet On Bostwick Lane

In this body of work I am coming to terms with loss. I have lost both my father and my mother, yet it’s the suicide of my brother that seeps into my work like a slow forming stain, and has become a stand in for the others. My brother took his own life on his first visit home after severing his spinal cord in a motorcycle accident. What always comes to mind are the first few lines of his suicide note.

“I arrived home just about the time the honeysuckle blooms”.

Russell was not the sort of person to notice flowers, so I find it really beautiful, and achingly sad at how poetic it was for him to stop and see the beauty around him if only because he knew it would be for the last time.

The last person to see my brother alive was my oldest neighbor, Margaret Daniel. It’s fitting that she has now become my subject and the strongest thread throughout my work. The first time we sat together to make a portrait, she told me the story of Russell’s last day.

” I made your brother my home made bread, his favorite… I buttered a slice and took it up to him, and he called down, Margaret can I have some more of that bread? He finished the whole loaf, and then me and your mother went for a walk down the lane, and when we came back he had shot himself.”

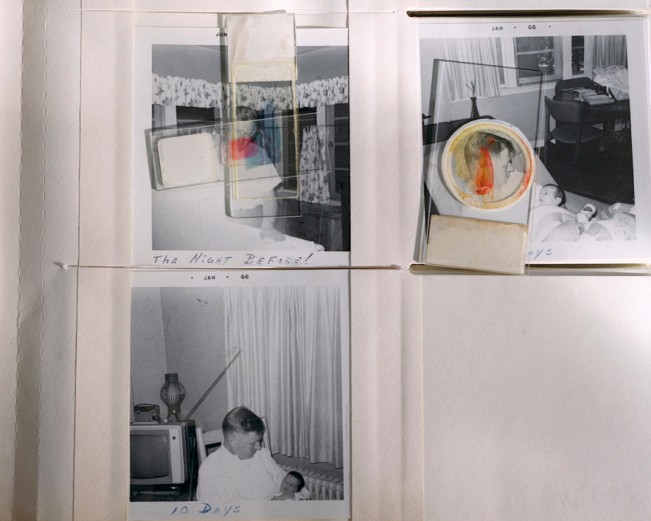

Margaret gracefully weaves stories of buttering my brother’s last slice of bread with memories of me as a young girl, wanting to eat her homemade strawberry jelly on my new white bedspread. She laughs as she recalls finding me with fruit all over the bed. Blood and jelly, two very different stains. I thread these stories together, of pain and loss and of the sweetness of childhood memories.

My memories become intertwined with hers as I rediscover my past through her stories. Together, we’ve created a family album of what was once the intangible landscape of my childhood. The work encircles itself as our conversations about native flowers, life and death become the seeds of my photographs. Each time I visit Margaret I enter through the kitchen door, and each time she has a new story to tell which enriches my work like a complex broth. The kitchen and the yard are where we do our fieldwork, as we pick fruit and remove the rotten parts to make a more palatable jelly. This process has become a sort of poetry for me, as I document her showing me how to strain the last remnants of sweetness and color from crabapples, using bandages to catch the pink-stained juice.

Audio piece with Margaret discussing Birney Imes Honey

Your work in Virginia is so poignant and personal, how do you find similar inspirations when you work outside of the state?

I am very fortunate that wherever I am, I can find inspiration, or at least a curiosity that eventually leads me to something. Quite often that something special finds me.

I remember as a visiting artist at Light Work in Syracuse, New York I met what most people including herself would call a crazy cat lady. She introduced herself to me as I was photographing a deserted van. When she pointed towards her house, I realized that I had been focusing my attention and my camera in the wrong direction. Her house stood in the middle of what she told me was a concrete factory. She would not sell the home that she grew up in, so they just built around her. Her house had the weight of around 80 pigeons on its roof and a layer of concrete dust covered everything and filled the air whenever a car passed by.

She told me about the peach, plum and cherry trees that once populated her childhood home. As we stood hunched over in the arched back of the attic, she pointed at the phantom trees through the window. Concrete trucks, slabs, and dust held the place where fruit trees and gardens once stood. I remember her showing me photos of herself and her sister as children standing in front of a large Peony bush in that same yard.

It is like Syracuse had given me my own Margaret Daniel to visit while I was there.

Conversationally, you talk a lot about cross-pollination in terms of your process; can you tell us a little about that?

When I think of pollination or cross pollination, I think of a residue that you pick up and in turn bring with you like a stain. It is like what I said about carrying home with you. You also carry a residue like bees would carry pollen.

Everything that I’ve seen, everyone that I’ve met, and all of the photographer’s work that has inspired me, leaves a residue, a sort of stain on my eye.

When I was first starting to make work in the Mississippi Delta I visited with the photographer Birney Imes. I had heard that he kept bees and made his own honey. I brought with me a gift of the crabapple jelly that Margaret and I had made together from the Virginia Trees. As we rode around in a little golf buggy on his farm.

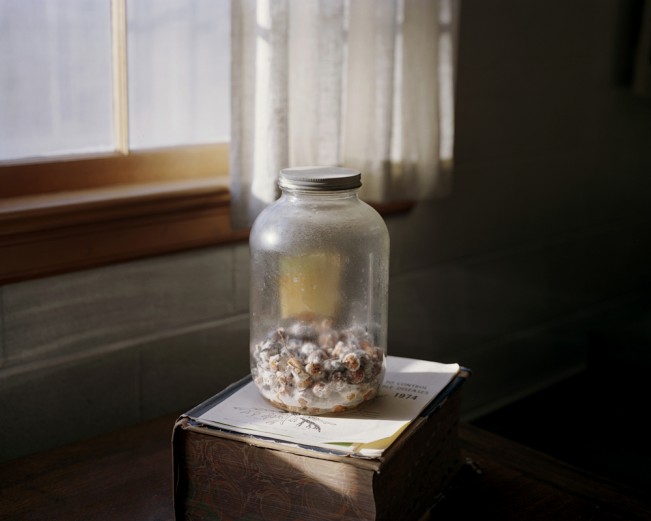

We talked about my neighbor Margaret, his persimmon trees, and grafting, where you take one tree that produces beautiful fruit, and join it to another prized for strong roots. At home in Virginia, my neighbor and I had just talked about grafting. I was finding inspiration in a new place and could not wait to come back to photograph his trees. I left with a jar of honey made from Mississippi bees packed tight in my suitcase, although I opened it a few times to share with people that I stopped to photograph in the Delta.

Birney wrote that he had enjoyed Margaret’s jelly on Cathead Biscuits, and I sent audio of Margaret and I enjoying his honey on her smaller homemade biscuits, as she told me stories of her own family’s kept bees. I started to mix Mississippi with Virginia, a sort of cross-pollination as I photographed his honey in her basement.

This perhaps is a better answer to your first question.

Your work is very much about the experience of loss. Those experiences and emotions come through beautifully in your photographs. What do you feel you have gained from making this work?

I do not think it is even possible to put into words all that I have gained. It’s too big. It is kind of like death and loss. In a sense, I have created my own sort of language through microscopic slides, photographs, collected audio conversations and even poetry to talk about something that big. I have learned many ways to talk about the same thing.

I am still learning. I feel like I am discovering/unraveling something, and the thread keeps coming and coming, like a never ending thread of inspiration. I think the more you work you begin to discover that thread once invisible to you that connects all of the work that you make. I have learned to keep myself open to my creative process, and to never think that I know exactly what the work is about. To keep it elastic so that it changes and grows with me as I make it.

More than anything this artistic process has been a healing process. Although I’ve lost family, I have also gained family and a dear friend in Margaret. Margaret inspires my creativity and sparks my curiosity daily. In one of our recorded conversations, she picks up a dead branch from a walnut tree and shows me the fungus growing in clusters across its surface. Oh and by the way… she does this in a very excited manner.

“ Look what it’s doing, it’s eating it up, taking it back to nature. It’s a mold, look at it, see what it does, it’s a wood rotter, it rots the wood and takes it back to nature.”

So that fungus and the Black Walnut tree have a symbiotic relationship. The fungus takes away the fallen dead wood and uses it as nourishment which in turn, enriches the soil. Margaret continues to show me all of the wonders of the world in my own backyard. There is loss in the landscape, but also change and growth.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 3rd, 2024

-

Jordan Eagles in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 2nd, 2024

-

Interview with Peah Guilmoth: The Search for Beauty and EscapeFebruary 23rd, 2024

-

In Conversation with Cig Harvey: Beauty, Books, and InstallationFebruary 21st, 2024