Sarah Christianson: When the Landscape is Quiet Again: North Dakota’s Oil Boom

©Sarah Christianson, Flaring near the Blue Buttes, January 2015, from the series “When the Landscape is Quiet Again: North Dakota’s Oil Boom”

Photographer Sarah Christianson has a lot to celebrate. Selected for the 2015 Award for Women Documentarians for the inaugural Archive of Documentary Arts Collection Awards, which resulted in the acquisition of 30 c-prints from When the Landscape is Quiet Again by the Archive of Documentary Arts at Duke University. She will also open an exhibition of the same body of work at the Fargo Public Library (Main Library, 102 3rd St North, Fargo, ND) on September 14th – October 31st, with an Artist Lecture on Thursday, September 17, 7pm. Her work is currently part of the Group Exhibition in Chicago, Field Study, at the David Weinberg Photography Gallery running from August 7 – October 3, 2015, curated for the 7th Annual Filter Photo Festival.

©Sarah Christianson, Pipeline through Brenda & Richard Jorgenson’s land, May 2013, from the series “When the Landscape is Quiet Again: North Dakota’s Oil Boom”

Sarah grew up on a four-generation family farm in the heart of eastern North Dakota’s Red River Valley (an hour north of Fargo). Immersed in that vast expanse of the Great Plains, she developed a strong affinity for its landscape. This deep-rooted connection to place has had a profound effect on her photographic work: despite moving to San Francisco in 2009, she continues to document the subtleties and nuances of the Midwestern landscape and experience through long-term projects.

She earned an MFA in photography from the University of Minnesota. Her work has been exhibited internationally and featured by Mother Jones, High Country News, and PDN. Sarah has received project grants from the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Center for Cultural Innovation. Her first book, Homeplace (Daylight Books), documents the history and uncertain future of her family’s farm by interweaving her images with old snapshots and documents culled from her personal archive. Sarah is currently working on projects that examine the effects of North Dakota’s boom-and-bust cycles on its western communities and environment. Throughout her work, she uses her personal experiences and connection to the land to evoke a strong sense of place, history, and time.

©Sarah Christianson, Drilling rig near Little Missouri National Grasslands, May 2013, from the series “When the Landscape is Quiet Again: North Dakota’s Oil Boom”

“We do not want to halt progress. We do not plan to be selfish and say ‘North Dakota will not share its energy resource.’ No, we simply want to insure the most efficient and environmentally sound method of utilizing our precious resources for the benefit of the broadest number of people possible.

And when we are through with that and the landscape is quiet again…let those who follow and repopulate the land be able to say, our grandparents did their job well. The land is as good and in some cases better than before.” -North Dakota Governor Art Link, October 11, 1973

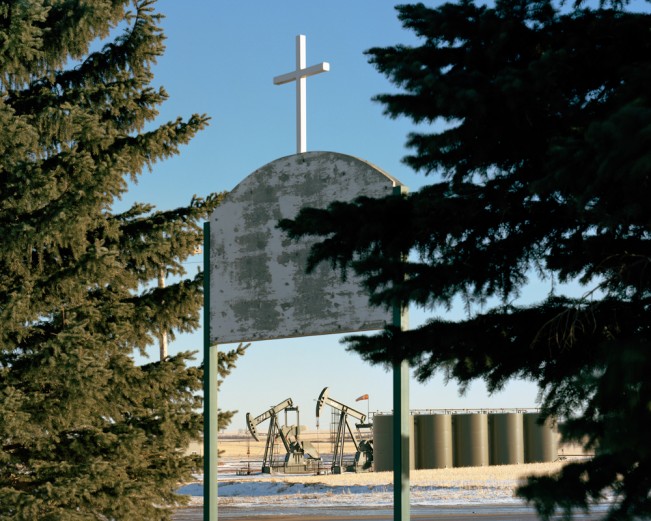

Since 2012, I have been documenting the legacy of oil booms and busts in my home state and how the region is changing again today, thanks to horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. My photographs bear witness to the transformation of western North Dakota’s quiet agrarian landscape into an industrial zone dotted with well sites, criss-crossed by pipelines, lit up by natural gas flares, and contaminated by oil and toxic saltwater spills. The oil fields are currently pumping out over a million barrels per day from 10,000 active wells, and companies are planning to drill thousands more.

©Sarah Christianson, Corn field, Bottineau County, September 2013 “Caution: Hazardous chemicals may be present in this area. Failure to use caution may cause serious injury or illness!

These activities have brought a steady stream of revenue, people, and jobs to this economically depressed region. Everyone wants a piece of the action, including my family: since the start of the boom we have been profiting by leasing mineral rights on land my great-grandparents homesteaded near Watford City. Although many other families are doing the same, I am still torn: what are the hidden costs of this oil boom? What happened to Governor Link’s ideas of responsible resource extraction and land stewardship? What can North Dakota’s two prior boom-and-bust cycles teach us about building a better future?

Experts anticipated that the Bakken Boom would continue for several decades, but falling oil prices may trigger another bust. Meanwhile, its effects are still rippling across the country in the wake of massive spills and oil train explosions. By examining the scars from previous booms and the new wounds being inflicted upon my home, I urge viewers to contemplate the lessons of the past and to fight for the quality of life they deserve when the landscape is quiet again.

©Sarah Christianson, One million gallons of saltwater spilled, Ft. Berthold Reservation, July 2014 This toxic wastewater flowed downhill over two miles to Bear Den Bay, part of Lake Sakakawea, leaving a swath of dead trees & vegetation in its wake. Officials do not believe the contamination reached the tribe’s freshwater intake from the lake, but many residents in the area are skeptical of their claims.

When the Landscape is Quiet Again was first exhibited at SF Camerawork in 2014. Since its premiere, the work has been praised by reviews in Mother Jones and Art Practical. “Christianson’s photos have a strong, careful, quiet presence to them. A lot of the beauty in a place like the Plains is exceptionally subtle. These photos capture that stillness that just washes over you and juxtaposes it with the scarring interruption of drilling operations” (Mark Murrmann, Mother Jones, 6 February 2014). “No single photograph in [Christianson’s exhibit] gets one’s blood boiling. Her images of her home state…elicit a slow-burning experience of rage. Rather than focusing on obvious signs of destruction, Christianson’s photographs collectively emphasize the insidiousness of the waste and danger that are often hiding in plain sight” (Larissa Archer, Art Practical, March 19, 2014).

This project was funded by an Individual Artist Commission grant of the San Francisco Arts Commission and an Investing in Artists grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation. Additional support was provided by RayKo Photo Center and in-the-field assistance was given by the Dakota Resource Council, the Killdeer Mountain Alliance, the Northwest Landowners Association, and numerous other individuals.

©Sarah Christianson, Barley from Artz’s saltwater-damaged field, September 2013 These samples of barley were collected on the same day, from the immediate area of the spill site (left) and from a more distant, unaffected patch of the field (right). The stunted growth of the heads on the left indicate that the saltwater spill had been going on for several weeks without detection. Saltwater is an industry byproduct that can be up to 30 times saltier than the ocean. It burns the land, making healthy agricultural production impossible.

©Sarah Christianson, ECO-Pad well site on my family’s mineral acres, Watford City, ND My maternal great-grandparents homesteaded near Watford in 1912. Although their farm was sold in the 1960s, my family retained the mineral rights on the land. They have a share in 7 wells, with more on the way.

©Sarah Christianson, Natural gas flaring at my family’s wells, Watford City, ND It’s estimated that 100 million cubic feet of natural gas is flared off per well each day.

©Sarah Christianson, Killdeer Mountains, July 2014 This area is many things: a traditional hunting ground, a sacred Native American site for ceremony and prayer, a Civil War era battlefield where Dakota and Lakota families were massacred. It’s also a place threatened by the development of mineral resources.

©Sarah Christianson, The Badlands south of Medora, July 2014 Aging infrastructure from the two prior boom-and-bust cycles can still be found across the state.

©Sarah Christianson, Well site carved out of bluffs near the Badlands, August 2013 The Lakota called this area “mako sica” or “land bad.” French-Canadian fur trappers did the same, claiming these were “bad lands to travel through” because of the rugged terrain. Although no drilling is taking place in Teddy Roosevelt National Park, the noises and sight of oil development along its borders are clear.

©Sarah Christianson, LK-Wing Wells, near Killdeer Mountains, August 2013 The oil industry is trying to minimize environmental impacts by building larger pads with multiple wells on them, versus a scattering of individual pads for individual wells. These six Hess Corp. wells are on a pad adjacent to the Killdeer Mountains Wildlife Management Area, a haven for deer, elk, bighorn sheep, pheasant, grouse, wild turkey, and antelope

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026