Thomas Michael Alleman: The Unwinding

Thomas Alleman has created a number of significant projects about what’s outside the front door–his focus on the ubiquitous American Apparel billboards made us consider the placement of these visual scars; his long-term project, Sunshine and Noir, finds black and white beauty on the streets of cities around the world; Dancing the Dragon’s Jaw explores the 1980’s AID’s crisis in San Francisco–all of these series well seen by someone who began his career as a newspaper photographer.

Today we go back to his beginnings as a photographer with a personal, powerful and poignant project, The Unwinding, that shows a family in decline at which Thomas had a ringside seat. This series garnered a place in the Top 50 in Critical Mass this year, and in my opinion, it is well deserved.

Thomas Alleman was born and raised in Detroit, where his father was a traveling salesman, and his mother was a ceramic artist. He graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in English Literature.

During a fifteen-year newspaper career, Tom was a frequent winner of distinctions from the National Press Photographer’s Association, as well as being named California Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1995 and Los Angeles Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1996.

As a magazine freelancer, Tom’s pictures have been regularly published in Time, People, Business Week, Barrons, Smithsonian, and National Geographic Traveler, and have also appeared in US News & World Report, Brandweek, Sunset, Harper’s, and Travel Holiday. Tom has shot covers for Chief Executive, People, Priority, Acoustic Guitar, Private Clubs, Time for Kids, Diverse, and Library Journal.

Tom exhibited Social Studies, a series of street photographs, widely in Southern California. Sunshine & Noir, a book-length collection of black-and-white urban landscapes made in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, had it’s solo debut at the Afterimage Gallery in Dallas in April 2006. Subsequent solo exhibitions include: the Robin Rice Gallery in New York in November 2008 and March 2013; the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR in October 2009; the Xianshwan Photo Festival in Inner Mongolia, China, in 2010; California State University at Chico in 2011; and the Duncan Miller Gallery in Los Angeles, February 2013. Fifty-three of Tom’s photographs of gay San Francisco, shot between 1985 and 1988, debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December 2012, under the title, Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. Tom’s photographs of Inner Mongolia were recently on display at the Blue Sky Gallery.

The Unwinding

In the years after an indifferent college career, I waited tables and taught myself photography by practicing on my friends and family. I carried my Minolta and a 28mm lens back home to Detroit for holidays and occasional weekends.

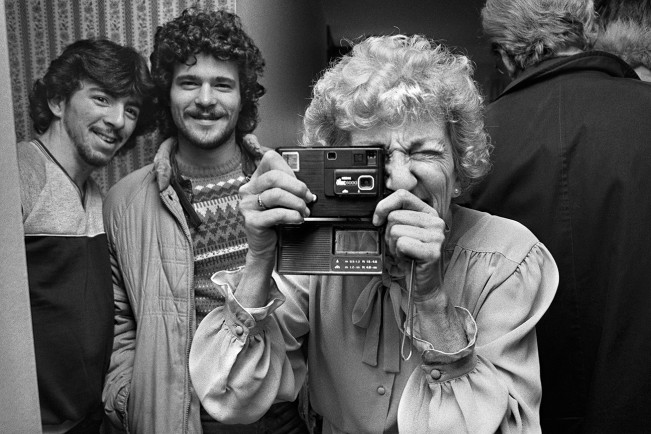

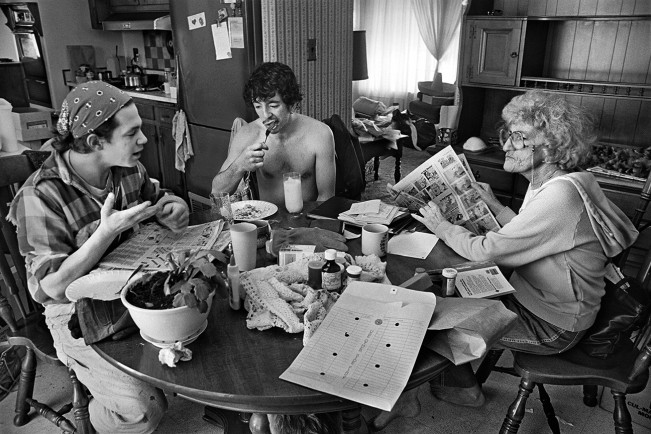

The pictures I made of my family had an immediate frisson for me, a wallop way beyond the surprise success of their exposure or the virtues of their composition. After years away from the house on Newport Street, I returned with a heightened awareness of the layers of subtext in every situation, and I snapped away at it from every angle, and some of my images hinted at the ghosts and passions running beneath the everyday household dramas I beheld.

I began practicing my pictures of my mother and the family in 1982, just as their downward trajectory began slowly but certainly spiraling. In a few short years in the mid-70s, my father’s career had fizzled out, and he’d developed diabetes and had bypass surgery; he spent the 80’s pacing the house each day, waiting for his heart to explode. My youngest brother, still in high school, was already an alcoholic; our middle brother was restless and angry, and inclined to operatic denunciations of us all, apropos of nothing. My mother’s lungs were a cinder, from 40 years of smoking, and she gasped for breath. And I was, in that battered company, some version of a “golden child”: the first born, the fruit of their best hopes, the one who got away before it all went to shit. (A hundred miles away, where I languished in my college town, I worked in a Mexican restaurant and painted houses for my rent, but they never got to witness any of that, and they had no interest in knowing I was small and irrelevant when I wasn’t in the family orbit.) So I stood before them while they writhed and withered, shouting at each other, limping through worn-out rooms, and I made photographs for my own edification, and they let me.

Why did they let me? They may have wanted me to “tell their story”, as reporters usually believe; maybe their agony had some measure of performance in it, and they hoped that I could judge and validate their histrionic complaints about one another; or maybe they thought, somehow, I could save them. But there was certainly a layer of weird theater playing out, in any case: if another wide-angle camera were somehow affixed to a high corner of the kitchen, or hidden behind a bookcase in the living room, it would have shown me there, too, part of the scene, the one studying and sketching those hapless players: arrogant, omniscient, blessed by luck. That’s the scene at it’s most fucked-up, and it hovers beyond the edges of these pictures. But they allowed all that without a word, and I carried on for eight years.

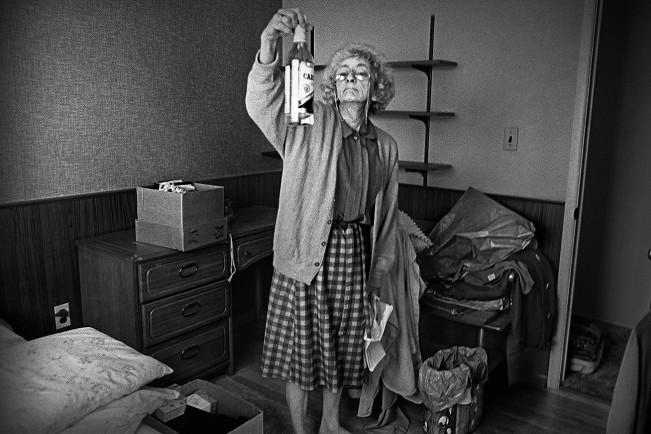

Of course, it separated me from them, and I knew that after a while. But I couldn’t think of a better way to survive those dreary years, to be with them but not of them. Over time, both my confidence and my ambivalence grew, each fed by my “mastery” of that “material”. I felt a wobbly kind of shame, and wondered it I’d betrayed them all.

As it became clearer that my mother’s final months were near—she spent half of her final year in emergency rooms and ICUs, breathless, frail and afraid—I was forced to confront two obvious futures: I could stay the course and “finish my work” as she died, and I’d have a complicated and intimate book to show for my long “travail”. Or, I could cease and desist my grim project, forget the whole damned thing, and join her in her final season as a son and companion, and experience her death as nakedly as possible, and send her off with a kind of dignity. I’m sorry to admit, the decision wasn’t easy, or quickly made. But I decided, after all, to stop making pictures of her on New Year’s Eve, 1990, while she rested uneasily in a room in the Pulmonary Ward at Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina.

She died the following July, a few days after her 63rd birthday. I’d been at her beside for a month, and she seemed to have recovered from the crisis that had brought me there. I’d just returned home to Los Angeles when my brother called with the news, and I flew back to Asheville the next day.

I put my negatives in a banker’s box, where they stayed for twenty years, following me from apartment to apartment to house and garage, until now.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026