Edward Burtynsky: Water

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Xiaolangdi Dam #1, Yellow River, Henan Province, China, 2011 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

The Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, opened a massive exhibition, Edward Burtynsky: Water, including more than 60 large-scale color photographs that form a global portrait of the intricate intersections of humanity and our most precious natural resource. The exhibition, organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art, will run through May 15.

“Edward Burtynsky harnesses the advances in digital photography to create high-tech images reminiscent of the modern masters that he so admires, artists such as Jean Dubuffet, David Shapiro, Casper David Friedrich, and Richard Diebenkorn,” said Chrysler Museum Director Erik Neil. “Just as those painters had an affinity for landscapes, Burtynsky explores abstract art with aerial photographs that minimize detail and context to create massive images that defy description.”

Burtynsky uses recent technological changes in photography to create massive images, several feet tall and wide. “His photos engulf the viewer with stunning vistas in incredible detail. These images—part photograph, part abstraction, and part anthropological treatise—transform the viewers’ experience and challenge their senses to comprehend what is shown in the frame”.

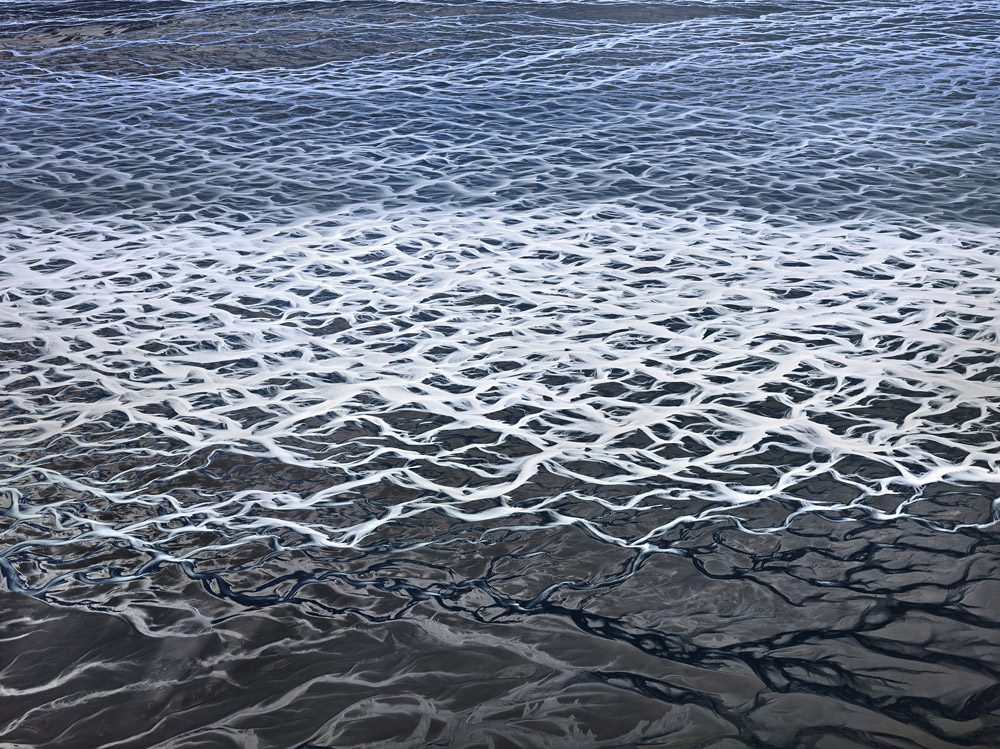

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Ölfusá River #1, Iceland, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 60 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Edward Burtynsky was born in 1955 in St. Catharines, Ontario, and is one of Canada’s most respected photographers. He has long been recognized for his ability to combine vast and serious subject matter with a rigorous, formal approach to picture-making. The results are images that are part abstraction, part architecture, and part raw data. His photographs are included in the collections of more than 60 major museums around the world, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California. He received his Bachelor of Applied Arts in photography/media studies from Ryerson University in 1982. In 1985, he founded Toronto Image Works, a photography lab and training center for Toronto’s art community. Burtynsky’s photographic development was influenced by the sites and images of the General Motors plant in his hometown and eventually led to his exploration of the human systems we have imposed on our natural landscape. He has been awarded the TED Prize, The Outreach Award at the Rencontres d’Arles, the Roloff Beny Book Award, and the Rogers Best Canadian Film Award.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Navajo Reservation / Suburb, Phoenix, Arizona, USA, 2011 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Photographer Edward Burtynsky shares the story behind his gravity defying imagery:

“I’ve absolutely liberated myself of where I get to stand. If I want to be anywhere, I will be there, I will find a way to be there. It’s quite interesting when you kind of release yourself from gravity, so to speak, and find that you can make the point of view anywhere that you want it to be.”

“I’m not really a landscape photographer, per se. I’m a photographer of human systems that are imposed upon a landscape.”

The exhibition includes 58 photographs, all large (4 by 5 feet minimum), all extremely high-definition, and all composed with great skill. Many are aerial photographs, as his quest to rise above the ordinary translated into the use of planes, helicopters, drones, and even a 50-foot pneumatic mast.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Step-well #4, Sar Kund Baori, Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 2010 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

“I work backwards from the subject matter to the point of view, and in this project, for the first time, completely released myself from gravity, that the point of view would be wherever it is. And that was interesting, so it was very much a global approach to the idea of water, with no restrictions as to where I could stand. … That for me was a very interesting creative jump.”

The exhibition focuses on six themes, including agriculture, aquaculture, waterfront, and control. In the theme distress, scenes of great beauty are mixed with an unsettling sense that something just isn’t right. For the theme source, for the first time in three decades, he was taking pictures of pristine wilderness.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Rice Terraces #2, Western Yunnan Province, China, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

“Human ingenuity and the development of its industries have allowed us to control the Earth’s water in ways that were unimaginable even just a century ago. While trying to accommodate the growing needs of an expanding, and very thirsty civilization, we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways. In this new and powerful role over the planet, we are also capable of engineering our own demise. We have to learn to think more long-term about the consequences of what we are doing, while we are doing it. My hope is that these pictures will stimulate a process of thinking about something essential to our survival, something we often take for granted—until it’s gone.”

“Water is not optional. As a liquid, it’s the ultimate thing that provides for life. If it’s missing, humans have to leave that area. It’s as simple as that.”

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) VeronaWalk, Naples, Florida, USA, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Pivot Irrigation / Suburb, South of Yuma, Arizona, USA, 2011 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Water

I began to think about water as a subject for my work in 2007, while on a production tour photographing gold mines in Australia—the first continent in this era to begin drying up. Stories about farmers leaving as their land dehydrated were everywhere in the news.

While there I met a photojournalist who recounted a story about an incident he had experienced in a bar in Adelaide. He ordered a beer and a glass of water, finished his beer, paid the bill and was about to leave when the bartender stopped him and instructed him to finish his glass of water. Suddenly water took on a new meaning for me. I realized water, unlike oil, is not optional. Without it we perish. I thought about ways that I could build a body of work around the idea of water. Unlike my Oil and China projects, with Water I had no preconceived notions about what the images in such a project might look like. I trusted that my intuition would lead me to the pictures.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Kumbh Mela #1, Haridwar, India, 2010 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

In 2008 my research started in earnest. I wanted to find ways to make compelling photographs about the human systems employed to redirect and control water. I soon realized that views from ground level could not show the enormous scale of activity. I had to get up high, into the air, to see it from a bird’s-eye perspective. Determined by the specifics of each location, I would find a way to depict the most telling viewpoints. The ensuing four years found me at work in nine countries: employing location crews, using man-lifts, small fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters (both remote and piloted) and a specially designed fifty-foot pneumatic mast with camera mount and fibre-optic remote. This pulling away from the earth has allowed me to see our world in ways once unavailable to artists. In addition, the evolution of high-quality digital camera equipment has allowed me to create crisp, finely detailed images from moving aircraft—something that could not be easily accomplished with older, analogue film systems.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Dryland Farming #2, Monegros County, Aragon, Spain, 2010 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, Baja, Mexico, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 60 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Markarfljót River #1, Erosion Control, Iceland, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 60 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

As production on the Water project began to roll out I categorized the images into: distress, control, agriculture, aquaculture, waterfront, and finally source. Distress included landscapes such as the Colorado River Delta, that has not seen a drop of water from that river in over forty years, and is now a desert; or Owens Lake, that saw its water diverted to Los Angeles in 1913 and is now a dry toxic lakebed. Agriculture represents – by far – the largest human activity upon the planet. Approximately seventy percent of all freshwater under our control is dedicated to this activity. I went to China and Spain to see the process of farming fish and seafood. The section Aquaculture provides a glimpse into a quickly growing and increasingly important food source. Waterfront looks at the way we shape land to create manufactured waterfront properties, and speaks to me about the human need and desire to be near water—even if it is artificial. I went to India to witness the largest pilgrimage on the planet with thirty-five million people arriving on the holiest day to bathe in the Ganges and release them of their sins – an ancient spiritual belief in the cleansing power and sacredness of water. Source comes from my journey to those places where a critical stage in the hydrological cycle takes place; in the mountains, containing glaciers and pure fresh snow. I went to northern British Columbia and Iceland to capture these images. They are the first landscapes in over thirty years I have taken that focus specifically on pristine wilderness, instead of the imposition of human systems upon it.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Glacial Runoff #1, Skeidararsandur, Iceland, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 60 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

I feel this project encompasses some of the most poetic and abstract work of my career. I was seven years old when I discovered my love of making art, while painting landscapes alongside my father who painted as a hobby. I loved the tubes of oil paint and the smell of the linseed oil and the names of their colours: burnt umber, chromium blue, cadmium red. When I was eleven I got my first camera and a complete darkroom. I immediately fell in love with photography and never looked back. However, I never lost my love for painting and have tipped my hat to it a number of times throughout my work. While executing the Water project, I was pleased to see images emerging that referenced some of my favourite painters, including: Caspar David Friedrich, Jean Dubuffet, David Shapiro and Richard Diebenkorn. The aerial perspective that I adopted for this project, as well as its subject matter, allowed those influences to seep into my photographs.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Dryland Farming #24, Monegros County, Aragon, Spain, 2010 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Over the past five years I have learned a few things about water. When disrupted from its natural course there are always winners and losers. The moment water cannot find its own way back to the ocean or be absorbed by the ground, we are changing the landscape. When a stream or river is diverted, all life downstream is affected and remains altered until water returns. Insects, plants, frogs, the salamanders and countless other creatures, including people, have paid an enormous price because of our voracious appetite for water—and what we do to the earth while getting at it.

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Greenhouses, Almira Peninsula, Spain, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Human ingenuity and the development of its industries have allowed us to control the Earth’s water in ways that were unimaginable even just a century ago. While trying to accommodate the growing needs of an expanding, and very thirsty civilization, we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways. In this new and powerful role over the planet, we are also capable of engineering our own demise. We have to learn to think more long-term about the consequences of what we are doing, while we are doing it. My hope is that these pictures will stimulate a process of thinking about something essential to our survival, something we often take for granted—until it’s gone —Edward Burtynsky

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Marine Aquaculture #1, Luoyuan Bay, Fujian Province, China, 2012 Digital chromogenic print, 60 x 80 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Edward Burtynsky (Canadian, b. 1955) Benidorm #2, Spain, 2010 Digital chromogenic print, 48 x 64 inches © Edward Burtynsky All images courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026