Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: California

Combining his love of history with compassion for others, Kevin Kunishi’s work examines the lasting human impact of United States foreign policy. His break-out project, Los Restos de la Revolución took viewers on an intimate journey through Nicaraguan highland forests and into the homes of those affected by the decade’s long revolution. His current project shared for our LENSCRATCH California photographer feature provides an unflinching look at the United States colonization of Hawaii and the lasting cultural impact on native islanders. Kevin has received significant recognition for this project and is often asked by tourist photographers for the location of significant cultural spots such as burial grounds, to whom he advises a trip into town in order ask the largest native Hawaiian they can find.

Kevin Kunishi (born in Oakland, CA) is a photographic artist living in the San Francisco Bay area. His photographic practice is primarily rooted in aftermath and identity.

His work has been recognized by numerous organizations and publications including The New Yorker, The Sunday Telegraph, VICE, Le Monde, Mother Jones, American Photo Magazine, The Huffington Post, The International Photography Awards, Le Journal de la Photographie, AI-AP, The New York Photo Festival, Bloomberg Businessweek, Fast Company, Esquire, VISSLA, The Surfers Journal, Monocle, L’imparfaite, Allegra, ONWARD, Photo District News, CENTER, Photolucida, CMYK Magazine, Photographer’s Forum and Prix de la Photographie, Paris (PX3).

His work has been shown nationally at Project Basho in Philadelphia, PA; The Honolulu Museum of Art, Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, CA; The Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography; V1 Gallery, Copenhagen, Denmark; Black & Blue Gallery, Brooklyn, New York; Interurban Gallery, Vancouver, Canada; The Hashtag Gallery, Toronto, Canada; Galerie Nowhere, Montreal, Canada; The Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C.; The Daylight Project Space in Hillsborough, NC; and The Bekman Gallery in New York.

In 2011, he was the honorary recipient of the Blue Earth Alliance Award for Best Photography Project, an award that honors projects that demonstrate excellence in the field of photography.

His first monograph Los Restos de la Revolución was released in the Fall of 2012 by Daylight Publishing, was selected as one of Photo-Eye’s Best Books of 2012 and selected as one of PDN’s-2012 Indie Photo Books of The Year.

“Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.” – Thoreau

My ancestors arrived on the windward shores of the island of Hawaii in the late 1800’s. They headed north from Hilo to labor in the sugarcane fields above the cliffs of the Hamakua coast.

I began making photographs there in the summer of 2011 after an obligatory return to sort through family interests.

Once a sovereign nation, unilaterally annexed by the United States in 1898, Hawaii bears the markings of Western assimilation. Just beneath the surface, the physical features, social constructs, and the emotional milieu of the islands and its peoples are palpable.

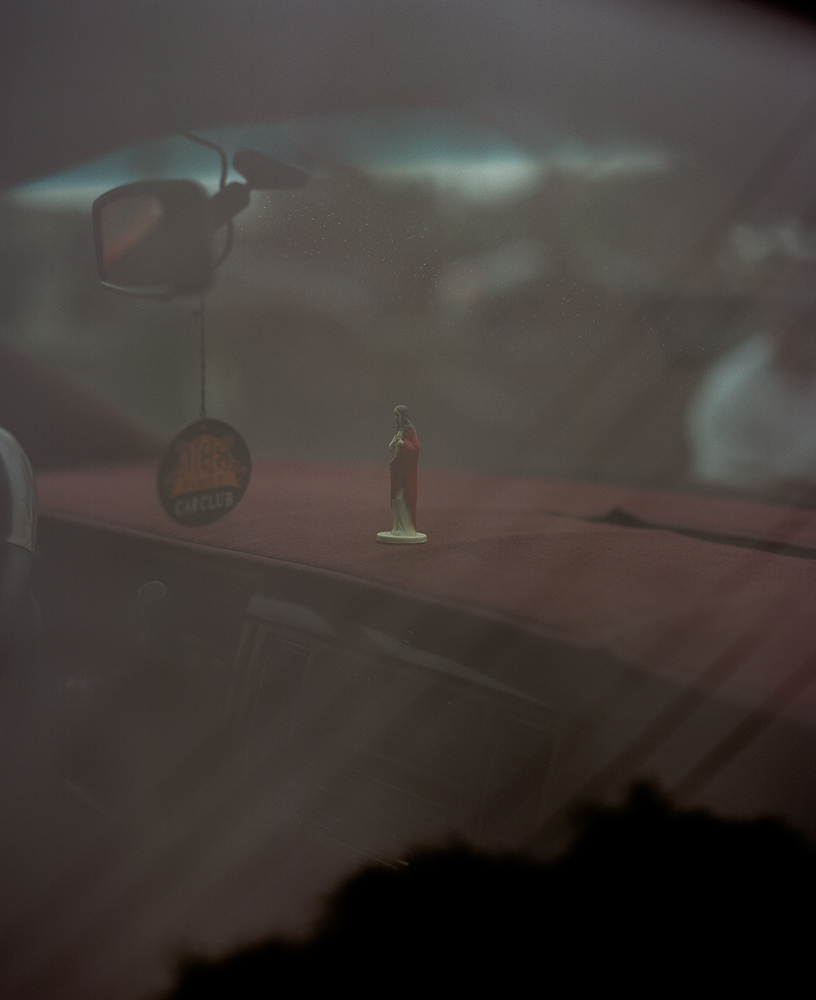

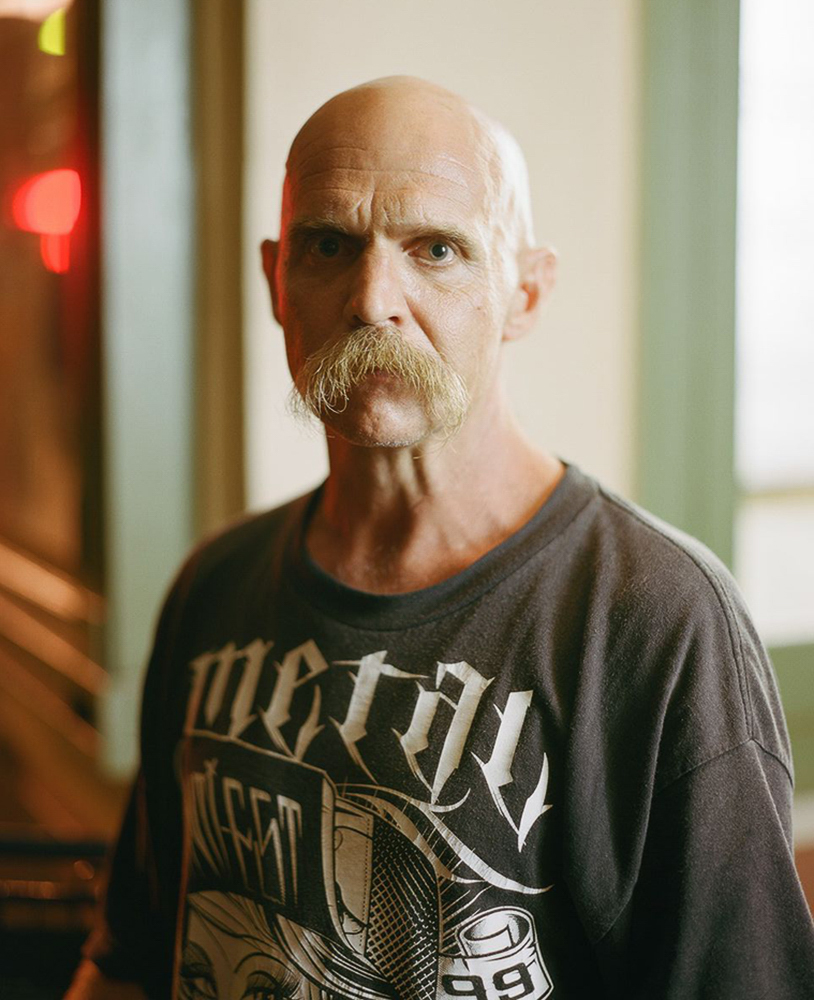

The resulting body of work entitled Imi Haku, establishes an opaque representation of the life and landscape of Hawaii. The photographs, a collection of cues and markers, present an analysis of this once sovereign nation, a poignant study of the state of the union, a journey of lost traditions amidst cultural ambiguity.

Since immigrating in the late 1800’s from Japan, your family is from Hawaii. Beyond the initial time spent there sorting through your family’s interests which launched the project, how do you feel this personal connection influences your photographic authorship or voice?

The main reason I initially returned was to look into the circumstances surrounding the death of my Aunt. I had been led to believe she had overdosed but a friend of my father told me she had in fact been murdered. I went to the Honolulu Police Department and began looking into it. It was surprisingly difficult dealing with HPD, when the files were eventually released I learned she had in fact committed suicide.

After this revelation I was quite angry, I felt cheated. I was lost. This was a person who had promised to build a closer relationship with me after my parents passed away.

Photography can be a way to make sense of things. I began to hitchhike throughout the islands. I found these emotions resonated around me and within the situations I placed myself in. The authorship emerged from those emotions and evolved from there. I began to reflect on terms like assimilation and perpetuation. How these terms play out and manifest themselves around me.

Which of the photographs in this shared portfolio is the most autobiographical or self-expressive? Why?

There are many photographs within the project that are significant to my aunt and my father. The photograph at Waimea Bay peering through the brush towards the group of people on the rock, that was a place I visited with my father 30 years ago. I remember it was a beautiful hot sunny day summer day and running down to the rock across the beach, the sand was so hot, it burned my feet so bad I was in tears. That was so long ago. I’m a million miles from that day now and I can barely see it in my mind. Within the photograph I made at that location I incorporated layers, barriers, loss of detail, separation and distance. An attempt to add metaphorical elements echoing my relationship to that place and memory.

Hawaii must be one of the most photographed states in the United States. How does your project relate to this long-lineage of visual representation/documentation?

There is a perpetuated visual representation of Hawaii. An idyllic vision perpetuated by the tourist economy. And to be fair in Hawaii you are constantly surrounded by beauty. It’s seductive and can lurk around every turn. A curator once complained to me that poor attendance at museums in Hawaii was due to the fact that the paintings on the walls paled in comparison to the views out of a person’s bedroom window.

Daido Moriyama, Henry Wessel and Ansel Adams have all made some work there. I really like the photographs of Daido and Wessel but none of the projects really resonated with me personally.

I was drawn to the work of Big Island based photographer Wayne Levin who made beautiful, important large format black & white work in Kalaupapa, a remote community of individuals living with Hansen’s disease on the island of Molokai. Ed Greevy’s work covering the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, environmental and land use cases in the Kalama Valley, Wai‘ahole and Waikane valleys, Niumalu and Nāwiliwili on Kaua‘i, Honolulu Chinatown evictions, Stop H-3 Freeway, Mākua valley, Mokauea Island, Sand Island, and Kaho‘olawe. Eric Yanagi’s street photography around Waikiki during the early 1970’s has an excellent energy. These weren’t projects put together in a couple of weeks. There was more engagement, there was an exchange, and something was at stake. This was the work that resonated with me. This is what made me feel like I needed to go make photographs.

What do you consider to be the overarching roles of ambiguity and irony in your pictures?

I am interested in the more subtle suggestion of the image and how when placed together, similar to notes of music, they begin to build upon each other, expand and contract narratively as a whole.

Do native and non-native Hawaiians interpret your pictures differently? What response, insight, or feelings do you hope to illicit in all viewers?

Anyone viewing pictures is going to pull from their own personal experience and perspective. There is a relational difference between us all. The perspective and personal experience of someone with more skin in the game, or those that are knowledgeable of Hawaiian history, western intervention and some of the main tenets of the local culture and lore would be more intensely attuned to the work. Otherwise I could see how one might not feel a certain melancholy, an acknowledgment of a great loss, they may only feel irony, a vague familiarity or even humor.

In regards to response, insight or feelings. I don’t want to lead someone through the experience. I simply want to point them in a certain direction and let them find their own way.

Other than your website, where might we see this project? What are you planning as the final form for this work?

It will eventually be a published book. There is still an enormous amount of photographs to go through and I’m in the editing process now.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 14th, 2016

-

Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 13th, 2016

-

Adam Katseff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 12th, 2016

-

Nigel Poor: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 11th, 2016

-

Carlos Chavarria: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 10th, 2016