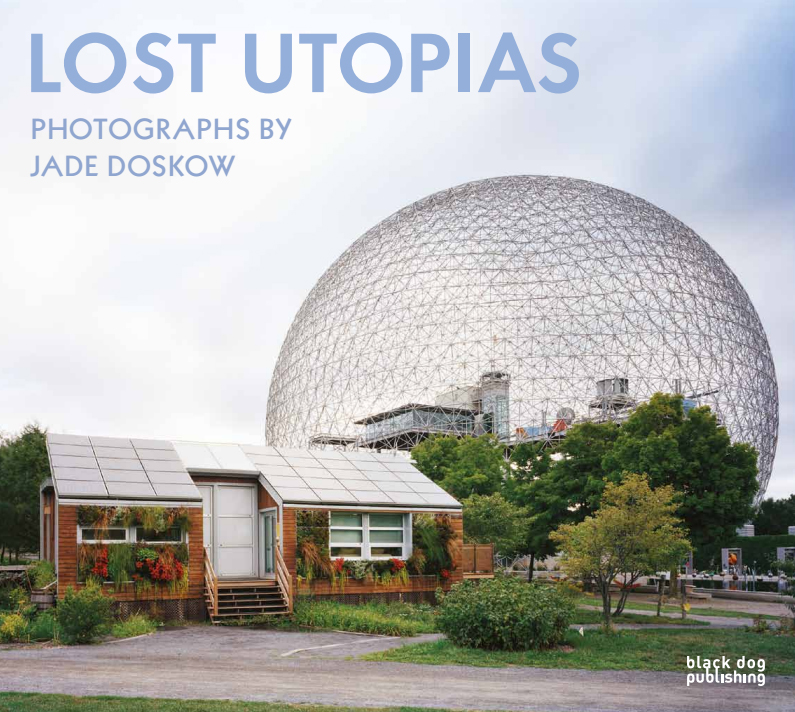

Jade Doskow: Lost Utopias

Architectural and landscape photographer Jade Doskow has always been fascinated by architecture that has outlived its original purpose. For almost a decade, she has focused her attention on architecture once futuristic–that of World’s Fairs and Expos–now in an era of decline. Her project, Lost Utopias considers the visionary and dystopian characteristics of structures, that at one time, inspired and transformed our ideas of space and possibility. So many of the engineering feats of the past that define a city’s skyline,were the products of World’s Fairs: the Eiffel Tower, the Seattle Space Needle, Montreal’s Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, and San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts.

Architectural and landscape photographer Jade Doskow has always been fascinated by architecture that has outlived its original purpose. For almost a decade, she has focused her attention on architecture once futuristic–that of World’s Fairs and Expos–now in an era of decline. Her project, Lost Utopias considers the visionary and dystopian characteristics of structures, that at one time, inspired and transformed our ideas of space and possibility. So many of the engineering feats of the past that define a city’s skyline,were the products of World’s Fairs: the Eiffel Tower, the Seattle Space Needle, Montreal’s Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, and San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts.

Lost Utopias has recently been published as a monograph by Black Dog London and can be purchased here.

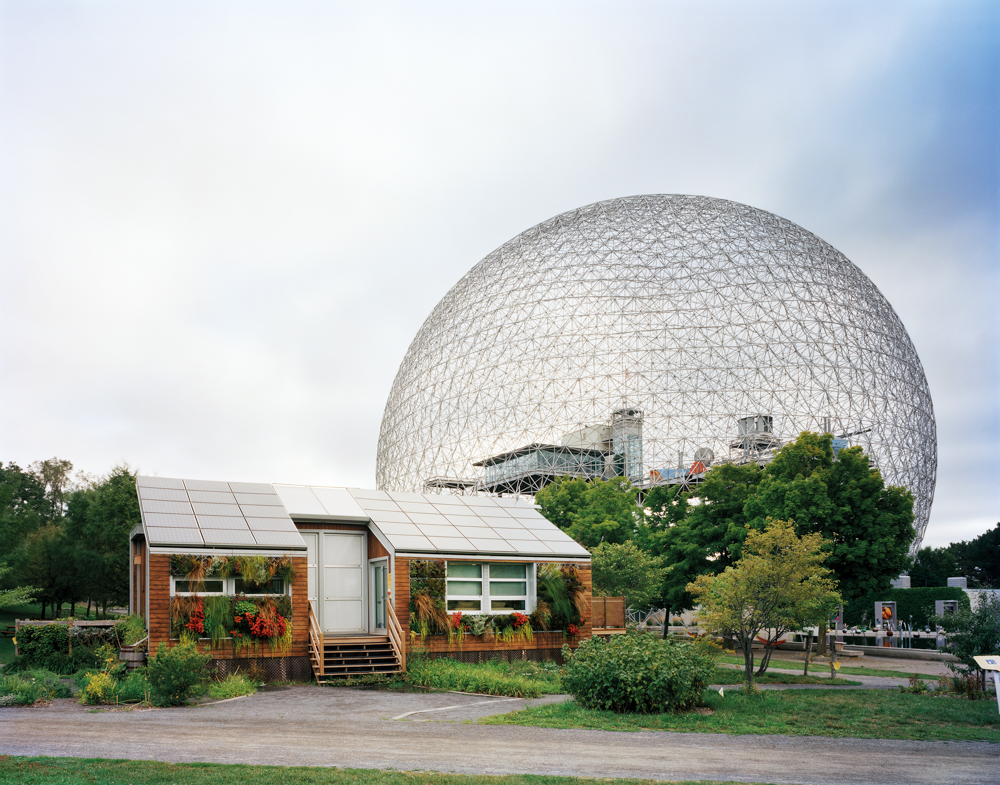

©Jade Doskow, Montreal 1967 World’s Fair, “Man and His World,” Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome With Solar Experimental House 2012

Lost Utopias

Driving West into New York City on the Long Island Expressway after passing nondescript strip malls and housing complexes, something unexpected appears on the horizon in the middle of a park green. A humongous steel globe towers over the park below, and beyond that looms a gigantic ovoid structure, supported by trunky concrete columns and painted in bold red and yellow. Receding beyond it are two towers that could best be described as supernatural landing pads. This is not a sci-fi movie set, but rather the site of the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens, New York. The globe is the icon from this event, the Unisphere (weighing in at 900,000 pounds of solid steel) and the other structure is the New York State Pavilion, designed by Philip Johnson.

©Jade Dostow, Paris 1937 World’s Fair, “Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne”, Graffiti, Palais de Tokyo 2007

World’s fairs are typically held on the peripheries of cities, taking over huge, unused plots of urban land and transforming them, temporarily, into magical, otherworldly mini-cities populated by over-the-top architecture and stunning exhibits of culture and technology. I have been visiting these unique sites and photographing them, capturing visually the dynamic paradox between the old fair structures and their relationship with the here and now, as often they were built to represent specific utopian ideas from the era in which they were created. I feel, visiting these sites, that these places are a kind of time warp that crystallizes the pure essence of past decades and centuries through the remaining architecture and landscaping.

It was a trip to Seville that originally sparked the idea. I have always been fascinated by architecture that has outlived its original purpose. In Seville I was struck by the immense contrast between the old city on one side of the Guadalquivir River and the 1992 fair site across the water, modern, somewhat garish, somewhat abandoned and also somewhat in use. It was odd to say the least. After researching the 1992 fair when I returned to New York, I learned about an event that attracted millions of people, that many countries wholeheartedly participated in, and that forever changed the architectural landscape, transportation and infrastructure of Seville. I returned to Seville and made photographs depicting the wild variety of how the fair site was being utilized: the RTVA (Radio y Televisión de Andalucía) building (housed in a former pavilion building), an abandoned fountain filled with algae and beer cans, the old Environmental Pavilion, stately and unused, the bushy landscaping taking over the building in every direction.

©Jade Doskow, New Orleans 1884 World’s Fair, “World Cotton Centennial,” Ore (From Alabama Iron Ore Exhibition) 2014

In New York I took up visiting the 1964 site every few months, revisiting Johnson’s old pavilion and photographing it during different seasons until I felt I had fully captured the spirit of the place. Since I last photographed it in 2013, the building has been assigned historic landmark designation although there is a serious lack of funding to actually renovate. A group of dedicated volunteers has taken their own energy and money to start bringing the building back to life.

©Jade Doskow. Vancouver 1986 World’s Fair, “World Exposition on Transportation and Communication,” McBarge 2014

For many people world’s fairs have lost their relevance simply because we now are a global, high-tech economy; one can learn about the latest inventions on their iPad instead of traveling around the world. In the early expositions this was not the case. It was at 19th and early to mid- 20th century world’s fairs that the public first experienced elevators (1853 Dublin), the telephone (1876 Philadelphia), and electronic music with moving film projections (1958 Brussels, designed by Le Corbusier), just to name a few. These fairs were the place to experience the latest and greatest in human achievement.

©Jade Doskow, San Antonio 1968 World’s Fair, “The Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas,” Tower of the Americas Ticket Booth 2013

World’s fairs still take place every 2-4 years (most recently in Milan, Italy) and continue to offer countries a chance to compete and create cutting-edge national pavilions and show off their latest technologies, much like the original fairs of the 19th century. (The United States did not pay its membership dues to the Bureau of International Expositions in Paris and cannot host any upcoming expositions). The pavilions in Shanghai 2010 enjoyed international stardom for their daring, exciting designs. As Europe and then the United States were the industrial and cultural leaders of the 19th century, the rest of the world is catching up in the 20th and 21st centuries, and the countries and cities that choose to invest in World’s Fairs are the countries that are enjoying more recent socio-economic and cultural successes.

©Jade Doskow, San Diego 1915 World’s Fair, “Panama-California Exposition,” Museum of Man / California Tower 2013

I have discovered that people become attached to the bizarre fair structures left in their hometowns. What remains after the fair closes is often more a bit of luck (the building didn’t burn down, there was not enough money to demolish) than planning, and through my pictures I illustrate the arbitrary nature of what we choose to keep, discard, or reuse on these sites. In the newly published monograph of this work, Lost Utopias, the pictures illustrate the full scope of how these extraordinary, temporary events permanently affect both the cities in which they are held and the cultural mythologies that can still be gleaned from the remaining fair architecture, mysterious, grand, poetically utopian.

©Jade Doskow, San Francisco 1939 World’s Fair, “Golden Gate International Exposition,” (Originally) Palace of Fine and Decorative Arts, Entrance 2015

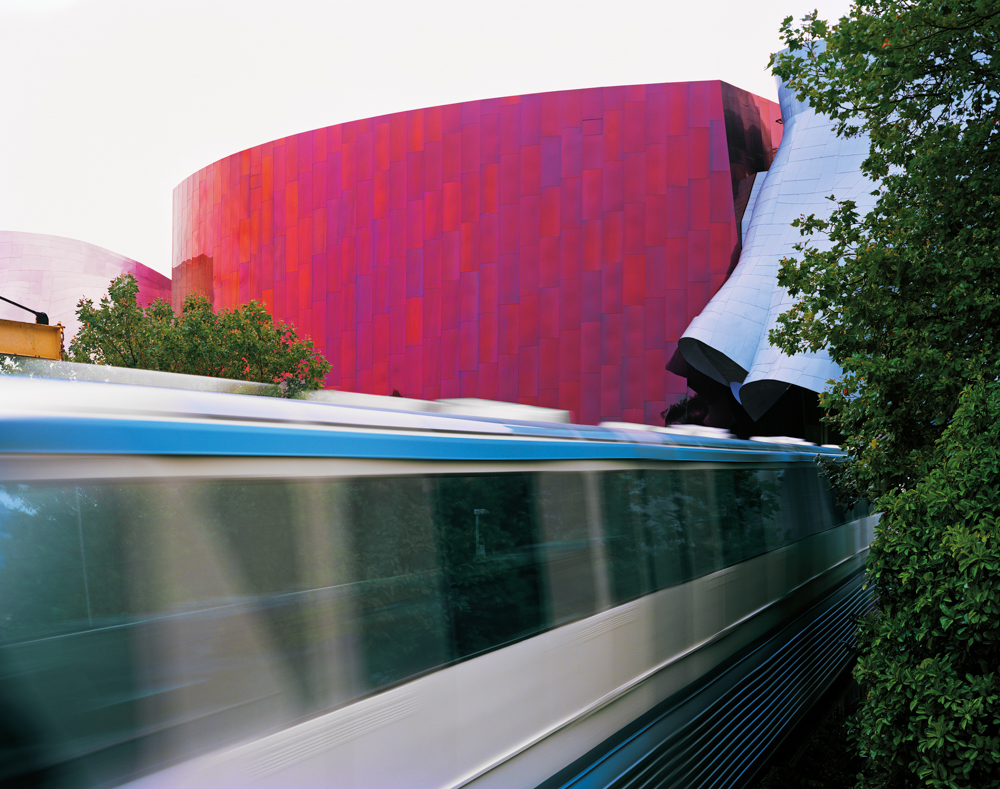

©Jade Doskow, Seattle 1962 World’s Fair, “Century 21 Exposition,” Monorail with Gehry-Designed EMP Museum 2014

©Jade Doskow, New York 1964 World’s Fair, “Peace Through Understanding,” New York State Pavilion, Winter View 2014

©Jade Doskow, Vancouver 1986 World’s Fair, “World Exposition on Transportation and Communication,” Science Center/ Expo Center ‘86 2014

©Jade Doskow, Seattle 1962 World’s Fair, “Century 21 Exposition,” Science Center Arches at Night 2014

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026