Stacy Platt: Waterlogged

Sometimes unfortunate life events create opportunities to see things anew, allowing for different incarnations and considerations. When photographer Stacy Platt discovered a lifetime of journals destroyed by water, it allowed her an opportunity to consider the transience of objects, the idea of memory, and create artful examinations of what remains.

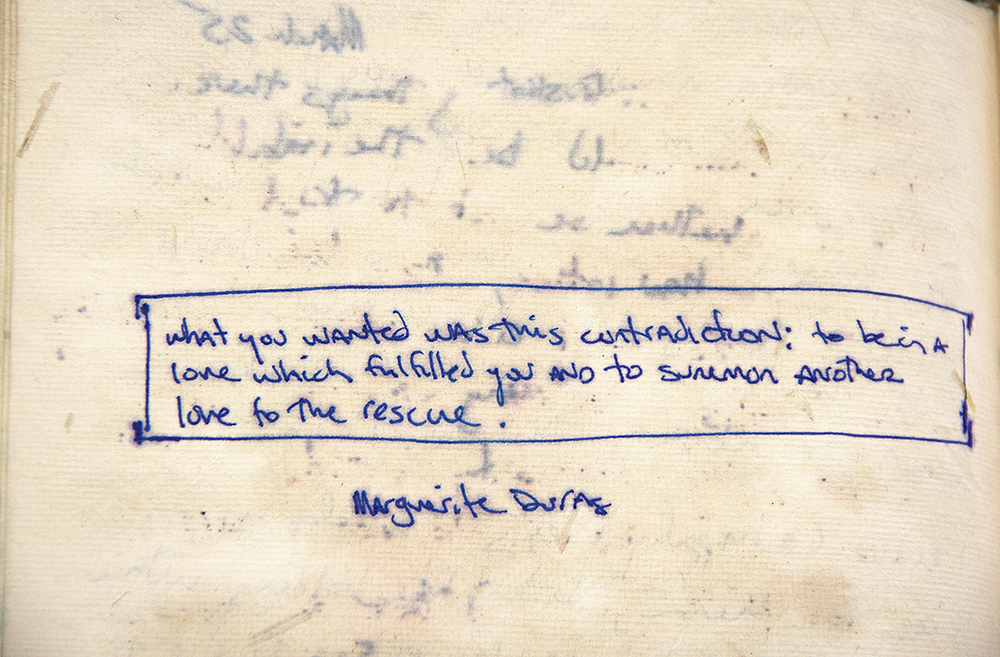

Stacy uses photography to speak about vulnerability, memory, loss and the practice of everyday life. Influenced by the writing of Marguerite Duras, the films of Kar-Wai Wong and the multivalent art of William Kentridge, Stacy’s work is characterized by an interest in exploring the multiple—and sometimes unreliable—versions of self and personal history that we all contain, as well as the symphony of incoherent, contradictory threads of collective identity that serve to both constrict and connect us to one another.

She received her B.A. in Humanities from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and her M.F.A. in Photography from Columbia College of Art in Chicago. Her work has been shown at the Houston Center for Photography, the Midwest Center for Photography, the University of North Dakota’s Memory, Bone and Myth exhibit, many online-curated projects and exhibitions, and she was a 2015 Critical Mass finalist. Stacy is presently an Instructor of Photography at the

University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, as well as the editor for the Society for Photographic Education’s Exposure journal. She maintains a portfolio site of her photographic work at http://www.stacyjplatt.com, and has been composing longform essays on photography at http://www.the-space-in-between.com since 2004.

How do you tell yourself to yourself?

What is your process for remembering, for mediating experience, for archiving the self?

I am a person that believes in synchronicity and signs. When one follows the other or when one is repeated often enough in a short enough time span, I am compelled to pay attention. The series Waterlogged began this way.

At the time of its making, I had been caught in the undertow of one of those unusually serious and draining periods of life: job loss, a parent dying, my first child born less than two months before that death. I had been in it: everything coming all at once and from all sides. Any one of those single events is an opportunity calling for both reflection and transformation. All of them at once have the capacity to take all your points of reference from you, and leave you reeling. It is the kind of juncture in which, to paraphrase Rilke, “You must change your life or die.”

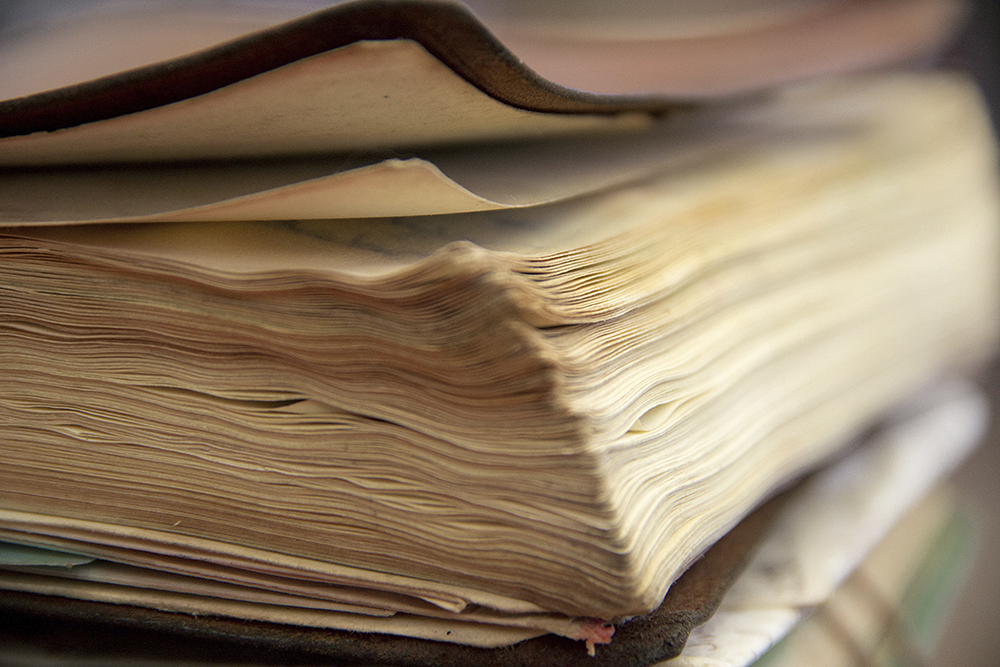

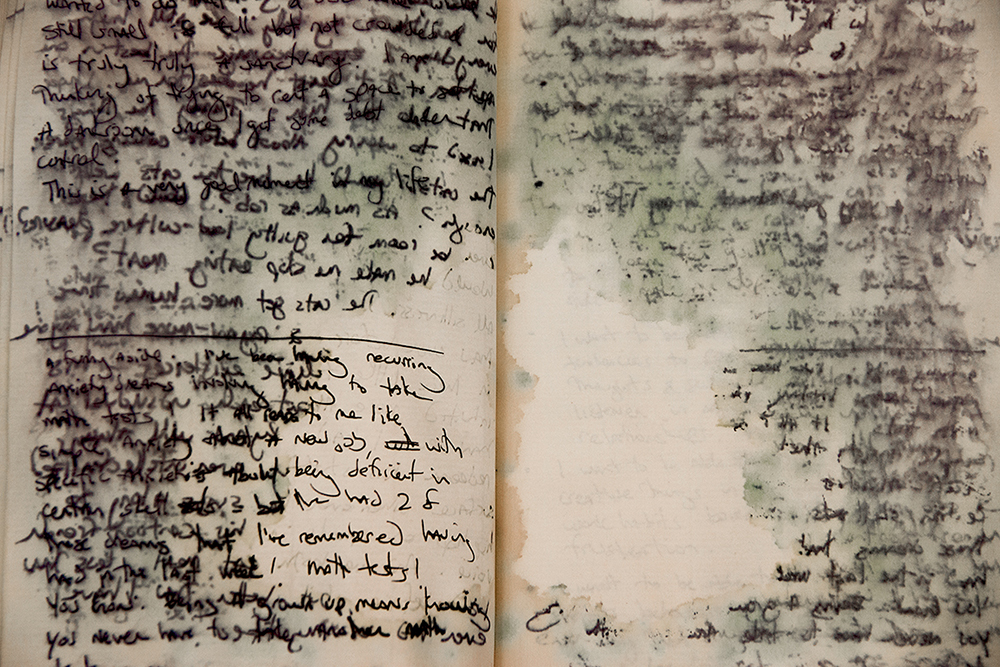

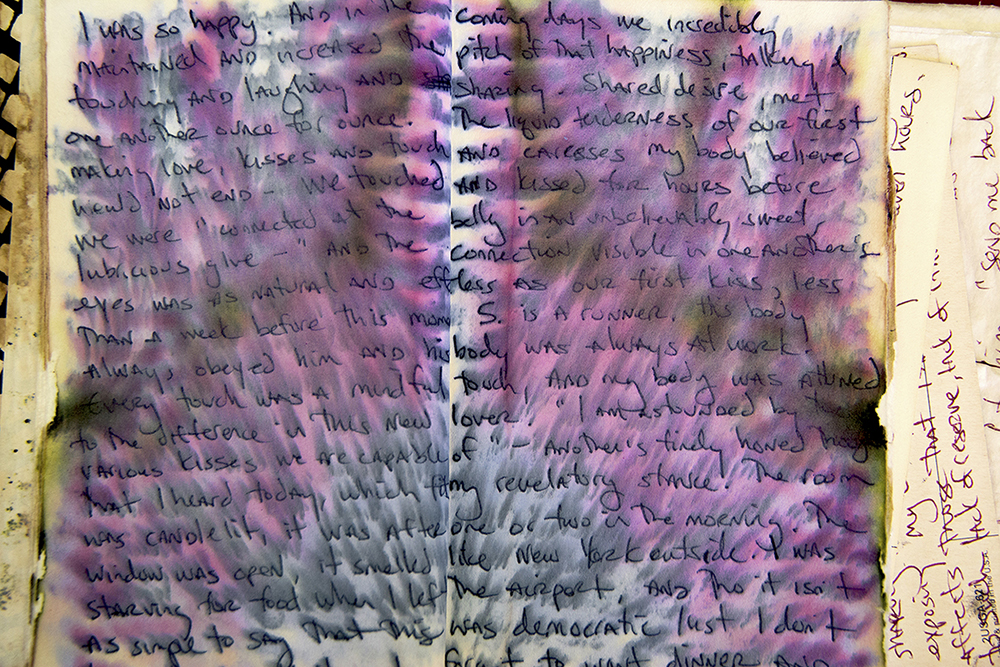

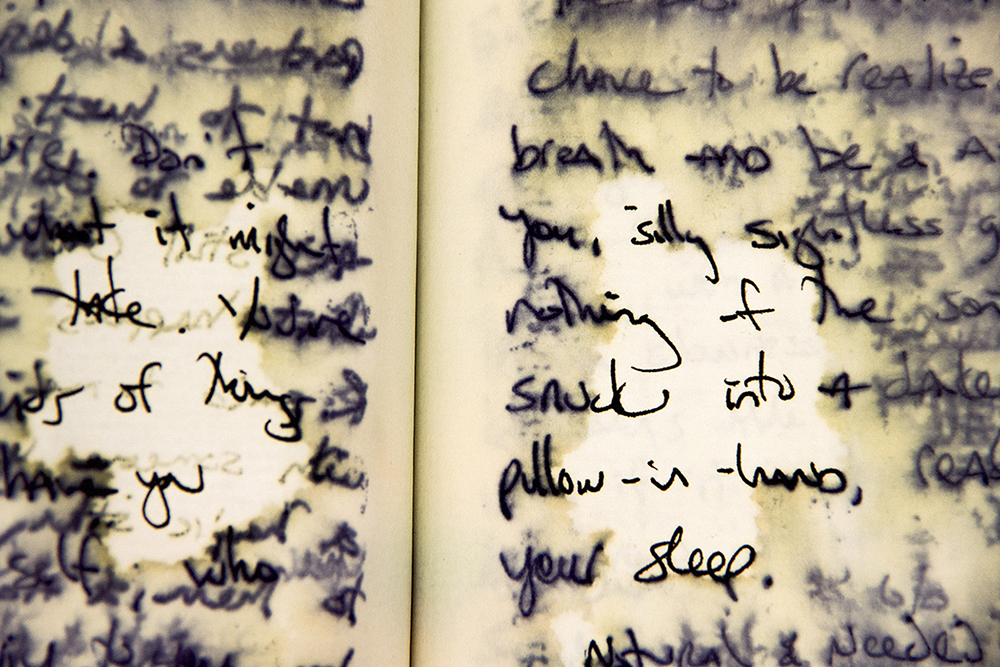

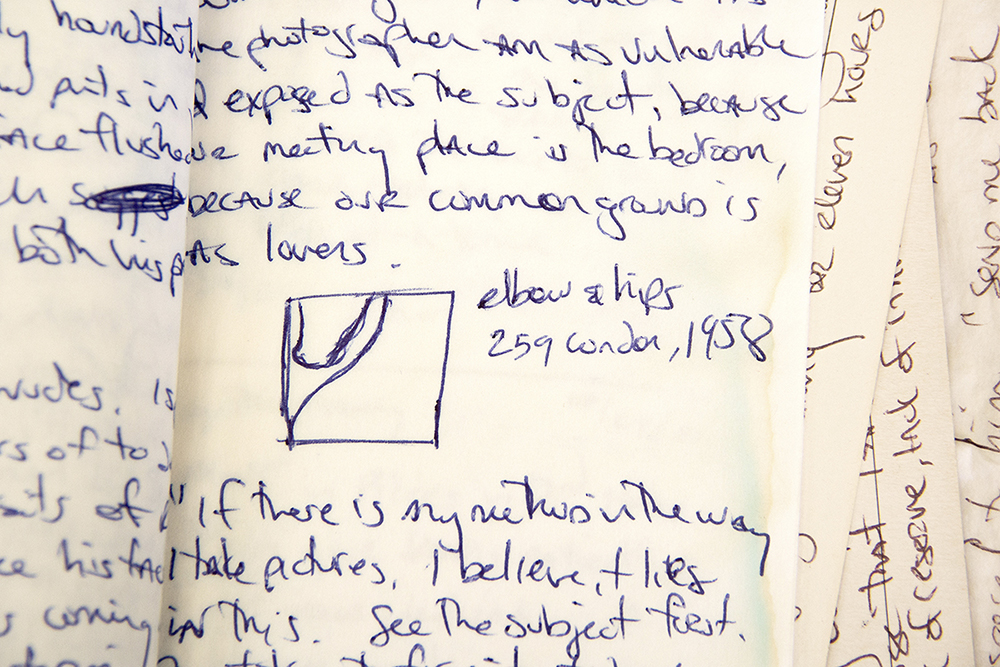

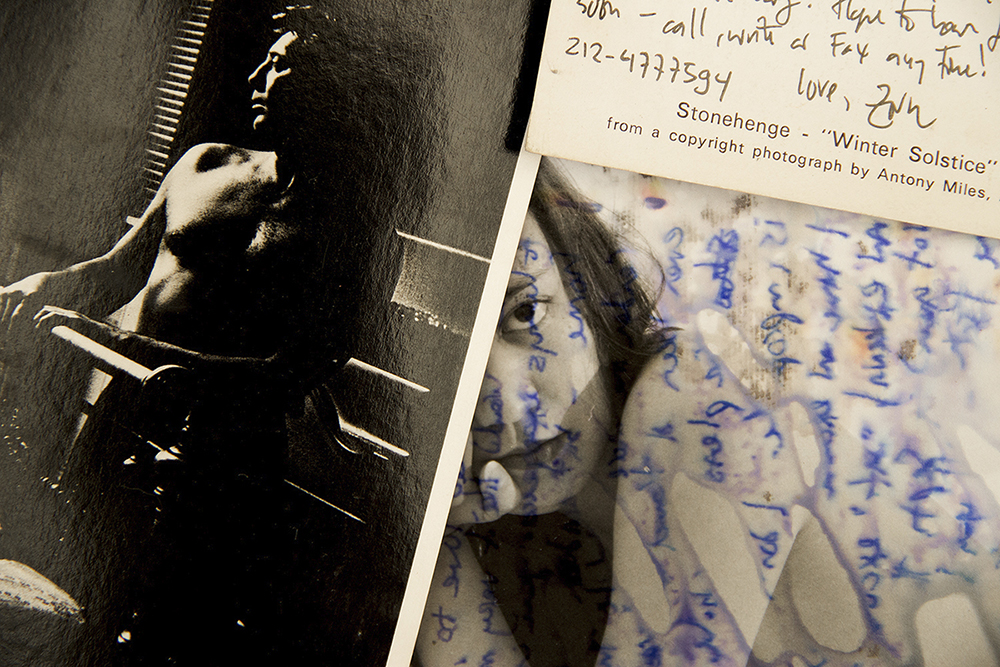

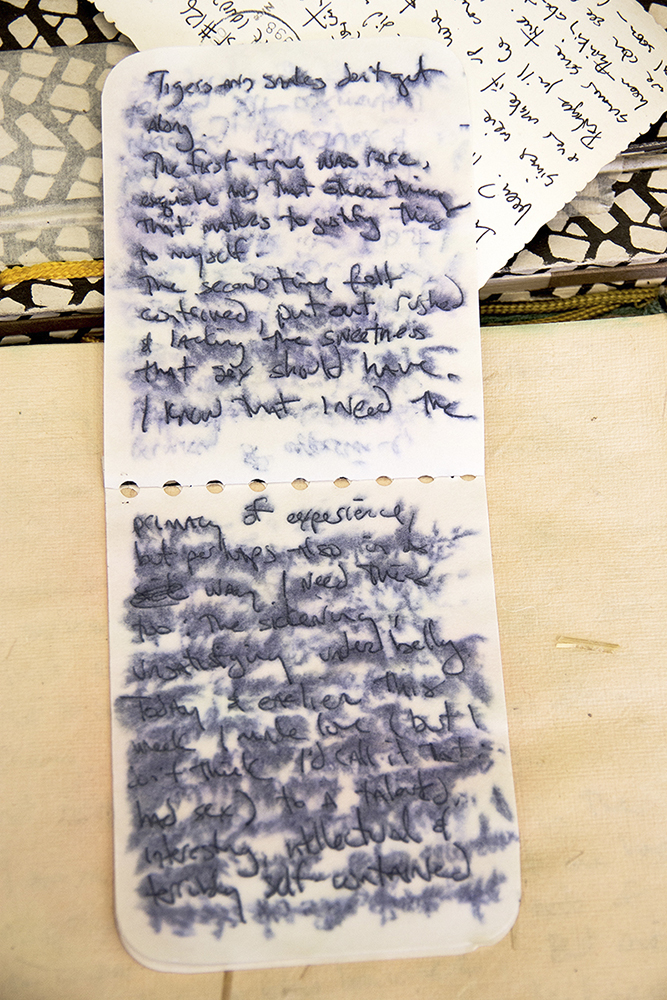

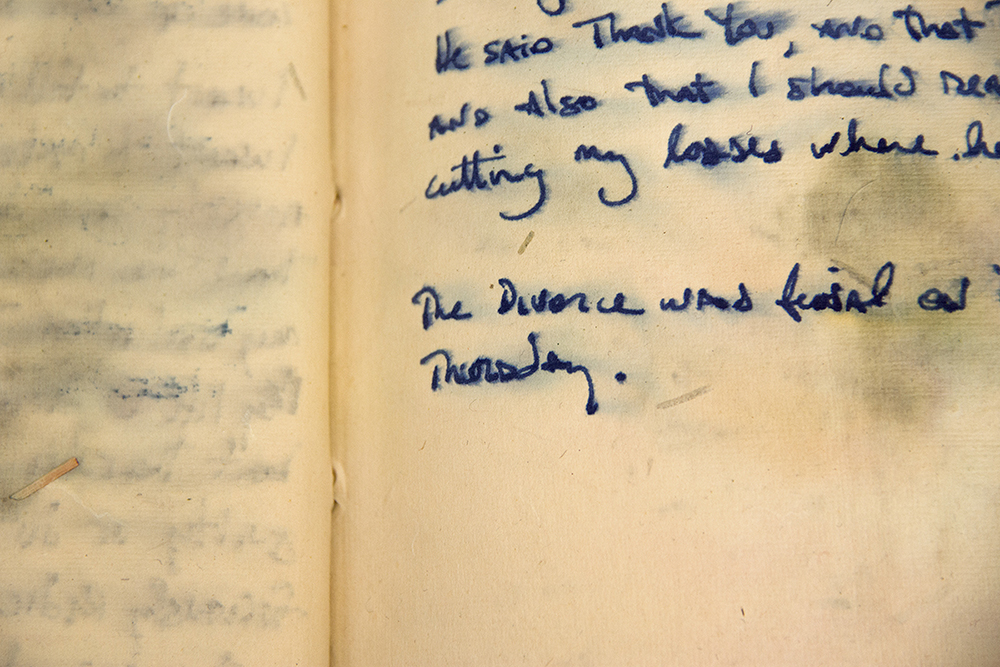

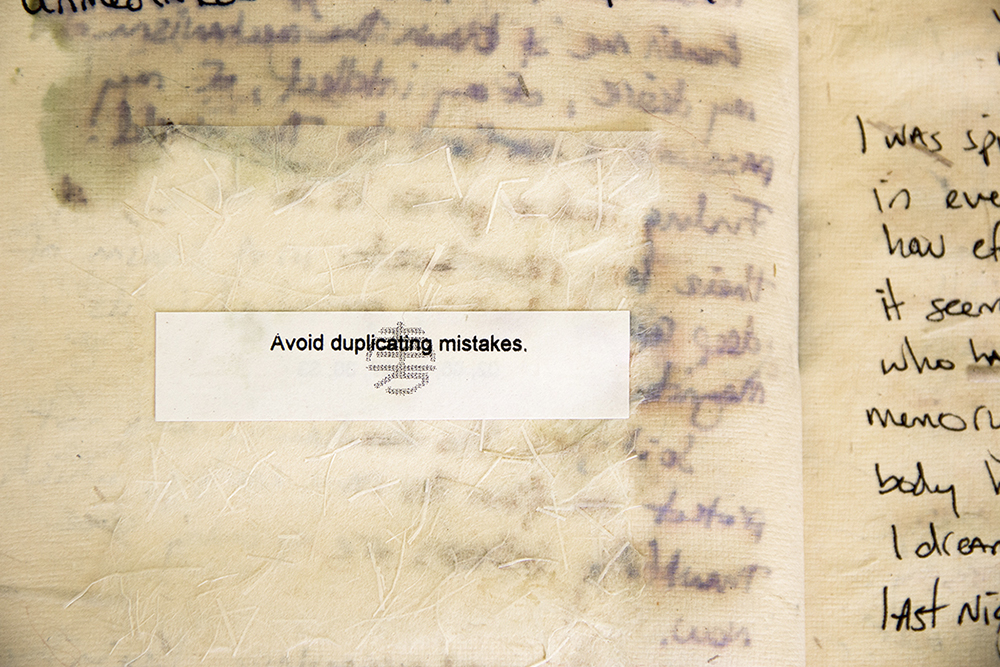

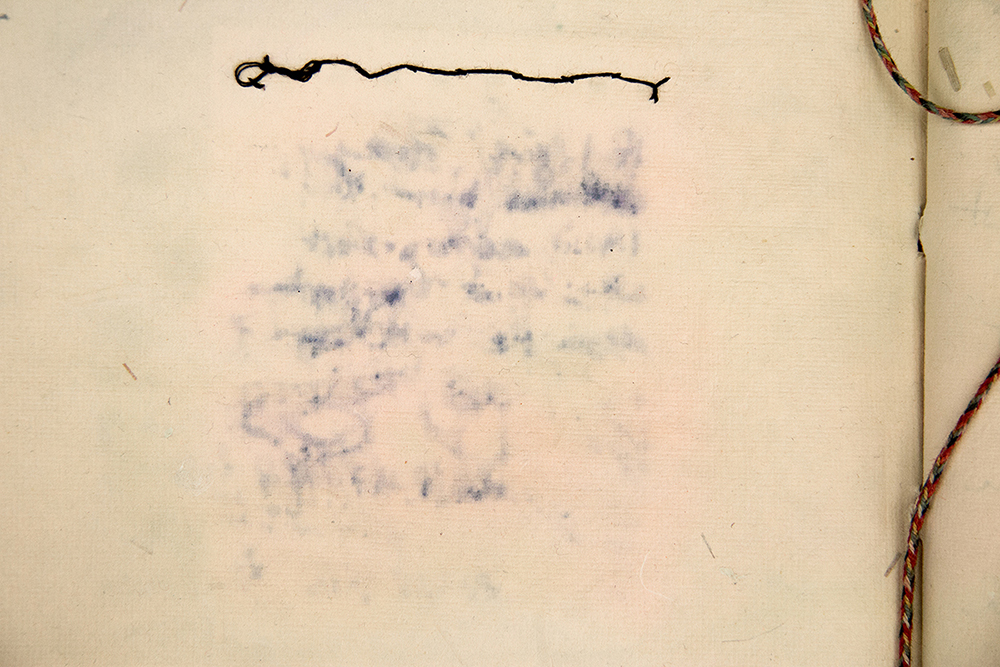

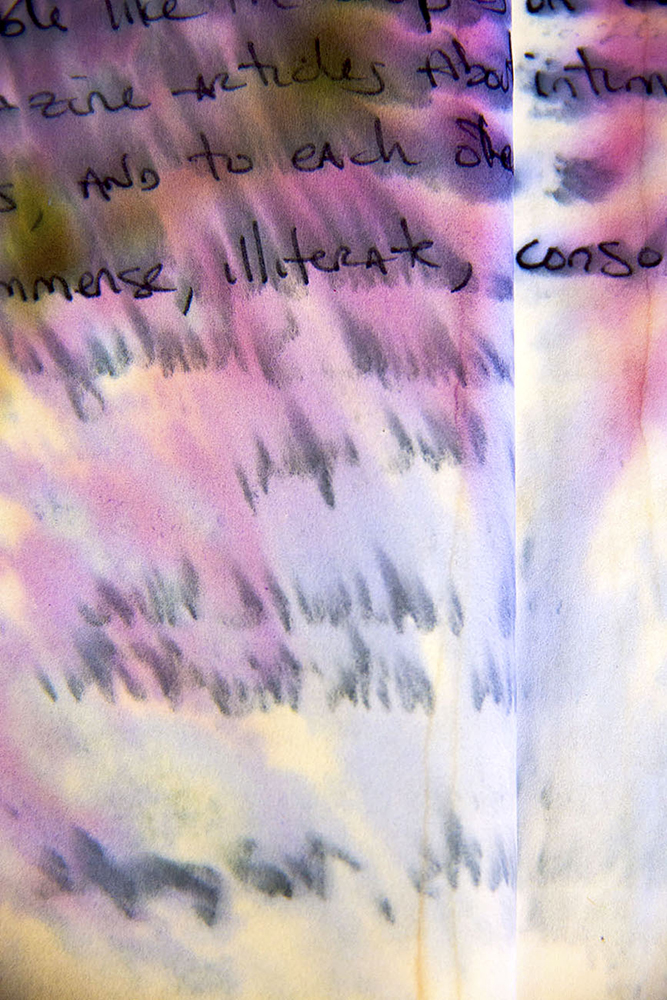

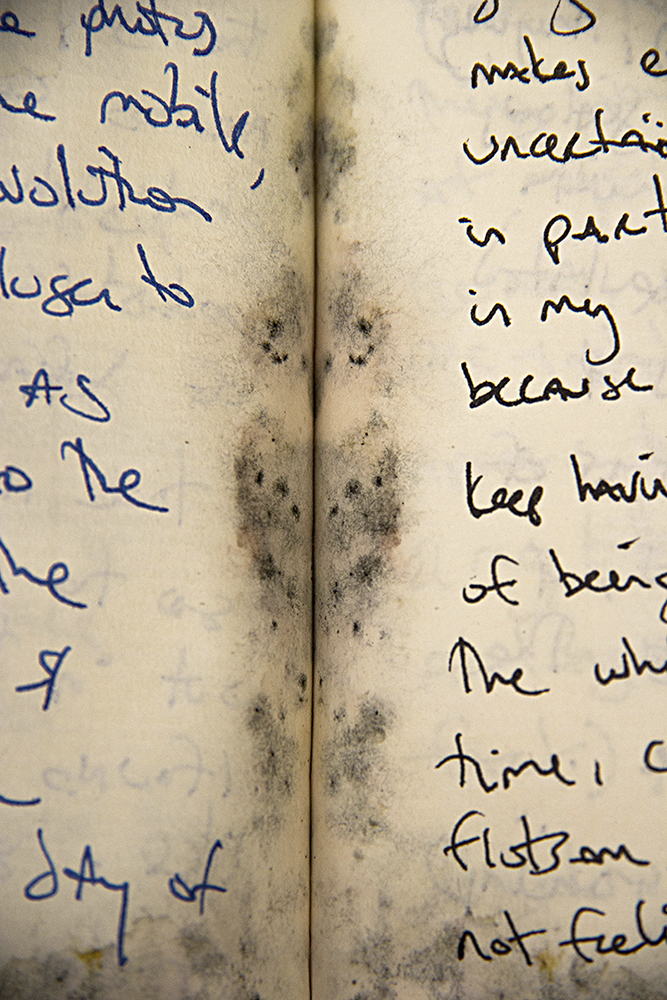

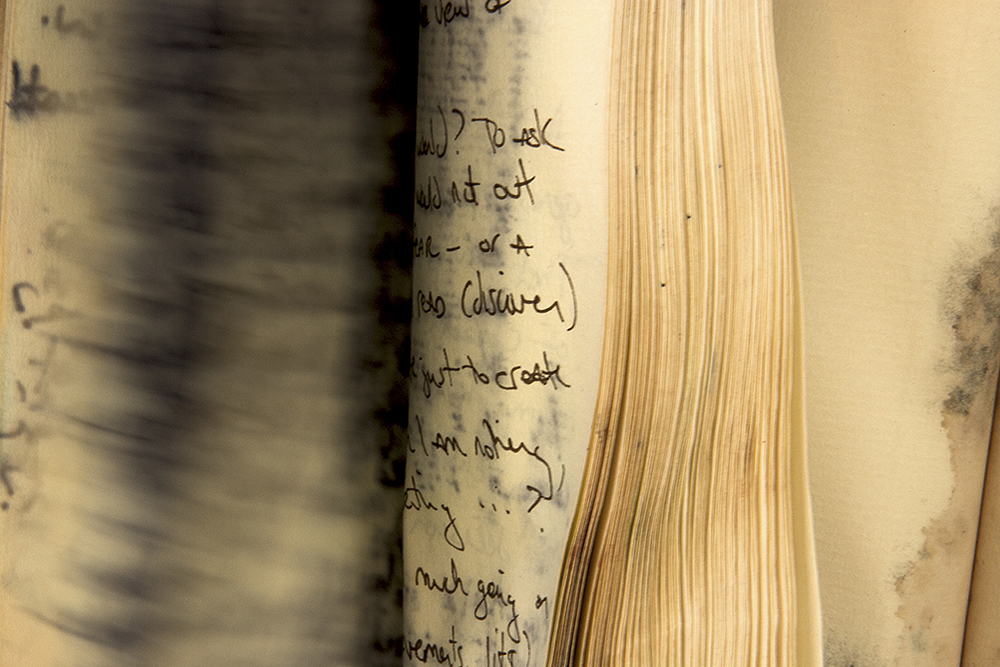

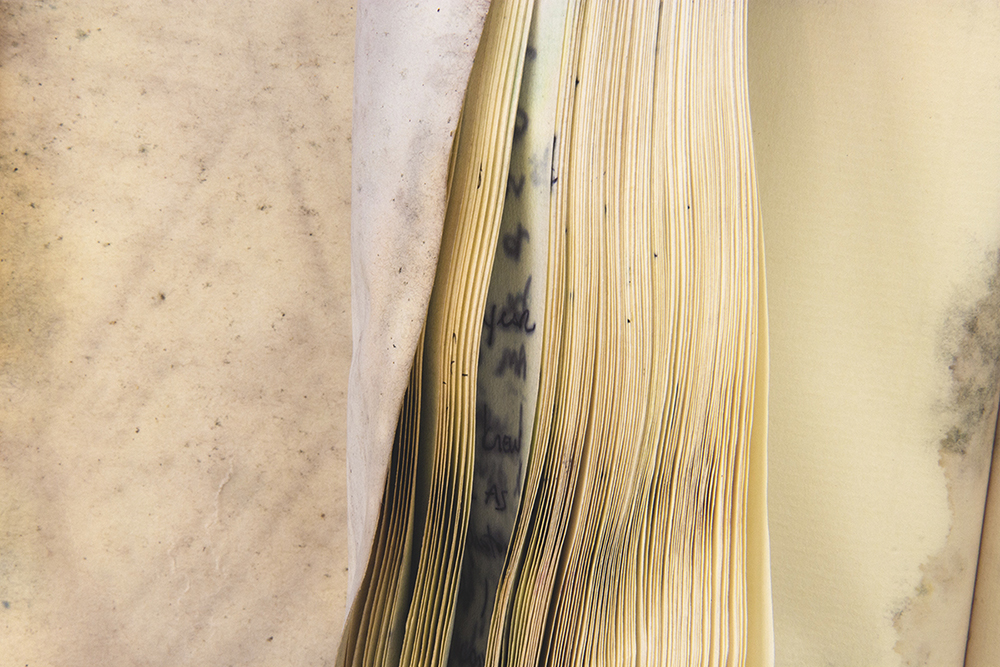

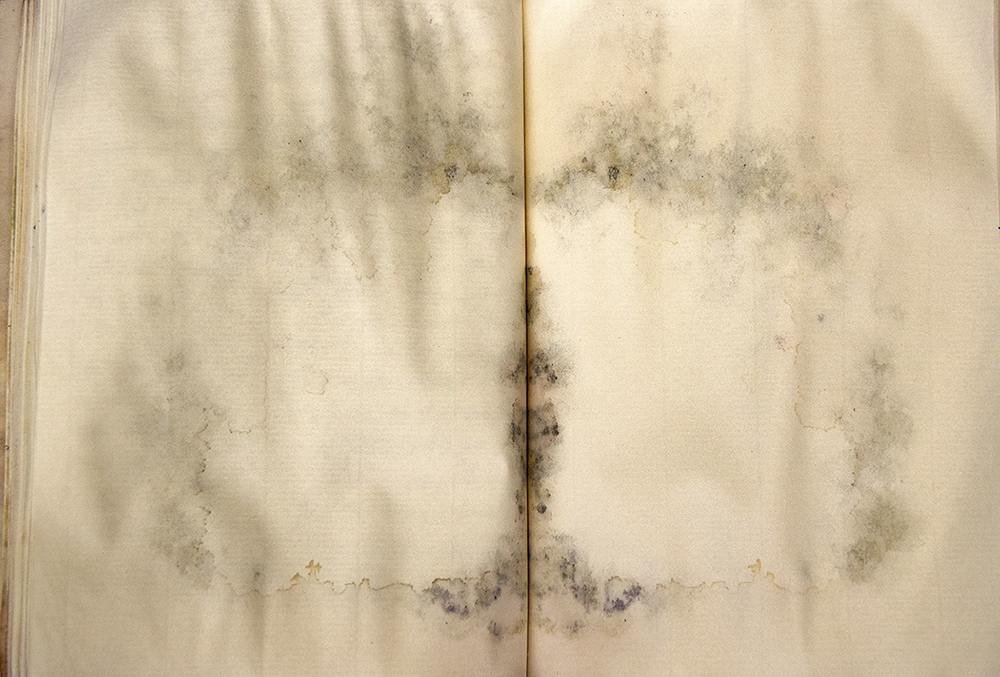

After a night of torrential rains, I opened a closet where all of my journals were stored. They were all—twenty years worth— soaked through with storm water. Stacked neatly atop one another, swollen and sticky with gum residue and running ink. Destroyed. Or in the active process of becoming so. Simultaneously mystified and mortified by witnessing my past bleed out into oblivion, I began to photograph them.

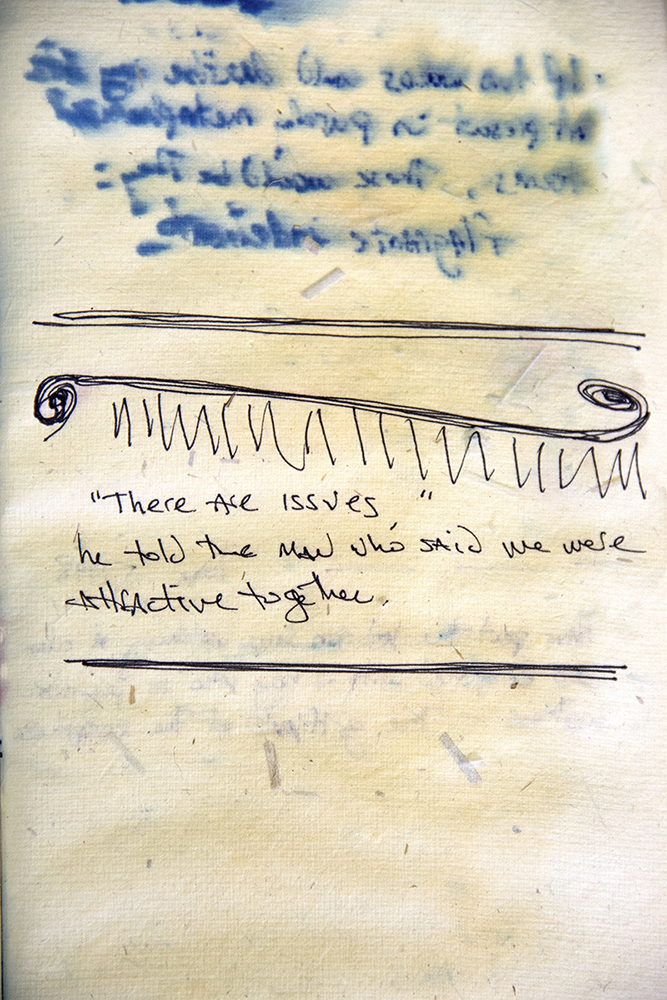

First loves. Failed loves. Bad choices. Life-changing travel. Things that inspired me. My unwritten, unknown future, written and wondered about by a past self. Some of it still legible. Much of it looking like another language, or pentimenti, or secret code.

Synchronicity and signs. It seemed particularly inauspicious that of the entirety of my household goods, only these personal historical objects were affected. The thing that struck me most in looking at these is the revelation that is handwriting, which has almost become anachronistic, a throw- back to an inefficient and sentimental way of doing things and communicating. Who writes in longhand anymore? When you once were able to identify someone, in voice and person, by their hand, what takes the place of that now? Their email address? Their social media handle? Caller ID?

When my mother died last year, I immediately set about searching for things in my possession that she had written to me. Something about her handwriting was evocative in a way that little else was. Throughout her prolonged sickness, I found witnessing her handwriting deteriorate as her illness progressed touching and poignant in ways that were gut-wrenching, reminding me that even while she was still alive that everything shifts and will come to an end. One’s entire life and conception of self, how they understood time, and people, what they valued and what they reviled—all the things they both could and could not say, that they knew or never cared to know, that all ends when they do. What’s left behind is everyone else’s interpretation. Their conjecture of another’s lived life. There are moments in life when you are confronted with the reality of the insignificance

of your own specifics. These images are the visual evidence of my submitting to that reality.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025