Olivia Parker: Vanishing in Plain Sight

When I was in college, my mother gave me a book of Olivia Parker’s photography. I was intrigued by her ability to transform objects into tableaus of beauty, memory, and imagination, work that comes from an internal vocabulary and creates a unique language of objects. Her photographs are quietly profound, so I was thrilled to meet Olivia last year at the Griffin Museum where I could express my long time appreciation for her talents.

Olivia has a new exhibition, Olivia Parker: Vanishing in Plain Sight, that recently opened at the Robert Klein Gallery in Boston running through June 24, 2017. It is a deeply personal series, born from her husband’s journey through Alzheimer’s Disease. John Parker passed away in December of 2016 and the experience moved her to explore new grounds of “self-portraiture and dramatic grid sequences, while still retaining the vivid color and abstract liveliness that have become the signature of her still life work.” Included with the exhibition is a book under the same title that can be ordered through the gallery (hank@robertkleingallery.com).

After graduating from Wellesley College with a degree in the history of art, Olivia Parker began her career as a painter. Parker became involved in photography in 1970 and remains largely self-taught, making ephemeral constructions to photograph and experimenting with the endless possibilities of light. Her compositions incorporate her extensive knowledge of art history and literature and reference the conflicts and celebrations of contemporary life. She has had more than one hundred solo exhibitions in the United States and abroad and her work is represented in major private, corporate, and museum collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

When Parker started photographing, she worked exclusively in black-and-white, using large format cameras: 8 x 10″ up to 12 x 20″. The split-toned contact prints she made possessed a rich tonal quality that has brought her continued renown in the photography community. Parker eventually switched to digital technologies, mastering Lightroom as she did the darkroom, but she continues to explore the same concerns and aesthetics as she did in the very beginning of her career.

Portfolios of Parker’s work have been published in Art News, American Photographer, Camera, Camera Arts, The Sciences, and other magazines in the United States, Europe and Japan. Parker has had three monographs of her work published: Signs of Life (Godine, 1978), Under the Looking Glass (New York Graphic Society, 1983), and Weighing The Planets (New York Graphic Society, 1987). She has lectured and conducted workshops extensively in both the United States and abroad. In 1996, Parker received a Wellesley College Alumnae Achievement Award. Residencies include Dartmouth College in 1988, the MacDowell Colony in 1993 and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1997.

Vanishing in Plain Sight

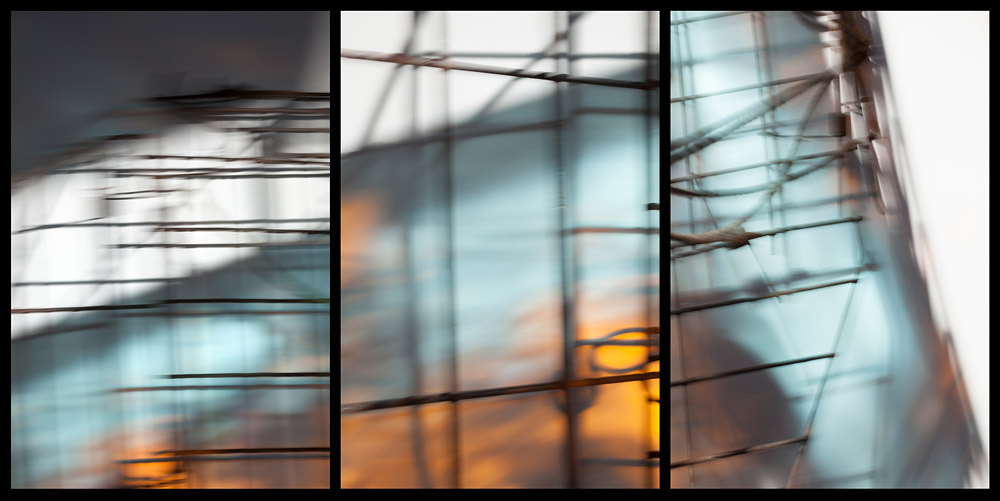

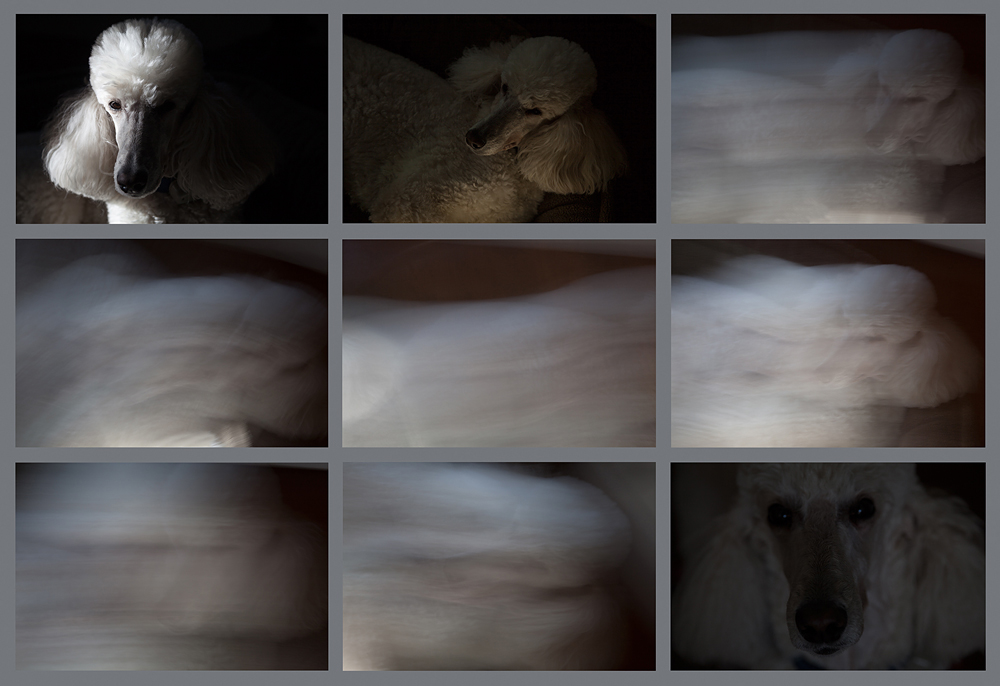

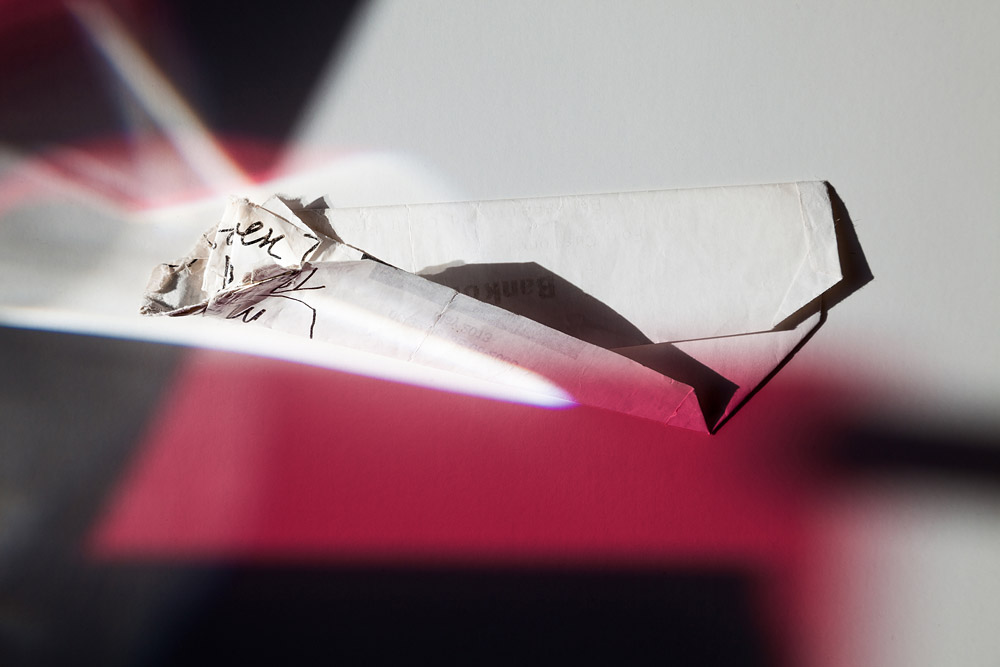

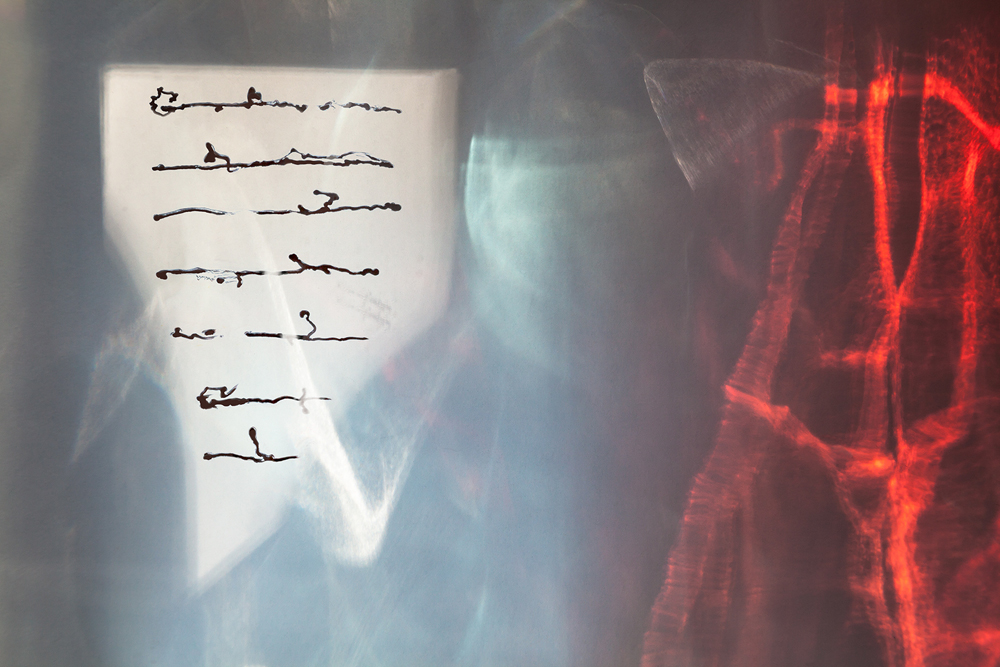

“Vanishing in Plain Sight” is my imagination’s journey through my husband John’s continual changes due to Alzheimer’s disease. I began with tangible things: the notes he wrote to help him remember and the office supplies he feared would be gone. When a subject or a camera moves during an exposure the subject disappears partially or entirely. I found that this characteristic of photography was well suited to the images I wanted to create next. As John became more and more disconnected from the world around him my photographs began to depart from what my eyes saw. The assumed connection between photography and reality remains giving voice to my imagined images.

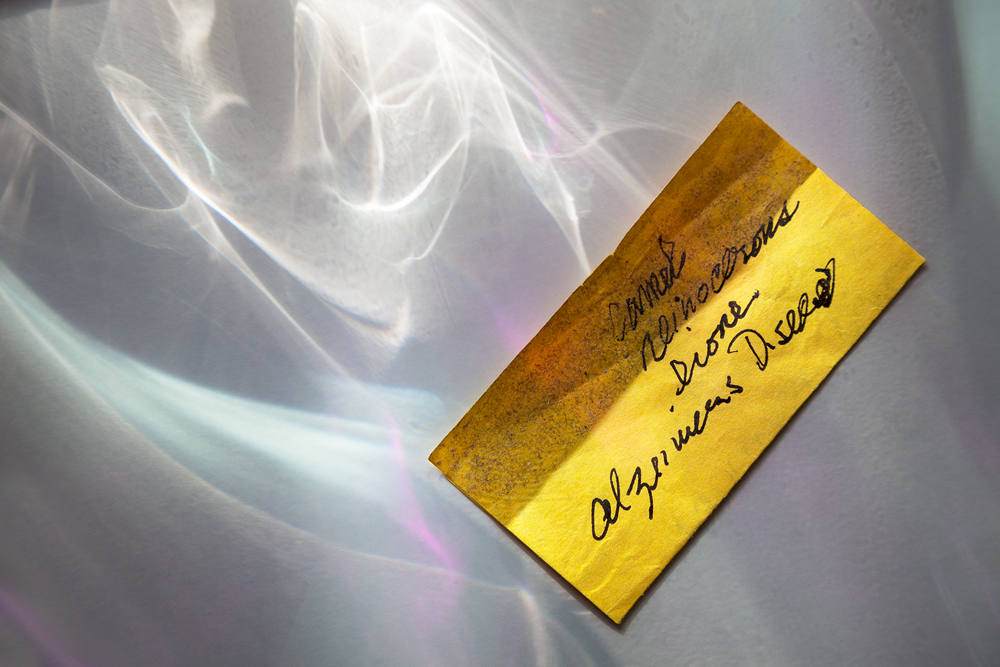

As soon as I had about 20 photographs I began writing short texts to go with them. I then made a small online book of the images and texts and began giving them to friends. The gifts unleashed a torrent of conversation about a subject that people often find hard to talk about. John never acknowledged that he had Alzheimer’s. The day he wrote it down the doctor asked him to do it and spelled it out for him. He did not want me to tell anyone there was something wrong with him. Caregivers who feel that they cannot talk to others about a spouse or parent’s condition can become more and more isolated.

Since the time of John’s diagnosis I have tried to learn about the human brain, its’ unfathomable complexity and beauty of structure. Although I will only ever know a small fraction of evolving neuroscience, I have learned enough to have a little understanding of the research being done on Alzheimer’s. After so many years of working with light I like the new idea that the application of light at a specific frequency is repairing neural connections in mice, enabling them to retrieve lost memories.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026