South Africa Week: Ilan Godfrey

©Ilam Godfrey, Fraser Alexander Tailings (Lonmin – Western Plats – Dam 5 Tailings Complex), Wonderkop, Marikana, North West, Western Limb Storm clouds hang overhead as strong winds carry dust tailings into the community. Informal settlements around mining operations in Marikana and the surrounds have been directly affected by dust pollution, further exacerbated in windy conditions. Dust suppression systems have been installed on the tailings in an attempt to control high dust levels. However, with communities living in close proximity to these tailings, the efficacy of such systems is limited. Community members complain that the high dust levels contaminate food and water, and many children in the area suffer from asthma and other respiratory-related illnesses. Professor Eugene Cairncross from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology writes, “Health impacts from dust include breathing and respiratory systems, damage to lung tissue, cancer and premature death.”

The mining of natural resources has shaped South Africa political and economic history more than any other industry. The discovery of gold and diamond deposits in the late nineteenth century led to the founding of the cities such as Johannesburg and Kimberley. Laws and practices developed in response to needs of the mining industry incrementally disenfranchised indigenous populations and helped form the foundation of the apartheid system. Even after first democratic elections in 1994 the mining industry continues to exert a pervasive influence in South Africa: low wages, continued reliance on migrant labor, unsafe working conditions, and damage to community water supplies are a few of the things that make up the industry’s footprint.

In 2013 Ilan Godfrey completed an extended photographic survey of the widespread health and environmental impacts of the mining industry in South Africa, which he published as his first monograph, Legacy of the Mine. Over a two-and a half year period Godfrey traversed the country, visited communities affected by natural resource extraction, and photographed individuals and sites transformed by the industry. His project focused on a group of key minerals that shaped South African history — gold, diamonds, coal, asbestos, and platinum — but through his work he became aware of the extent of impacts exerted by each mineral. “I realized there was an incredible amount a wealth of stories, an incredible amount of information that deserved to be expanded upon or investigated further,” Godfrey recalls, “and the one of the key minerals that I felt deserved to be documented and understood further was platinum.”

©Ilan Godfrey, Andisiwe Nkotha, 17, in the backyard of her parents Mncedisi and Nokhwezi’s home, Skomplas Hostel, Wonderkop, Marikana, North West, Western Limb Mncedisi Kidman, Nkotha arrived on the platinum belt in 1989, and soon found work at a platinum mine in the area as a loader driver. In 1992, he wedded Nokhwezi Paslina Nkotha, and they took up residence at a hostel for married mineworkers. The Nkothas were content in their new home. Mncedisi worked long hours providing for his growing family – until his health began to slowly deteriorate. After several visits to the doctor, he was medically boarded in 2010 due to multiple chronic health problems. His last shift at the mine was on 30 October 2010, the termination form stating “Retirement”. Diagnosed with tuberculosis he was admitted to Kalafong Hospital, Pretoria, where he was successfully treated. Six months later, he returned home, ready to work again. At the request of his employers, Mncedisi obtained doctors letters testifying to his ability to resume employment. A medical examiner at Kalafong Hospital wrote, “Under controlled treatment he is fit to resume his normal duties.” The mine’s doctor at another hospital wrote, “Mr M.K. Nkotha (sic) may not be considered for any underground work. He may be considered for surface work only.” To his dismay, the mine’s Human Capital Consultant responded, “The mine is already over compliment (sic), there is no way we can consider Mr Nkotha for re-employment, if there is a labour shortage at any shaft, we ask other shafts personnel to assist, not to employ.” By 2013, Mncedisi was still without employment. Mncedisi died from a stroke on 9 November 2014, at age 62. Nokhwezi says, “What makes my husband pass away is the stress and trauma of not working because he was thinking of his children.” Nokhwezi had hoped her son would step into his father’s shoes, but was told they no longer replace the deceased with their children. With very little in compensation for her husband’s death, and nowhere to house her family, she now faces eviction. Attempts at forced removal have seen her furniture strewn on the street, but Nokhwezi refuses to leave the hostel. With the help of several families in a similar predicament they have acquired the services of a lawyer fighting to protect their right to live here.

South Africa is the world’s largest producer of platinum group minerals and profits from platinum extraction now contribute more to the nation’s GDP than gold and diamonds combined. Many learned of the extent and nature of platinum extraction in South Africa through media coverage that followed the events of the Marikana Massacre in August of 2012 in which 34 miners were shot by police during protests at a Anglo Platinum’s Lonmin mine. In addition to news outlets, photographers such as Jason Larkin, Greg Marinovich, and Thabiso Sekgala produced bodies of work that explored the aftermath of the shootings. Through his planned exploration of platinum industry impacts across the country Godfrey hoped to bring something new to the discussion on the issues raised in the coverage of the Marikana Massacre.

With support from the Open Society Foundation in Cape Town Godfrey began a year of traveling back and forth to the three limbs that make up the 50,000 sq km “platinum belt” in northeastern South Africa. His trips would begin in the western limb and take him up through the Northern and Eastern limbs into rural villages and towns. During these visits he would meet with individuals and communities impacted by the mines: herders who lost cattle from poisoned water, whole villages relocated to accommodate mine expansions, nurses who saw sharp rises in rates of HIV/AIDS infection, mine workers from local communities, and families who lost children in traffic accidents with mine trucks. “I wanted to listen to the communities I met and hear their stories,” Godfrey says, “I would ask, why have I met you today? What is your message and what is the story that you want to tell? What is your relationship with the mine? I would record everything, hours of conversation, and from all that information I’d compile extended stories.”

The texts generated from Godfrey’s conversations with individuals and communities form a key part of the final Platinum Belt series, which exists now as an online platform. The interactive website lands on a map of South Africa with the three limbs of the platinum region shaded and marked with pins. Each pin corresponds to a single village and links to a page of photographs and narrative accounts from residents and their connection to a nearby mine. The idea to recreate the platinum belt in a digital format for people to engage and interact with was how Godfrey initially envisioned the series. He wanted the viewer to understand — visually — what the platinum belt is: where are these people living in proximity to the mine? How are they directly impacted by that space? The online space also allowed Godfrey to create an archive of individual stories about the mines that could be used as a tool by participants. “It was very important to me that there was some sort of link that [participants] could share with their colleagues,” he says, “it was important that my collaborators could say “these are the stories that we shared with Ilan and we are now sharing with you because we want to tell you how we are affected.’”

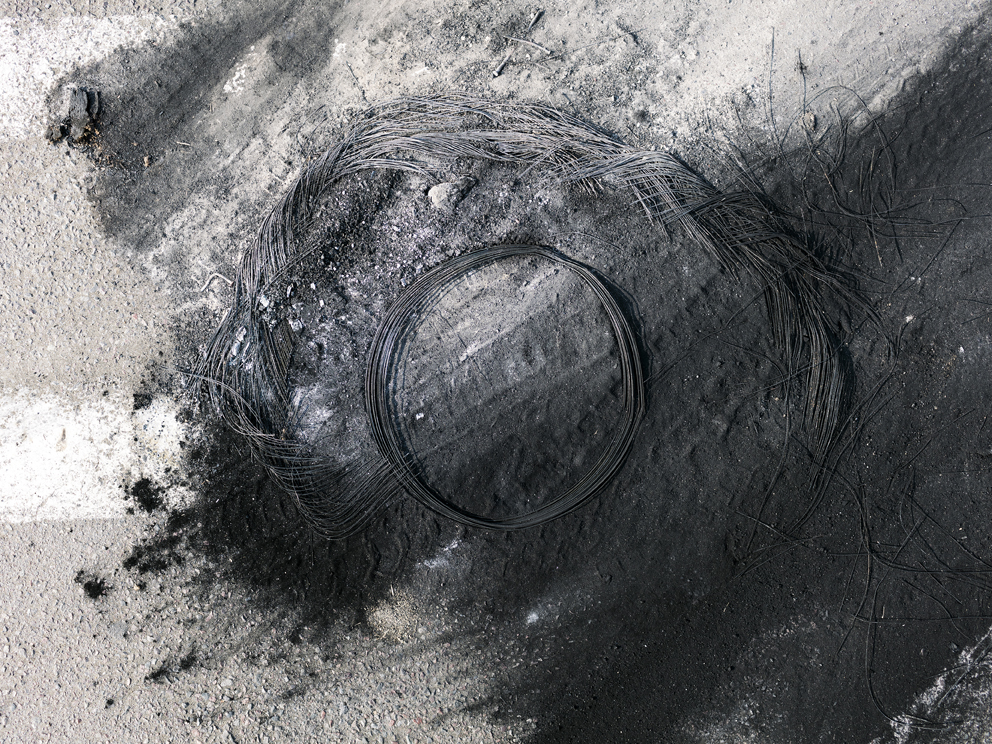

©Ilan Godfrey, Protest, 6 October 2016, Ikemeleng, Marikana, North West, Western Limb, The R104 road bears the charred remains of a community protest earlier that morning. In the twilight hours of Thursday 6 October, the smell of burning rubber and dark clouds of smoke rise above a group of men and women gathered to voice their concerns. The sprawling mining community of Ikemeleng in Kroondal, seven kilometres outside Rustenburg on the Western Limb of the platinum belt, forms the nexus of six mining companies – Lonmin, Xstrata, Samancor, Lanxess, Aquarius and Anglo American. Once the small rural farming village of the Mahermane and Baphalane people, since the establishment of these mines in the 1990s, the area has grown into an overpopulated informal settlement. Ikemeleng remains a flashpoint for people seeking employment and a better way of life, many journeying at great risk from all over Africa in search of financial opportunities. Yet in an already congested area that continues to grow rapidly, problems are also multiplying. Besides a lack of basic services, substance abuse, HIV/Aids and other STDs, rape, underage pregnancy and xenophobia are all rife, while the overbearing pressure of unemployment brings with it sex work and crime. Historically, protest in South Africa has been a formidable tool in the fight for change – a collective voice heard by all. This is certainly the case in the mining sector, where the disruption of mining and municipal operations by people from communities like Ikemeleng has become commonplace.

The Platinum Belt site confronts the viewer with the enormity of the platinum industry and the scale of its impacts on local communities. Each move between individual pages takes the viewer back to the overview of the three limbs and reminds them that each detailed count is only one of hundred other voices marked on the landscape. On the individual pages a map of specific area marked with two pins — one for the mine and one for the village — precedes any text or photograph. The move between national to local scales immerses the viewer into the single accounts and creates a geographic framework for their interpretations.

Godfrey’s online platform thus represents something of a departure from both his early work and other mining-related projects created by documentary photographers and other artists in South Africa, which have tended to follow a single or small set of place-based narratives. In Godfrey’s online platform he creates an environment for viewing the work that is different from a gallery or printed publication. The viewer cannot flip between images taken at different sites or collapse a single account into that of another village. At times it can feel overwhelming to navigate, but in some ways this seems to be Godfrey’s point: to understand the complexities of a region shaped by the platinum industry you have to immerse yourself and move in to hear first-hand accounts individually if you’re to understand the message of the whole community.

©Ilan Godfrey, Otto Lekalakala, 67, Bapong, Newtown section, North West, Western Limb a. Bapong, a sprawling village with a population of approximately 40 000, is the epicentre of the Bapo Ba Mogale royal community. The Bapo people first settled here around 200 years ago on land that holds some of the richest platinum deposits in the world. Lonmin was established here in 1970 on the basis of a lease agreement to pay the community royalties on the minerals extracted. Otto arrived in Bapong in 1989, working at the now-closed Newman Shaft for eleven years as an underground rigger, before moving to the “change house”, where he saw out the remainder of his working years. b. Now a pensioner, Otto is an active representative and concerned resident of Bapong’s Newtown section. In 2015, he was summoned to the royal palace, shortly after presenting a letter he had signed on behalf of the community pertaining to various grievances. These grievances included Newtown councillors not performing their duties, lack of employment opportunities, and members of the tribal authority not participating in meetings with the chiefs to hear the community’s concerns. Adding to the general air of dissatisfaction among the community, a controversial R664m equity deal had recently been signed between Lonmin and the royal council, which would see mineral royalties converted into company shares. Otto was among those who voiced dissatisfaction with the agreement, believing the community would not benefit. This, he believes, also strained his relations with the royal palace. On his arrival, Otto stood before a chamber of more than 100 people who quizzed him on the grievances contained in his letter. Upon insisting they speak directly to the community about them, Otto claims senior members of the Bapo Ba Mogale Tribal Authority proceeded to beat him. A friend later took him to a local clinic, where he was treated for a fractured left hand and contusions to his body. Otto says he went with witnesses to the meeting who have refused to testify about the beating, who he says were bribed to keep quiet. He breaks down in tears as he reveals that family members working at the royal palace were present but didn’t intervene when he was attacked. He opened a case at Mooinooi police station, but nothing has come of it. “I have reopened my case several times, and every time I go back, they say my case has been dropped and nobody is going to jail.” His daughter has since left Bapong for fear of reprisals, but for now, Otto is staying put. c. Community members claim that voicing concerns or gathering in groups of more than five to discuss community issues is restricted, and that even elderly people have been beaten and are afraid to testify and open cases. They say that in December, food parcels are given out to the people of Bapong as Christmas gifts, and those that speak out against the royal palace don’t receive them. Meanwhile, Otto’s injuries continue to give him pain and discomfort, and disturb his sleep. He says he has lost hope, yet he remains defiant. “They can do whatever they want with me, I don’t care because I know I didn’t fault anybody, even if they can kill me, it’s okay.”

Ilan Godfrey was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1980. At nineteen he moved to London, England where he gained a BA (Hons) degree in Photography from the University of Westminster and an MA degree in Photojournalism. Godfrey spent eleven years working between Johannesburg and London before returning to South Africa in 2011 to focus on several long-term projects, including the Legacy of the Mine, an in-depth profile of the mining industry and its impacts in South Africa. Godfrey was awarded the prestigious Ernest Cole Award in 2012 to develop and complete this project, which resulted in his first monograph and a series of solo exhibitions across South Africa. Godfrey collaborates with institutions and organisations worldwide and has been recognised by various photography awards and grants, including OSF-SA (Grantee 2016), POPCAP ’14 Prize Africa (winner 2014), the Leica Oskar Barnack Award (finalist, 2014), the OPEN Photo Award (winner, 2012), and the Magenta Flash Forward Award (winner 2007 and 2008) among others. His photographs have been exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, Wits Art Museum in Johannesburg and Musée du quai Branly in Paris. His photographs have also been featured in a broad range of leading international publications, including the New Yorker.

©Ilan Godfrey, Jane Mogotlwa, 49, Motlhotlo Village, Mapela, Limpopo, Northern Limb Jane still holds onto what is left of her homestead in the Motlhotlo Village. She has lived here her whole life and is one of a small number of remaining families under increasing pressure to relocate and make way for the rapidly expanding RPM Mogalakwena Section Platinum Mine’s northern open pit. The old Motlhotlo village was once made up of two villages, Ga-Puka and Ga-Sekhaolelo. In 1998, Amplats began negotiations with the Mapela Tribal Authority, under the leadership of the Kgoshigadi Atalia Thabantsi Langa, with a view to relocate the two communities. Relocation Steering Committees were formed and Section 21 companies brought on board to assist in the relocation process, with the relocation finally commencing in May 2007, as families were relocated to Armoede and Rooibokfontein. Some, like Jane, opted to remain in their ancestral homes. That decision has come at a cost. Every day, these families that hinder the expansion of the mine’s northern open pit are burdened with the unyielding roar of mine trucks as they dump rubble and rock several metres from their homes. They watch as mountains of mine waist slowly converge on what is left of their land. Jane is concerned about the impact her current living conditions have had on the health of her family, and believes the noise and dust have inflicted irreparable damage to her eyes, ears and lungs. With no ploughing fields and no regular supply of water, she knows she will soon be faced with the prospect of having to move. She stands firm, however, refusing to relocate until her family are offered quality housing – including the title deeds to their new home and land. She also wants surety her child will be given a job on the mine.

The Platinum Belt

Spanning several years of research and groundwork, my initial exploration of the mining sector in South Africa culminated in a body of work between 2011 and 2013 examining the minerals that have directly shaped South Africa’s socio-economic landscape. I was originally drawn to the way in which mining stamped its mark on the environment, but my experiences soon exposed something deeper: land rendered unfit for agricultural use; a public health crisis within local communities ill-equipped to cope with mining-generated air-, land- and water-pollution; and the disruptive influence of systematic labour exploitation on traditional cultural and familial structures.

The potential for expanding this project soon revealed itself – beyond the peripheries of the city, and into the small towns and rural communities surrounding areas of both abandoned and ongoing mineral activity. Entering these spaces with little pre-existing knowledge allowed me to explore these enormous, enduring socio-economic cleavages through engaging with those most affected – and, generally, most marginalised.

![11a/b/c/d - Surface mine ventilation shafts, Marikana, North West, Western Limb 11a – Ventilation Shaft – CUC2, Marikana, North West, Western Limb Jerry Chen-Jen Tien writes in Practical Mine Ventilation Engineering: “…lack of proper ventilation often will cause lower worker efficiency and decreased productivity, increased accident rates and absenteeism… [Whereas] a well designed and properly implemented ventilation system will provide beneficial physiological and psychological side effects that enhance employee safety, comfort, health, and morale.” Providing much needed extraction of pollutants from operations deep underground (including diesel emissions, blasting fumes, radiation, dust, battery emissions, and many other contaminants), these ominous structures stand like giant lungs across the platinum belt. A relentless hum and heady smell envelops the surrounds as invisible pollutants are released day and night into the communities that share the land above ground. “This ventilation shaft is very close to us,” says Ephraim Masekgaole Mphethi of Mantjakane Village on the Eastern Limb. “Immediately after a blast, the smell comes over to us – that smell, we don’t know how dangerous it is to our lives. No one is trying to monitor our lives...”](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/6_Godfrey.jpg)

©Ilan Godfrey, Surface mine ventilation shafts, Marikana, North West, Western Limb 11a – Ventilation Shaft – CUC2, Marikana, North West, Western Limb Jerry Chen-Jen Tien writes in Practical Mine Ventilation Engineering: “…lack of proper ventilation often will cause lower worker efficiency and decreased productivity, increased accident rates and absenteeism… [Whereas] a well designed and properly implemented ventilation system will provide beneficial physiological and psychological side effects that enhance employee safety, comfort, health, and morale.” Providing much needed extraction of pollutants from operations deep underground (including diesel emissions, blasting fumes, radiation, dust, battery emissions, and many other contaminants), these ominous structures stand like giant lungs across the platinum belt. A relentless hum and heady smell envelops the surrounds as invisible pollutants are released day and night into the communities that share the land above ground. “This ventilation shaft is very close to us,” says Ephraim Masekgaole Mphethi of Mantjakane Village on the Eastern Limb. “Immediately after a blast, the smell comes over to us – that smell, we don’t know how dangerous it is to our lives. No one is trying to monitor our lives…”

The work I produced during this time shone a light on everything that is wrong with the mining sector. Acting as a visual archive – a record of current mining practices and a graphic testimony to the need to find ways to reshape this rapidly growing industry – my photographs became visual signifiers for change. It is important to emphasise that the inspiration for choosing my subjects and the spaces in which I work is not statistical or scientific data. Rather, it is the product of personal experience; of my own ongoing investigation into, and knowledge gained through my travels across, the diverse and varied landscapes directly impacted by mining.

South Africa has been associated with mineral wealth, both in terms of diversity and abundance, for more than a century. In recent years, the demand for platinum in particular, of which South Africa holds the majority of the world’s reserves, has grown exponentially. But South Africa’s platinum mining industry has also attracted attention for all the wrong reasons. The tragic events that unfolded between 11th and 16th August 2012 at Anglo Platinum’s Lonmin Mine in Marikana in the North West Province resulted in the deaths of 44 people, 34 of whom were protesting miners gunned down by the South African police. A further 70 people were injured, and approximately 250 people arrested in the aftermath. These events sent shockwaves not just throughout South Africa but across the world, drawing international condemnation, igniting global discussion on, and questioning of, mining practices locally and abroad, and leading to a national commission of inquiry that lasted 300 days.

©Ilan Godfrey, Jankie Mathebula, 18 and Solly Machoga, 19, Hans Village, Mapela, Limpopo, Northern Limb Jankie and Solly welcome mining to the area as it has provided employment for their parents. Hans Village has not yet been affected by mining operations, though prospecting has commenced nearby.

With the support of a grant from the Open Society Foundation for South Africa, I returned to the north of the country in early 2016 with the aim of building on previous projects concerned with transparency and accountability in South Africa’s extractive sector, and to raise further awareness of the wide-ranging impact of platinum mining. The photographic narrative that resulted constitutes an in-depth investigation into the human, social, environmental, economic and health costs of platinum mining, documenting the communities that have grown among and straddle the northern, eastern and western limbs that make up the “platinum belt” or “Bushveld Complex”.

With the help of an extensive network of environmental activists and community leaders directly affected by platinum mining, I was able to engage with the community on various personal and emotional issues affecting their daily lives. By tracing the difficulties and dilemmas and human dramas that emerged wherever the mines of the platinum belt collided with the towns, villages, informal settlements and rural communities in their path, I began to create a body of work that connected people from different provinces across this vast mineral-rich geological outcrop.

Through my investigative fieldwork, questions are raised and directed at the platinum mining industry, and in particular, at the multitude of platinum mining companies (both multinational firms and South African black-owned empowerment companies) operating in the Bushveld Complex – an area spanning three provinces, from the North West Province across the Limpopo Province to the Mpumalanga Province; covering more than 50 000 square kilometres; and home to 80 percent of the world’s known platinum reserves.

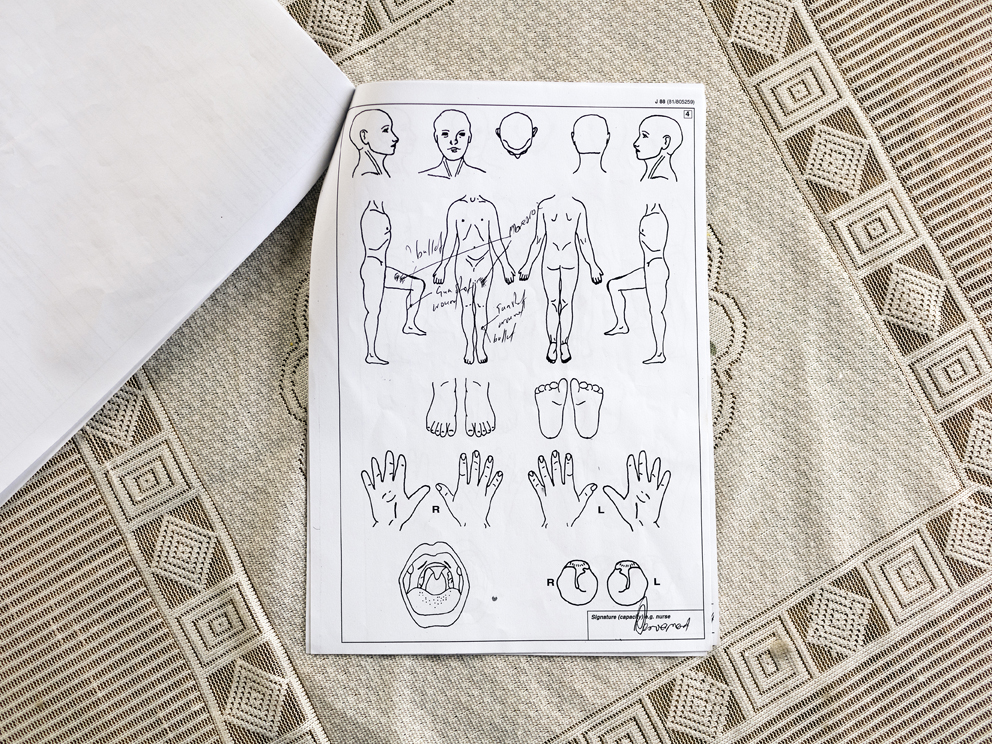

©Ilan Godfrey, Police Report illustrating Nthnabiseng Florence Mputla’s gun shot wound, Ga-Molekane Village, Mapela, Limpopo, Northern Limb

©Ilan Godfrey, A young boy herds cattle adjacent to RPM Mogalakwena Mine’s tailings dam, Ga-Molekane Village, Mapela, Limpopo, Northern Limb William Nkuna, 51, the head herdsman employed by the community of Ga-Molekane to supervise the safe grazing of livestock in the area, recalls a time when cattle could roam as far as the mountains of Mohlohlo. “When we were growing up here there was plenty of grazing land. Now the mine has taken that all away. We had land to farm, land to live. Now we have nothing.” Due to the increasing pressure to feed his livestock and the ongoing financial constraints on William and his family, he has sold off 15 head of cattle in recent times to give his child the chance to go to school.

Worldwide, demand for platinum is increasing, driven mainly by its use in catalytic converters in car exhausts and in the jewellery industry. Platinum has also become an important component in some of the new emerging technologies. Indeed, the scale of platinum mining activities planned for the future could make Limpopo the richest province in South Africa. In the North West province, too, mining is responsible for more than a third of the region’s gross domestic product, with the Rustenburg and Brits districts in particular producing more platinum than any other area in the world.

But as important as platinum continues to be as a driver of economic growth in South Africa, the human cost has been extraordinary. All across the platinum belt, as the mining companies seek out the mineral in huge open cast mines, the communities that live in their path are forcibly displaced, and often thrust into a completely unsustainable situation, with insufficient land to live on and none of the employment opportunities they were promised.

©Ilan Godfrey, William Nkuna, 51, head herdsman in the community of Ga-Molekane Village, Mapela, Limpopo, Northern Limb

The mining industry is a microcosm of the overall picture in South Africa, which has enjoyed moderate economic growth while the divisions of the past – between rich and poor, white and black, remain entrenched. The environmental and social costs of mining are considerable, and the benefits that the mines bring are not always equitably shared, while local communities closest to the source of the mineral development suffer the most. Communities that come to depend on the mines for economic survival after having their subsistence farming literally taken from under their feet are especially vulnerable. Their fate forcibly tied to that of the mine, a mine closure spells instant disaster.

I hope that this body of work continues to ignite discussion around how as a society we need to stand together in bringing about a broader understanding of our shared resources and how best to use them. We need to acknowledge the fragility of the environment and the vulnerabilities of the people that live on the land under which the minerals are found. Growth and development is a prerequisite for economic stability yet we must never forget the wider context – how we got here, and how we should move forward into a sustainable and equitable future, where all facets and factors and peoples are considered. – Ilan Godfrey

©Ilan Godfrey, Mishack Mampuru, 68, currently owns 15 head of cattle – 5 dead, 1 miscarriage Herdsmen from the Morapaneng, Dithabaneng and Ditwebeleng communities are concerned for the safety and wellbeing of their livestock. Since the arrival of mining operations in the area, they have seen a steady deterioration in the health of their cattle, with death and miscarriage an ongoing concern. “We used to enjoy plentiful grazing land and clean drinking water – there were no problems,” muses Thobajane M Phineas, 55, from Morapaneng, recalling the pre-mining days. “But immediately after they started to mine, fences were erected and roads were laid, destroying trees that our animals relied on for shelter during times of sunshine and rain.” The herdsmen believe the main source of their woes is what appears to be a polluted stream that flows from Twickenham Platinum Mine’s Hackney Shaft. Channelled by muddy banks well-trodden by cattle hooves, this lifeless body of water flows into the nearby Motse River. A once thriving and powerful tributary that provided much-needed drinking water to man and beast alike across the Sekhukhune region is today no more than a small, murky rivulet. Salt deposits line the rocks in the shallows as people eke out small quantities of sulphate-laden water for cooking and drinking. Thobejane and his fellow herdsmen have no other choice but to accept that platinum mining on their land is here to stay. “We ask if the mine can build us a camp where we can kraal our cattle, give them a safe place to stay and provide containers of clean drinking water so they never again drink the water flowing from the mine.” Thobejane sighs, “We are sick like the cattle”. He is uncertain what the future holds. But he knows their lives and livelihoods are at great risk.

©Ilan Godfrey, Tshepo Highlight Khoza, 39, AMCU Worker Organiser, Monametsi Village, Monametsane Section, Limpopo, Eastern Limb a. Passionate and outspoken, espousing views that some might deem controversial, Tshepo, 39, is a self-described AMCU “worker organiser” at a platinum mine in the area. When the Marikana strikes erupted in August 2012 on the Western Limb near Rustenburg, the air of unrest spread across the platinum belt, with mining communities as far as the Northern and Eastern Limb taking up protest action of their own. Feeling compelled to show solidarity with his comrades and fellow miners, Tshepo helped transport AMCU committee members to the unfolding strikes that had already taken the lives of several striking miners, police and security personnel. He believes this is what may have led mine officials into thinking he was a threat to mining operations. b. A few months later, on his arrival at work, Tshepo says that he was seized by mine security and paraded as a criminal and enemy of the mine. In a state of bewilderment, Tshepo assured them he held no mining property in his possession. Mine security and HR personnel proceeded to question Tshepo about the guns and explosives allegedly in his possession that were stolen in 2012 at Marikana and were to be used in an attack on the mine. He protested his innocence to no avail, as police waiting outside the gates took him into custody. After searching his vehicle and finding nothing, they drove to his home, where his wife and three-month-old child were resting. Tshepo describes how they “barged in” and how “with my hands tied, they beat me”. Dogs and police searched top to bottom. Again, no guns or explosives were found, but they did find marijuana and alcohol. Tshepo was taken to the mine barracks where he was choked and forced to write a letter stating his plans to bomb the mine. He was threatened with arrest for possession of marijuana – a charge he was willing to accept – but refused to sign the letter. Soon after the incident, Tshepo opened a case against the officers, but nearly four years later, no charges have been brought against them. Indeed, in 2016 police and mine security targeted his home once again, this time damaging property and beating a tenant who was renting a room in the house. No explanation was given as to why they were there or what they wanted.

©Ilan Godfrey, Eustina Matsepane, 34, Modimolle Village, Limpopo, Eastern Limb a. Childhood sweethearts Eustina Matsepane and Joseph Kapudi Mampuru grew up on the same street in the small rural village of Modimolle. By 1997, Eustina, 15 at the time, and Joseph, 18, decided they were going to share their lives together, and the following year they welcomed their first child, Thabang Actavia Matsepane, into the world. Soon after, Anglo Platinum established the Twickenham Platinum Mine in the area, and Joseph, an electrician by trade, sought employment on the mine. The couple saw in the mine an opportunity to make a better life for themselves, and provide for their growing child. b. Regrettably it was not to be. Employment opportunities remained scarce in the community even after mining had been in operation for a number of years. People from the surrounding villages felt frustrated that the mine had encroached on their land without giving them much in the way of reciprocal benefits. In September 2013, they marched on Twickenham Platinum Mine. Their objective was to deliver a memorandum to mine management, listing their grievances and calling for more employment oppurtunities. c. Eustina remembers the day clearly. “The police arrived and said we must stop what we are doing. It was at that moment teargas was fired into the crowd.” Panic ensued, the crowd began to disperse, everyone running in different directions. Losing his partner in all the confusion, Joseph found himself struggling to breathe. He had inhaled teargas and began to vomit. A friend helped him to his mother’s house where he continued to vomit violently. Those gathered round him soon realised he was in a critical state and arranged for a vehicle to take him to Mecklenburg Hospital. Sadly Joseph would never make it to the hospital – he passed away in the back seat of the car. “I felt so much pain during that time,” Eustina recalls, though her voice is steady. “Even now my son has no one to look after him, his father used to look after him but now I am stranded.”

©Ilan Godfrey, Power cables, Modimolle Village, Limpopo, Eastern Limb, Much needed rain floods the low-lying land that surrounds the power lines supplying electricity to Anglo Platinum’s Hackney and Twickenham Shaft. The strategically positioned cables and adjacent tar road cut through the Merensky and UG2 Reef outcrop, hampering farming activities in the area. Twickenham Platinum Mine is established on the Twickenham, Paschaskraal and Hackney farms on the Eastern Limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex in the Northern Province. At current planned production rates, the mine’s resource base is sufficient to sustain production for more than 30 years. “At full production some 2200 people will be employed on the mine,” read a statement announcing the establishment of the mine on 6 September 2001. “Apart from the direct benefits that will flow from this employment… the mine will create opportunities for other economic and small business development in the area.”

©Ilan Godfrey, Youth without employment, Maphanga Supermarket, Mantjakane Village, Limpopo, Eastern Limb

©Ilan Godfrey, Water-filled open cast pit, Phashaskraal Mosotsi Village, Limpopo, Eastern Limb In the early summer heat, young children from the Phashaskraal Mosotsi Village are drawn to the tranquil waters of a nearby abandoned open cast pit owned by Bokoni Platinum Mine (and operated by subcontractor Benhaus Mining), in which an inviting pool of water has collected. It was here that tragic events unfolded on Monday, 31 October 2016 when Kamogelo Makgopa, 15, sadly drowned. A short walk from the community, the site has been unfenced and unmanned since operations ceased a number of years ago following the death of a resident of the same village who was struck by a rock during blasting. The community remains troubled by the loss of life that has beset them since mining operations began, and describe how only after the drowning, a small fence was swiftly erected around the open cast pit.

©Ilan Godfrey, Sefiti Johannes Makgopa, 48, Monametsi Village, Tipeng Section, Limpopo, Eastern Limb Sefiti, 48, born in Monametsi Village, has lived in the shadow of the mines for most of his life. In 1995, he began work as a winch operator at Bekoni Platinum Mine’s UM2 vertical shaft, where he would remain for the next 16 years. Sefiti was skilled in his operation of the winch, but in 2011, a split-second occurrence resulting from the smallest oversight saw his hand wrenched from his arm and his life left in ruins. In the intervening years the healing process has been slow. Pain and discomfort, and at times, depression, have plagued him. Sefiti remains frustrated and angry at what happened. His treatment at the hands of his employers hasn’t helped, and he is particularly saddened that no mine personnel ever came to visit him in hospital. “The problem with the mine,” he says, “is they don’t care about their workers, they only want you if you are physically strong. Once injured or crippled they don’t care about you.” After receiving a letter terminating his employment, Sefiti approached the CCMA, who took up his case, and won an agreement from the mine that they would keep paying him a monthly salary up until retirement. Sefiti is currently in training for another job at the mine that involves, among other activities, packing overalls.

©Ilan Godfrey, Phindile Sekome, 23, Ga-Kgwete Village, Limpopo, Eastern Limb With the global platinum market surging in recent years, the Greater Tubatse Local Municipality has prioritised the development of the platinum-rich Dilokong Corridor, with a view to generating infrastructure investment, job creation and other economic opportunities for communities in the region. Phindile Sekome, 23, who shares a small homestead with her grandmother and younger sisters in the Dilokong Corridor in the village of Ga-Kgwete, welcomes development in the area, but not to the detriment of her home or her family’s wellbeing. In 2004, Lebalelo Water Association were contracted by government to lay approximately 180kms of pipeline for the supply of raw water to mining operations in the area. One of these underground pipes would run adjacent to the homes of five families in the Ga-Kgwete Village, among them, Phindile’s grandmother’s homestead. Phindile recalls how explosives were used to break through the rocky ground, resulting in irreparable damage to property in the vicinity. Burdened with having to patch up the crack-riddled walls, the affected families voiced their grievances to local leadership and the company responsible. After years of gridlock, negotiations with Labelelo Water Association finally began in 2016, with the successful construction of five new homes that same year. Although Phindile is grateful for their new home, she remains unsettled. Questions persist as to whether the new home built on her grandmother’s land is legally theirs. With no documents to prove this and her grandmother’s current frail state, she worries where, after her passing, they will live if forced to move. And thirteen years since an extensive network of water-carrying pipeline was laid under her feet, Phindile continues to collect the family’s daily supply of water from the communal borehole several metres behind their home.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026