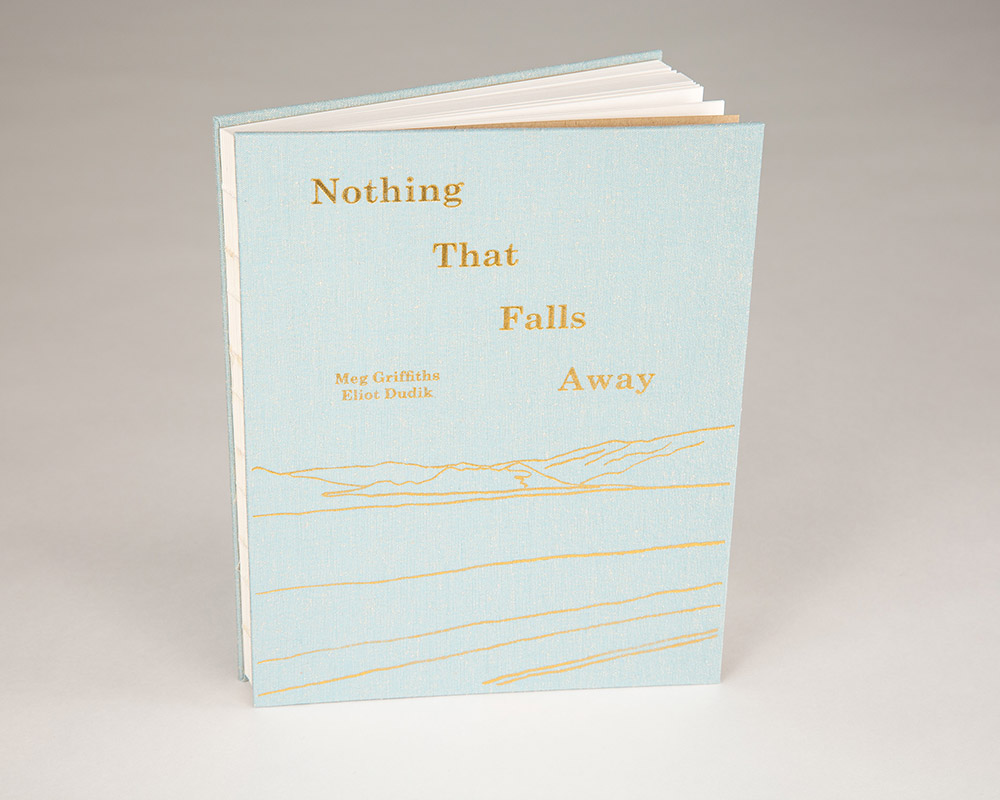

Nothing That Falls Away: A Conversation with Eliot Dudik and Meg Griffiths

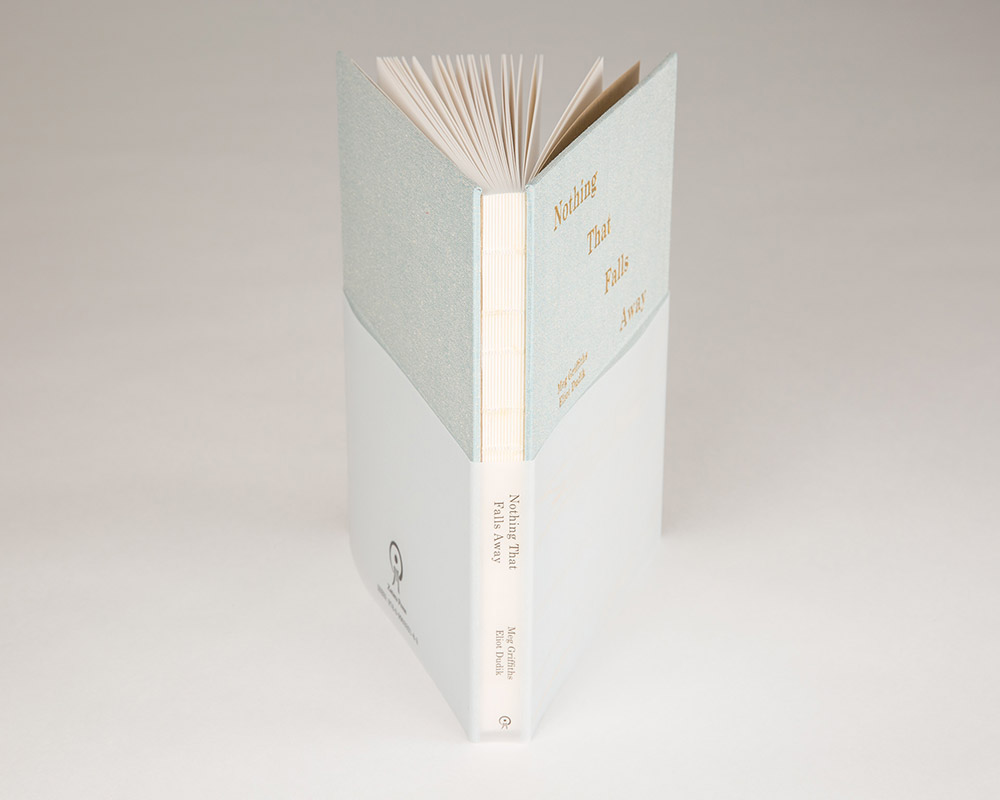

Before the New Year, I had the distinct honor of hosting a conversation with artists Meg Griffiths and Eliot Dudik on their newest joint book project, Nothing That Falls Away, published with Zatara Press. This book is a collaboration in every sense of the word. As they transit across the remote Nevada landscape along Highway 50, coined by LIFE as “the loneliest road in America”, Griffiths and Dudik seek to call into question how we find our way when relationships and lives change course. Now that we’ve entered a new year, full of unpredictability and things unknown, I don’t believe there could be a more perfect time to contemplate this lyrical and poetic work.

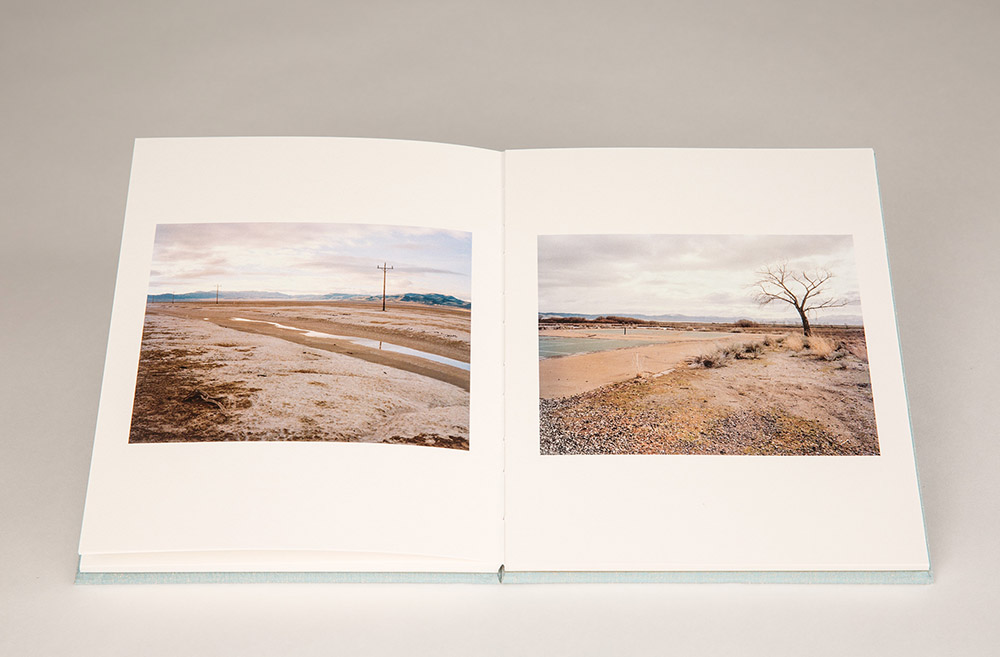

© Meg Griffiths & Eliot Dudik

Meg Griffiths is a Texas based artist and educator. Her photographic research currently deals with domestic, historical and cultural relationships across the Southern United States and Cuba. Her work has been shown internationally, including: PhotoZurich Germany, Barcelona Biennial for Fine Art and Documentary Photography, Pingyao International Festival of Photography, Chaing Mai Photo Festival, at venues within the United States such as Columbia Museum of Art, Center for Fine Art Photography, Museum of Living Artists in San Diego, Griffin Museum in Boston, Houston Center for Photography, Candela Gallery in Richmond. She was recently published on the cover of Focal Plane Journal as well as the cover of Oxford American in 2018. Her work is a part of many private collections as well as the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Center for Fine Art Photography, Middle Tennessee University, and the Capitol One Collection. Her first monograph Casa de fruta y pan was published in 2015, and most recently she published two collaborative projects, Nothing that Falls Away with fellow photographer Eliot Dudik through Zatara Press, and a 52 person collaboration published with One Day Projects called “And light followed the flight of sound.” By virtue of recognition these books have been collected by institutions across the country such as MOMA, Museum of Fine Art, Houston, Duke Archive of Documentary Art, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art as an example. Meg was recently honored to receive the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for Best Fine Art Series in 2017, selected as on of Atlanta Celebrates Photography’s One’s to watch in 2016, honored as the second place winner of the PhotoNOLA portfolio Prize in 2015, and named one of PDN 30’s: New and Emerging Photographers in 2012.

Photographs and books by Eliot Dudik are found in institutional and private collections across the globe. His work explores the connection between culture, memory, history, and place. His first monograph, ROAD ENDS IN WATER, was published in 2010. In 2012, Dudik was named one of PDN’s 30 New and Emerging Photographers to Watch and one of Oxford American Magazine’s 100 New Superstars of Southern Art. He was awarded the PhotoNOLA Review Prize in 2014 for his BROKEN LAND and STILL LIVES portfolio, resulting in a book publication and solo exhibition. His unique and interactive book COUNTRY MADE OF DIRT (2017) was recently acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Dudik produced two collaborative books in 2018: NOTHING THAT FALLS AWAY with Meg Griffiths and Zatara Press and AND LIGHT FOLLOWED THE FLIGHT OF SOUND with Jared Ragland for One Day Projects. Dudik’s work will be included in the Mulhouse Biennial of Photography at the French Cultural Center in Freiburg, Germany during the summer of 2018. Dudik’s photographs have been published in Smithsonian Magazine, New York Times, CNN, Oxford American Magazine, as well as featured in Lenscratch, View Camera Magazine, Rangefinder Magazine, Photo District News (PDN), Hotshoe International, Feature Shoot, BuzzFeed, The Great Leap Sideways, Guide to Unique Photography (GUP) Magazine, and VICE. His photographs have been installed internationally in solo and group exhibitions including the Griffin Museum of Photography, Center for Fine Art Photography, Dishman Art Museum, Morris Museum of Art, Masur Museum of Art, Muscarelle Museum of Art, Cassilhaus, Annenberg Space for Photography, Columbia Museum of Art, Southeast Museum of Photography, the Chiang Mai Photo Festival, the Southern Gallery of Contemporary Art, Gordon Art Galleries at Old Dominion University, Welch Gallery at Georgia State University, Rebecca Randall Bryan Gallery at Coastal Carolina University, Staniar Gallery at Washington and Lee University, Warner Gallery at St. Andrew’s School, New Orleans Photo Alliance, Carte Blanche Gallery, Davis Gallery at the Mayo Clinic, and the Carlson Gallery at the University of La Verne. Dudik taught photography at the University of South Carolina from 2011 to 2014 before founding the photography program within the Department of Art & Art History at the College of William & Mary where he is currently teaching.

© Meg Griffiths & Eliot Dudik

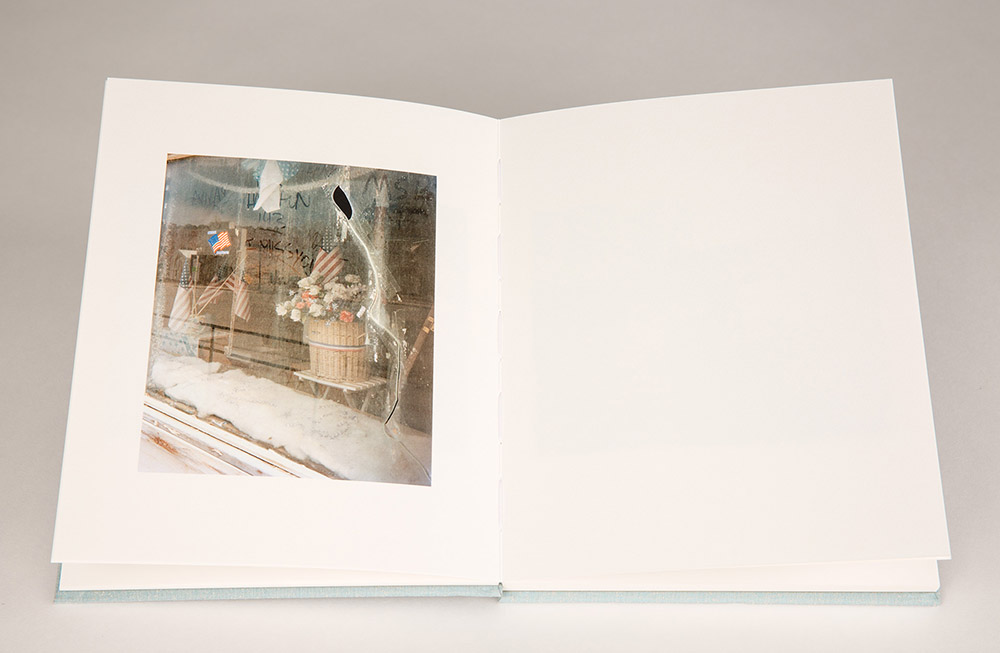

In Nothing That Falls Away photographers Meg Griffiths and Eliot Dudik present a collaborative series of color photographs representing a psychological and physical exploration of the landscape traveling across Highway 50, a two-lane road which bisects the state of Nevada. Established along The Pony Express and coined in 1986 by Life magazine as “The Loneliest Road in America,” Highway 50 is known for traversing a desolate and sparsely populated stretch of seemingly barren country. Along this road, Griffiths and Dudik explore love and loss, longing and wanderlust—those spaces we inhabit where things are often unclear. Through imagery and poetic prose, they poignantly direct our attention to the complication of personal relationships, the yearning for connection and the desire for autonomy at a moment of intersection in their individual lives.

Julia Bennett: For those who may not know, do you want to talk about how it was that this book came to be? This is the first time you’ve published photographs together in such a collaborative forum, yes?

Eliot Dudik: I think I’ve considered us collaborators since we met back in 2009, but yes, this book represents the most solidified form of our joint artistic efforts.

Meg Griffiths: I agree, I think we have always supported one another– as artists, for a period of time as partners and now as friends. We met in graduate school, got our first academic jobs at the same place, and in many ways grew up in this field together. These things separately forge intimate bonds—but together make our relationship very unique. I too feel we have been collaborating all along, this would just be the first time we made a formal project together and put it out in the world. As for this collaboration, oh my well, this project almost didn’t happen at all. It was serendipity really. Eliot and I were originally to collaborate with two other photographers on a completely different project in a different State. Then due to various circumstances the other two were not able to go. We knew we still wanted to make pictures and we were both still committed to going, however we had to restructure where and why. After some discussion we settled on Nevada. More specifically, making pictures together along the road that bisects the state coined by Life magazine as the “Loneliest Road in America.” We were both intrigued by this for various reasons, but in general what traveling that road would mean to each of us separately, making work side by side, at this particular stage in our lives.

© Meg Griffiths & Eliot Dudik

One of the things I love most about the book is how steeped the imagery is in symbolism and memory, while visually staying true to a more familiar documentary style. On the surface it could be a documentation of a place, this lonely road and the things found along it. How did you think then, and also now, about the surrogacy of the objects and spaces you found?

MG: This project has so many layers. It is nice to hear you say that you think so and that you love this too, Julia.

Upon reflection, the work feels more holistic to me. Encompassing many narratives throughout history. It was not really until we began to think about this collaboration as a book that I started to research more about the history of the land and all those that have made their way across. It carries the weight of all these stories, both harsh and rich, and for me this is the subtext of the images. A narrative which witnesses the absenting and re-populating of culture: from the Native tribes of the Washoe which inhabited Nevada for millennia to the immigration of French, Portuguese and Chinese with the introduction of the railways system and the mining of copper, silver and gold. The images reference Nevada’s economic fluctuation, from the boom of the Great Silver Strikes in the mid 1800’s, to big busts like the 2008 economic crisis. And of course more traditionally, the work pays respects to a long-standing photographic tradition of traveling West, to the idealization of the road and the American idea of freedom being wrapped up in the car.

At the time however, what drew me to make the work was rooted in things that were quite personal and primal. There was a sense of urgency– to be autonomous, to wander and be alone, to have something of my own. I thought, naively, this might possibly be the last time I could do something like this for myself. Even to be alone with someone, traveling like this, one of my best friends. You see, at the time I was 7 months pregnant. I had this fear that in creating something else I might possibly be giving up my potency, viability, and relevance as an artist. In this act of having a child I would also give up the option of choice to be many other things in my life. I would be giving away the gift of time. So at the point of making, these were the things weighing heavy on my mind. I see all of that in this work too. What about you Eliot? How did you think then versus now?

ED: The trip came about so quickly, we didn’t have much of a plan. We didn’t set out to make photographs that would ultimately end up a sequence in a book. I think we were both aware of big shifts in each other’s lives, and were interested to see what manifested photographically through the confines of a single, straight, desolate road. There were some interesting differences in our personal lives too. As Meg mentioned, she was preparing to have her first child and spoke of her fears of never being lonely again. I was in the throws of the loneliest period in my life, one consumed by my new job and otherwise spent in my isolated studio or solo on the road. I think it’s impossible to separate these fears and circumstances from the act of photographing, and I don’t think we tried to. I believe it’s a lot like learning a new word where all of a sudden you see or hear it everywhere. When we were traveling across Nevada, our thoughts and feelings were manifesting in the landscape around us, those were the things that garnered our attention and that we ultimately composed on the ground glass. Perhaps I had an advantage here because I’m often using the land for an attempt at meaning. I’m often photographing nothing and asking it to mean something. Yet it was difficult in this space to couple what little was there, and the overwhelming similarity of the landscape, with our complicated thoughts and uncertain futures.

I love what you said about photographing nothing but asking it to mean something. I think that a place like the Loneliest Road in America is the perfect environment to project onto the landscape- especially in the winter-time. Honestly, it’s the images in this series that are of nothing but white-washed land and sky that I have the strongest emotional reaction to. It’s so interesting that the timing and location materialized so serendipitously. The book concludes in sort of a visual crescendo of open space and light that feels really complete. I’m wondering how you both feel about resolution with regard this work and also I guess more generally with regard to the process of photographing.

ED: The weather we encountered was crucially serendipitous. We were actually on the road making this work in the spring, just before the national Society for Photographic Education conference in Las Vegas. But the road stretches through vast desolate basins and then into mountains, and repeats like this for the 400 miles across central Nevada. e.g.: ___^^^________^^^________^^^________^^^ ___ and so on. Nearly every time we began the incline into the mountains we were hit with massive blizzards or rainstorms. Sometimes whiteouts came rushing across the basins toward us; sometimes they were clean and clear with visibility that seemed to go on for hundreds of miles. We were lucky to encounter such varied weather across the state, which gave us the flexibility to twist it into a meaningful progression.

I think we intentionally concluded with photographs of the most extreme whiteouts to suggest an open-ended finale, a marker for where we were at the time of photographing, but with a future ahead that is undefined. It seems to be the end of one episode, and an anxious beckoning toward the next chapter. Photographically, these images act as the most concrete memories of the trip, but the suggested narrative is designed to have no resolution.

MG: That is really so well put Eliot. It is so true! We were incredibly fortunate in a number of ways, from the serendipity of going on that trip together, to the vast and harsh terrain, to the metaphorical and tempestuous weather. I don’t think either of us had any notion exactly what would happen next. When editing and sequencing, we really wanted to invite those going through the book into this space of not knowing. There isn’t meant to be a chronology or prescribed experience. There are no titles to tell you where you are and there is no assigning authorship for who owns what image—or experience for that matter. The book is fashioned to allow for someone to come along with us, to get lost too, to be with their own stuff. It is a shared journey we are all on, even though it is quite unique to each of us. And that is why it could only ever be open at the end in terms of the images. There is just no knowing what is to come.

© Meg Griffiths & Eliot Dudik

ED: My perfect day would include no alarms, studio work in my underwear, terrific NPR programing, and ice cream.

MG: I heard a reading of a poem called Everything is Waiting for You by this amazing Irish poet named David Whyte. In it he says that “Alertness is the hidden discipline of familiarity.” It just made me think how everyday can be a perfect day with intention of awareness. So my answer I suppose is any day where I get to spend time with my son just being present. Any Friday that I get to spend half the day in the studio with attention to my craft and intuition. So, yes, in part almost everyday is my perfect day.

© Meg Griffiths & Eliot Dudik

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025