PhotoNOLA: Kiliii Yuyan: Searching for Home

©Kiliii Yuyan, Traditional whaling is practiced in tune with the unpredictable weather of the Arctic. Wind has pushed floating ice near the shorefast ice and the whalers must wait until it shifts again, sometimes weeks later.

I always review a photographer’s website before I meet with them at a portfolio review, so I was very much looking forward to meeting Kiliii Yuyan at PhotoNOLA. His desire to document indigenous cultures comes from the personal place of his own family histories, histories that allow him to enter communities with not only a photographer’s curiosity, but a compassion and desire to bear witness to and document disappearing Arctic lifestyles. For his project, Searching for Home, Kilii looks at the people and places that most parallel his own identity. “When I’m photographing, I’m living inside my grandmother’s stories.”

Photographer Kiliii Yuyan illuminates stories of the Arctic and human communities connected to the land. Informed by ancestry that is both Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous) and Chinese-American, he explores the human relationship to the natural world from different cultural perspectives. Kiliii is an award-winning contributor to National Geographic Magazine and other major publications.

©Kiliii Yuyan, This camp, erected miles out on the sea ice, is the Iñupiaq home away from home. Despite spending months living in cramped and frozen quarters, the captain of Yugu crew prefers it. “It is quiet here.” This setup is typical of spring whalers, who spend months on the sea ice waiting for whales by their skinboat.

Searching for Home

©Kiliii Yuyan, At Nalukataq in Barrow, Alaska, the Iñupiaq whaling festival, the village comes out to celebrate a successful whaling season and to give thanks to the whale for its gift. Here, successful whalers must do the blanket toss. They are thrown up to thirty feet in the air, and depend on everyone’s hands to land safely. This trust goes back millennia, and ensures intimacy among the growing population in Iñupiaq villages.

They were stories of fish bigger than canoes and our heroes riding on the backs of killer whales. As an adult I wanted to bring those stories alive and understand my culture. But there’s no going back home after a century of genocide and displacement. I’ve found myself living and working in other indigenous communities across the Arctic, the region that’s most similar to my homeland.

Searching for home is looking for the places in my culture’s stories. When I’m in Alaska or Greenland, I see the stories all around me. I’m bathed in the light of the North. I can smell scent of sealskin, and watch as umiaq skinboats float across the ocean horizon. When I’m photographing, I’m living inside my grandmother’s stories. And when I bring my pictures together to tell a story, I know that I’m carrying forward these living stories. – Kiliii Yuyan

©Kiliii Yuyan, Flora Aiken gives a silent blessing to the first bowhead whale of the spring season. The Iñupiaq have a rich spiritual life which centers around the gift of the whale to the community. Foster Simmonds offers a prayer, saying, “Hide something for me. Look at the food, the whales. Look at the sea, the whalers. A blessing for them. Take that and hide it in your heart.” The whale here is tied up after being towed to the ice’s edge and is awaiting the village to come and help haul it onto the ice.

©Kiliii Yuyan, Polar bears present an ever-present danger to Iñupiaq whalers when out on the ice. Attracted to the scent of fresh blubber, they prowl the edges of camp, but are usually scared off by rifle shots and noisemakers. During whale butchering many people stand guard against the bears circling nearby and keep children close to camp. This bear at Akootchook’s whale was one of thirteen seen in a single day on the sea ice off Utqiagviq, Alaska.

©Kiliii Yuyan, Larry Lucas Kaleak listens to the sounds of passing whales and bearded seals through a skinboat paddle in the water. The sounds of bearded seals and bowheaded whales are unique and distinctive, and can be easily heard in the vibrations of the wooden paddle.

©Kiliii Yuyan, Beluga whales migrate along the same path as Bowhead whales, in pods of hundreds. These belugas are not hunted during the Iñupiaq whaling season– there is a time and place for that.

©Kiliii Yuyan, Today’s Iñupiaq leaders live double lives, treading the fine line between modern concerns for the community and the subsistence lifestyle. Maasak Leavitt, who works for the North Slope Borough, was hurt when his son pronounced on Facebook that his dad was ‘too busy politicking’ to hunt. Maasak hopes one day his son will understand that his work in government helps to protect traditional practices.

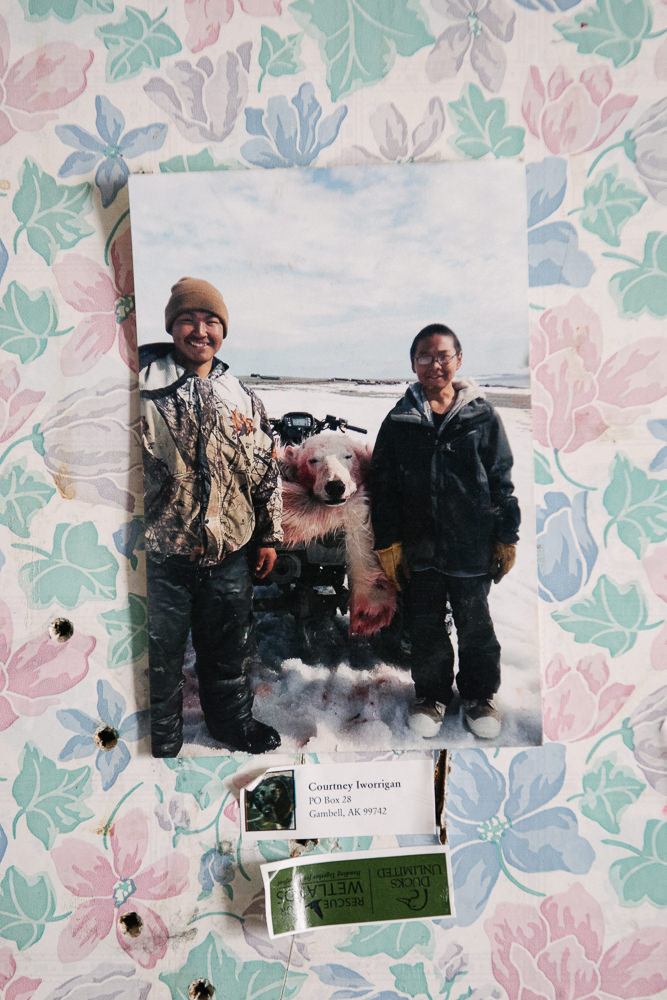

©Kiliii Yuyan, A family photograph of a rare polar bear hunt. Subsistence hunting remains a strong source of pride to the Yup’ik. One ongoing aspect of colonization is the restriction of subsistence hunting rights by non-Native lawmakers.

©Kiliii Yuyan, A large polar bear investigates the freshly butchered carcass of a bowhead whale. The scent of this whale attracted 13 polar bears in a single day, which presented considerable danger to the wary Iñupiaq whalers who nonetheless allowed the bears to feed.

©Kiliii Yuyan, A recently harvested bowhead whale rests along the edge of the ice. The last census in 2011 showed an incredible 17,000 bowhead whales in the Beaufort sea population with a healthy rate of growth. Iñupiaq knowledge of whale population and biology proved far more accurate than Western science in the 1980s and has since led to the recognition of traditional ecological knowledge.

©Kiliii Yuyan, The frame of a skinboat rests on trestles, a reminder of Yup’ik traditional culture. For the youngest generation of Yup’ik, traditional culture can be a lifeline. 16-year old Sam Schimmel from Gambell says, “What I’ve seen is that when youth are not culturally engaged, you see higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of suicide, higher rates of alcoholism, higher rates of drug abuse — all these evils that come in and take the place of culture.”

©Kiliii Yuyan, Kunuunnguaq Davidsen performs a Greenland kayak (qajaq) roll in the 2018 Greenlandic National Championships in Nuuk. Traditional kayak rolling was done to recover from capsizing during kayak-hunting. It has since evolved into a national sport with 37 increasingly difficult rolls.

©Kiliii Yuyan, On the Arctic Ocean, Iñupiat paddle their umiaq skinboat. A Fata Morgana mirage makes their umiaq appear to float over the sea. Spring whaling by umiaq is made possible by the shorefast sea ice. As the sea ice gets thinner each spring from a warming climate, traditional whaling becomes increasingly challenging.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026