On Collaboration: PWMD (Marissa Dembkoski & Paal Williams)

On Collaboration: PWMD

interview by Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman

Marissa Dembkoski and Paal Williams are the collaborative artist team PWMD. Their sensibilities come together in work that has a delicate duality. They disassemble the vocabulary of rendering and perception while simultaneously honoring it. Their images expose the construction and limitations of representation. Histories collide in assemblages where the digital lexicon is probed with precision by their large format film camera. Image>ImageSize, a recent installation at Lillstreet Art Center where Dembkoski and Williams are artists in residence, invited viewers into their spatial ambiguities. On June 15th, the artists will release The Critical Eye: Fifteen Pictures to Understand Photography, currently available for preorder on both Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

As collaborators who live in different cities, we were curious about their process and the back and forth of their collaboration.

Dembkoski and Williams received their BFA from Lesley University College of Art and Design in Photography and Art History in 2017. Their work intertwines artistic tensions from the history of photography, and contemporary modes of photographic production to question the constructs of visual culture. Upcoming exhibitions include Counterpublic 2019, at the Luminary Arts Center, St. Louis, MO.They are currently artists in residence at Lillstreet Art Center in the photography department, living and working between Chicago, IL and St. Louis, MO.

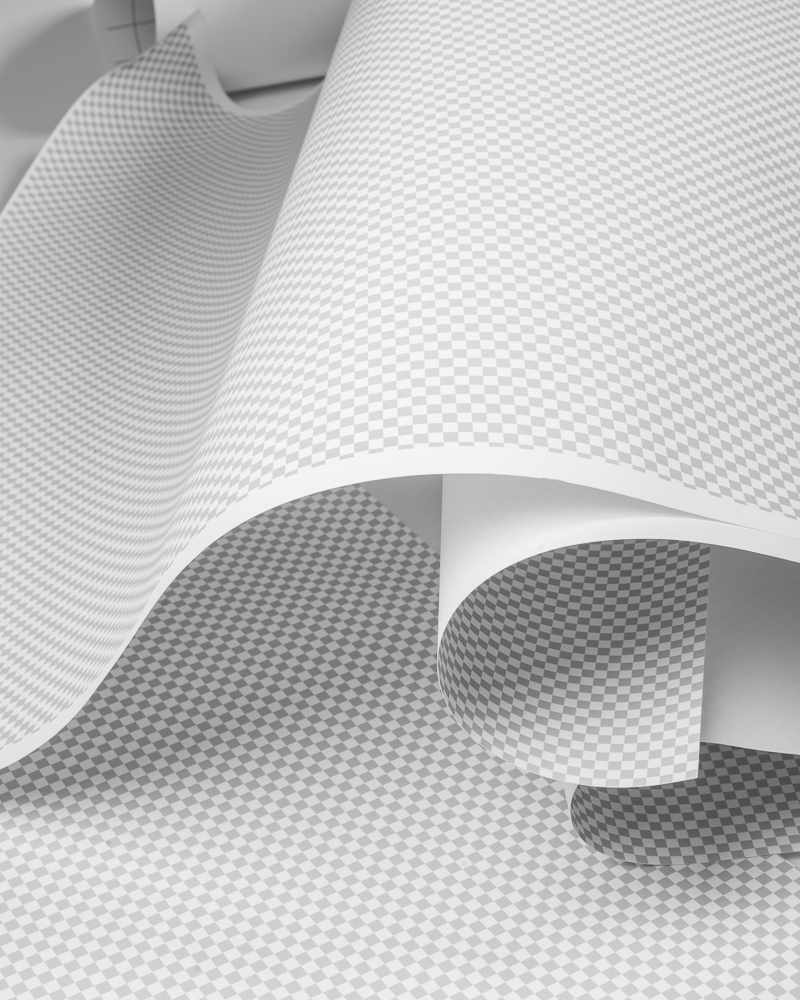

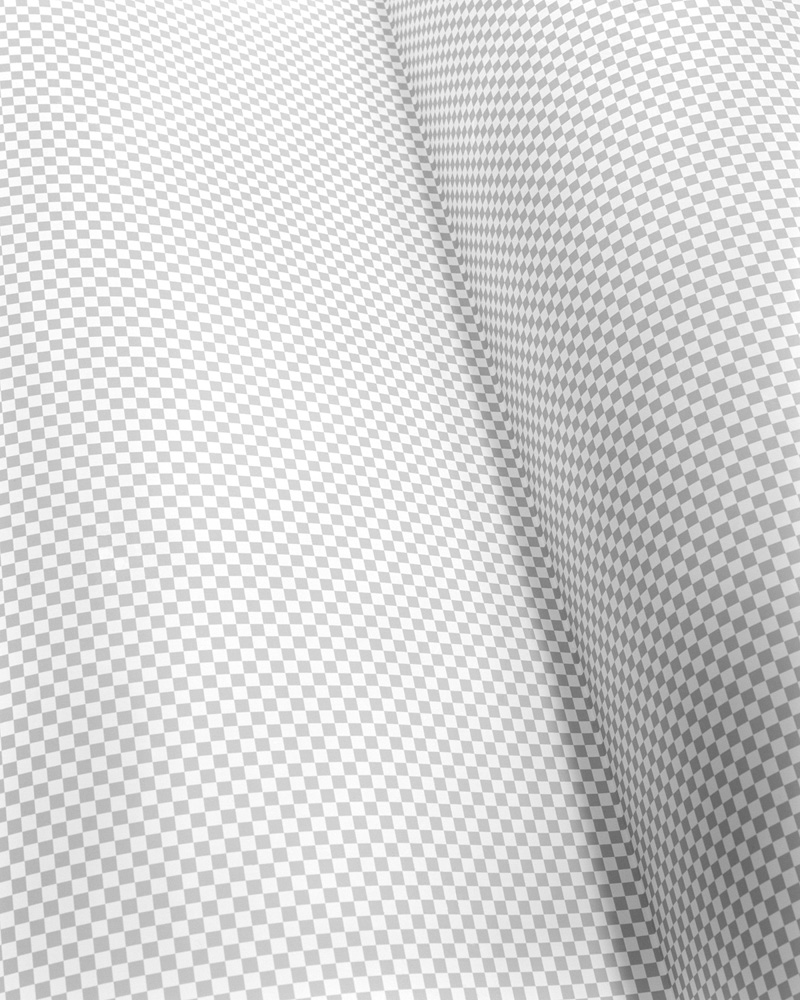

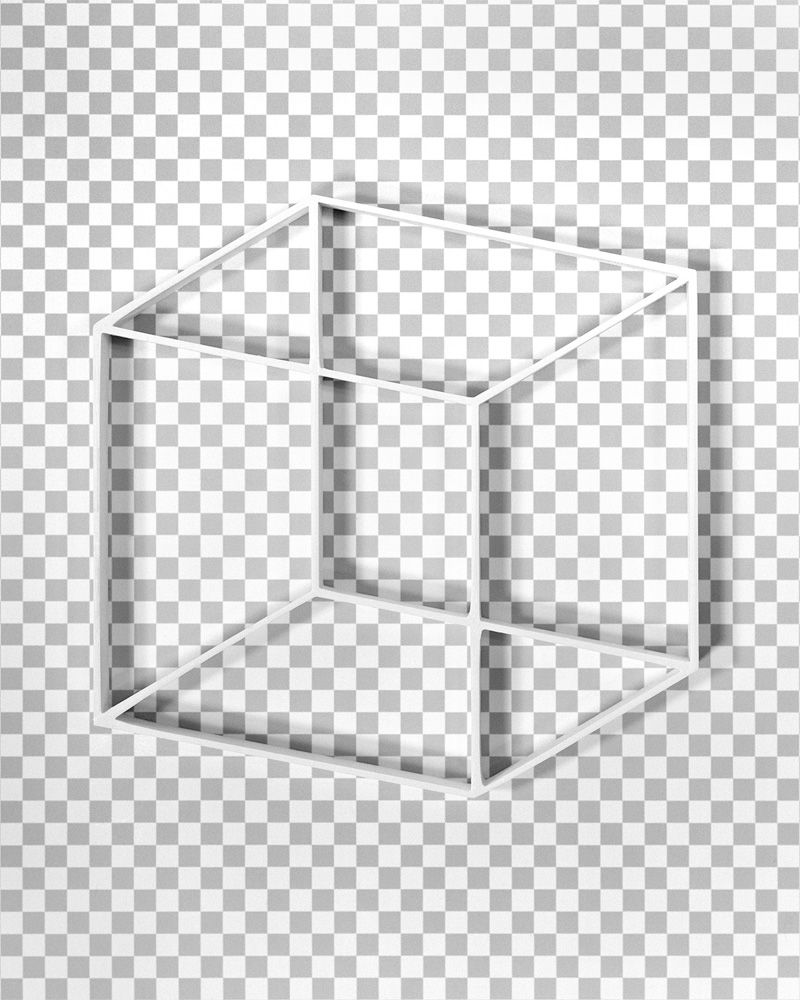

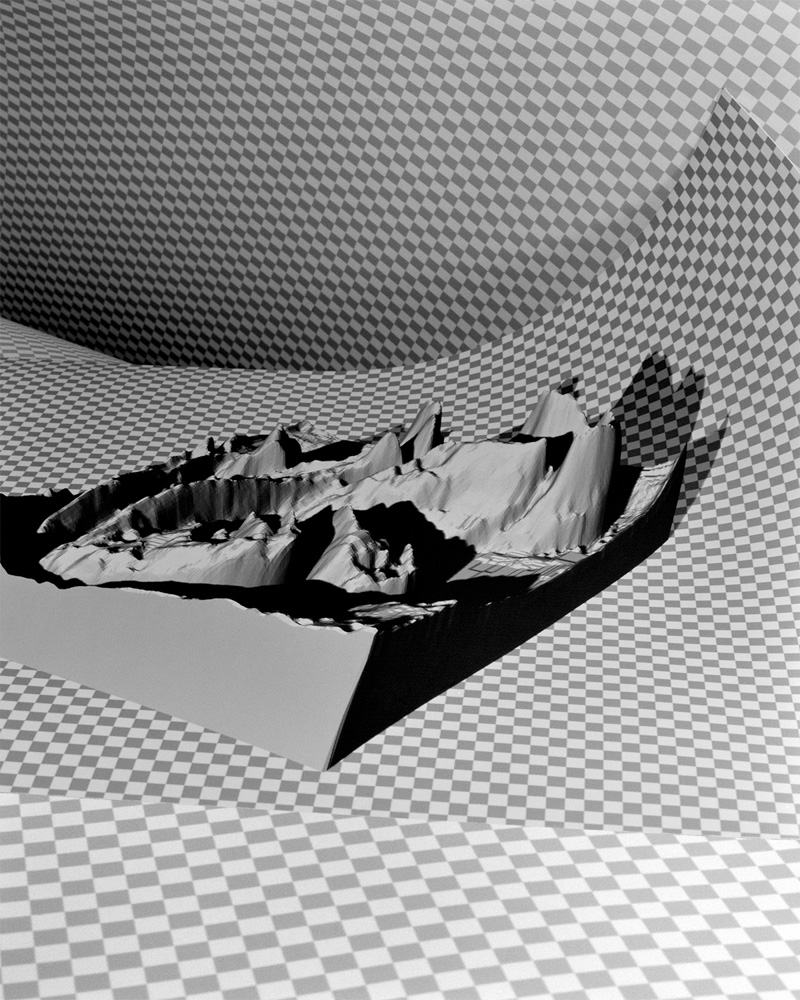

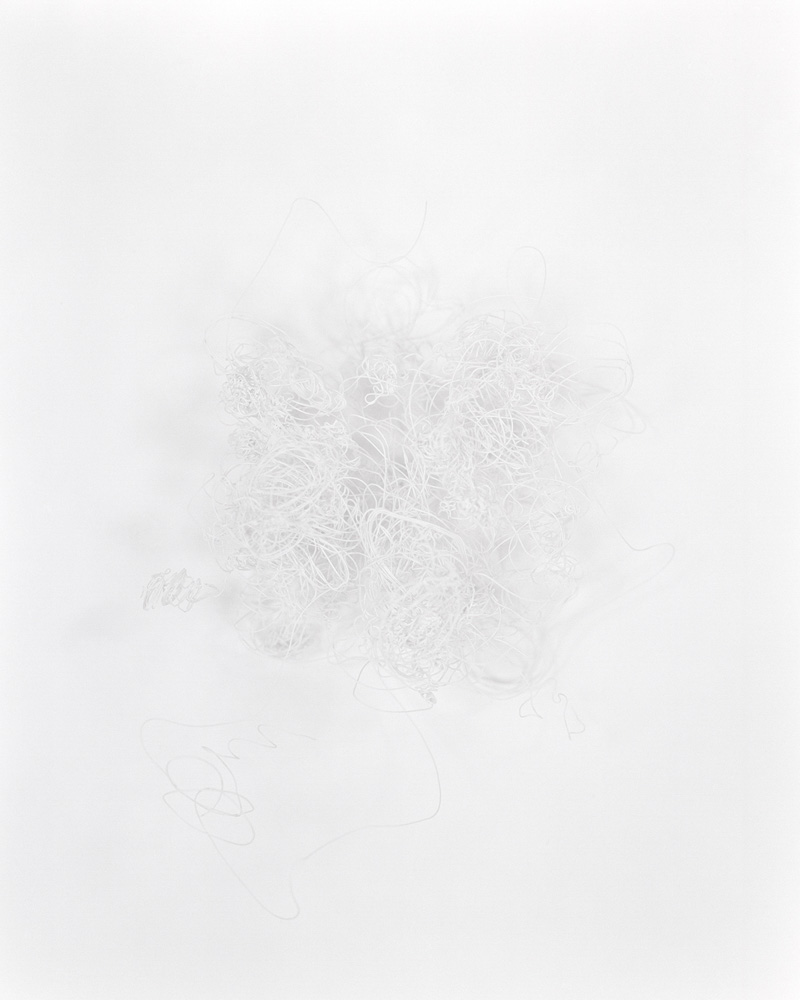

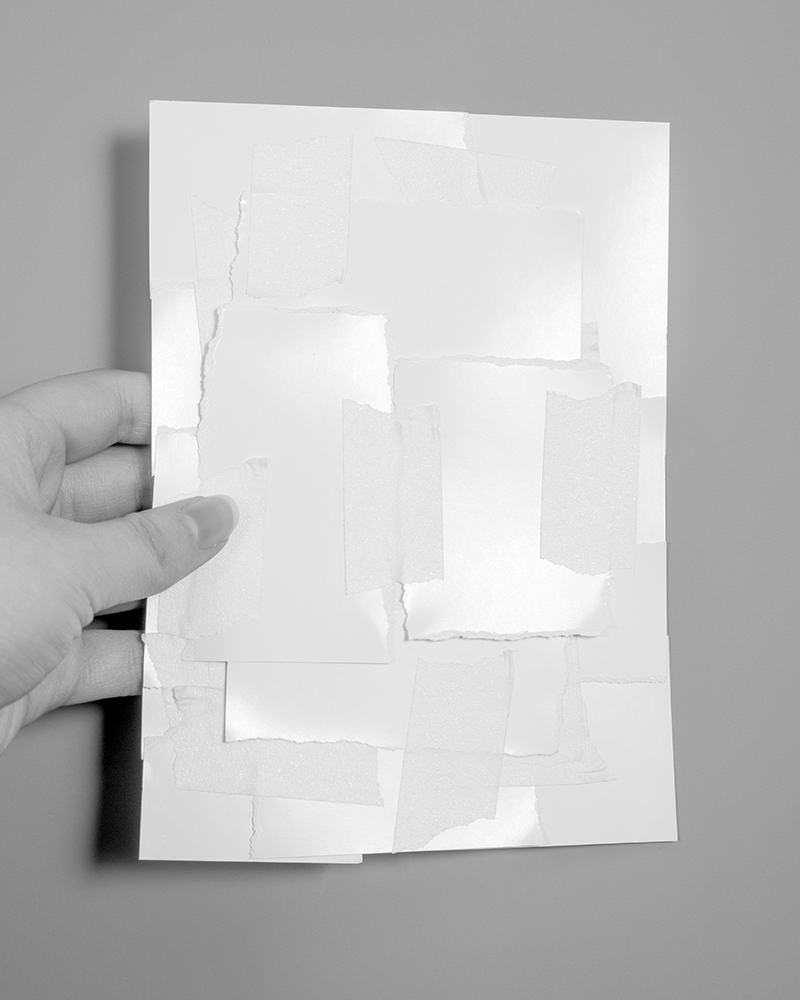

Photography’s vernacular reception has struggled with expectations of realism, enforced by advancing imaging technologies. Primarily, we are interested in this tension of the camera simultaneously creating an illusion of depth and flattening a space. To further investigate these ideas of photographic flatness, we consider the z-axis through 3D printing, and directly adhering images to the wall in our installations. To contextualize this conversation with the history of modernist photography, we use a traditional large format camera with black and white film as a filter to examine the traditional rules of classical photography. We challenge the notion of photography’s expected subject matter to distill the experience of looking at images to its fundamental properties: perspective, size, composition, and setting. We employ the photoshop transparency grid to reject subject matter, and question the role of a photograph in contemporary visual culture. As collaborators, we question authorship and representation. By referencing the digital production space, we are utilizing modes of production and reproduction to celebrate and question the possibilities of the medium of photography. – PWMD

How did you began working together? You both attended Lesley University College of Art and Design. How did the culture there and in Cambridge influence your practice?

P: From the beginning, working together was organic and intuitive. We met in the photography lab, where Marissa was working at the time.

M: Paal had just transferred to the program at Lesley University and I was showing him the lay of the land, including some of the most essential knowledge, like the must-take classes to enroll in and favorite professors.

P: We had pretty intense, theoretical conversations about photography from the beginning, and making work just kind of stemmed directly out of that. At the time, we were both fascinated with the complexities of how images existed in the world, and the problems with representation. We began materializing this by accumulating archives of images, saving from google, pulling from web pages, and etc.

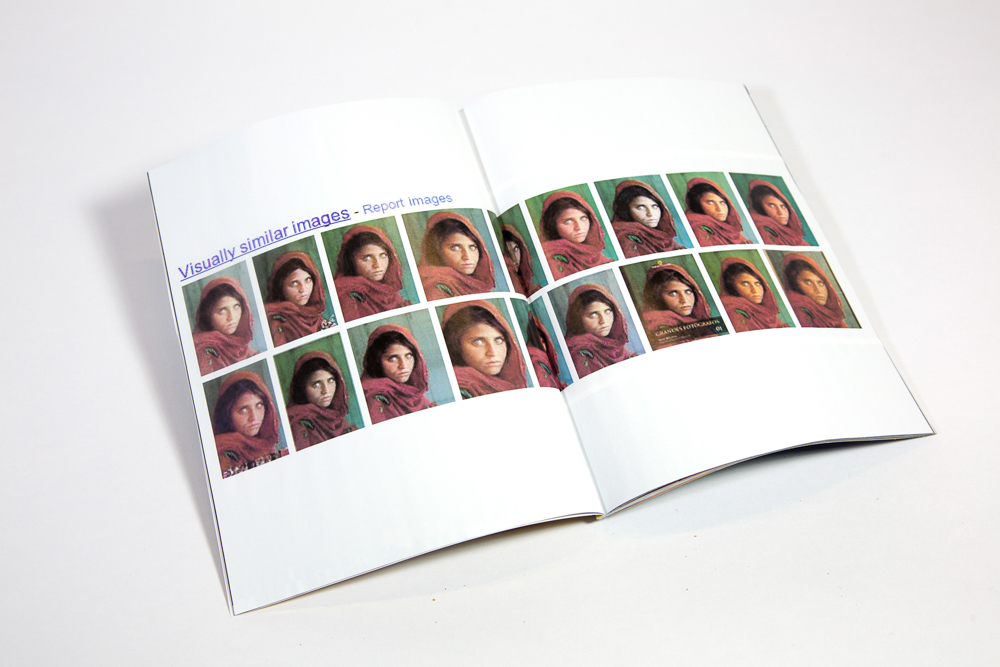

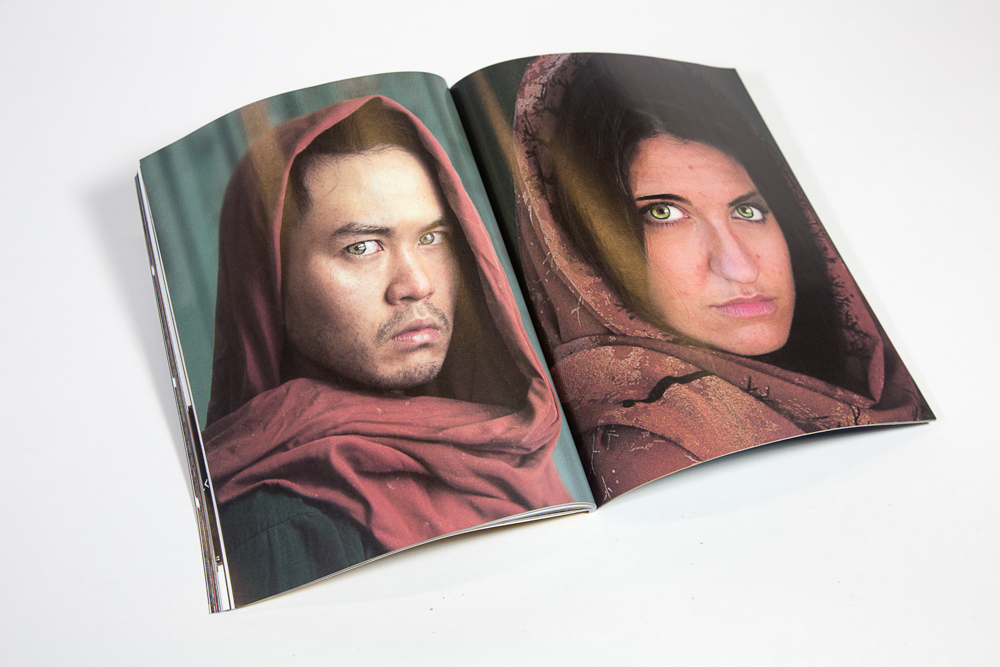

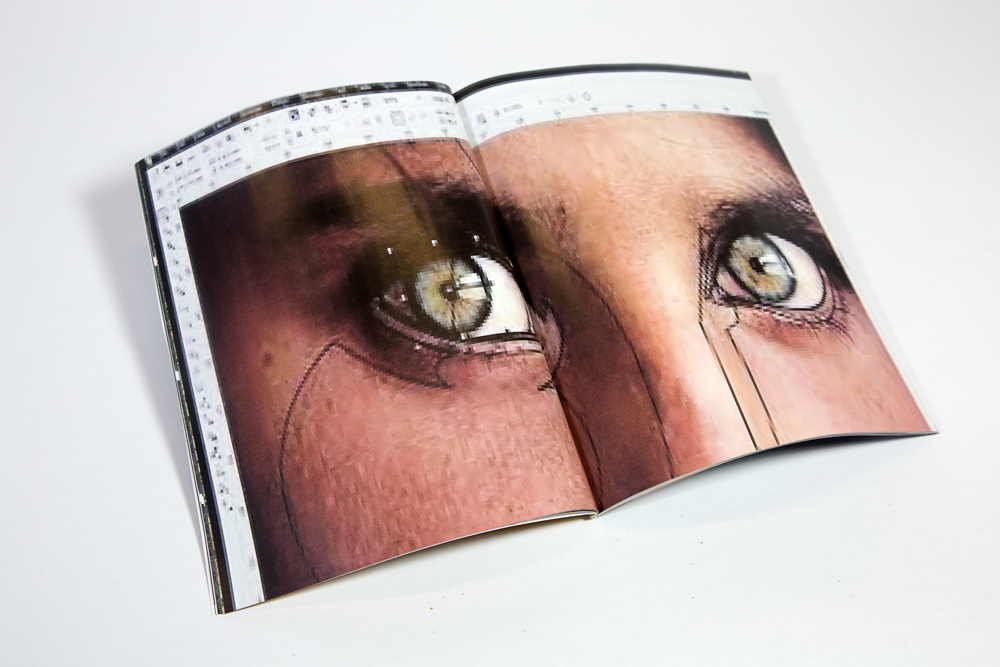

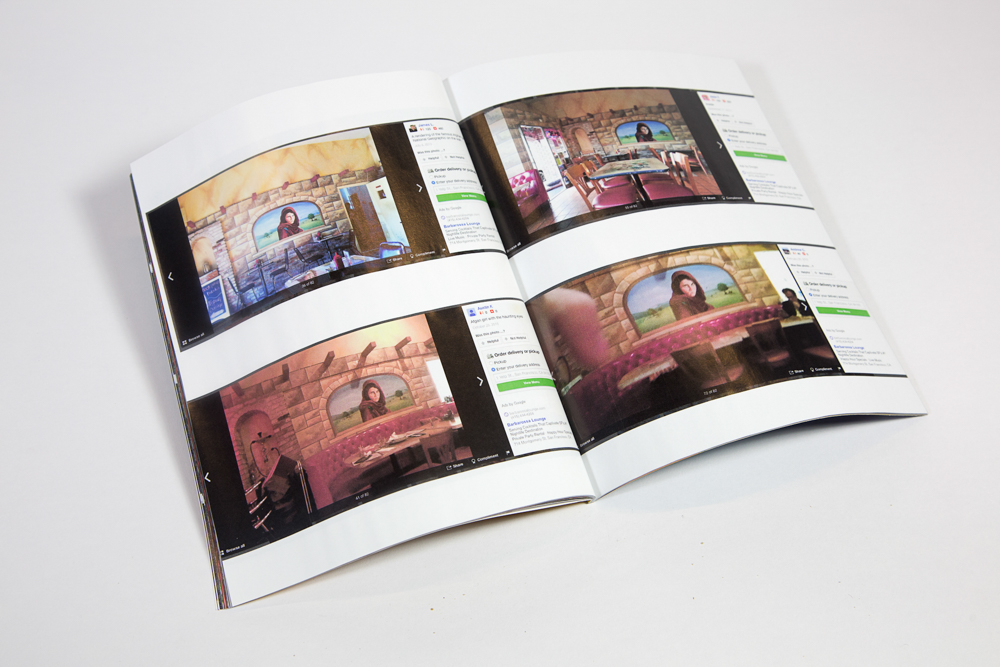

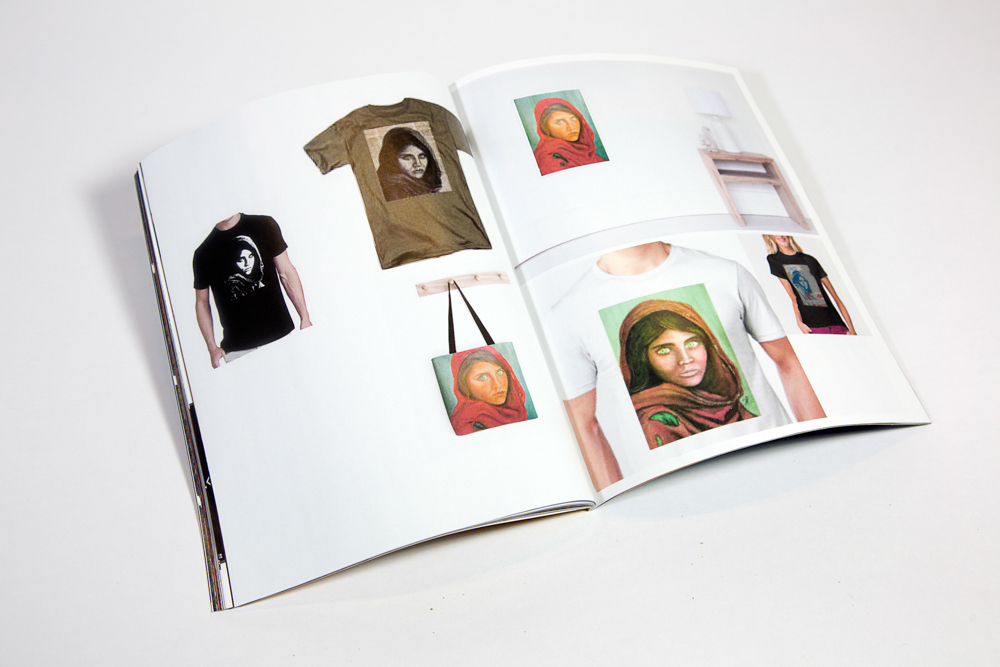

M: We grappled with these complexities and problems while still holding a deep love and appreciation for the medium of photography. This began our first project Afghan Girl, where we continually culled images from the google search “Afghan Girl” for several months, noticing the complications of the image that Steve McCurry created in 1984, how it resulted in an unpredictable trajectory of it’s intended creation. We are interested in this idea of how, as an image maker you lose control of the images you create. Our visual culture can re-contextualize and at times, capable of repurposing an image to the extent of complete loss of context. Specifically with the image Afghan Girl, we explore this by depicting how western culture has used Sharbat as a photoshop makeup tutorial, and people depicting her in a green forest landscape on a wall of an American restaurant.

P: Our work circulates around exploring these issues and problems of representation in the medium, while also highlighting the art historical tensions that are so important to recognize in these works.

Rather than point out the issues and problematize every aspect of representation, we are more interested in the tension between our love for photography and the complications with representation. This is what our work circulates around.

P: When we were attending Lesley University, we were in Harvard’s backyard. Not only we had our university, but also Harvard, MIT, and other greater Boston universities and museums resources. It was such a formative experience to be able to have access to a variety of exhibitions and materials on display at all of these institutions.

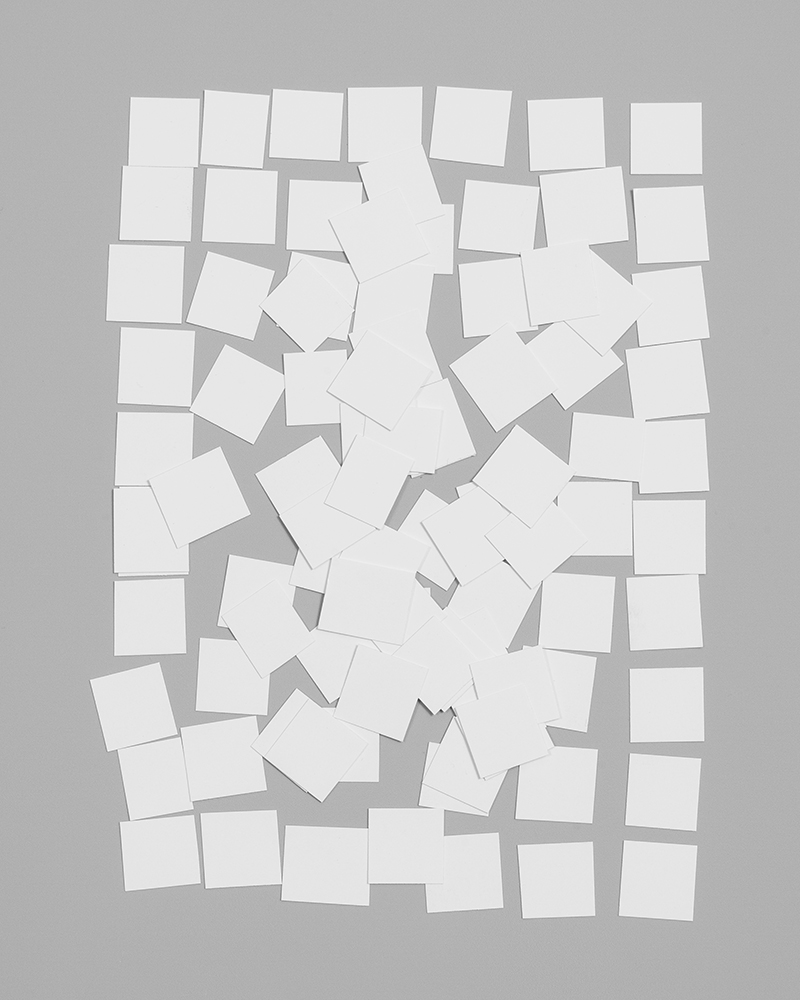

M: After making Afghan Girl together, it only felt right to complete our BFA thesis as a collaborative duo. With the support of the chair of our program at Lesley, we were able to obtain permission from our university’s higher administration to pursue our thesis collaboratively. Our body of work, A Flat World of Paper was our graduating thesis. We were highly focused on thinking about the multiple, especially in context to photographic technology and web presence of images.

P: I think the open source and highly communicative/connected nature of the internet era is something we’re both interested in, and has influenced our views of images and the way that we approach making art, what kind of value it holds, and the systems in place to protect the value of art.

What do each of you bring to the projects? What do you gain and what do you lose by collaborating?

M: This really depends on the project. We don’t necessarily have a working structure or assigned roles. They change per project and even each day in the studio.

P: We kind of float in and out of image making, editing/printing/production, and submitting to shows, and handling the email blitz. Our collaboration is nonlinear, but pushes each others ideas, and allows for the melding of ideas that form from what we call our “brain dump” sessions. This is our designated time to spew stream of thought, allow ourselves and each other to conversationally run in circles about things we have been recently thinking and reading. The result from these brainstorm sessions is that we take each others findings and run with the ideas. I like to think of this as a type of relay race, where we pass our thoughts and run with it, the only difference is at the end, the single thought we began with is now a fully considered art piece, book, website, gallery, non-profit, invention, etc.

M: We always push each others ideas, incorporate each others feedback into our own ideas, and provide motivation and positive reinforcement. We don’t really view collaboration as a gain or loss scenario, but rather an organic kind of extension of making artwork and being integrated in a community. Art is a highly collaborative process by nature, even though on the surface its formatted for the success of singular artists. I think we’re just trying to acknowledge that.

P: The art world has been created and continues to be formatted for a singular artist, and this is something that has not necessarily been a barrier, but has presented some complications as a result. For example, when we attend photo festivals as a collaborative team, we often only receive one name tag. Many submission forms don’t allow for more than one first and last name. It’s these instances where the art world system shows its gaps for a collaboration to logistically participate.

M: We have also faced many assumptions about working as a collaborative unit utilizing photography, due to the medium having one singular release cable, one shutter button. I believe we have received much of this criticism in the more traditional photo arena, where the community is fairly distanced from contemporary art conversations regarding image authorship and appropriation.

Can you speak to other influences and inspiration for your work in addition to the history of photography, and contemporary modes of photographic production (humor, play, deception, politics, illusionism)?

P: We, of course, admire other artists who are collaborators. Eva and Franco Mattes, Broomberg/Chanarin, DIS, etc. Some of the writers/critics we look up to are Lyle Rexer, Charlotte Cotton, and Hito Steyerl.

M: The folks involved in Black Mountain College (we really admire the environment created during that time) such as Ruth Asawa, Anni and Josef Albers, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, and many others who created this type of petri dish for an art student to thrive in. The ethos of BMC is highly present in our artist practice, along with our everyday lives regarding being a good citizen to the universe.

P: We have a rather wide scope for what we consider to be visual inspiration. I think as artists it is easy to get locked into a type of image that is “inspiration”, or a specific genre/visual style of art. We are also very inspired by vernacular photography, specifically on social media or on commerce platforms (craigslist, etc..) There’s a lot of hidden gems on social media – and it’s exciting how accessible the vernacular is with the internet!

M: Working with Photoshop transparency, we are interested in artists who challenge and play with the idea of depicting “nothing” or breaking rules of the traditional art model. Considered to be incapable to be visually depicted, Mel Bochner created illustrations of philosophical ideas. Sol Lewitt challenging materials and authorship. Hito Steyerl wiping green paint on her face, literally disappearing into the digital abyss of her backdrop in her piece, How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File.

You speak about working with the z dimension. Please elaborate on that in terms of your work and in terms of collaboration.

M: After making Afghan Girl and being in the thick of dense photography theory, our feelings toward the medium of photography were complicated, to say the least. We both have a deeply vested interest and love for photography. We, of course, highly admire Edward Weston’s silver gelatin photographs, Steve McCurry’s ability of creating popular portraits, but were recognizing how complicated photographic representation was. In this point of time, our education had revealed the “wizard behind the curtain” so to speak.

P: The Day Books of Edward Weston, Weston wrote extensively about objectifying women through photography. Sharbat Gula (the young girl depicted in Afghan Girl) did not receive a cent from the hundreds of thousands of dollars of profit earned from her image. Due to all of these issues, we started noticing that we were less and less infatuated with the medium. It felt impossible.

M: While researching, Paal came across how 3D scans are reliant on light and stitching together sometimes hundreds of images to make a 3d model. This notion of 3D scans effectively being images with a z axis fascinated us, and we were compelled to begin diving with this in our practice.

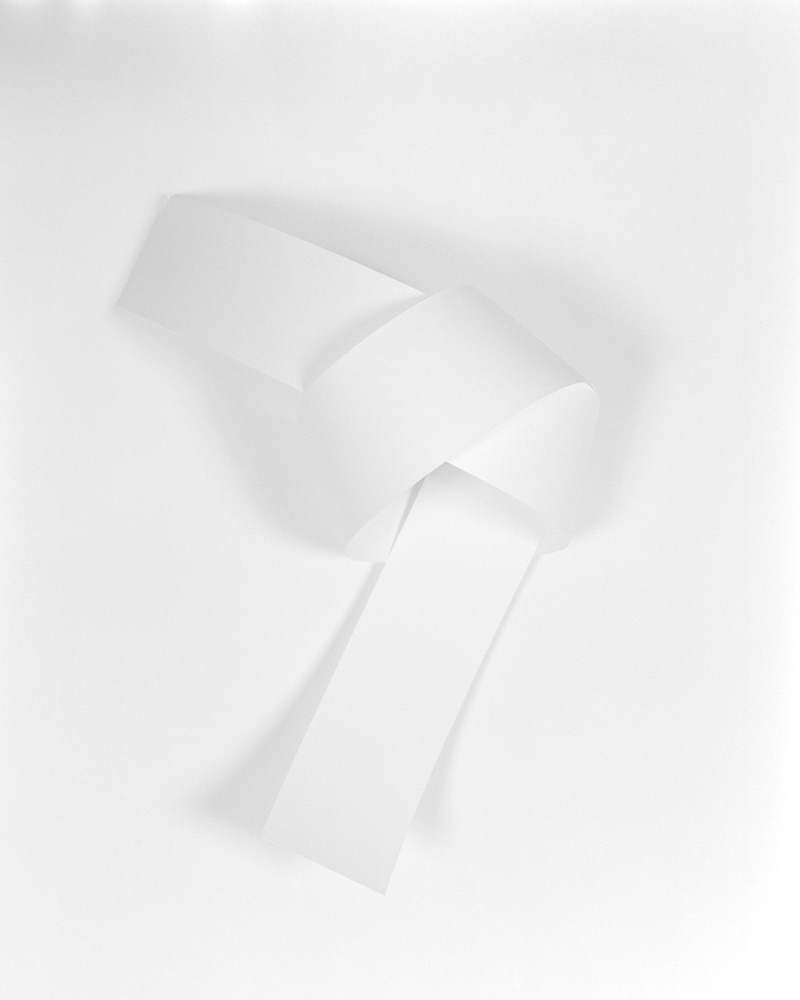

P: Photography is inherently a process of flattening. A flattening of affect, a literal compression of space, or a simplification of personality or character to a visual representation of that person. We were interested in this idea of a photograph both as a product of this flattening and also as an illusion of reality, or depth. 3D printing seemed to align with alot of these properties, and eventually we started incorporating 3D printed optical illusions in our work.

M: Incorporating this with our current ways of working (a very traditional, large format, black and white process) references the traditions of photography, while complicating their mechanics of truth and inherent believability with the introduction of digital processes. The rules that modernist photographers wrote were precise in defining photography as a truthful medium, and we sought to challenge their rules and parameters in our work.

With Paal currently in residence at Lillstreet in Chicago and Marissa in St. Louis, how are you maintaining a long distance collaboration?

P: Google docs, FaceTime.

M: Phone calls, iMessage image threads

P: We’re both becoming best friends with I-55 at this point. Maybe to loop back around to something we mentioned earlier, our collaborative process is not really a linear one. We don’t necessarily only constrain ourselves to only making work in the studio.

M: I have been commuting to Chicago on a bi-weekly basis, recently been in Chicago for the past seven weekends straight, don’t visit our Saint Louis apartment, it’s a mess! For our most recent exhibition, image>image size at Lillstreet, the majority of the work in the show as created with us both together in the studio. This isn’t always the case though – just what the show required! We’ve been talking about a few ideas for de-materialized pieces, and we’re always experimenting, so that’s bound to change!

P: The commuting goes both ways. Part of that, unfortunately, means that I’ve been on more overnight greyhound bus rides this year than I care to admit, haha. Also managing production, shipping, etc. of current projects, exhibitions, and new work. We both do it all.

M: Our closest friends have been huge contributors to our long-distance artist practice. Paal and I recently curated an exhibition at Granite City Arts and Design District, tilted Pixel. We couldn’t have pulled it off without the help of our Saint Louis, and newly found Chicago friends.

A Flat World of Paper

Since its creation, photography has relied on available technology. Despite evolving methods of image production, a constant function of photography is that it simultaneously flattens a space and creates an illusion of depth. We are interested in this tension, and how it promotes perceptions of realism in photography.To further investigate this idea of photographic flatness, we consider the z-axis that has been neglected from the photographic conversation. Through 3D printsand photographic still lifes, we reinterpret the materials and expected subject matter of photography to distill the experience of looking at images to its fundamental properties: perspective, size, composition, and setting. We use traditional tools of photography; a 4×5 camera and black and white film, as a filter through which to examine these historical tensions.

In our image based world, three dimensional things become flat, and flat things become three dimensional.To accompany this conversation, we implement methods of installation that reference and challenge traditional modes of displaying photographs. We adhere images directly to the wall to emphasize flatness of paper, and react to the viewing space.

As collaborators, we question authorship and representation in art. We employ the photoshop transparency grid to reject subject matter, and question the role ofa photograph in contemporary visual culture. By referencing the digital production space, we are utilizing modes of production and reproduction to celebrate and question the possibilities of the medium of photography. –PWMB

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025