Art + Science: Blood and Kin: Michael Koerner

Michael Koerner, Ph.D. (b. 1963) is a scientist and a photographer who specializes in historic/alternative photographic processes. As a scientist and organic chemistry professor, he conducts scientific research. In his series My DNA, he experimented for years with chemical reactions to create organic abstractions using tintype process. Yet, beyond aesthetics, his work reflects the story of his own family’s history. Specifically, his work is directed toward the genetic mutations within his family which have been a direct result of both parents having high exposure at separate times to gamma radiation from nuclear explosions. As a young girl, his mother lived less than 40 miles from where the nuclear bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. His father, during his service in the U.S. Navy, was exposed to radiation from a nuclear fusion test. Koerner’s visual representation of aesthetic blossoms and fern-like patterns depict an invisible enemy, whose silence and pain spans generations.

My DNA

My mother was eleven years old on August 9, 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. She lived in Sasebo, Japan, less than 40 miles away from the blast. About half of the 80 thousand deaths from the attack on Nagasaki occurred in the first day, while the other half of the deaths occurred from radiation sickness and burns over the following months. Realistically, the ultimate death toll is much higher when you approximate the long-term effects of severe, acute exposure to gamma radiation

My father was also subjected to radiation exposure, but from a nuclear fusion test in 1954, after his service in the Korean War, during the US Navy’s Operation Castle Bravo. In this nuclear testing, my father was stationed aboard one of many observation ships, which were all positioned too close to the multi-Megaton detonation that nearly capsized the U.S. naval vessels. I have read letters from my father asking the Navy to share data to help explain why his shipmates were being diagnosed with rare/obscure and multiple cancers at a much higher rate than the general population. To my knowledge, he never received any information and definitely no admission of government culpability.

I am the oldest of five brothers. Unfortunately, the next born son of my parents lived for only several days. The next son was still-born and the next was miscarried late in the third trimester. My youngest brother, Richard, eventually succumbed to complications associated with two separate bouts with cancer of the lymphatic system. He lived until he was 32 years of age. The cause of each of these tragedies can be traced to genetic abnormalities. My brothers’ fates (and potentially my own one day) can be linked to my parents’ individual exposure to gamma radiation from those separate, historic atomic detonations. There is a tremendous amount of pain and guilt associated with these horrendous endings. It is almost impossible to eliminate or even subdue the feelings that something somehow could have been done differently or avoided.

The long-term effects of severe, acute exposure to gamma radiation led directly to many future health complications for both of my parents and implicitly to genetic issues for my siblings and myself. This family medical and genetic history and my experiences with “survivor’s guilt” drive my “artist’s hand.” I like to call my art purposefully abstract. I make distinct chemical choices (developer type, placement, amount, temperature, concentration, etc.) and over-all design decisions in the darkroom, but for each art piece (just like it is in genetics), the final outcome is ultimately out of our control.

Koerner is currently a Senior Lecturer of Organic Chemistry at the University of Illinois-Urbana/Champaign. He combines his training in the chemical sciences with his photographic darkroom expertise to create unique chemigrams on wet plate collodion surfaces.

Koerner has been working on alternative/historic photographic processes in the darkroom for almost twenty years. His early work started with cyanotypes, and kalitypes, then moved to salt, albumen, and platinum/palladium prints of large format and digital negatives. Eventually, Koerner moved his focus to the direct-positive, wet plate collodion processes (ambrotypes and tintypes) and concentrated on formulating specialized developers to make chemigrams and photograms on sensitized collodion surfaces.

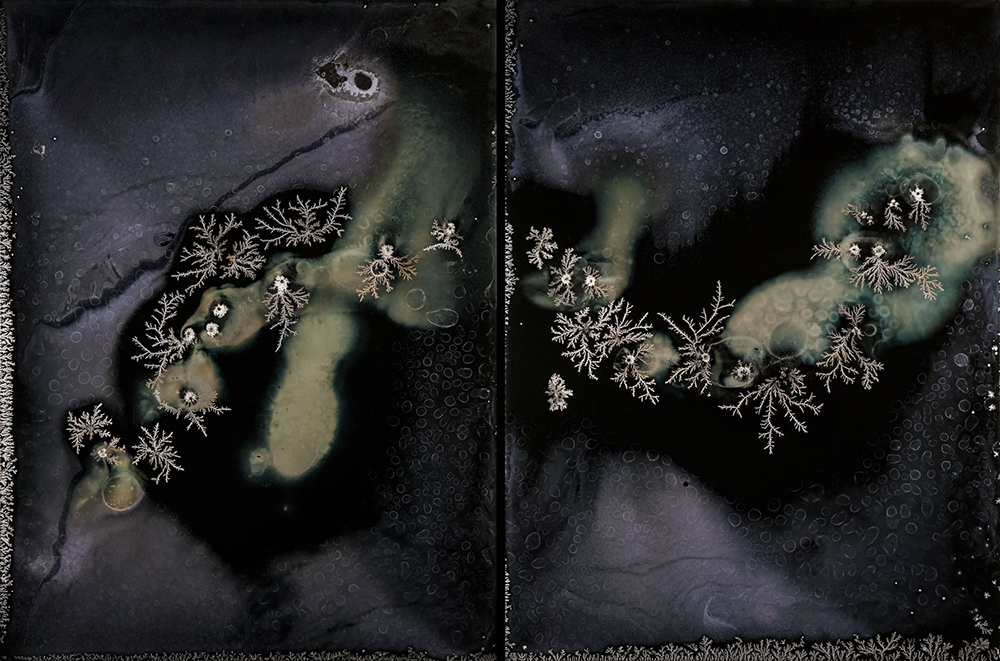

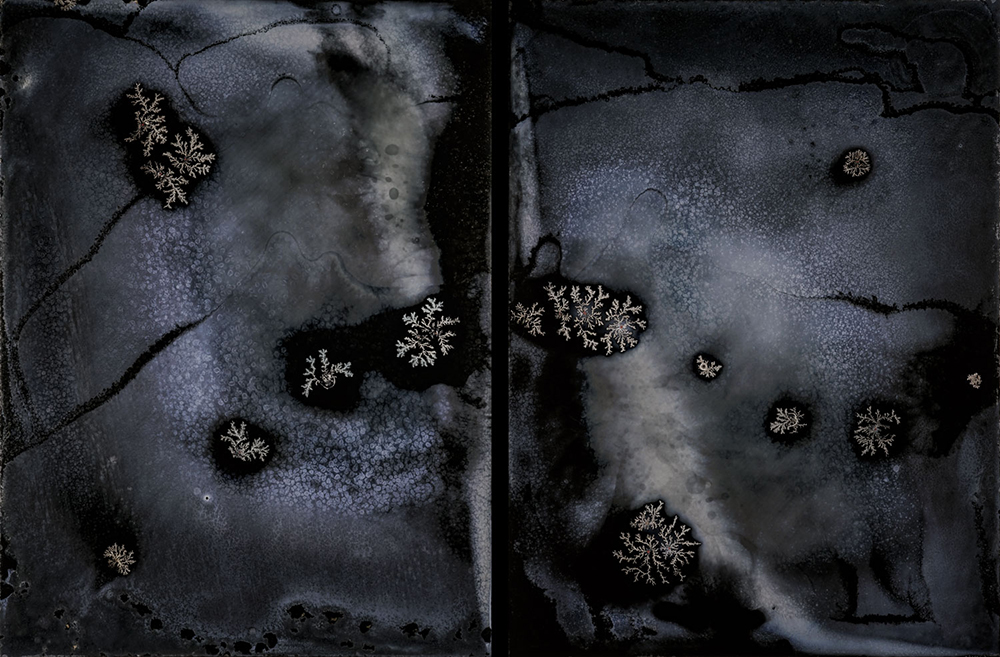

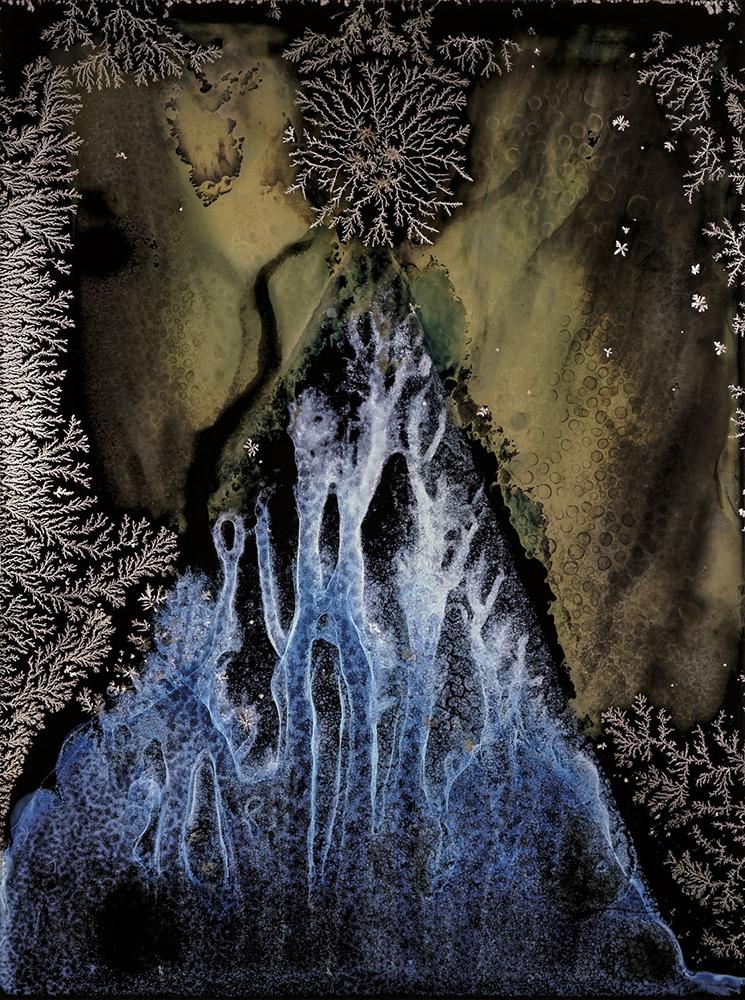

Each art piece looks like a topographical view of a distant landscape; captured celestial episode, biological or medical mishap, or schematic of a mechanical, alien contraption. When observing these tintypes in their entirety, one sees that the imagery is purposeful, intentional, deliberate, and organized, which is difficult to portray and a counter-intuitive process in creating nonrepresentational work.

Upon close inspection, Koerner’s chemigrams always include small, detailed fractal patterns associated with an event that is almost mathematical, but born of nature. Koerner uses his knowledge of chemistry and information gleaned from the photographic literature from the 1800s to produce these fractal growths of silver that are intended to simulate the bursts and radiation from nuclear reactions as an exploration of his family health history and genetics. His work is represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery.

Addendum

Many studies on the effects of radiation from the two atomic bomb blasts in Japan have been performed. In fact, almost all of our understanding of the effects of nuclear fallout comes from examinations of these two events. However, I don’t know of any studies that have specifically examined the effects on the genetics of the children of survivors, who were aged 10-14 at the time of detonation. Specifically, I would love to see a comprehensive examination of genetic data (and not studies based on surveys/questionnaires, which are mostly skewed, selective, voluntary and inaccurate) from children whose mothers (not fathers) were of the age correlated to reproductive development (egg maturation). Crudely, if we assume that women are born with about one million eggs, and about 400,000 are still available during their first menstrual cycle at the age of 11 or 12 (my mother’s age in 1945), then only 360+ eggs will develop into maturity across their entire reproductive lifespan.

Therefore, a woman’s egg cells, which are gametes, are part of the germline. Any genetic mutations to the DNA of an egg cell will be passed on to the progeny – the cells of the offspring will have no way of knowing mutations in their genome exist and all the offspring’s cells will proliferate with this mutation. The offspring’s biochemical mechanisms will not initiate normal DNA repair processes, because their initial (mutated), inherited genome is considered the “normal” baseline.

In contrast, all other maternal cells are somatic, so point mutations from gamma radiation in those (non-germline) cells can be repaired with no (or very little) effect on offspring. Hence, multiple conflicting reports on the effect of nuclear fallout on the survivors (and their offspring) have been published, because they have a mix of survivors/subjects with varying degrees of participation and sample sizes.

Therefore, in my specific familial case, my mother was walking, breathing, and living in an environment undergoing an active decades-long radioactive decay process; eating plants grown and animals raised on the contaminated soil and in the irradiated waters; drinking water that has leached mineral isotopes; etc. for many years, while her reproductive health was developing. Likewise, the somatic cells’ DNA mutations in my father’s genome very likely contributed to his own rapidly degraded health, and might have (less likely, unless stem cell mutations occurred in the testes) contributed to my genetic fate.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

European Week: Kacper KowalskiMarch 4th, 2024

-

Debbie Fleming Caffery: In Light of EverythingFebruary 11th, 2024