Mehves Lelic: On Adornment

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series On Adornment, by Mehves Lelic.

On Adornment

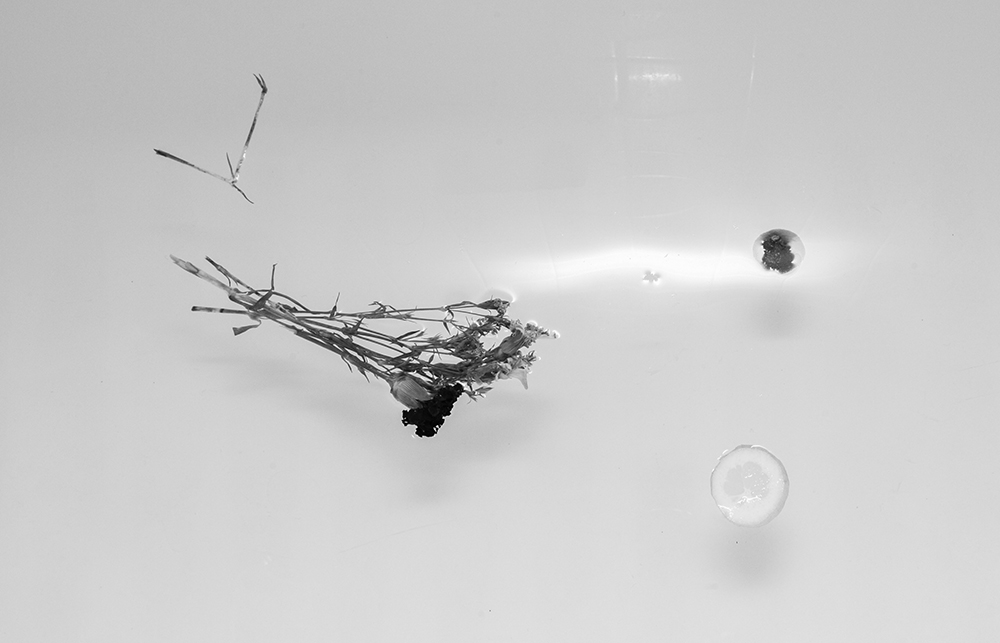

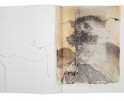

This series explores the relationship between adornment and selfhood and its inherent visual symbolism(s). I am intrigued by the physical signifiers that are often interpreted as the longing for and the rejection of a gaze, and the mitigation of the two opposing sentiments. Focusing on my immediate community of Muslim-American women and the symbols in our lives, I picture the complexities of self-image, selfhood, and material and spiritual belonging. It seems more often than not that the current political climate in the US made us hyper-aware of our heritage as a community. The images aim to evoke the subtle, elusive and quite intensity of clinging to this said heritage, but remaining caught in a globalized, ever-connected world where pride and fear seem to co-exist.

Daniel George: In your artist statement, you write that the current political climate in the United States made your community hyper-aware of its heritage. How long had this concept been building in your mind? Was there something specific that you were seeing and experiencing that finally pushed you to make work addressing this issue?

Mehves Lelic: Settling in the US permanently has created a visually hyphenated world for me, especially in material culture – not just in terms of the sentimental value of objects but in terms of how the modern world and global consumerism imbues these objects with political, socioeconomic and cultural meaning once they are transplanted. Things live different lives home and abroad, so to speak, and I’ve been interested in that for a long time.

The anti-immigrant, and especially the anti-Muslim rhetoric in the past few years has definitely led to a sort of reckoning of this visual world. I grew up in a culturally Muslim and cosmopolitan family in Istanbul and spent several years in Chicago. Until I moved to a small town on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, not many people would inquire what type of immigrant I was. Even when I was asked, my first instinct was to point out a country of origin rather than religion. Not all Turkish people are Muslim, and not all Muslims are Turkish. There is a very nuanced piece by Shadi Hamid on Medium, “How Donald Trump Made Us Muslims,” where he addresses how between 9/11 and the Muslim ban, and many other instances of xenophonia in between, Muslims of various ethnic backgrounds became a “we” in America. This made its way into my work in several ways – one factor was developing a deepening interest in common themes across beauty, self-image, adornment and the performance of femininity in such a massive and diverse community that up until then to me personally had felt only vaguely representational of its members. Another was the actual event of settling in the US and beginning to call it home, and starting to accumulate things such as a printer, a beach umbrella and small appliances that cannot be used effectively with a plug converter.

DG: You mention your interest in exploring opposing sentiments regarding the gaze. How would you say your photographs accomplish this?

ML: I think the medium’s immediate association with spectatorship is where the exploration originates. Photography is multitudinous; the very impulse to create one must acknowledge the act of spectatorship itself, especially in our image-dominated world. In the work, I try to offer a gaze that the subject returns, either back to the camera, and the viewer, or to another figuratively or literally reflective surface or object. Perhaps relevantly, I am interested in exploring the longing to be desired on one’s own terms, so able to return the gaze, and so undeniably able to embody the shapes and forms of a more complicated type of beauty – that for instance simultaneously has the soft curve of the pear and the plastically angular artificiality of the aluminum foil in Study 1. I do think my cultural background comes into play here as well; the ideal woman I was presented with had to be naturally desirable but also to vehemently resist being desired for any of her qualities. It’s impossible not to see through that as you become an adult.

DG: Your perspective as a Muslim-American woman gives a unique and important significance to the people, places, and things that are your subjects. I certainly bring my own interpretation to your photographs, but what insights would you provide myself and other viewers to better navigate them?

ML: Ha, I had to think about this one. I think the specific brand of secular Islam that I grew up with is very present in the work. It emerged in the early years of the Turkish Republic as a fitting solution for its Westernization effort and its interpretation has been shaped by political, economic and social developments. That creates a curiosity and crisis of looking, especially in this project – I myself can’t fully and clearly navigate some of these religious and cultural elements due to the sheer variety in how different people live with that identity, and perhaps that is why I am making these photographs.

DG: Your photograph of the figure lying in bed, facing the window and looking at a cell phone, seems to directly address the idea of heritage and global-connectedness that you are interested in exploring. What is your experience with this intersection of worlds?

ML: It has a few dimensions and I will try and describe the most pertinent ones. Heritage is often thought of as linear, even I am guilty of this. However, the ability to tap into a wealth of visual and textual information has completely transformed that linearity. Ties to the various parts and periods of life can now so easily be conjured. This gives the actual geographical divide between me and my past a sense of artificiality. That figure in the image can broadcast any moment of her life to a family member so easily, and that may be she is doing precisely, the phone screen is intentionally left unsharpened and unfilled. The broadcast would have a simultaneous feeling of proximity and rift that is overwhelming. Anyone who has longed for the physical manifestation of a place or a person who is inaccessible in that moment has felt a version of this I am sure.

The second dimension is the act of conveying memory and experience in the form of images. This also creates simultaneous proximity and distance, which leads to the obsession with exchanging images. The images make the rift look not so huge, but they are required precisely because the rift is truly massive and frankly, heartbreaking. There are so many delightful oddities in my life here and they are hard to convey in this spontaneous, everyday visual language, perhaps because there is already an over-saturation of that kind of image that falls short of say, depicting a very complicated friendship, or the mall food court. The intersection of the two worlds you describe requires these two types of images to live together on my phone and in my WhatsApp chats: those that have a lot of nuance that I feel an impulse to make for my work, and those that I make to communicate to my family that have to operate in a relatively indexical manner, mostly picturing my young daughter embracing other people’s pets.

DG: Looking forward, what are you hoping to do with this work?

ML: I feel in many ways that it is still developing! I would like to introduce less subtle references to the heritage of Orientalist painting and how that specific form of picturing women left a legacy. That seems like a natural “next challenge”. The contemporary photographic depictions of women of Middle Eastern heritage often adopt an Orientalist approach today; subjects, posed in exceedingly beautiful yet limiting settings, seem to possess allure but lack agency, adopting what Edward Said describes as a static and essentializing Western overture on heritage and culture -especially if they dwell on the limited axis of socioeconomic mobility and consumerist modernization. Out of a frustration with these images, the appeal of which rely on the visual otherness of their female subjects in particular, I have begun to think about what made Orientalist images and the inherent “otherness” in these portrayals tick, as well as how they could be countered using aesthetic and conceptual glorification in contemporary photography. The question, as always, is how to revert that!

Mehves Lelic (b. 1990, Istanbul) is a photographer and educator. She received her BA from the University of Chicago and is adjunct faculty in photography at Anne Arundel Community College. She is the recipient of a National Geographic Expeditions Council Grant, a City of Chicago Individual Artist Grant and a Turkish Cultural Foundation Cultural Exchange Fellowship. Her work has been exhibited at Filter Space (Chicago, IL), Academy Art Museum (Easton, MD), Ogden Museum of Southern Art (New Orleans, LA), Biggs Museum (Dover, DE), Cosmos Arles (Arles, France), Institute Des Cultures D’Islam (Paris, France), and the Photographers’ Gallery Istanbul and the Rotterdam Photo Festival, among others. Online and Print publications include the National Geographic, GEO Magazine, Ain’t Bad, Der Greif, Humble Arts Foundation, the In-Between Magazine, PhotoVogue and Mitos Magazine. She lives and works between Istanbul and the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025