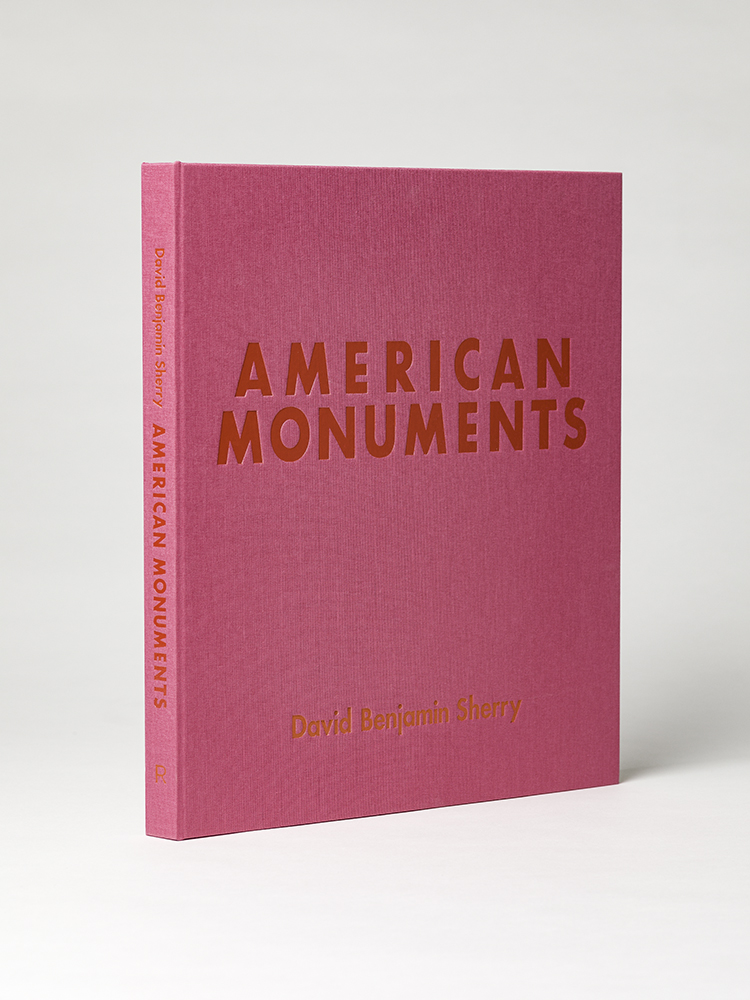

David Benjamin Sherry: American Monuments

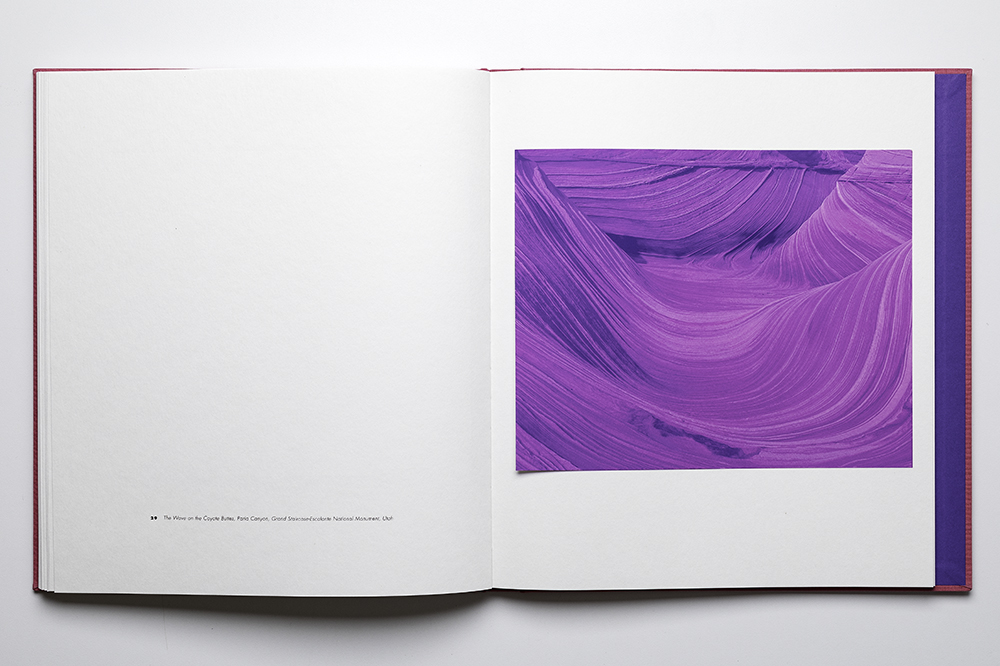

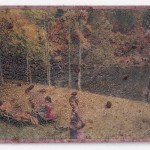

Using analogue photographic methods, David Benjamin Sherry reexamines the classic tradition of landscape of the American West. In his book American Monuments (Radius Books, 2019) he presents photographs with vivid monochromatic palettes to shed light on the exploitation that threatens our country’s national monuments. Using 8×10 large format film, Sherry captures details and pristine qualities of the land. By pushing boundaries of darkroom techniques, he creates saturated monochromatic colors enticing the viewer into a world of alarming beauty. This transformation of the landscape offers a myriad of interpretations ranging from an immediate threat due to human impact to hope amidst environmental adversity. Sherry presents the viewer with an opportunity to contemplate the deep connections we have with our planet – what is seen on the surface verses what is hidden below. The viewer is left to contemplate where the truth lies.

Like many others, I watched in horror as the Trump Administration set out to lift the protected status of designated national monuments in order to lease the land for coal and uranium mining and oil drilling. Starting in the spring of 2017, I set out to explore, commune with and photograph these lesser known, wild and hard-to-reach places. Spending months alone in these threatened sanctuaries, I became increasingly motivated to protect them, in part by engaging the tradition of photographic preservation. Photographers’ efforts to use their images to advocate for the protection of lands began in the 19th century with the US Geological Survey, and is inextricably bound up with the United States’ complicated mission of simultaneously wresting lands from Indigenous peoples and preserving that land for future generations of Americans.

With the body of work included in this book, I aim to revivify and radicalize American landscape photography—to both celebrate and challenge the traditions of the past, such as formal mastery of pre-digital, film-based, darkroom photography, and to continue a tradition of deep communion with far-flung forests and deserts. Since my practice is also centered in education, it requires a rejection of perpetuating a corrupt political history of the American West, with its glorified legend of freedom, fabricated from stolen lands which have been consistently abused and destroyed. My photographs both engage with and seek to subvert the images often associated with that history: large-scale, majestic, black-and-white photographs of pristine landscapes, often shot by straight, white men in the service of perpetuating a colonialist notion of Manifest Destiny.

Like many of my photographic forebears, I use an 8×10 large format film camera, which allows for an unrivaled level of detail. However, when printing, I’m not interested in depicting the way the subject appears in reality, but rather its potential for emotional resonance between viewer and subject. Color is a conduit for me to make those feelings visible. Like black-and-white photography, my monochrome, analog process foregrounds form, light, and composition, untethering the image from the constraints of straight representation. My aim is for the print to demonstrate my empathy toward the landscape and to help others better understand our physical and spiritual connection with the Earth. The color is emblematic of that intense connection, and yet simultaneously connotes my sense of otherness as a queer person. My travels have become a tool for processing the American queer experience as I navigate through rural spaces and communities stereotypically considered unsafe for queer people; queer narrativity is built into both the process and product of the work.

We are losing our grasp of our deep interdependence with the Earth; as that connection disintegrates, our survival as a species will likely go with it. While these photographs grapple with a grim political circumstance, I hope they also awaken an adventurous spirit and sense of reverence. They represent resistance, self-determination, and optimism in the face of adversity—core American values that are as imperiled as the land itself.

David Benjamin Sherry (b. 1981, Stony Brook, NY) currently lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. He received a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design in 2003, and his MFA from Yale University in 2007. Past group exhibitions include Ansel Adams In Our Time, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Greater New York 2010, at MoMA PS1, LIC, NY; The Anxiety of Photography, Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, CO; Lost Line, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; and, What Is A Photograph?, International Center for Photography, New York, NY. His work is in permanent collections at the The Nasher Museum of Art, Durham, NC; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Wexner Center of the Arts, Columbus, OH; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; the Saatchi Collection, London, UK; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. “Earth Changes”, a catalogue of Sherry’s landscape work, with an essay by LACMA curator Britt Salvesen, was published in 2015 by Mörel Books, London. Radius Books will publish Sherry’s monograph “American Monuments” this fall, with essays by environmentalists and activists Terry Tempest Williams and Bill McKibben. The series was also featured in a cover story by Aperture Magazine in Spring 2019. Sherry will be joining Yale’s MFA faculty this coming fall 2020 as visiting critic.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Mehrdad MirzaieJuly 24th, 2024

-

Charles Shuford: Blue is For BoysJuly 12th, 2024

-

Sarah Lazure: SarahJuly 11th, 2024

-

Kirsten Hoving: Fabricated VisionsJuly 10th, 2024

-

Gary Owens: In the RoomJuly 9th, 2024