Strange Light: The Photography of Clarence John Laughlin at the High Museum

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Bat, 1940, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1981.93. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

On the heels of Halloween, who better to feature than “the Father of American Surrealism,” Clarence John Laughlin? Born in 1905, Laughlin is best known for his haunting images of decaying antebellum architecture in his hometown of New Orleans. His work is the subject of an exhibition at the High Museum in Atlanta, Strange Light: The Photography of Clarence John Laughlin.

Strange Light is on view at the High Museum through November 10, 2019. Visit the High Museum’s website for more information or to purchase tickets. The exhibit captures Laughlin’s signature bodies of work made between 1935 and 1965 and includes more than 80 prints—some on display for the first time.

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Ghostly Arch (#2), 1948, printed 1949, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, bequest of the artist, 1985.109. © The Historic New Orleans Collection

About the Artist

Clarence John Laughlin was an American photographer best known for his surrealist photographs of the American South. He made his first photograph in December 1930, keeping meticulous records of every exposure thereafter. During the last half of the decade, he made more than two thousand negatives of his beloved New Orleans French Quarter. For his first professional job, Laughlin worked as a Civil Service photographer with the United States Engineer’s office, where he documented construction work. After a brief stint in New York working for the Vogue magazine studios, he became Assistant Photographer at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

In 1946 Laughlin returned to New Orleans. His architectural studies of antebellum plantation homes, published as Ghosts Along the Mississippi, brought him acclaim, and in the 1950s he focused on homes of the late 1800s, believing that architecture “…is the one art most completely involved with human lives.” He stopped photographing in 1967 because of crippling arthritis, and began to catalog his carefully documented 17,051-image collection.

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Improbable Dome (No. 1), 1965, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet; her family members Josef, Jiri and Alma Beran Mann, all of whom perished in the Holocaust; and Sir Nicholas Winton, the British hero who orchestrated Charlotte’s escape with 669 Czechoslovakian children in 1939. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

“From allegorical social commentary, to expertly constructed narratives, to bizarre material experimentation, Laughlin’s effort to access a higher artistic potential for photography is evident throughout his career,” said the High’s Associate Curator of Photography, Gregory Harris. “His desire to push the limits of photographic possibility paved the way for generations of artists and the growth of the medium into a tool of magical potential.”

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), Water Witch, 1939, printed 1940, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase, 1978.63. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Laughlin considered himself a writer first and a photographer second, and saw image making as a form of visual poetry. His writing style is intense, dramatic, and at times bizarre — much like some of his photographs. Below is an excerpt from an article he wrote for Harper’s Bazaar in 1941.

Surrealism in New Orleans by Clarence John Laughlin

Before surrealism had a name, it existed in New Orleans.

For many years New Orleans was a beautiful and luxuriant deathtrap. Virtually encircled by a ring of swamps, subject to the feverish tempo given vegetable and insect life by the semi-tropic heat and rain – the specters of death and pestilence materialized in horrible, intricate, and multiple fashions…

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Enigma, 1941, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase, 75.76. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Inextricably fused with these ominous physical factors was a system of religious beliefs whose fervor and whose fantastic form, as evidenced in the elaborate and unparalleled development of funeral art in New Orleans, had its source in the psychological sub-strain of fear…

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Unending Stream, 1941, printed 1973, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase, 75.77. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Here, then, in these photographs, is a New Orleans of which tourists, and most New Orleanians, moreover, are unaware. A New Orleans where the cultures of France and Spain, fed on an environment unparalleled in its violence of decay, took root to produce an efflorescence unlike anything ever seen in Europe; and in which the human spirit reached a singular flowering. A New Orleans that is vanishing utterly.

You will find it in some the early cemeteries—the Cypress Grove, the Lafayette, the Metairie, the Girod, and St. Patrick’s. Here giant oaks, like bitterly beautiful dirges for the dead, fly their ghostly banners of moss…”

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), Moss Fingers, 1946, printed 1947, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, bequest of the artist, 1985.99. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Laughlin also wrote about photography, and often referenced a photographer’s ability to access a state of “hyper-reality” that transcended the camera’s documentary function.

The Camera’s Methods for Approaching Reality, by Clarence John Laughlin

(College Art Journal, Summer 1957, pp. 297-306)

Every good photograph embodies intensive and controlled seeing. From the methods and procedures of the creative photographer emerges a hyper-reality which transcends the recording function of the camera…

Every object – even the most commonplace—has many levels of meaning … and is enmeshed, to the sensitive mind, in the depths and jungles of psychological association and symbolic meaning. The camera can be used to probe these levels extending and intensifying our vision.

Further, [the camera] can deal with the incredible and inexhaustible magic of light—in a manner peculiar only to itself. The essential mystery of light lies at the very core of reality; it is, on the one hand, related to all living processes of which we know; on the other, it seems to be subtly fused with the very nature of time—through the camera, then, we can rediscover its magic and its mystery.

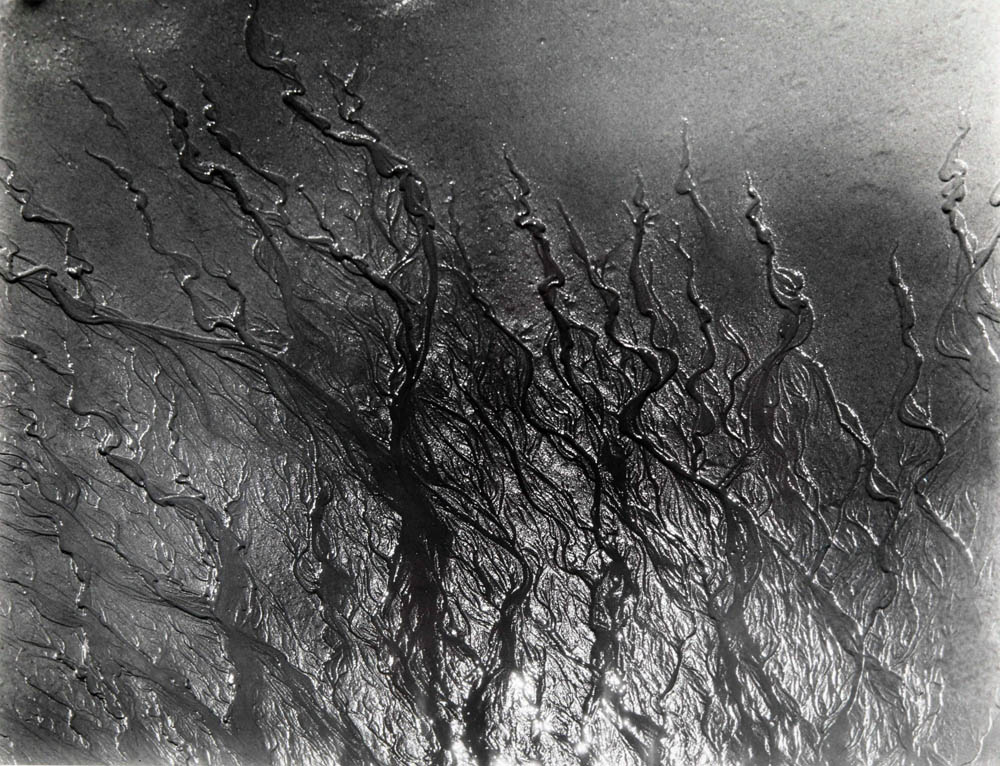

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), Black Flames in the Sand, 1952, printed 1979, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1981.84. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), A Living Glance Out of the Past, 1939, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Robert Yellowlees, 2015.44. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Clarence John Laughlin (American, 1905–1985), The Flower of Life, 1953, printed 1973, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet; her family members Josef, Jiri and Alma Beran Mann, all of whom perished in the Holocaust; and Sir Nicholas Winton, the British hero who orchestrated Charlotte’s escape with 669 Czechoslovakian children in 1939. © The Historic New Orleans Collection.

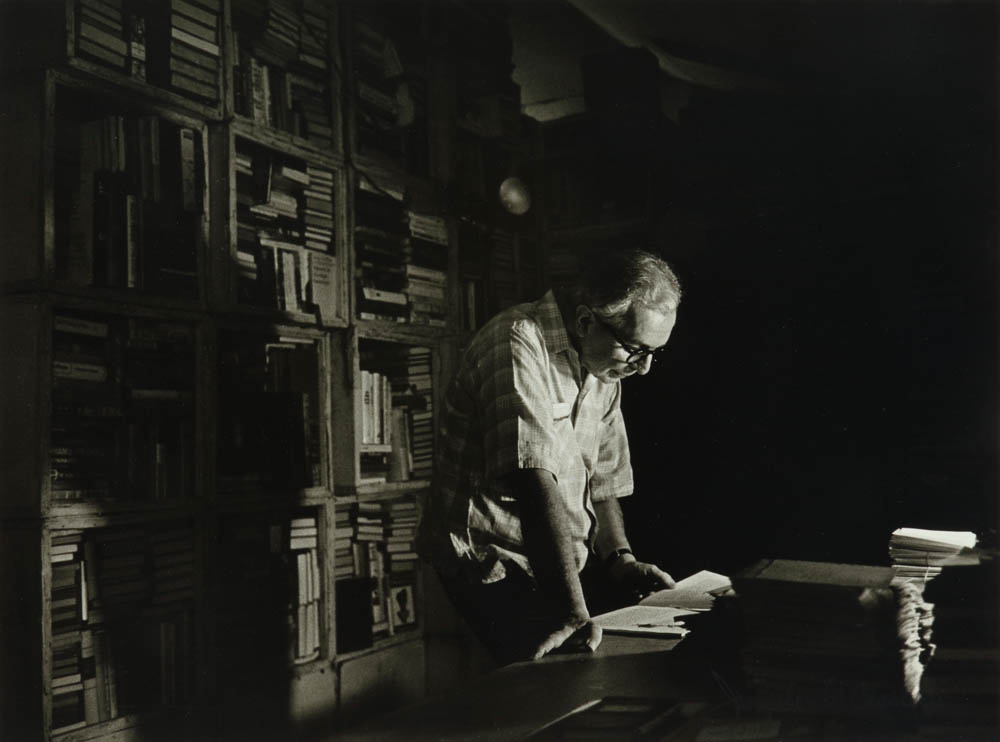

Joseph de Casseres (American, 1921–2006), Clarence John Laughlin, 1968, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase, 1978.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

The Aline Smithson Next Generation Award: Emilene OrozcoNovember 21st, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025

-

Josh Aronson: Florida BoysNovember 1st, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025