Facing Fire: Art, Wildfire, and the End of Nature in the New West

©Stuart Palley, El Portal Fire, Yosemite National Park, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2014, Courtesy of the artist

Natural disasters are ever increasing with climate change, and in California, we have been bracing ourselves for The Big One for decades. We are kept alert by tremors and shakers that seem to state,”Don’t get too comfortable”, but another disaster, insidious and onerous, has equaled in its horrors. Wildfires, raging out of control, spreading into towns and neighborhoods and wreaking havoc and significant loss are becoming an annual event.

Opening on February 22nd, UCR ARTS: California Museum of Photography will host the exhibition, Facing Fire:Art, Wildfire, and the End of Nature in the New West, curated by Douglas McCulloh. This massive exhibition looks at fire as omen and elemental force, as metaphor and personal experience. There will be an Opening Reception: February 29, 2020, 6:00 to 9:00 p.m.and the exhibition runs through August 9th, 2020. The artists include Noah Berger, Kevin Cooley, Josh Edelson, Samantha Fields, Jeff Frost, Luther Gerlach, Christian Houge, Richard Hutter, Christoph Kapeller, Benoit Malphettes,Anna Mayer , Cody Norris , Stuart Palley, Norma I. Quintana, Justin Sullivan, and Joan Wulf.

California’s diverse ecologies are fire-prone, fire-adapted, even fire-dependent. In the past two decades, however, West Coast wildfires have exploded in scale and severity. There is a powerful consensus that we have entered a new era—nature unbalanced, the end of the stable world. The artists of Facing Fire bring us incendiary work from active fire lines and psychic burn zones. Together, they face fire, sift its aftermath, and struggle with its implications.

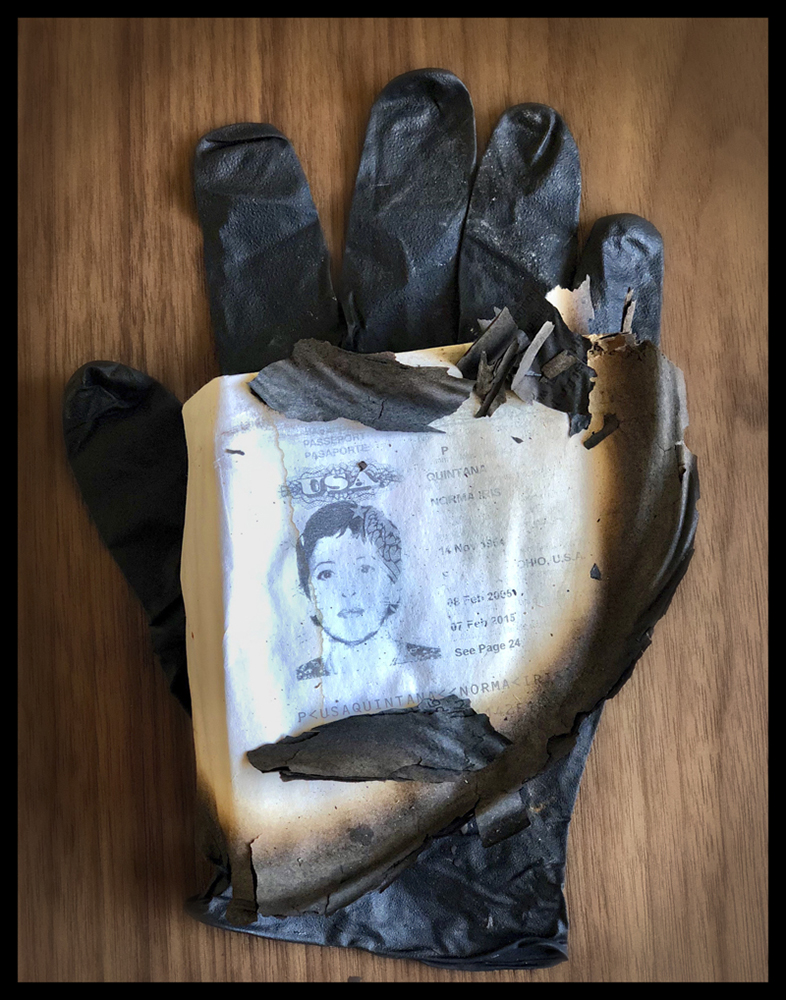

These artists are like poets who enter a burning building and bring back reports of majesty, fear, and flame. In 2008, Anna Mayer placed a dozen unfired ceramic sculptures into valleys and hillsides along the Malibu coastline. She intended them to be fired by wildfire. A decade later, the Woolsey Fire burned 96,000 acres, destroyed 1,643 structures, killed three people—and fired six of Mayer’s sculptural pieces. Norma I. Quintana, meanwhile, builds a photographic memorial to her house and studio consumed by Napa’s 2017 Atlas Peak firestorm. She registers her loss by documenting seventy charred objects sifted from the powdery ash—charcoal husks of cameras bodies, slumped remnants of rings, a bisque doll hand. In the end, though, what Quintana chronicles is spirit, resilience, and the abiding persistence of memory. In addition to artists obsessed with the elemental, the exhibition features work by California’s top acknowledged fire photography specialists.

Fire is natural in the western ecosystem, but it holds danger within it like a seed. California is built to burn, and it’s built to burn explosively. Extreme wildfire suppression is a hallmark of industrial society. Wildland fire is expunged, extinguished, overpowered. But nature has its own balances and counterbalances. Man is irrelevant. Suppression is unsustainable.

In the West, the results are clear. Sixteen of the twenty largest fires in California history occurred in the last twenty years. Six of the ten worst fires occurred in the eighteen months ending August 2019. They burned 3.65 million acres, destroyed 26,634 structures, and killed 137 people. In 2018 alone, California wildfires released more than forty-five million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. One major wildfire in California can set the emission gains of the entire state back to zero for the year.

©Christian Houge, Owl from the series Residence of Impermanence, Archival Pigment Print 2019, Courtesy of the artist

Meanwhile, Earth is heading into heat. “The year 1990 was the warmest year on record until 1991, which was equally hot,” states writer Elizabeth Kolbert. “Almost every subsequent year has been warmer still.” The hottest six years recorded on the planet are the last six years measured: 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. Human civilization emerged in a period of core climate stability. We are destroying our evolutionary birthplace. This is the scientific consensus: we have loosed an inexorable force. Change is locked in. Worldwide temperatures will continue to rise. Humanity is headed into a new climate regime.

Facing Fire is consequently pervaded by the uneasy sense that wildfire is a stand-in, a site of displacement for more immaterial fears, for the amorphous anxieties of the age. The psychic music of our time is discordant, distrustful, disintegrating. Wildfire, meanwhile, comes around with insistent seasonality. We face a darker more divisive time, so we gather again at the communal fire. Fire gives instability a physical form, inner decline an outward manifestation.

Fire as omen and elemental force, as metaphor and searing personal experience — these are the subjects explored by the artists of Facing Fire. California’s diverse ecologies are fire-prone, fire-adapted, even fire-dependent. In the past two decades, however, West Coast wildfires have exploded in scale and severity. There is a powerful consensus that we have entered a new era. The artists of Facing Fire bring us incendiary work from active fire lines and psychic burn zones. They face fire, sift its aftermath, and struggle with the implications.

©Noah Berger, Justin Sullivan shooting low, Camp Fire, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Associated Press

Noah Berger’s fire photography addiction has been fed by one hundred and fifty fires. “I got hooked on the experience of being out here,” he says. “It strips off the mundane layers of life.” Berger’s California wildfire photographs earned him a 2019 Pulitzer Prize nomination. An emergency fire shelter waits occupies the back seat of his Nissan Xterra. In the fire zone, Berger never turns the vehicle off. There might not be enough oxygen to start it again.

©Noah Berger, Kincade Fire, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Associated Press

Noah Berger is a freelance photographer who has spent twenty years covering California for editorial, corporate, and government clients. He works regularly for the Associated Press, the San Francisco Chronicle, Bloomberg News, The New York Times, and others. Berger started his editorial career at the University of California, Berkeley’s The Daily Californian and the Oakland Tribune. As he describes it, “It was through the student paper that I had my first ever assignment. I was eighteen years old and I completed five or six shoots which earned me more than $150. This was what got me hooked working for newspapers.”

Wildfires are a specialty, as are politics, natural disasters, and public protests. His work focuses on “staying open to new ways of shooting and thinking. . . . I have been a photographer for a long time, so when I take photographs, I imagine an audience residing in another city. I generally look for single images that convey the story as stand-alone photos.”

©Kevin Cooley, Controlled Burn #1, Archival Pigment Print 2013, Courtesy of the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

“Fire is a powerful natural force that we harness for the greater good. It is the only classical element we can create on demand, yet when out of control it has the potential for grave destruction.” – Kevin Cooley

The Los Angeles artist has spent years exploring the ancient classical elements—earth, water, air, fire, and aether—photographing coiling columns of dense smoke and producing Surreal images of California wildfires.

©Kevin Cooley, Swimming Pool, Woolsey Fire Archival Pigment Print 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles

For the past fifteen years, Kevin Cooley’s work has centered on a phenomenological, systems-based inquiry into humanity’s contemporary relationship with the five classical elements – earth, air, fire, water, and aether. The resulting photographs, videos, and public installations seek to decipher our complex, evolving relationships to nature, technology, and each other. He strives to challenge his assumptions and deepen his understanding of our environment and materiality. His newest work questions the long-term sustainability of present-day living and reveals the struggles—both practical and psychological—of inhabiting a planet we are slowly destroying.

Major installations in the public realm include Fallen Water commissioned by the City of Toronto, Remote Nation commissioned by Prudential Douglas Elliman for the High Line in New York City, and Nachfluge commissioned for airports across Norway by Avinor, the Norwegian Airport authority. Since 2014, he’s held solo exhibitions at Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco; Disjecta Contemporary Art Center, Portland; Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; Nevada Museum of Art, Reno; Pierogi, New York; Ryan Lee Gallery, New York; Savannah College of Art and Design; and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco.

Cooley’s work is represented in prominent public collections, including Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, New Hampshire; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts Houston; 21c Museum, Louisville; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; and the Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego.

Awards, grants, and residencies include: ArtPrize, Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Experimental Television Center, Aaron Siskind Foundation, Rema Hort Mann Foundation, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Headlands Center for the Arts, La Cité Internationale des Arts, LMCC Workspace, and The Arctic Circle.

He lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

©Josh Edelson, Fallen power lines on burned vehicles, Paradise, California; Camp Fire, November 10, 2018, Dye sublimation print on aluminum, Courtesy of Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images

Josh Edelson thinks humanity needs a reset. “Natural disasters are dangerous, fast, and powerful, beyond man’s control. They make you feel humble, very, very small, and that seems very important at this moment. Natural disasters are the core driver of why I do photojournalism. It seems important to bear witness to the actual lack of control of almighty humans.”

Josh Edelson is a freelance photojournalist for international news wires and newspapers including the Associated Press, AFP/Getty Images, the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post. He placed second in the National Press Photographers Association Best of Photojournalism competition for a wildfire image taken on assignment for the Associated Press and as well as honorable mentions for two other images from the same organization.

Edelson is especially passionate and driven to photograph natural disasters and has covered dozens of wildfires, protests, flooding, and tornadoes, as well as the occasional CEO and celebrity portrait. His commercial clients include Google, Facebook, Salesforce, Apple, LinkedIn, the government of Ireland, the government of Dubai, and AirBNB.

©Samantha Fields, Containment Series No. 64, Acylic on Canvas over Board, 2009-2010, Courtesy of Traywick Contemporary, Berkeley, California

Samantha Fields presents the viewer with images of mysterious manufacture. “I paint atmosphere with atmosphere,” she says. There is no touch of hand, no texture of paint. She sprays coat after coat of vaporized acrylic paint onto super smooth canvas. The wildfire paintings are based on her own photographs. “It takes hundreds of layers to create the paintings, which while photographic, deny the accuracy of that medium upon closer inspection.”

©Samantha Fields, Triangle Complex Fire (Diamond Bar) as Seen from Krai’s Old Neighborhood, Acylic on Canvas over Board, 2009, Courtesy of Traywick Contemporary, Berkeley, California

Samantha Fields was born in Cleveland, Ohio and holds a bachelor of fine arts from the Cleveland Institute of Art, and a master of fine arts from Cranbrook Academy of Art. She currently lives and works in Los Angeles where she is a professor of art at California State University, Northridge.

She has received numerous awards, including the City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Grant. She has an extensive exhibition history, including shows at Western Project, Los Angeles; Kim Light/LIGHTBOX Gallery, Los Angeles; Melanee Cooper Gallery, Chicago; Solway Jones Gallery, Los Angeles; PØST Gallery, Los Angeles; Domestic Setting Gallery, Mar Vista, California; Susanne Hilberry Gallery, Detroit; Lemberg Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan; and Engholm Englehorn Galerie, Vienna, Austria. She is represented by Traywick Contemporary in Berkeley, California.

Her work has been collected by and exhibited at noted public institutions such as the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento; Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum at California State University, Long Beach; Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills; Jones Center of The Contemporary Austin; and the Irvine Fine Arts Center.

She has appeared on The Conversation podcast, and is a regular co-host on the Art For Your Ear podcast with Danielle Krysa. Her work has been reviewed in the Los Angeles Times, ZYZZYVA, ArtWeek, Art in America, art ltd., Artillery, The Detroit News, the Detroit Free Press, and The Plain Dealer.

Jeff Frost operates along what he calls the “creation–destruction” spectrum. His twenty-four minute video piece, California on Fire, was a five-year obsession. Frost took extreme firefighter training and gained full access to more than seventy fires across the state. He came away with thirty terabytes of image and sound and some 350,000 photographs.

Jeff Frost’s primary mediums, time and sound, are expressed most often through a number of sub-mediums including painting, photography, video, and installation. Nearly all of the above are combined into short films that explore the spectrum of creation and destruction.

Frost’s work has been shown at the Desert X 2019 parallel installations California on Fire, Camel Stable, Palm Desert, and Paradise: Parallax, BoxoHOUSE, Joshua Tree. Other exhibitions include Los Angeles Art Association Open curated by Leslie Jones of LACMA; the Palm Springs Photo Festival, Palm Springs Art Museum; TEDxCERN, Center for European Nuclear Research, Geneva, Switzerland where he also has a print on permanent display; and Wild Blue Yonder, LAX. He has been selected for the 2019 NordicLA residency at the ACE Hotel in Palm Springs. In 2020 he will have a new painting film, GO HOME, at the Museum of Art and History (MOAH), Lancaster, and his long-term project California on Fire will appear in the touring show, Environmental Impact II. He was a subject of the 2017 Netflix docuseries, Fire Chasers. That same year he contributed to the National Geographic series, One Strange Rock.

Jeff Frost has been featured in numerous online publications and television programs including PBS Newshour, TIME, Artnet, and American Photo.

Luther Gerlach roamed the massive 2017 Thomas Fire burn area with an 8 x 10 view camera. He collected alkaline ash and sulfur-laden water from natural hot springs at the fire’s Ventura County origin point. As the prints develop, he applies slurries of ash and acidic water. They conjure a unique swirl of ghostly effects. It’s as if the chemical catalysts “carry a memory of fire,” states the artist.

Luther Gerlach works in a variety of historic photographic processes, highlighting the hand-made, tactile connection between the artist and his work and the role of constraint in creative production. Known for portraits and urban scenes of downtown Los Angeles in his early career, more recently Gerlach has pioneered the re-emergence of plein air wet plate collodion landscapes. His detailed images of the natural world, particularly the trees, seaweeds, and grasses of Southern California emphasize pure light and line, endowing his images with a subtly abstract quality.

Gerlach apprenticed with Brett Weston in Carmel and Hawaii in the 1980’s before learning the wet plate process in which he still works today. He lectures and leads demonstrations at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Gerlach has exhibited at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art; the Ventura Museum of Art; the Schacknow Museum of Fine Art, Miami; the Denver Art Museum; and the Palace of the Governors, Santa Fe. Selected permanent collections include the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; and the Wilson Centre for Photography, London, England, among others.

The artist lives and works in Hampton, Connecticut.

©Christian Houge, Puma from the series Residence of Impermanence,Archival Pigment Print 2019, Courtesy of the artist

Christian Houge spent seven years collecting taxidermied animals, often rare trophy specimens. He mounts them on English wallpapers from the era of colonial conquest. Then he burns them. “Conceptually, the series comprise a performance, a totemic ritual. Existentially, I’m setting the animal free, I’m closing the circle. And physically, I’m destroying an object and thereby removing it from the market.” The project, of course, also casts light on worldwide issues of environment and climate.

For twenty years, Norwegian artist Christian Houge has made photographs that explore the relationship and conflict between man and nature. “Man’s ego, consumer society, identity, and the last remnants of pure nature are recurring elements in all my work. My photographs are often very visual, but at the same time disquieting or uneasy. An underlying feeling of that which is lost often plays an important role.” Houge intends to make work which “emanates cognitive dissonance in the viewer to reveal deeper truths.”

Hogue has exhibited extensively in galleries and museums in his native Norway as well as in the United States, England, France, and China. His work has twice been nominated for the Prix Pictet, the global award for photography and sustainability, and his Arctic Technology series was shortlisted in 2005 for the BMW Prize at Paris Photo. In 2015, his Paradise Lost project was shown in three Chinese cities, including the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing. Residence of Impermanence, which explores our disconnected relationship with nature, has been shown at three museums.

Hogue’s deepest recurring theme is man’s action and position in the environment upon which humanity depends. “For me, photography is not just about stopping time, it is a window to look through. I look into myself in a way I never could have dreamed, and I invite others to look into themselves as well.”

©Richard Hutter, Microscopic Appropriation No. 6025, Archival Pigment Print, undated, Courtesy of the artist

Richard Hutter was shooting photographs from a U.S. Marine Corps helicopter when the craft crashed on El Toro Peak near Camp Pendleton. The disintegrating main rotor came through the front bubble and killed the pilot. A landing strut punched through the wing fuel tank. “They said I was so soaked in jet fuel that I was actually burning underneath my Nomex fireproof flight suit.” In the years since, Hutter has made photographs that appear distressed, dissolved, eroded. Many seem linked to fire, to trauma, to retrieving the self from the edge of obliteration.

“Fire is a nasty bitch,” writes Richard Hutter. “I know, I’ve had fire’s flames engulf me.” Hutter, a photographer, was in a severe Marine Corps helicopter crash, the craft rolling end over end, landing struts punching through the fuel tanks. “My world is nothing but fire and flame, an intimate procedure that bubbles and bursts my skin.”

“The docs estimate I was in the flames for over a minute. My parents are told I will die. Medics call me ‘Crispy Critter.’ But the docs do not know that Marine Corps sergeants are the toughest, baddest animals that walk the planet. Fourteen months later, I exit the hospital and return to my photographic life.”

With the exception of fire and flame, Hutter’s biography is similar to many photographers born and raised in the analog era. He was fascinated by his parent’s Kodak Duaflex twin lens box camera. He took photographs through a microscope and took top prize at the junior high science fair. He was a newspaper and yearbook photographer in high school.

Hutter holds multiple degrees: a bachelor of fine arts in photography from the San Francisco Art Institute, a master of fine arts in photography from the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), and master and master of fine arts degrees in English and Literature from Chapman University.

©Christoph Kapeller, Woolsey Fire, 2018, from the series, Solid State Remains, Archival Pigment Print mounted on Dibond 2018, Courtesy of the artist

Christoph Kapeller’s initial attraction was the beauty of burned landscapes. Kapeller was born in Austria and spent winters skiing in the Alps before becoming a founding partner of the prestigious international architecture firm Snøhetta. He equates natural wildfire with the transfiguring effects of a massive first snowfall—but it’s an inverse. “Forbidding, blackened, destructive, not at all inviting. But similarly simplified and transformed.”

Christoph Kapeller is an Austrian born architect and artist who lives and works in Los Angeles. He was a founding partner of the Norwegian firm Snøhetta after having been awarded the First Prize in the international architectural competition for the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the new library of Alexandria, Egypt in 1989. During the course of the project, Kapeller spent eight years in Egypt overseeing the design and construction of this world-renowned, UNESCO-sponsored project.

Since his relocation to Los Angeles, his studio has won numerous prizes and awards in international architectural design competitions. Among others: the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004; finalist for the Aomori Northern Housing Complex, Aomori, Japan, in 2002; a meritorious award for the Malama Learning Center competition, Hawaii, in 2004; and a third prize in the Stadt Schloss Holte-Stukenbrock master plan competition, Germany in 2012.

In addition to his architectural practice, Kapeller has exhibited art and photography projects in a number of group shows: an open air installation at FREEZE–Anchorage in collaboration with Lita Albuquerque and BuroHappold Engineering, 2009; Chengdu Speculative Mapping, a video installation at the Chengdu Biennale 2011; Yedoma, a sculpture and photo installation at the 2016 exhibition View From up Here: The Arctic at the Center of the World in 2016 at the Anchorage Museum; The Sacred, a group show at the Lightbox Gallery, Astoria, Oregon, curated by Robert Adams in 2018; and the juror’s award at Extending Tradition 2 at the same gallery in 2019, curated by Stu Levy.

©Anna Mayer, Recovering Wildfire-fired Ceramic, Archival Pigment Print (Photo: Poppy Coles) 2018, Courtesy of the artist

Anna Mayer placed a dozen unfired ceramic sculptures into valleys and hillsides along the Malibu coastline in September, 2008. The artist intended them to be fired by wildfire. They were raw, crumpled, torso-sized slabs inscribed with text. For ten years, the work existed as a proposition, a conceptual gesture. In November 2018, the Woolsey Fire burned 96,000 acres, destroyed 1,643 structures, killed three people—and fired six of Mayer’s sculptural pieces. She recovered four.

6

©Anna Mayer, Old Epic Stories Handed Down Into the Hands of Storytellers (Charmlee Wilderness), Wildfire-fired ceramic, 2008-2018, Courtesy of the artist

Anna Mayer’s art practice is sculptural and social, with an emphasis on hand-built ceramics and enacting formative site-specific projects in Southern California. Her methodology emerges from an interest in the relationship between speech and consciousness and extensive engagement with the various social practices and feminist histories of Los Angeles.

Mayer recently had solo exhibitions at AWHRHWAR, Adjunct Positions, and A-B Projects, all in Los Angeles. In 2020 she will mount a large-scale solo show at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Selected exhibitions include Night Gallery, Los Angeles; Galerie Catherine Bastide, Brussels, Belgium; Ballroom Marfa; Kendall Koppe, Glasgow, Scotland; Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Klaus Von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York; Machine Project, Los Angeles; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Luckman Fine Arts Complex at California State University, Los Angeles; Glasgow International; and Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont. Mayer’s writing has appeared in X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly and ART21 Magazine, as well as in her artist’s book, Loose Lips Loosen Lips.

She is currently assistant professor of sculpture at the University of Houston, where she oversees the ceramics program. Mayer was assistant director of the LA-based Institute For Figuring, a “feral organization,” from 2009–2018. Since 2015, Mayer has had an ongoing collaborative practice with Jemima Wyman, called CamLab, which has staged events and exhibited in Los Angeles at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Hammer Museum, and Wildness at the Silver Platter, and in Pasadena at the Armory Center for the Arts. In Fall 2015, CamLab was the Wanlass Artist in Residence at Occidental College and in 2017 received a fellowship from the Woman’s Building and Metabolic Studio in Los Angeles.

©Stuart Palley, Burned Joshua Trees, Erskine Fire, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2016, Courtesy of the artist

Stuart Palley is deeply aware of the issues. “Wildfires are the most acute effect of drought, climate change, and human sprawl in California.” But from the start he has also aimed his cameras at something more ethereal—the effects produced by long exposures at night. To date, Palley has photographed more than hundred fires. He opens his shutter for a second to four minutes or more. He bathes the sensors in the unique radiant light of fire and moon, smoke and stars.

©Stuart Palley, Stuart-Fire Over Half Dome Meadow Fire , Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2014, Courtesy of the artist

Stuart Palley is based in Southern California and specializes in environmental, art, editorial, and commercial/corporate subjects. Stuart received a bachelor of business administration and bachelor of arts from Southern Methodist University, studying finance and history and minoring in photography and human rights. He holds a master’s in photojournalism from the University of Missouri.

His recent work on wildfires, Terra Flamma: Wildfires at Night, focuses on documenting wildfire, the most acute effect of California’s ongoing drought, through long exposures made at night. Over the past five years Palley has photographed almost one hundred wildfires in the state and has formal wildland fire training. The project has been featured in dozens of media outlets across the globe and was recognized as a finalist in the Environmental Vision category of the prestigious Pictures of the Year International photography competition in 2016. The project also received awards in 2015 and 2018. Terra Flamma is a visual commentary on the collision of man and nature, on fire and climate change. Each image seeks to place fire in its geographic context whether it is a blaze on the edge of urban Los Angeles or far into the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Most recently, work from the project was published as part of an article on electronic surveillance entitled “We Are Watching You” in the February 2018 issue of National Geographic Magazine.

Born and raised in Southern California, Palley has photographed for National Geographic Magazine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His work has also appeared in TIME, WIRED, and New York Magazine.

Norma I. Quintana’s home was destroyed the night of October 8, 2017 by the Atlas Peak Fire. The family had five minutes to flee. As she sifted the ashes in following weeks, the artist came to regard the surviving fire fragments not as mere objects, but as containers of memory. She developed a ritual of salvage, survival, and recollection. She placed each recovered remnant of her previous life on the back of a rubber glove employed to comb the wreckage and she used her iPhone X to make photographs.

Norma I. Quintana earned a master’s in social sciences from Case Western Reserve University and worked in human resources during her corporate career. Quintana’s photographic vocation began in 1999 and she has studied with Mary Ellen Mark and Shelby Lee Adams. Working in the tradition of social documentary, she primarily uses film and natural light. Her portrait series Forget Me Not has been exhibited in California and Washington, DC while her project Circus: A Traveling Life has traveled to nine venues and was published in 2014 as a monograph by Damiani Editore and distributed by Distributed Art Publishers.

Quintana has lectured nationally at Stanford University; University of California, Los Angeles; American University, Pennsylvania State University, and B&H Photo in New York City, and internationally in Madrid, Spain. Her photographic series Forage From Fire evolved after she lost her home and studio during the devastating 2017 Atlas Peak Fire in Northern California. The series was first presented as a solo exhibition at SF Camerawork in October 2018, and in a group exhibition at Sonoma Valley Museum of Art.

Quintana is a founding board member of PhotoAlliance, a San Francisco organization dedicated to supporting the understanding, appreciation and creation of contemporary photography. In 2020, she will travel to Puerto Rico to document the lives of coffee farmers.

©Justin Sullivan, Camp Fire, Paradise, California, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Getty Images

Justin Sullivan has photographed wildfires since 1998. “I’m a journalist. I don’t know whether it’s global warming or not. I’m not paid to decide that. But I will say that these fires have gone from pretty serious to insane.” Sullivan commonly teams with Noah Berger and Josh Edelson. The partnership is part camaraderie, part safety. “We all have a deep relationship with wildfires. We go deeper. We spend more time. But it’s inherently dangerous. It could cost you your life, so it’s safer to travel together.”

©Justin Sullivan, Kincade Fire, Geyserville, California, Dye sublimation print on aluminum 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Getty Images

Justin Sullivan is a staff photographer with Getty Images based in San Francisco, California.

“In the 1990s I was studying to be a paramedic,” he explained. “But one day I made the decision to pursue photography instead. I had been taking pictures during ‘ride-alongs’ as an EMT, and found that I enjoyed the rush of not only racing to wherever the action was, but capturing those moments, too.” In the two decades since then, Sullivan has covered more than a dozen wildfires, most of them in California, many of them among the deadliest and most destructive on record.

His assignments have also included a wide range of stories from national political campaigns and the California to international conflicts. Justin’s award-winning work has appeared in magazines and newspapers around the world. He is a three-time San Francisco Bay Area Press Photographer of the Year.

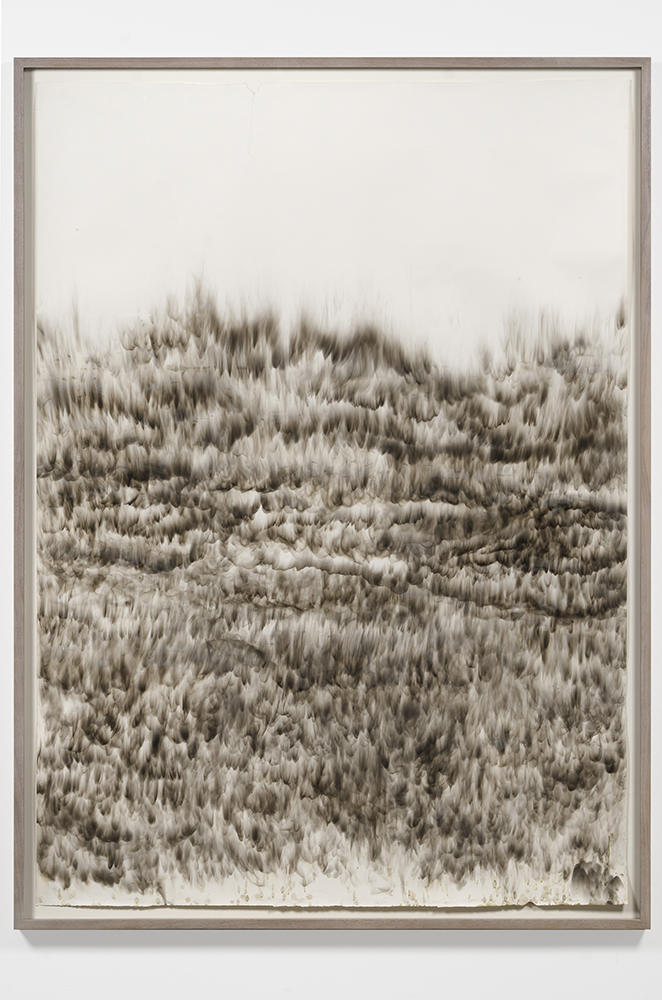

Joan Wulf uses fire to depict fire. The artist’s subject and the studio materials are one and the same. Tongues of smoke capture the flicker of flame, the touch of wind. To portray nature’s most basic states, Wulf has burned, torched, sprayed, oxidized, ripped, crushed, and bent. She has set alight and quenched in water. Such touchless drawing with smoke and fire is known as “fumage,”a technique explored by the Surrealists.

Joan Wulf is a painter and mixed media artist based in Los Angeles who reductively explores the nexus of nature and science. She focuses in particular on the elements: water, wood, fire, earth, and metal. Once points of departure for her paintings, the elements have evolved into “collaborators” in Wulf’s studio practice. She has variously burned, torched, sprayed, oxidized, ripped, glued, and bent materials in her quest to distill nature to its most basic state.

Wulf holds a bachelor of science from the University of California, Davis and a bachelor and master of fine arts in painting from the San Francisco Art Institute. A California native, Wulf lived and worked in San Francisco until relocating to Los Angeles in 2009. She has shown widely in group and solo exhibitions, including Themes+Projects Gallery, San Francisco; the José Drudis-Biada Art Gallery, Mount Saint Mary’s University, Los Angeles; Villa Di Donato, Naples, Italy; and the Santa Monica Museum of Art. Her work can be found in many public and private collections throughout the United States and Europe. She is a member of the Los Angeles Art Association.

Facing Fire: Art, Wildfire, and the End of Nature in the New West

Curator’s Essay by Douglas McCulloh

“To those who do not know the world is on fire, I have nothing to say.” —Bertolt Brecht

Fire as Metaphor

Fire is mankind’s root metaphor. Fire wants to spread. So, too, does the meaning of fire.

Fire is passion and punishment. It is lust and the lake of fire. It is the spark of inspiration and the blaze of anger. Fire is passage, purification, and the funeral pyre.

“It shines in Paradise. It burns in Hell,” writes French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. “It is gentleness and torture. It is the cooking hearth and the apocalypse… It is well-being and it is respect. It is a teacher and a terrible divinity.” Fire is myth, fire is power, fire is science. Fire is intimate and fire is universal.

Fire is elemental. Nonetheless, human beings transmute fire into idea. Yet the idea we call fire is as shapeshifting as fire itself. We project its burning light into our lives.

Fire cannot be conceived of simply. It is a mystery and one which art can only be asked to deepen.

Mythology

Fire burns deep. Prometheus “invented all the arts of man” by granting “bright and dancing fire” to humanity, writes Aeschylus. Rome’s oldest shrine honors Vesta, goddess of the hearth. The Bible’s first manifestations of Yahweh occur through smoke and flame. Fire rites remain, shrunk to votive candles and eternal flames.

Modern capitalism is a fire-driven ecosystem. Globe-straddling corporations extract fire’s fuels, accruing wealth, hegemony, and incalculable power. Fire circulates as fluid, gas, coal-black carbon. It is harnessed within the dedicated chambers of a billion specialized machines. Fire’s power flows vast distances over the electrical grid. And “firepower” remains the measure of military strength.

Fire has ever been fire and yet not fire, the gift and the curse of the gods. Fire has been hearth, home, destruction, danger, warmth, death. Now, in the Anthropocene, fire represents something new—mankind the meddler, nature unbalanced, alarm, warning, turning point, catastrophe, shrouds of smoke, implacable forces loosed, the end of the stable world.

Fire in Our Minds

Mankind lets fire speak its full range of tongues. We’ve carried it around the planet and it has carried us. We turn fire into dynamos and conflagrations. We admire the brilliance of sparks as we sharpen our weapons. We tend eternal flames for the heroic happy dead. We reduce fire to the ruby end of a cigarette and suck it into ourselves, like inhaling a mythology.

Increasingly, we carry fire in our minds. Which is to say we consume ourselves, and we celebrate the immolation.

“Thus saith the Lord God: “Behold, I will kindle a fire in you, and it shall devour every green tree and every dry tree in you; the blazing flame shall not be quenched, and all the faces from the south to the north shall be scorched by it.”—Ezekiel 20:47

Elemental

We call fire forth. We cannot similarly summon floods, earthquakes, droughts, or hurricanes.

Fire is a fundamental force. A runaway fracturing of molecular bonds that seems a direct, unmediated expression of nature. For all that, we make it shimmer with meaning. Fire transforms, but we alone transform fire.

Like a deluge, a hurricane, a cataclysmic earthquake, fire is elemental. Yet we have domesticated this primal force, brought it inside to warm the hearth. But fire’s threat remains. Every glade is laid for a bonfire. Every flickering flame, the source of a firestorm.

The roar of flame, the silence of ash. The burnt offering. Equalized by fire, equalized as ash.

Amorphous Anxiety

“There is infinite hope, only not for us.”—Franz Kafka

We have entered a new state of perpetual threat. The ideal emblem of this condition is fire. Burn that into your memory.

Wildfire is a stand-in, a site of displacement for more immaterial fears, for the amorphous anxieties of the age.

The psychic music of our time is discordant, distrustful, disintegrating. Wildfire, meanwhile, comes around with insistent seasonality. It is a fierce refrain. It is the terminal dystopian metaphor: uncontrollable, deadly, devouring. Wildfire represents the ultimate consuming apocalypse. Go ahead, stare into the fire.

Unlike the slow degradation of ecosystems, the near-invisible harms of economic imbalance, the erosion of norms, fire is fiercely visual. When fear and anger rise, we see nothing. When flames engulf a mountainside, a valley, a neighborhood, photographers flock and news helicopters stream a live feed.

We face a darker more divisive time, so we gather again at the communal fire. Fire gives instability a physical form, inner decline an outward manifestation.

Fire and Humanity

Every human society has possessed fire, tended it, treasured it. We carry torches and gather fuel. Hearths brand our earliest caves. We rendered extinct aurochs, mammoths, and cave hyenas in charcoal at Lascaux and Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc.

“Fire tracks, as perhaps no other index can, the awesome, stumbling, unexpected, implacable, fascinating course of humanity’s ecological agency,” writes wildfire historian Stephen Pyne. “The story of one cannot be told except through the other.”

Fire empowered humanity, but it is equally the case that humanity freed flame. Mankind touched every place it visited with fire. The hominid diaspora is marked by charcoal: the hearth fire; the burned bones of prey; the carbon black of ritual cremation; the firing of forest and steppe, glade and grassland. Fire and humanity propelled each other around the planet.

Fire Suppression

Extreme wildfire suppression is a hallmark of industrial society. Wildland fire is expunged, extinguished, overpowered.

But nature has its own balances and counterbalances. Man is irrelevant. Suppression is unsustainable. “Throughout the twentieth century, federal policy focused on putting out fires as quickly as possible,” writes Nicola Twilley. “An unintended consequence of this strategy has been a disastrous buildup in forest density, which has provided the fuel for so-called ‘megafires.’”

As stakes rise and fuel loads build, firefighting efforts are doubled and redoubled. The result is a classic Darwinian system—we select for bigger, tougher fires. Every feeble wildfire that can be extinguished is killed. When fuel is slight or damp, the fire is killed. When wind is calm or terrain flat, the fire is killed. Meanwhile, fuel loads build: ten years, thirty, one hundred. Finally, the fittest fires arrive. Hot and dry, high wind, inaccessible ignitions. When these fires emerge—and they inevitably, inescapably, do—they burn with unnatural ferocity. We breed monsters.

Built to Burn

Fire is natural in the western ecosystem, but it holds danger within it like a seed. In the hills and mountains and windy passes of California, an absence of fire portends the coming of flame just as a flash of lightning presages the boom of thunder.

“California is built to burn. And it’s built to burn explosively,” comments fire historian Stephen Pyne. “And almost everything people have done over the last 150 years has aggravated those conditions. And now climate change is acting as a performance enhancer — if you will — on top of that, and making it worse.”

California and Fire

Between 1990 and 2010, home building in the wildland-urban interface increased forty-one percent nationwide—and now totals over forty-one million homes.

Sixteen of the twenty largest fires in California history occurred in the last twenty years. Six of the ten worst fires occurred in the eighteen months ending August 2019. They burned 3.65 million acres, destroyed 26,634 structures, and killed 137 people.

In 2018 alone, California wildfires released more than forty-five million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. One major wildfire in California can set the emission gains of the entire state back to zero for the year.

Heading into Heat

“…his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.”

—Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

Earth is heading into heat. “The year 1990 was the warmest year on record until 1991, which was equally hot,” states writer Elizabeth Kolbert. “Almost every subsequent year has been warmer still.” The hottest six years recorded on the planet are the last six years measured: 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Human civilization emerged in a period of core climate stability. We are destroying our evolutionary birthplace. This is the scientific consensus: we have loosed an inexorable force. Change is locked in. Worldwide temperatures will continue to rise. Humanity is headed into a new climate regime. Mankind’s cradle is on fire.

Wildfire Future

Wildfire lights our way as earth becomes a shipwreck.

Wildfire consequences are cumulative. Earth is a complex interconnected ecological system. Set a fire and feel the far-flung flickering effects. Airborne soot and ash darken northern ice sheets. Blackened ice absorbs more solar radiation and melts faster. Sea levels rise and warm, spinning off wetter storms that drown and scour fire-denuded slopes. Super storms deluge vulnerable coasts. Beyond that, humanity is expanding fire’s reign. We raid a hundred million years of stored carbon—coal, oil, and gas— to make a world that runs on fire.

A destabilized climate arcs into fire. The total area burned in a single year by wildfires in the United States has only exceeded 13,900 square miles, an area larger than Belgium, four times since the middle of last century. All four have happened in the past ten years.

Look forward to fiercer, faster, more destructive wildfires for the rest of your life. Walk into bright, mean fire. See if you come out alive.

My hour is almost come,

When I to sulphurous and tormenting flames

Must render up myself.

—Shakespeare, Hamlet

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025