Leah Schretenthaler: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable Mention

It is with great pleasure that we announce the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Leah Schretenthaler. She was selected for her outstanding project, The Invasive Species of the Built Environment. She is working towards her MFA at University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The jurors included Guanyu Xu – 2019 Student Prize Winner, Zora Murff- 2018 Student Prize Winner, Shawn Bush – 2017 Student Prize Winner, Drew Nikonowicz – 2016 Student Prize Winner, Elizabeth Moran – 2013 Student Prize Winner, Aline Smithson – Lenscratch Founder & Editor in Chief, Brennan Booker – Lenscratch Director of Special Projects, and Daniel George – Lenscratch Submissions Editor. We had a record number of submissions and the competition was fierce.

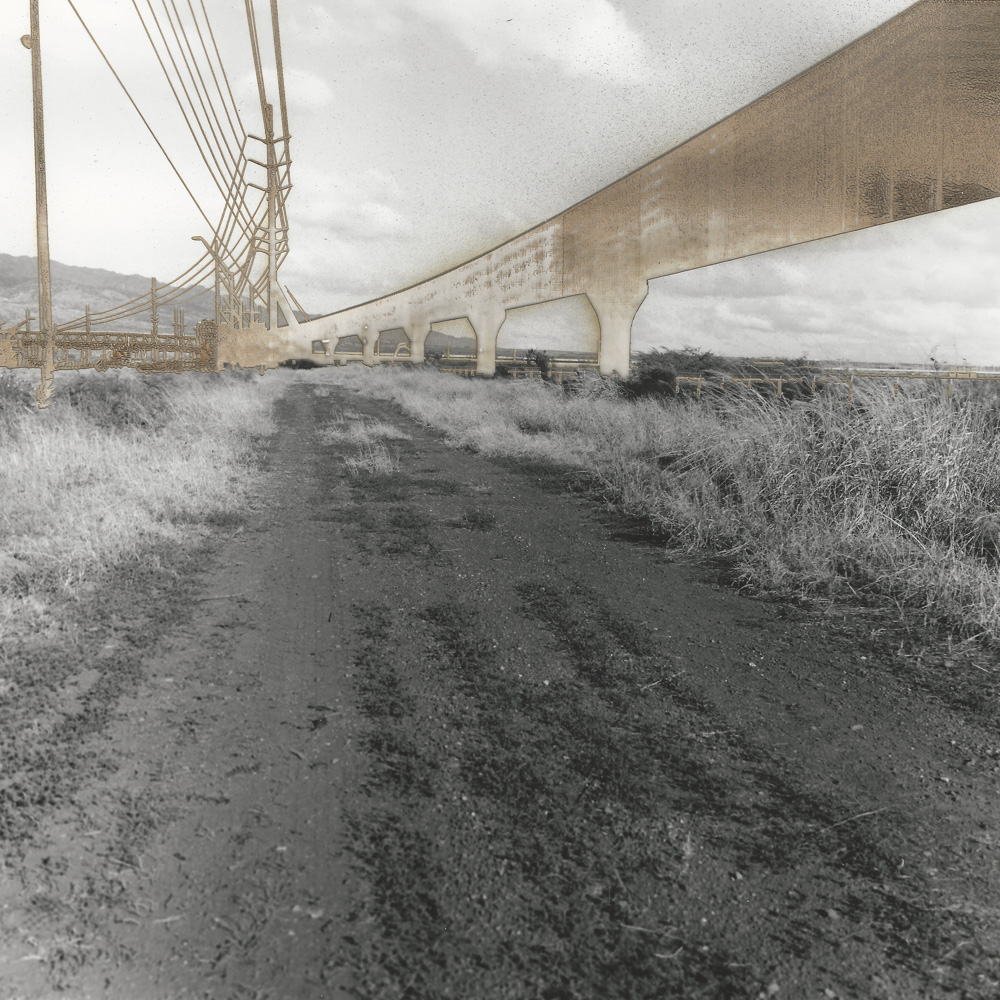

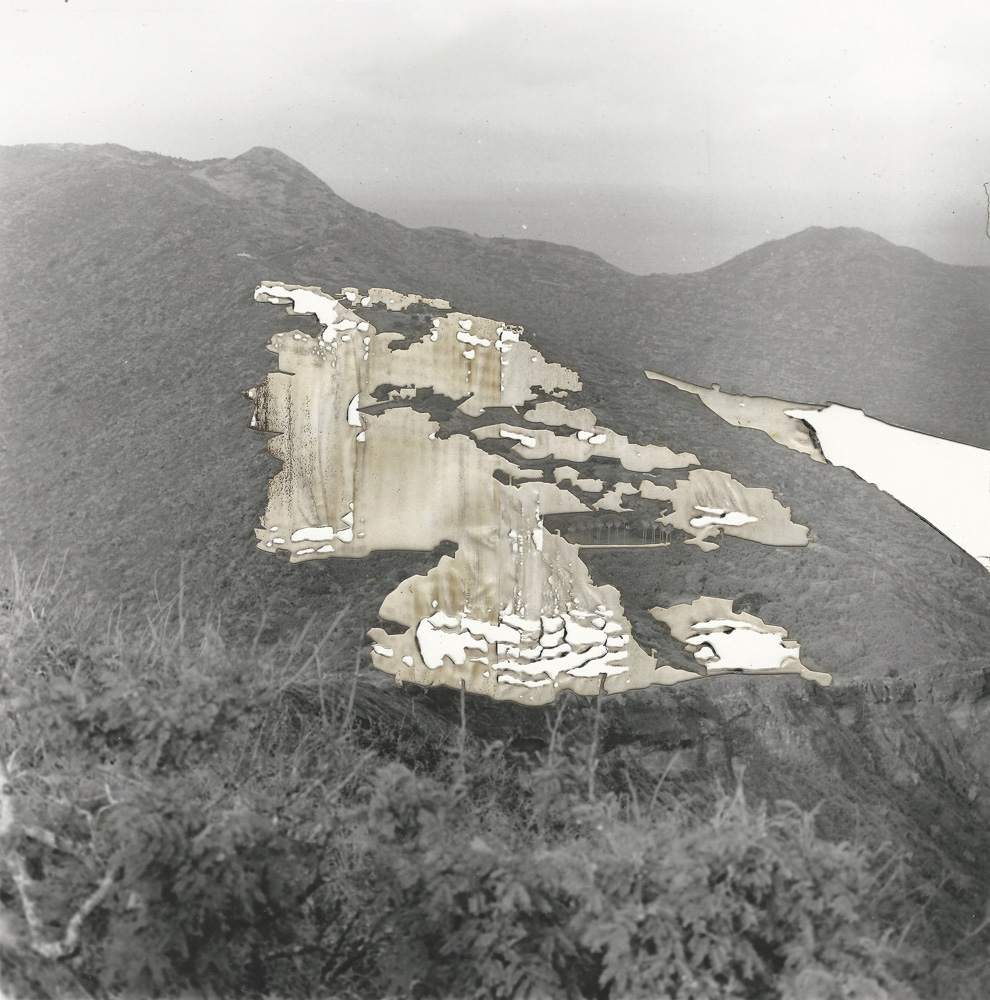

Leah’s photographs imagine a Hawaiian landscape devoid of human structures. However, rather than pointing her camera in a direction that avoids these things altogether (a simple solution in such an attractive place), she confronts them head on to describe the social, environmental, and visual implications of a society hell-bent on infrastructural progress. Her process involves physically removing these monuments with a laser cutter. In their place, we are left with a disfigured reminder of our offenses.

Leah Schretenthaler was born and raised in Hawaii. She has recently graduated with an MFA in photography from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Through her art practice, her research presents a connection between land and materiality. Her work has been displayed and published nationally and internationally. Most recently she has been named in LensCulture’s Emerging Talents of 2018, awarded 2nd in Sony World Photography Awards, and was also awarded the Rhonda Wilson Award from Klompching Gallery in FRESH2019.

The Invasive Species of the Built Environment

The Invasive Species of the Built Environment

The land of Hawaii is vast, luxurious, and idyllic but past the wanderlust images the land is very controversial. The growing population and tourism continues to threaten the space and its ability to accommodate all the occupants. From the research telescopes on the mountain of Maunakea on the Big Island, to the crumbling rail project on Oahu believed to fix the traffic problem, these infrastructures have augmented the land. The industrial growth happening in Hawaii goes beyond simply manipulating the landscape; it destroys the historical records and spiritual places that have existed there for millions of years.

Through these photographs the attention focuses on the spaces that these infrastructures impede on the natural environment, instead of colors of the idyllic Hawaii. Using silver gelatin prints which consist of selected, man made spaces that have attempted to be removed create a burnt and sometimes empty area. The use of a laser cutter to cut the structure from the landscape leaves scar upon the image. The removed spaces aid in seeing what Hawaii would be like without these impositions. These areas that have been removed from the images are not being replaced with anything, therefore communicates the natural impingement this structure has on the environment even if it were to be removed. However, the process of trying to remove these objects has weakened the paper and metaphorically weakened the landscape it is trying to depict. The areas that have not been completely removed leaves a faint and thin layer of paper residue. The structures still exist and can never be completely erased. However, it draws attention to what is becoming the built environment in Hawaii.

These invasive infrastructures have impinged on the natural environment. Although these images discuss visually the reality of Hawaii, it brings to light that this is not a one state problem. Much like the invasive species that we eradicate from our gardens and fields, so too should we approach these human invasions onto the landscape. No longer should humanity build for the sake of building; but should instead question the social and political concerns that exist in the natural world.

Daniel George: First off, I’d like to ask you a few questions about your project. Several years ago, I visited Hawaii for the first time and was profoundly impressed as I learned more about the native culture and its connectedness to the land—something that is generally lacking to the majority of us mainlanders. Could you talk more about your upbringing in Hawaii and how that has shaped your perceptions of the environment?

Leah Schretenthaler: I was brought up with a military mom but we only lived on a military base for a few years. This played a huge part in my upbringing. By not living on the base our entire childhood, my brother and I were able to have more freedom to explore the island with its many beaches, mountain hikes, and rainforest valleys. We were also able to hang out with friends without having to bring them on base.

Besides being free to roam the island, I grew up dancing hula. I was able to continue to dance hula at ‘Iolani School and my kumu (teacher) taught us different oli (chant), hula kahiko (ancient hula) and hula auana (modern hula) , as well as Tahitian dances. Since hula is Hawaii’s method of storytelling I learned even more about the history of Hawaii and the land that I call home.

Growing up, I also competed in sprint triathlons, oceans swims, and road races throughout the island. During these competitions I learned more about the terrain and weather on the different parts of the island.

Although all these experiences shaped my childhood I did not realize just how important everything was until I came back from my first semester of college. Growing up I always thought that I was missing out on experiences living on an island, but after I came back home from my first semester of college on the mainland, I realized how special and unique my upbringing was in shaping my perceptions of Oahu. I came back for Christmas break that year and saw places I hiked the previous summer had become a little more crowded. Each time I came back home over the years the trails and beaches I enjoyed were littered with people, trash, and structures to support the influx of people to these areas.

My childhood experiences helped shape my perceptions of the environment and when I left the islands to attend college on the mainland I realized just how important and informative my upbringing has been in shaping who I am today.

DG: I like that you use the word “scar” to describe the markings made by the laser, since it perfectly represents the improbability of the land ever fully healing from society’s destructive interventions. What brought you to utilize this technological process, and why did you feel it was most appropriate for your vision of the work?

LS: A laser etcher has been part of both me and my partner’s practice for 5 years. My partner and I were introduced to iron casting while attending the University of South Dakota. The university had just acquired a laser etcher and we wanted to make medallions for the Little Pour on the Prairie, an iron pout that takes place at the sculpture professor’s acreage. The medallions were laser etched in matboard and then we created a sand mold around the objects. Since iron can be 2200-2600 degrees Fahrenheit, the matboard burns away. After seeing great results my partner continued this process for his own work. But it would still be a few years before I would test it on photo paper.

When I first thought about using the laser on photo paper, it was to cut precise patterns in the paper. I used some old images from undergrad to do some tests. These tests turned out to be the turning point of the work. Because of the low settings I set on the laser, the laser did not burn all the way through the silver gelatin paper. I showed these tests to my partner and we were both fascinated with the materiality that was revealed through this process.

Quickly after these first tests were done, my partner and I left to go back home to Hawaii for the winter break. I began photographing the invasive builds knowing that I would be using the laser on these images once I got back to the mainland. Once we returned and I had developed, printed, and prepped the images I began laser etching larger areas than before. The image of the Honolulu Rail Transit in Pearl City was one of the first images I laser etched when we returned and it was this image that truly revealed the weakening of the paper. Before I went back home I had been following the construction of the rail but it was not until I was driving through Pearl City and Aiea that I realized how destructive it has been to the land and the people. After laser etching this image, I held up the piece and although the rail was no longer recognizable the structure was still evident as a disfigurement of the area.

DG: Your photographs highlight concerns over the natural environment as it relates to negligent expansion of the built environment. How would you like to see this contribute to the broader dialogue on the topic?

LS: While this work focuses on Hawaii, I know that this is not a one state problem. After living on the mainland for 10 years I have seen in a number of other states that buildings and projects continue to expand out into the seemingly unused land while other abandoned buildings continue to sit unoccupied. Our environment is a resource that is hard to revive once it has been damaged, especially if a project infringes upon sacred land or already endangered ecosystems. Going forward, my hope is that we truly consider the environmental, cultural, and spiritual history of the native land that is being impacted by this continual development.

DG: Now, here are a few things we like to ask all our Student Prize Winners. Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

LS: I was born and raised on the island of Oahu. After my mom retired as a Lieutenant Colonel, she made the choice to raise my brother and I on the island. I was lucky to be exposed to the many diverse cultures and landscapes. I learned to read the ocean currents and I became knowledgeable on the native plants during the many hikes. The diverse landscape of Oahu was my playground and I learned how to respect and love the place I call home. The cultures and landscape shaped who I am physically and mentally.

I got into photography when I attended Iolani School. My freshman year I was introduced to the darkroom and I fell in love with the material and the process. The next four years I traveled all over the island following my friends on hikes or to our favorite surf spots to capture our playgrounds.

DG: We are always considering what the next generation of photographers are thinking about in terms of their careers after graduation. Tell us what the photo world looks like from your perspective. What you need in terms of support from the photo world? How do you plan to make your mark? Have you discovered any new and innovative ways to present yourself as an artist?

LS: While in school I had the opportunity to make connections with the photo world and I am so happy I did not wait to explore this beautiful community. The photo world feels like an ohana, or family. The people I have been fortunate to meet have been so welcoming and giving with information and advice. As the new photographers join the photographic ohana I believe it is important that we all continue to provide advice and opportunities to one another. As someone still learning about the photographic world I have enjoyed the opportunities of the portfolio reviews such as Filter Photo Festival and FotoFest. Being able to travel to SPE National to talk and meet with new and old friends as well as traveling to New York to the KLOMPCHING Gallery to meet artists I have admired greatly over the years. These opportunities have been a huge support to me while I have been in school.

The past few years these entities have helped me get my start in the photo world, however, I do not feel like I have made my mark yet. To make my mark I plan to continue to submit to shows, competitions, and to continue to attend portfolio reviews and conferences. Through these different events I hope that I can continue to present myself and my work with aloha and represent my home state with pride.

DG: Again, congratulations on your Lenscratch Student Prize! What’s next for you? What are you thinking about and working on?

LS: The next step for me is to complete the Film Photo Award I received in the Fall of 2019. Due to the Coronavirus and the travel restrictions for Hawaii, I have been unable to travel back this past spring. I hope to travel back later this summer to complete the project. While I am on the mainland I am continuing to work on the sculptural work that has played a huge role in my research. For the past 6 years my partner and I have taken molds of the lava fields and we have been casting these impressions in bronze-aluminum as well as iron. These sculptures have also aided in my research for the sculptures that have been included in The Invasive Species of the Built Environment series.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amrita Stützle: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 29th, 2020

-

Leah Schretenthaler: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 28th, 2020

-

Hannah Altman: The 2020 Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 27th, 2020

-

Lindley Warren Mickunas: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 24th, 2020

-

William Camargo: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place WinnerJuly 23rd, 2020