Casey McGuire & Mark Schoon: The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial Casey McGuire and Mark Schoon.

Casey McGuire and Mark Schoon have been working as a collaborative team since 2015. Their collaborative work has been exhibited in exhibitions at 621 Gallery, Tallahassee, FL; Filter Space, Chicago, IL; SoHo Photo Gallery, NY; and Kai Lin Gallery, Atlanta. Work from their series “The Great Moon Hoax: Science and Recreation of the Artificial” have been published in The Photo Review, Fraction Magazine, and Manifest Gallery’s International Photography Annual.

McGuire received MFA in Sculpture from the University of Colorado, Boulder, in 2007. She was featured in the October 2009 issue of Sculpture Magazine. Her installations have been shown at Urban Institute for Contemporary Art, Grand Rapids, MI; Alexander Brest Gallery, Jacksonville, FL. Residencies include Pop-in Residency at Artspace, Raleigh, NC, Hambidge Center, Rabun Gap, GA and Vermont Studio Center. Schoon earned an MFA in Photography from Ohio University in 2009. His photographs are included in the permanent collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, CA, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, and the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. He has been awarded residencies at AIR Serenbe, Serenbe GA and the Camera Club of New York, NY.

They currently have work on display in All Terrain at the Spartanburg Museum of Art, and an upcoming exhibition, Verisimilitude, at Buckham Gallery.

McGuire and Schoon each serve as Associate Professors at the University of West Georgia.

The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial

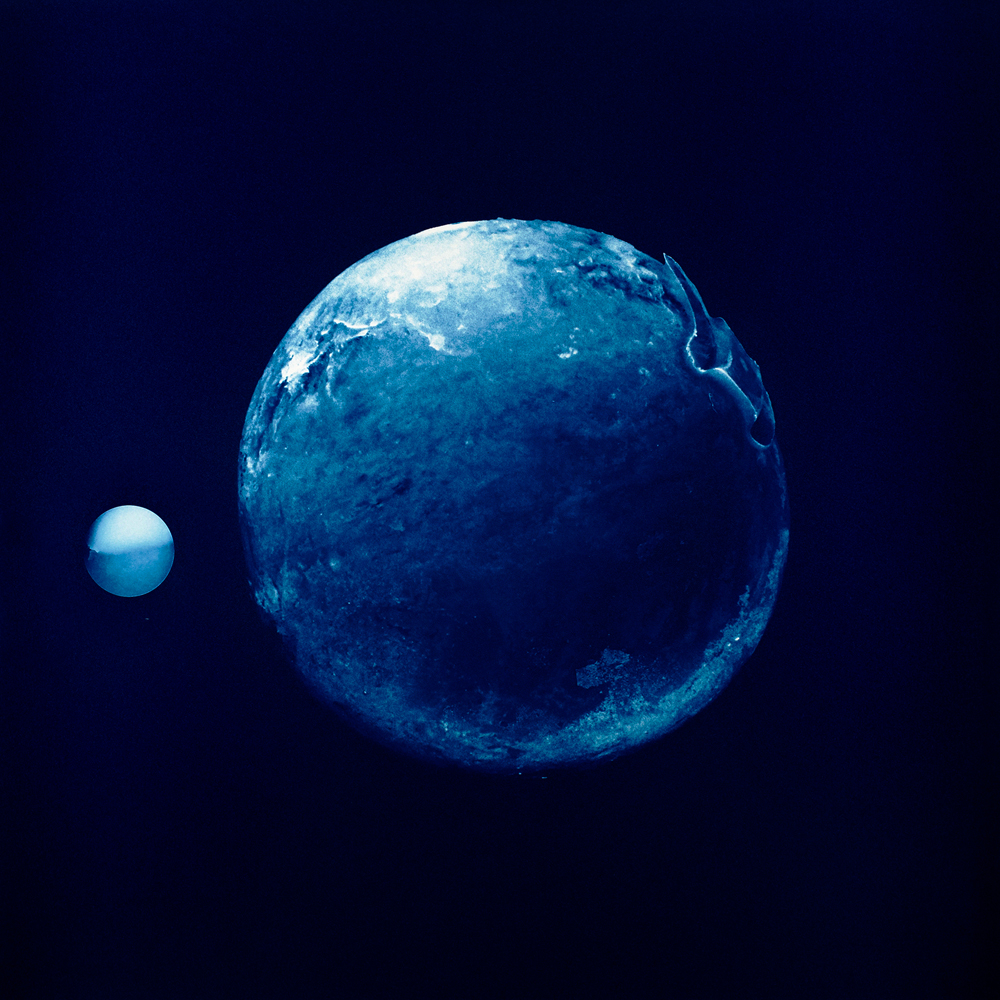

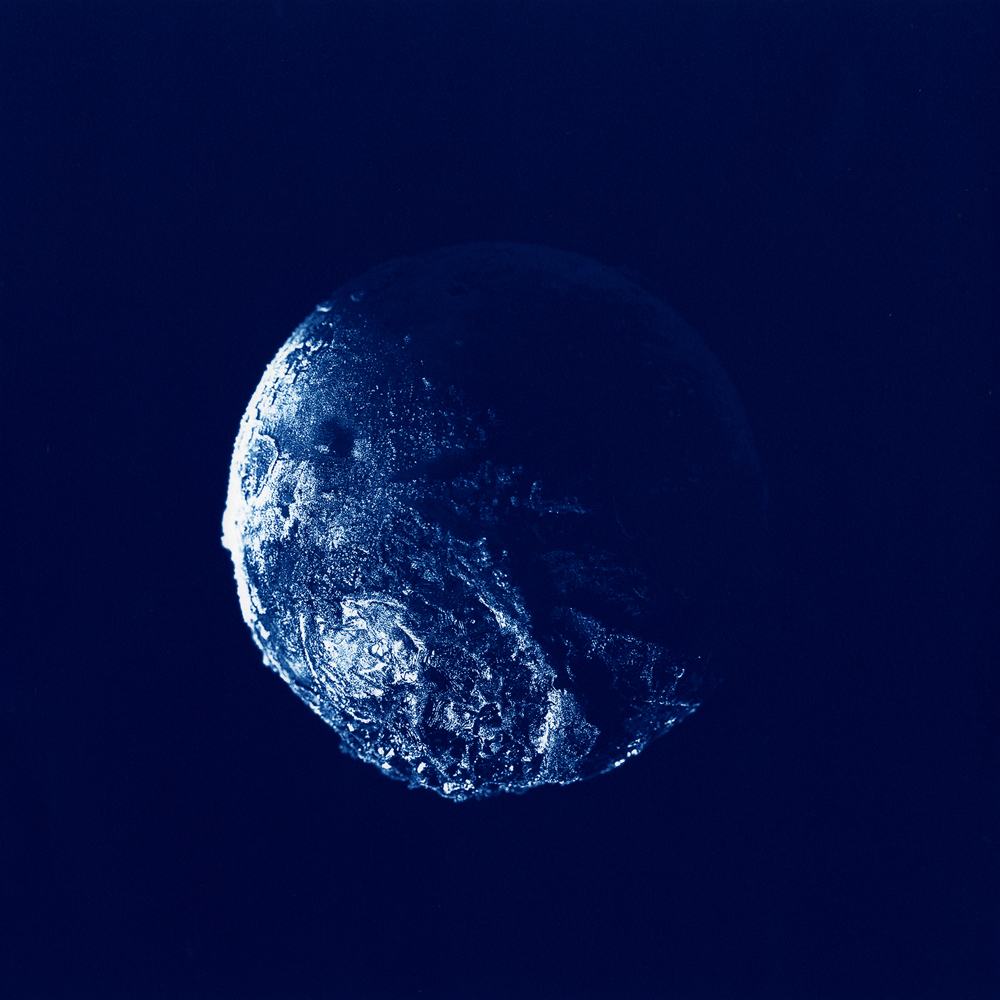

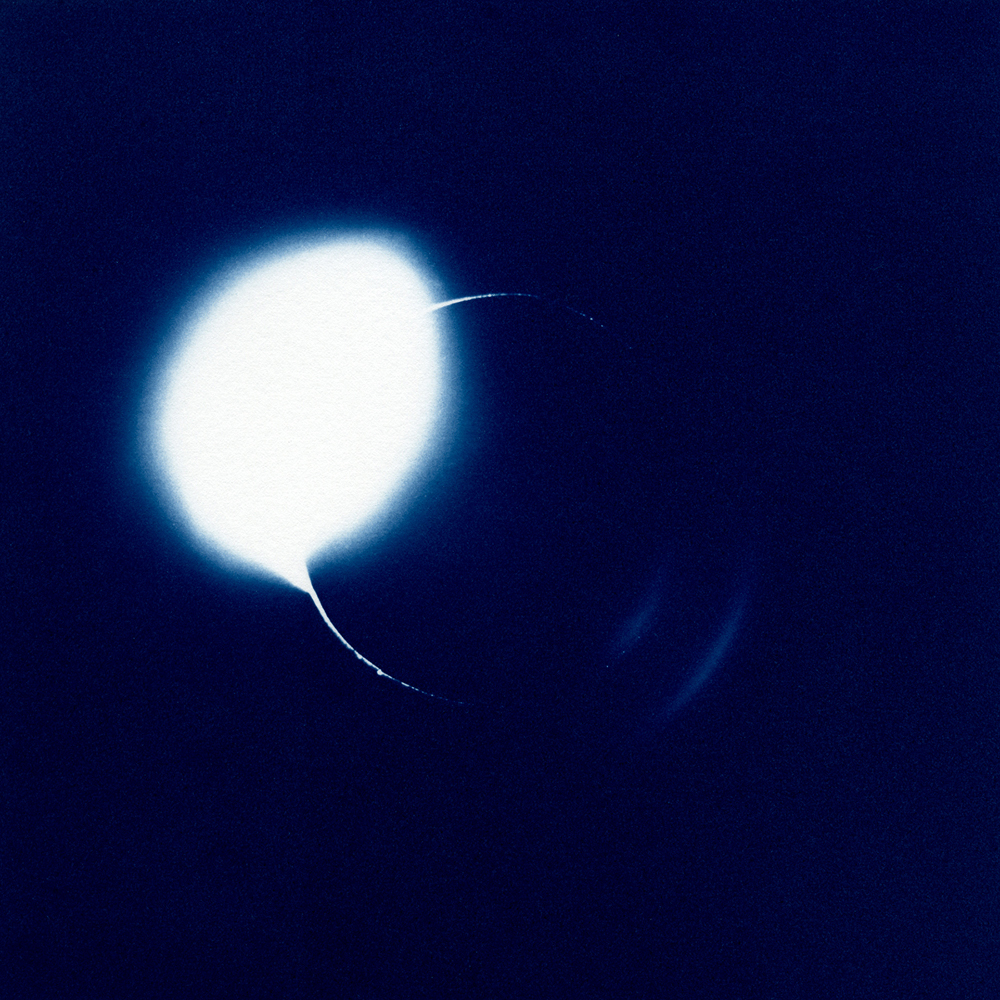

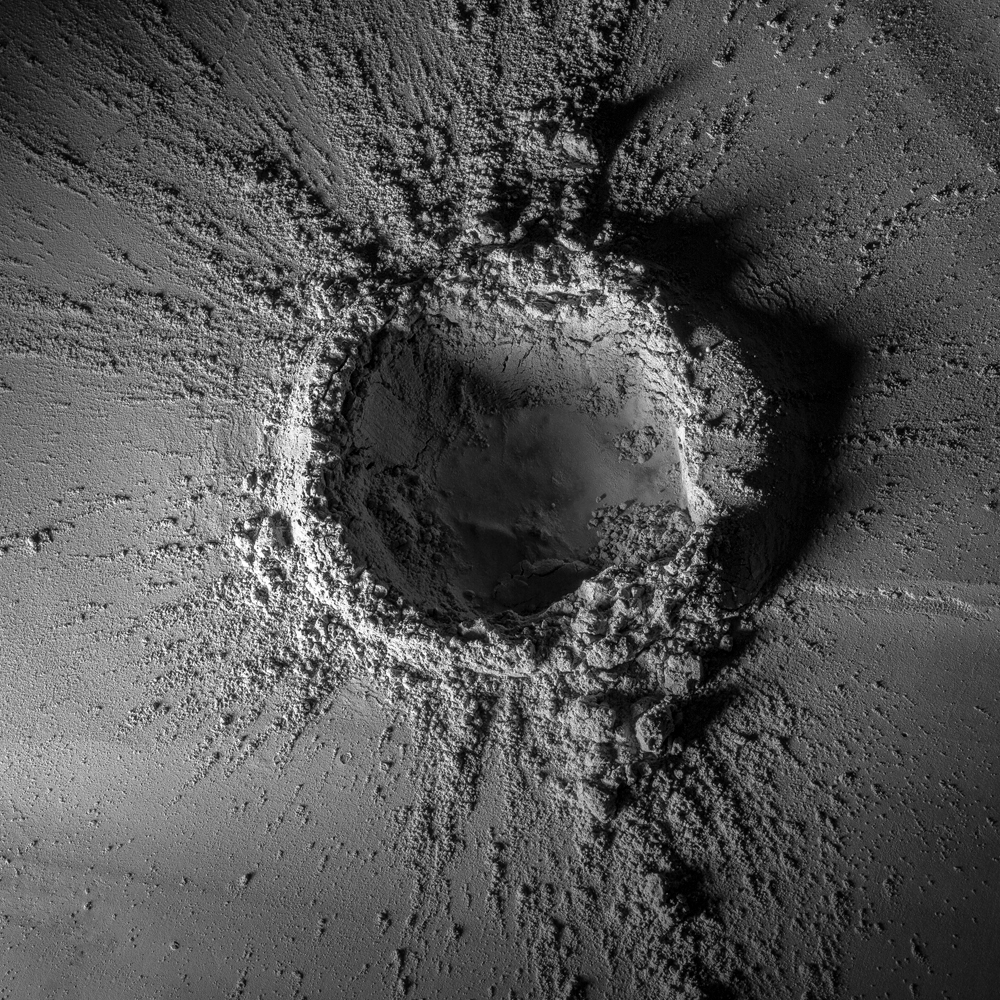

The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial merges science and art by exploring the complicated relationships between observation, representation, and understanding. This collaboration springs out of our individual research that addresses different aspects of the real, the artificial, and unattainable.

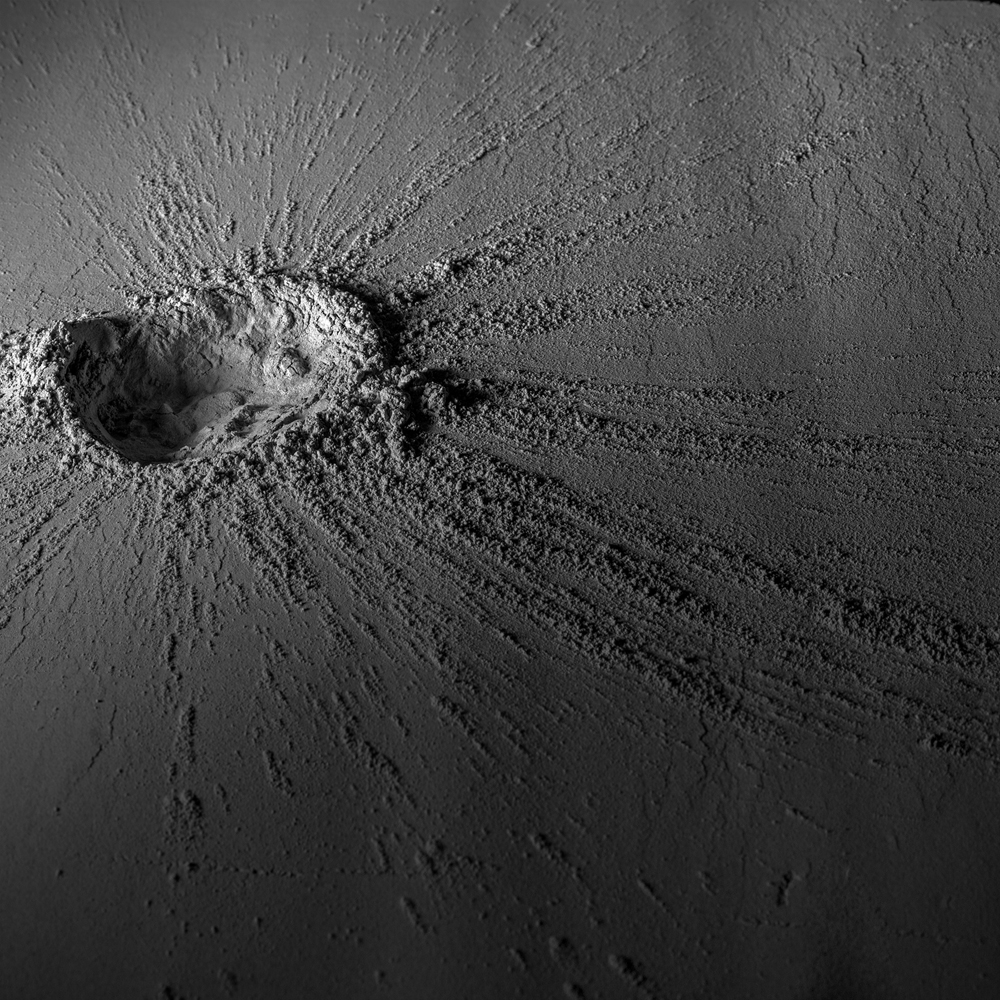

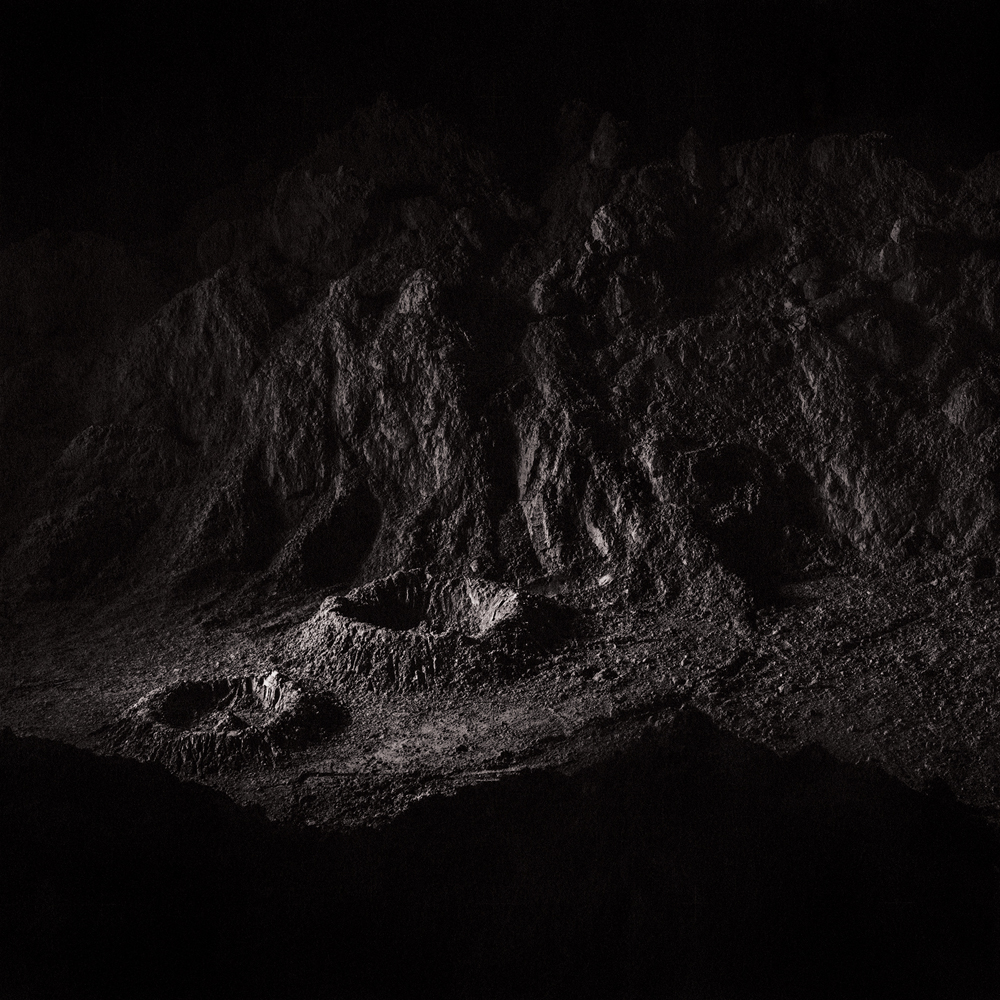

Our images focus on early astronomical photographic attempts at rendering visible, yet unattainable objects on the moon’s surface. The quest to see these unattainable objects became a popular obsession after fantastical images depicting the moon were published with a series of articles in the New York Sun in 1835. These articles later known as “The Great Moon Hoax” along with Sir John Herschel’s photographic model: “Lunar Copernicus Crater” of 1842 and James Nasmyth’s illustrative book: “The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite” of 1847 all helped to expanded scientific curiosity beyond the limits of human vision and the possibilities of the scientific photograph. These images, despite their reliance upon drawings or models for representation, played upon the popular belief that photographs have an undeniable authenticity and are representative of the “the real”.

The images depicted in The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial were realized through the creation of three-dimensional sculptures for the purposes of making photographic prints. At times referencing lunar models, Apollo era images, and telescopic astrophotography, this body of work bridges a gap between historic and modern modes of scientific representation while re-contextualizing and bringing them into a contemporary vernacular. The images of the sculptures are presented using historic photographic processes such as salt prints and cyanotypes as well as more contemporary silver gelatin and inkjet prints. The transformation of sculpture to prints provides a contextualization of photography’s ability to render convincing, useful, yet misleading scientific imagery. In their presentation, the images encourage the viewer to take a closer look at science, the imagery that represents it, and how it impacts popular understanding.

Daniel George: What components of your individual research did you bring to the project? And how did it inform the final outcome?

Mark Schoon: At the time this project began I had been thinking a lot about distance as it relates to outer space. Specifically, the concept of infinity and the idea of a multiverse. It relates back to previous photographs I made about the home as well as a series of landscapes titled “Center Space”. Each of these projects led to spending some time thinking about space, place, distance, and perception.

Casey McGuire: Mark and I had both been creating works conceptually tied to home and place. I was looking at recreations that pertain to concepts of “the Real.” Initially I created a sculpture of Herschel’s “Sculpture of the Capricious” crater. This led to more in-depth investigations on my part and I became intrigued in Nasmyth’s book, The Moon: Considered as a planet, a world, and a satellite. His attempts at creating landscapes and scientific imagery aligned with my interests in recreations and perceptions of “the Real.” I was motivated by the question, How do you show and explain something that we can’t touch or see? This book and other historic images like it were the launch pad for many of the early series of images we made.

DG: Tell me more about your interest in using the medium to address aspects of the unattainable—and the significance of creating evidence of something, perhaps, unachievable.

CM: Photography is a medium that grew out of scientific desires to document what early astronomers were seeing through their telescopes. But these early telescopes had polished lead lenses. This fact is so captivating to me. Maybe we will make a telescope with a lead lens to show the unachievability of an image from these early telescopes. Contemporary technology may be more complex, but the images that are made with it are no less problematic. Even today, images of space rely on our perception of what an image provides us with. We have to believe in the image, we have to think that science is true, so this image must be true. This is a slippery relationship. Who is viewing the image and who made the image are significant factors. These are two points that led to the use of photography as our medium of choice.

MS: Like Casey said, History has also been a strong guide in the shaping of this work. Thinking back to some of the earliest photographs of space in the 1840s, primarily of the moon, we see the detailed renderings of a distant object that no one but a select few people had ever observed beyond the power of the naked eye. By this I mean that the photograph now presented people with a level of detail that could only have ever been seen by someone fortunate enough to have a telescope. Photography simultaneously bridged the gap and exacerbated it. The question of access and expertise was and continues to be a problem with scientific imagery. Who has the tools to make the image and the knowledge to understand what they are looking at? Some contemporary examples are the images from the Hubble Space Telescope or Voyager’s images of Uranus or the famous “Pale Blue Dot” or any of the Mars Rover images. We see these places or objects in a way that feels close and looks understandable but in reality are places we will never go and are millions of miles away or even thousands of light years away, in the case of the Hubble images. It is interesting to note how important the captioning of Nasa’s images are to understanding what you are looking at. The words are often far more significant to the layperson than the image, contrary to what we might believe our experience is.

CM: The Hubble is a great example. They are colorized for the viewer to understand and comprehend the gases and particles in the image. When I learned that it was not what space actually looked like, I was completely confused. I had believed the image.

MS: All that said, we seem to reserve this dream or hope to make it possible. It’s the reason science fiction is valuable to science. It gives us the permission to dream about things that are impossible or unattainable, dreams that will guide our future missions, because of a desire for that which has previously been unattainable or unachievable. It’s the reason we are still hopeful for an encounter with life from another solar system even though the next nearest star is 4 light years away.

DG: Your work highlights the illusory nature of photographs, while alluding to factual, scientific documentation. What are your thoughts on straddling/blurring the line of accuracy and fiction—particularly when it, like Nasmyth’s illustrations, expands an individual’s scientific curiosity?

MS: I take great delight in the blurring of the lines in the process of making art. It is a desire to work in the space where so many of us have found truth when we didn’t know we were looking for it. It is the space that artists occupy so well and that traditional beacons of accuracy and fact, like science, struggle to inhabit.

CM: It’s a balancing act between play and research when we make images. I think the delight Mark talks about is a driving force in this work for both of us. Nasmyth’s illustrations support both the factual and fictional aspects of our image-making process.

MS: The play and fun that Casey brings up is key. Oftentimes we start a day with an idea of an image we want to make but let the studio process guide us. We’ve found a need to remain open to what the process of making can offer while being observant of how the images we created fall into the “Scientific Imagery Lexicon” or not. This seems to be most successful when the new images exploit our societal expectations for what an image of space should look like. It’s a slow process of co-opting the visual vocabulary that photography and science have etched out over the last 180 years.

DG: We are viewing these images digitally, but your artist statement describes your intentions to create various types of prints as a means of transforming your sculptures into something more convincing. Why do you suppose a physical print still has the ability to mislead? And why is it important that we suspend belief when viewing your work—even for a moment?

CM: Our use of historic image making processes speaks to our interest in the unattainable. We feel that our approach to creating “the perfect” image through the use of cyanotype and salted paper printing processes supports our questioning of the image as a document. I think each time you encounter an image, there is a small and specific key moment when you realize that it is not a “real” document. These moments are sometimes more obvious than others. The intimacy of the 16×16” print and the depth of the materials help these objects take on a history or life that they do not have otherwise. We are really fascinated by the imagery, but also by the intimacy of an image.

MS: There is something about a physical print, especially a matte surface print, that feels comforting. Even in a frame, under glass, the tactile nature of the print comes through. It is like a double illusion that the screen or projection has difficulty pulling off. The double illusion being that of the object represented and the tactile-like sensation of the framed print.

DG: Obviously, this project was created prior to the current pandemic—where there is an unfortunate, popular movement characterized by distrust of scientific authority. Since your work disputes the veracity/authenticity of a medium that some consider to be a visual authority (though, that notion is unquestionably problematic), have you been thinking about these themes further? Have your perceptions of the work changed in light of current circumstances?

MS: Making this work and having lived with it for a while has shown me how exhausting it is if you really want to be critical of all the images you encounter. It can get discouraging to think about how misaligned our hopes and expectations are for photography to act as a witness or be a record of fact.

CM: It has been a topic on our radar. We continue to look at NASA’s images and artistic renditions. It is a confusing time and we do get asked a lot about our take on the current political climate. But it is important to us to acknowledge that these are issues that have been happening in science and photography for a long time. That history is what drives our questions, and like Mark said, that questioning can get discouraging.

MS: To continue on Casey’s thought about the persistence of this issue, it has always bothered me how photography gets dragged into arguments to prove or disprove something. It’s much the same way politicians or pundits handle statistics or how they decontextualize quotes. The image is an image, is an image, is an image, period, and we must acknowledge that before we can move in any direction. It’s not THE TRUTH, it’s not definitive. It is a tool, a reference, a guide, an illustration, an illusion. While I know this sentiment feels elementary, even annoying to most, I believe our judgement generally still suffers from the seduction of the photographic image.

CM: To that, I think we want our images to be seductive, to pull you in and make you question these images and their authority. With all of the media we are encountering, we will see how it affects our work as we move forward. For now we are mostly talking about how weird everything is around us.

MS: In our work I hope that it can function on at least 2 levels:

- To be pure image and a wholly new experience for the viewer.

- As an object that gets viewers thinking about what they are looking at and start questioning their own understanding and acceptance of the scientific image.

To make one thing clear, the idea of questioning science is inherent in the scientific process and I hope that our work falls along those lines. Somehow today, in popular culture at least, we want to accept ideologically driven conspiracy theories as valid ways to question science rather than the genuine quest for knowledge and understanding. It is antithetical to a shared goal of most science and art: to better understand who we are and how we fit in the universe.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Patricia Howard: Unknown AncestorsFebruary 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025