Akea Brionne Brown in Conversation with Colette Veasey-Cullors

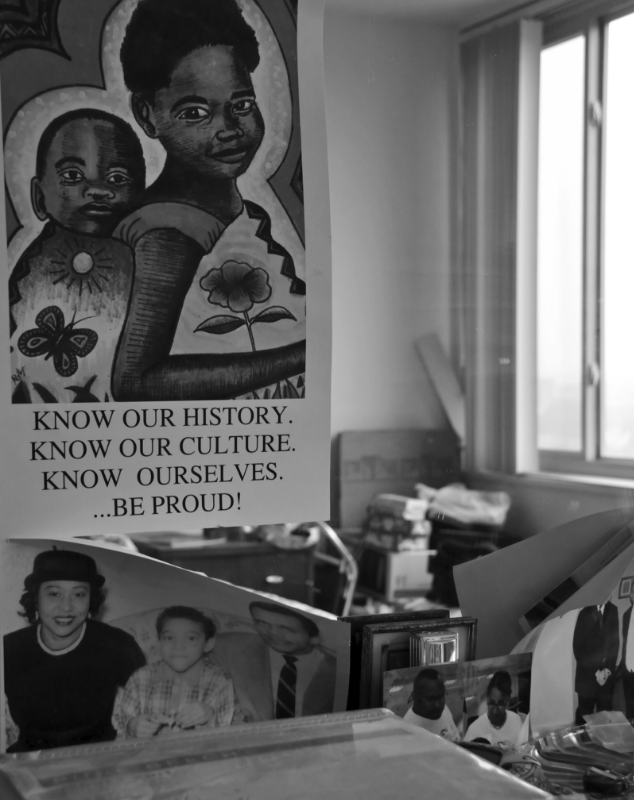

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Contradicting Beauties

I met Colette Veasey-Cullors during my sophomore year of undergrad, while studying Photography at MICA. She was one of only 2 professors of color I had in my entire collegiate career. She quickly became a mentor and is someone I hold dear to my heart. Her wisdom, honesty, drive, and constant dedication to the community is one that deeply inspires me. There were many times I wanted to quit pursuing photography, but Colette’s presence and role in my education (despite only taking 2 classes with her) is a large reason why I decided to continue to pursue a career in photography. Her work beautifully captures the small moments within black families, motherhood, and the beautiful (and often overlooked) experience of moving through the many stages of life as a black woman. She does it so beautifully, so with deep admiration and respect, I wanted to use this space to highlight her narrative, if only for a moment.

Akea Brionne is a photographer, writer, curator, and researcher whose personal work investigates the implications of historical racial and social structures in relation to the development of contemporary black life and identity within America. With a particular focus on the ways in which history influences the contemporary cultural milieu of the American black middle class, she explores current political and social themes, as they relate to historical forms of oppression, discrimination, and segregation in American history.

Akea Brionne has received the Visual Task Force Award from the National Association of Black Journalists. Her work is also featured in the Smithsonian’s Ralph Rinzler Collection and Archives, and was recently acquired by the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art Collection. She was announced the 2018 Winner for Duke University’s Center for Documentary Arts Collection Award, as the 2018 Documentarian of Color. Her series, Black Picket Fences, was acquired for their permanent collection, and is on preserve at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. She was nominated for PDN’s 30 (Photo District News) 2018: New and Emerging Photographers to Watch. Brown was recently named the 2019 Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize Winner, juried by Laylah Ali, William Powhida, and Regina Basha.

Akea received her BFA (2018) from the Maryland Institute College of Art, in the dual degree program of Photography and Humanities. She is originally from New Orleans, Louisiana and is currently based in Baltimore, Maryland.

Colette Veasey-Cullors is an artist and photographer whose artwork throughout her career has continually investigated themes pertaining to socio-economics, race, class, education and identity. She seeks to question our personal connections to these subjects and how one might justify and rationalize their existence to themselves and others.

Colette has exhibited her artwork throughout the United States, including The California African American Museum in Los Angeles, The African American Museum in Philadelphia, The Museum of Fine Arts Houston/Glassell School of Art, and The Chattanooga African American Museum. Her work is included in the publication MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Adama Delphine Fawundu, BLACK: A Celebration of a Culture by Deborah Willis, Ph.D. and she produced the cover design for the textbook African-American Sociopolitical Philosophy: Imagining Black Communities by Richard A. Jones, Ph.D.

Colette’s collaborative interest resides in the process of social and creative engagement with individuals and communities, with a particular interest in underinvested and underrepresented communities.

Colette is currently Associate Dean for the Division of Design and Media at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). In 2012, she was awarded the Maryland Institute College of Art, Board of Trustee Excellence in Teaching Award.

Colette received her MFA in Photography from Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in 1996 and her BFA in Photography from the University of Houston in 1992.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Tillie

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Tillie and George Eating

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Dresser and Mirror

Akea: The second class I took with you was “Socially Engaged Documentary Photography.” You placed a lot of emphasis on NOT allowing the class to just be photos of abandoned homes in Baltimore, and pushed a lot of us to actually engage with the people of Baltimore. So with that in mind, I’m curious to know how you feel about the role of photography with the recent protests that have been consuming much of the nation in the past few weeks?

Colette: I’ve thought for a long time that photography is at the center of political social discourse right now. I feel like “the image” has so much power and weight and has forged alongside the Black Lives movement itself. I mean, there are already iconic images, right? Devin Allen is a great example of that. And I think that image has stuck with our minds and has helped to frame political movements right now. I also think about the Hank Willis Thomas Four Freedoms movement that’s happening right now and that billboard campaign, which is all about centering and placing imagery, whether it be photographs or statements of some sort. But mostly some form of photographic imagery within key strategic places to actually visually make statements. I think our society is really built around imagery. I mean, from commercial to social commentary to political, people don’t think about it (image making) necessarily as socially engaged or politically engaged or documentary or even artistic, right? I think they just accept it as being a part of society today.

Those of us that are image makers, we understand the complexities around how to make an image, how to create an image, the narratives that go along with that, the communication that goes along with that.

It’s different than just “snap”. And you’ve got something substantial that carries particular weight. But how you frame that, the perspective, how it’s read, you know, those of us that are in the actual discourse, that are learning subjectively what it means to curate and create an image, that’s different than snapping a picture.

But I really think that the photographic image is so embedded in society that there’s no way of separating it from how we actually live. And I think the layperson who isn’t within art or even journalism, I would say, doesn’t really think about it, right? They just accept it as being. You can think of anything commercial and there’s always some form of a visual attached to that, so you can’t even separate it. I think right now, black photographers are really at the center of the political and social discourse that is happening right now, and I don’t separate it from the movements that are happening.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Her Floor

A: Do you think that will continue?

C: Does anybody know the answer to that? Oh, that’s actually equable. You know, everybody keeps talking about Black Lives Matter right now and everybody is like “I’m down with the cause and I want to help and I’m an advocate and I’ve got your back” and blah, blah, blah. And everybody keeps asking, why now? Why now, why now? Why now? What’s different about this particular moment in time? And some people have said, oh, it’s because of social media, it’s because we saw it on there. Or it’s eight minutes and 40 something odd seconds. And I do think it is the time of that (referencing the video of the killing of George Floyd) and the horrific nature and how long; thinking in terms of time as being something tangible. But then again, back in the 90s, you know, Rodney King was the first one to actually be recorded in that particular way about police brutality. And it was, what, 12, 13 officers beating him, right? And we have that record, we have that visual. So I’ve been asking what’s different, you know? What is different? And everything in between from 92 to now, right? There has been a visual record of that.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Her Stove

A: So do things feel different to you now? Do you feel like people are truly ready and willing to sit with themselves? Primarily white individuals and non-black POC (People of Color), who can often fall under the guise of not really needing to “do the work.” So do you think they are ready to really center and uplift black narratives?

C: I do think that’s that’s the marker. Is society ready for that? Because that’s a major shift that is not temporary. I think with that, there becomes a particular personal cost to white society. That is the question: are they really ready for true, actual change? I will say your generation that is forging that question and has the actual platform, and should have the platform, to be perfectly honest. What I love about the movement today is that the leadership is not just asking for change, but demanding that change through a structural shift, which is the difference.

It’s not enough to just say, open the door. Your generation is saying, fuck it, we’re tearing that freaking door down and we’re busting through and we’re rightfully taking our seat. Will it last beyond just this particular moment once the dust settles? I don’t know. I hope so. I feel more hopeful than I ever have, and I don’t know if it’s if it’s because we have so many things that have come to head right now, but it very much feels like a global reckoning.

This issue is a pandemic, a global pandemic. You have 20-somethings that are at the political front saying, “this is not the society we want.” You have a US leadership that has brought race to the center of the discussion; race, misogyny, you name it. I do feel like society right now has to take a particular side, and I think that’s what’s happening right now – all of these dynamics that have come to a head simultaneously. To me personally it feels like as a country, we have to make a decision right now. And I feel like our democracy is really kind of on the line. I mean, it very much feels that way. In my 53 years, I have never felt that – truly.

From where I sit as an administrator in an art and design institution, there’s a reckoning there that’s happening simultaneously too. I love that students are really demanding that they have a say in their education. The student population has before toyed with that a little bit and made some demands, but this feels- again- very, very different because it’s not letting up. They’re saying, you know what, we’re going to go outside of what historically has been the cultural norms of how you demand change, we’re going to supersede that, we’re writing a new playbook right now and it’s going to be on our terms.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Anguish Present

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Anguish Future

A: With that in mind, as a photographer, what feels different to YOU about right now? And specifically in relation to your long career in photography and education, and how long it’s taken you to get to the position you currently hold. Even as young black creatives, while we are still up against a lot, we don’t have to pass through many of the hoops that you and many others had to go through before us. So how do you feel about all of that as a maker?

C: I think you know me well enough to know that I don’t separate my careers. But I think of everything that I do as part of my practice; so I’m going to answer that not just as a maker, but as a mentor, as a community educator, because all of that has framed every single decision that I have made since I started on this path. So, yeah, it was it was not a direct route, but I will say what has always led me along that path has been having mentors. Creativity has always been a part of who I am. I didn’t necessarily know that it would be photographic in nature or that direction would be photography or image making or anything like that. But I always knew it would be something with creativity. And so photography, I felt like I kind of came to it a little bit late, to be honest with you, because I was already in college and had been in college for a couple of years.

I’m a first-generation college student and so my path was kind of all over the place trying to figure out my education because I didn’t really know how to do that. I didn’t have the financial resources for college. So I started with community college first, then a small university and then a larger university. It was at that third institution that I really kind of found photography and found mentors to help me along the way. It was simultaneously while in undergrad school that I actually started teaching again through mentors who saw something in me and led me. So I was building both practices somewhat simultaneously. I understood the power of mentorship and having people kind of help shape a path and help you understand the dynamics of thinking about yourself, your career, helping to answer questions, helping to kind of shape your thinking, thinking about professionalism, thinking about growing up, thinking about all of these things simultaneously, because my parents weren’t able to help me with any of those things. They kind of were hands-off and had no clue of what I was doing at any step of the way and didn’t really ask; just on the sidelines. So there wasn’t a rule book. I was figuring it out and being open to possibilities.

Doors would appear and I had to be open to those doors, saying OK, I’ve never done this before. I don’t know how to do this, but hey, let’s try it. I was also always invested in community because I was teaching at a high school. Working with those high school students, again, the importance of mentoring young kids within the community through creative entities, building things that didn’t exist, working with the Collective for Black Women- it was all this wonderful mix. And I never said no to anything. I never thought in terms of, oh, a career or a practice is just making art. Because early on, at 21, I was doing all of these things together and was passionate about all of them. I didn’t let one take precedence over the other. Today, even when I speak to groups about pedagogy, I openly talk about how you get to define that. You get to decide what your pedagogy looks like. Nobody else defines that for you, and there is no one right way.

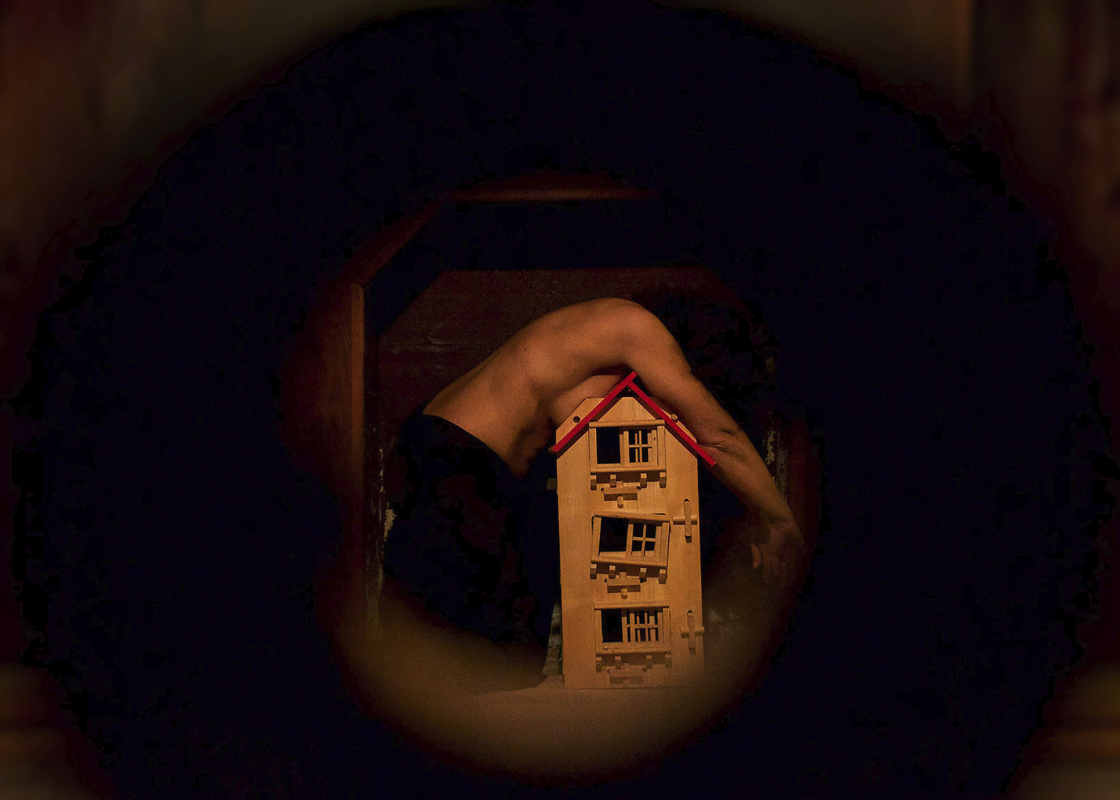

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Cover

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Confine

I initially thought as an image maker I should be looking externally. I thought in order to be an “artist” you have to show in galleries, you have to show in museums. You know, you’re looked down upon if you are just an educator. I had never thought, oh, I’m going to go into education. I never, ever made that decision. Doors just kept opening within education and people kept saying, oh, my God, you’re really good at this. I really loved working with students. So I was twenty four, I think, when I started teaching at the High School for the Performing of Visual Arts in Houston. And I loved it. Then I decided, you know what, I really do want an MFA. So as I moved in to do my studies for my MFA, some of my high school students actually came along and were accepted to do their BFA at the same time that I was doing my MFA at MICA.

And so again, here come my students. We’re going to school together. So of course my natural instinct was, these are my kids. I’m going to continue to mentor them. At some point I realized, you know what I’m really not interested in putting all of my eggs in one basket. I still want to make work because I still feel that need and necessity to express myself in that way. I still like showing. But it’s not super important, it never really has been. I realized that although I love being inside the classroom, I could only affect change to a certain degree inside one program. So I started to work outside of that by building initiatives and doing bigger things, which, you know, some people were like -Colette, you’re out of your lane. I realized that if I really wanted to open up doors and really, really start to affect change for students and staff and faculty that look like me, that I had to do something a little bit broader than be in one department.

I started to move into the administrative space, which comes at a cost because I’m can’t be in the classroom. I have to say that really hurts a little bit, you know? My last class just graduated. So it’s even more profound for me right now because I know that from this point forward all of the students who are at my institution will never have me as a as a teacher. What I really want to do is be able to be an advocate in a position to really change the narrative. And that has to do with curricula, that has to do with initiatives, that has to do with community-based work, that has to do with speakers, that has to do with acts. Because without a connection to all of those things, you are in some form of isolation and can only affect change in a limited capacity.

Beyond just my one particular institution, I’m also very interested in connections on a broader, more national level and so I’m working towards that too. But that also means a seat at the table. That also means having the opportunity to be in positions where you are truly able to effect serious change. I feel like that’s the place I have been in for a few years now, really holding people accountable and being a little bit loud and sometimes that’s uncomfortable for me. I’ve been in a lot of uncomfortable positions. My husband and I have had multiple conversations where I’ve had to say, you know, I’m putting myself on the line, I might come home and not have a job today, but I have to be true to myself. And that’s just part of being in an educational institution. It’s one of the things that the student population doesn’t see. But I also understand from a student perspective, because I’ve been there, you know what I mean? I’ve been one of the few and I know what that feels like.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Milk Rings

A: How are you making work nowadays? Like what what does that space and that time look like for you?

C: I am making work, I’m actually working on two projects right now that are extremely different. One is very much a documentary project, which is very close to my heart right now. That one is just moving along on its own. Ultimately I’m thinking it probably will be made visible some time down the road. Right now, I don’t feel a need or a desire to show any of that because I’m just immersed in the documentation of it and it’s slow and it’s moving at its own speed. It is what it is right now. It just has its own life because it has to and it needs to have its own life. When it’s finished, it will be finished.

There is another project, parts of which have beens shown. One component of it is actually in a show in New York. But because of physical distancing, the show has been up way longer than it was supposed to be.

And the other piece is still kind of growing. It actually is about me, but not just about me. It’s a commentary kind of on the state of where we are as a society right now with race and race relations.

A: Could you describe what your process is when you’re in the space of “making” work?

C: Oh, my process! My process is slow, but it’s because I’m not prioritizing shows or anything like that, I’m just making and creating the work. But I am one that tends to work simultaneously on initiatives and creative projects all at the same time. Because I’m not working towards any particular shows right now, I’m just making when I feel the need to make, which is very different. I mean, I’m amped up if a show comes along, like the show in New York (at Walencora), and I start to say “no” to other opportunities on the side, which has helped me create a stronger work ethic.

Right now, I’m kind of in the midst of speaking at different things. I’m prioritizing creating initiatives and engagements for other people to speak. Although, simultaneously, I’m also in the midst of a project right now that I’ve got to finish.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Room With a View

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Hands

A: So what are you shooting with? Are you still shooting with film?

C: It’s all digital. I just bought a new Nikon D700. But I’ve been shooting digital for a while. You know how some people are just really all about the medium itself? I’m less of that person. I am not a die hard photographer and I never have been. I love the medium, but I think that’s why I also wear multiple hats, because for me, it’s about broadening this creative experience, right? I’m not a traditionalist. Photography is not the end all be all for me. I am very much am rooted in images, but I feel that that can be expressed in multiple different ways. And I’m interested in bringing so many other voices to the table and expressions in multiple ways, but still rooted and connected to the photographic image.

A: Yeah, I deeply resonate with that. That’s how I’ve been navigating!

C: Yes, I know, I very much see our connections and, I don’t know… I think that’s why I’m so connected to you.

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Portrait with a Bow

© Colette Veasey-Cullors, Contradicting Beauties 4

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Brandon Tauszik: Fifteen VaultsMarch 3rd, 2024