John Willis: Mni Wiconi: Water is Life; Honoring the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and Everywhere in the Ongoing Struggle for Indigenous Sovereignty

Renowned photographer John Willis, a nationally and internationally exhibited artist with work in over sixty museum collections and author of three other photography books, has just published Mni Wiconi: Water is Life. It is the recipient of the 2019 Gold Medal for best regional book from Foreword Indies. Willis has received numerous grants for his work and was given the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Photography in 2011. His teaching experience includes Marlboro College––where he is still an emeritus professor––Princeton, Rhode Island School of Design, and Harvard University among others. What makes him perhaps most qualified to have documented Standing Rock, besides his extraordinary photographic skills, is his work with the Lakota people over the past three decades. A co-founder of the Exposures Cross Cultural Youth Arts Program, he has been taking students from across the country to the Pine Ridge Reservation since 2003 and has also taken youth from Pine Ridge to places like Vermont and New York City. The aim of the program is to bridge cultures and increase understanding of indigenous people, as well as to inspire those on the reservation to find their own voices and tell their own stories. The struggle for indigenous sovereignty has been ongoing since this country was formed and John’s mission has been to help overcome injustice and to create a more accurate narrative.

I am deeply honored to be reviewing this important book, which is particularly meaningful to me, having spent a week at Standing Rock. After being with the Lakota people so many times on extended trips over the years, John was left believing the only way to properly offer a narrative of the movement was to include over 50 people’s contributions, most of whom were indigenous, in addition to his own photographs and writings. A layered assemblage of contemporary and historic photos, stories, poems, quotes, and text that took Willis two years to compile, the book is both highly educational and humanizes the struggle in a poignant and powerful way.

Though the book tells a much more complete story than was portrayed by the media, Willis concedes it could never be comprehensive enough to document all the events and stories leading up to, during, and after the movement. Nevertheless, it puts Standing Rock in historical context and also provides a timeline for what happened. Willis made six trips to North Dakota between September 2016 and December 2017 and spent a total of eight weeks living out of a car at the Oceti Sakowin Camp. When he first arrived there were about 500-700 supporters. On later trips he saw the number ebb and flow to between 12,000-15,000. Representatives from 240-300 native tribes joined the protest, as well as many thousands of people from around the world. The experience was life changing for most. In the foreword, Terry Tempest Williams quotes David Archamault II, the Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, who asked for prayers of petition for his people and all who stood with them. She says prayers invite us to reflect on what is in our hearts and that what was called for there and is still being called for at Bears Ears “is an intercession of voices on behalf of the land, on behalf of people in place.”

The North Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) was originally supposed to be routed near Bismark, a city with a population that is 92 percent white. The citizens there complained that it was too close to their water supply, so it was relocated to pass beneath the Missouri River just above the Standing Rock Reservation’s northern border. As is almost always the case, this environmental issue is a human rights issue, and indigenous people were having their land threatened by outside forces once again. Yet, DAPL not only threatened the tribe’s water supply and sacred sites, which should have been egregious enough, it also threatened millions of people living downstream. Though indigenous people led the movement, they recognized that the cause is for all people. As John states in his introduction, “The call from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to resist the Dakota Access Pipeline was a call for humanity to recognize that our natural world is not an endless resource to be stripped without consequences for our actions. We must prioritize finding ways to live in harmony for the benefit of all, including the generations yet to come.”

John’s work will be on exhibition at Gallery Kayafas in Boston, opening September 4th and running through October, 2020. The main room of the gallery will present Requiem for the Innocent, El Paso and Beyond, a collaboration with the writer Robin Behn and Composer Matan Rubinstein. In the smaller gallery John will share images from Mni Wiconi, Honoring the Water Protectors.

©John Willis, Movement from Oceti Sokowin Camp to the North Camp along ND 1806 (a section of the Lewis and Clark Trail)

The book, which is dedicated to all Water Protectors throughout the world, opens with a masterfully lit scene with dark shadows in the foreground and people traveling in a caravan with some on horseback in the middle ground. The people are so far away that their features and dress are not discernable. This timeless image resembles a painting as much as a photograph and could easily be of a migration at Little Big Horn over a century ago, which was the last time so many tribes congregated. The Missouri River snakes through the landscape in the distance, a reminder of what is at stake.

The next image in the book is of Sunni wrapped in a blanket in a snow-covered landscape. Though the blanket is keeping the person warm, it is also a visual reminder of the possible transmission of smallpox via blankets, though this controversial theory is not explicitly referred to. These first two images set the historical and cultural context for the movement and remind us that recurring systemic practices led to the protests, as John notes in his introduction.

©John Willis, Lakota Tobacco Prayer Ties along the Cannonball River in the Morning Mist (Each tie is made with a personal prayer offering)

This image accompanying the dedication page conveys the importance of personal prayer. The mist also connotes invisibility. Echo Hawk, a consultant for the Reclaiming Native Truth project, believes that “Invisibility and erasure is the modern form of racism against Native people.” Astonishingly, in a 2018 poll John refers to, forty percent of Americans believe that Native American’s don’t exist.

What is striking about this foreboding photograph is the water protector’s cap, which says “Make America Indigenous Again.” Though Trump was not yet in office, it is a twist on his campaign slogan and perhaps also implies it never was great.

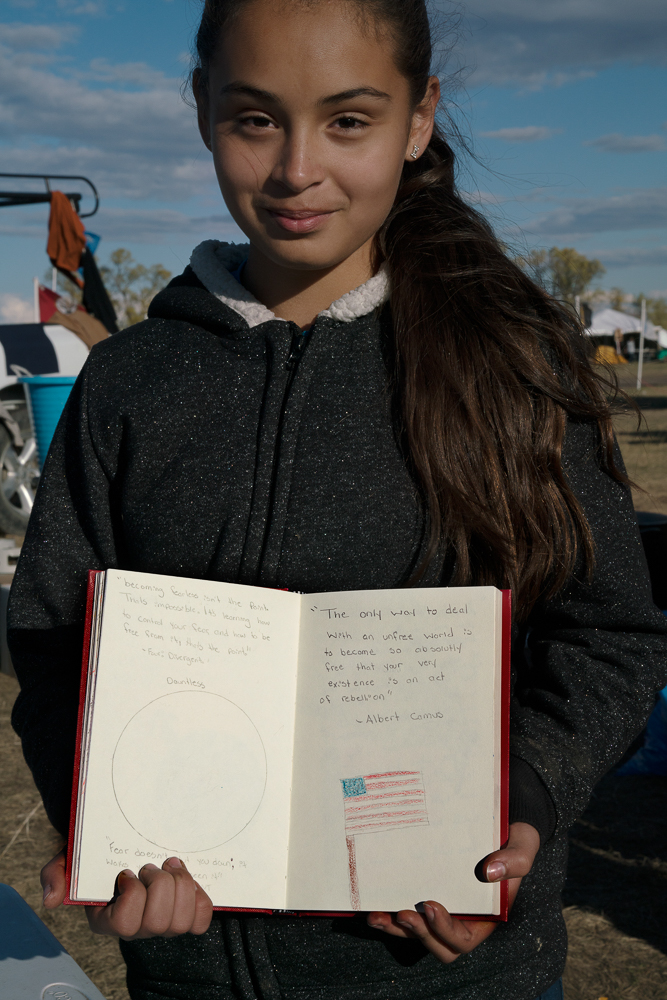

The photograph of the tipis in the mist is part of a group of images that accompanies a narrative by Cait Mazzarella, a college student of John’s who worked in the school. She tells of a huge windstorm coming through and blowing down all the tipis, so they gathered in the big tent and read a story. She describes the rapt attention of the students and what her experiences at camp taught her, namely “to respect our Earth and each other and find intimate community in times of oppression and defeat…” According to Christopher Lamb, another college student, what makes a river is not how it flows through the landscape “but rather its power to gather around itself the myriad relationships that together comprise it, the way in which it fosters a sense of reciprocity between beings.” It is this belief that one must return benefits for benefits received that is the foundation of sustainability and what makes the land and anything on it sacred. What struck me about Willis’ photographs and my time at Standing Rock was how clean the camp was, especially early on, showing respect for both community and the land. Willis also included letters from students to President Obama, and a portrait he made of one student, Eden, holding a book open to a page with this quote from Camus: “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” During this period in our history, this quote seems more relevant than ever and not just for indigenous people.

The continuity of life throughout the generations was a motivating force for this movement and is evident throughout the book. It may also explain in part why women are the water protectors in indigenous cultures. In a piece about the water ceremony, which took place every morning at camp, Willis includes the following quote by Grandmother Mary Lyons, an Ojibwe water carrier:

“In ceremony we are guided by our ancestors that have already walked on. Water has memory, and if we disregard the water’s memory, we disregard life. So within these prayers we talk to that water, as if it were the umbilical cord that connects both worlds because their spirit lives within ‘this body’ that is made up mostly of water.”

©John Willis, ading With Police Officers in Mandan to Consider Water for the Health of their Children, Grandchildren, and All Future Generations

The importance of non-Native allies at Standing Rock and the numbers of people who took up the cause to protect water cannot be underestimated and may have contributed to the US District Court’s recent decision to order that the Dakota Access Pipeline cease operations with all oil to be removed by August 5th, 2020, until the Army Corps of Engineers can complete a real Environmental Impact Study.

©John Willis, Non-Native Allies Encircle Native Water Protectors to Protect Them From Possible Arrest and Harsh Legal Responses During a Street Action That Stopped Traffic Outside the Mandan County Memorial Courthouse

Though Water Protectors at Standing Rock were defiant in standing up for their rights by openly resisting the construction of this environmentally dangerous pipeline near indigenous land, nonviolence and prayer were at the center of their actions and they had daily ceremonies and trainings to reinforce this. The struggle went on for months and at times violence did erupt in response to aggressive tactics. In an essay on the Backwater Bridge, John says that though he does not want to justify any violent actions, he feels that “actions and reactions are more understandable when put into context of the larger story.” The confrontation came to a head on November 20, 2016, when Water Protectors were met with water cannons, rubber bullets, tear gas, concussion grenades, sound cannons, pepper spray, and beanbag bullets for more than ten hours.

Following the images from that night, Willis includes a statement by Harold C. Frazier, Chairman of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, in which he states that “the American government has failed us, the American people have not.” Veterans did not fail them either. A week after the Blackwater Bridge standoff, North Dakota Governor Jack Dalrymple threated to cut off all supplies. Army veteran Michael Wood, Jr. put out a call to veterans to come to Standing Rock in defense of what he and other veterans perceived to be over-militarized and unjust government treatment of people within their own country. Thousands of veterans came to Standing Rock in blizzard conditions. According to Wood, Native Americans have served the US military at a greater percentage than any other group in the country.

©John Willis, Native and Non-Native U.S. Military Veterans Defending the Water Protectors in Response to the Unwarranted Police Action at the Blackwater Bridge

It should be noted that the flying of the flag upside down is permitted as a signal of serious distress, according to the United States Flag Code.

The book concludes with a prose poem by Mark Tilsen called “Leaving Camp,” which expresses the emotions felt in the days, weeks, and months after the camp was closed down and Water Protectors left. There are also photographs of a collection of objects found at Standing Rock, as well as images of contemporary Lakota “ledger art” that comments specifically on the Dakota Access Pipeline. These objects and drawings serve to round out the record of what happened from the perspective of sovereign Indian Nations.

Shaunna Oteka-McCovey, an environmental lawyer, writer and poet penned the Afterward. Entitled “Responsibility, Resilience, and Reciprocity,” her words describe the work that needs to be done to educate people about the Native American way of life and our shared humanity and responsibility to future generations. Though the camps at Standing Rock were only occupied for less than one year, the movement created a model for future indigenous protests and the efforts of water protectors continue to be impactful. As Lucy Lippard states, “Standing Rock was not a failure, as some would have it, but a beginning.” This inspirational book shows how powerful non-violent resistance can be and champions solidarity as a path forward to a sustainable future.

John Willis (b. 1957) is a photographer who was a professor of art at Marlboro College from 1990 until his retirement in 2020. He has received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Photography and many other grants, and his photographs are in more than sixty collections, among them the Amon Carter Museum, Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, J. Paul Getty Museum, Heard Museum, High Museum of Art, Library ofCongress, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, National Gallery of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and Whitney Museum of American Art. His other books include Mni Wiconi / Water Is Life: Honoring the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and Everywhere in the Ongoing Struggle for Indigenous Sovereignty (George F. Thompson Publishing, 2019), Views from the Reservation: A New Edition (George F. Thompson Publishing, 2019; originally published in2010 by the Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago), and,with Tom Young, Recycled Realities (Center for American Places, 2006). Currently his collaborative book project Requiem for the Innocent, El Paso and Beyond is being printed. The book is a collaboration with writer Robin Behn and composer Matan Rubenstein (George F.Thompson Publishing 2020).

Artist Statement:

I had heard about resistance movements, led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe supported by non-Native allies, against the Energy Transfer Partners project to build an oil pipeline through the Dakotas, across Iowa, and into Illinois. In early September 2016 I headed west to witness the efforts of the resisters, or Water Protectors, as they chose to be called. Drawn to their dedication, I went to the Oceti Sakowin (“Seven Council Fires”) Camp in North Dakota, one of several camps set up to accommodate the resisters and their allies.

The 1,172-mile-long Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) would pass beneath the Missouri River just above the Standing Rock Reservation’s northern border. The tribe objected because any oil leak would go directly into the drinking water supply for both the reservation and millions of people living downriver, and because construction threatened tribal sacred sites in the area.

The Standing Rock Sioux filed suit in court to stop the Army Corps of Engineers from building the pipeline until a full environmental impact study could be done. When this and other efforts failed, the Mni Wiconi (“water is life” in the Lakota language) and NoDAPL (“No Dakota Access Pipeline”) grassroots resistance movements grew up.

Approaching Standing Rock, I encountered a National Guard roadblock with guardsmen carrying M16 rifles behind cement and razor wire barriers. Their purpose, they said, was to let travelers know there was a protest camp ahead.

At the Oceti Sakowin Camp entrance another security team, with neither weapons nor barriers, welcomed visitors to the camp and let them know that no guns, drugs, or alcohol were permitted; the camps were for nonviolent resistance through prayerful action. They requested that visitors check in at the media tent to learn the protocol if we intended to use any form of cameras, video, or media. They told us where to find the volunteer resource tent, kitchens, medical tent, and donations area.

An elaborate community had been set up in the camp, including a school for children, daily community meetings, a media group center, daily nonviolent action training, an art tent, and much more. Everything was free of charge—in traditional native fashion, money was not to be exchanged for services. The camps bustled with the energy of people wanting to help each other and assist in the cause.

I made six trips to North Dakota between September 2016 and December 2017, where I spent a total of eight weeks living out of a car at the Oceti Sakowin Camp. When I first arrived, there were estimated to be 500–700 supporters. On later trips I saw the camp size ebb and flow. At its peak around Thanksgiving, there were said to be 12,000–15,000. It is said that representatives from 240–300 native tribes, and many thousands of people from around the world, came in solidarity.

Around the camp’s sacred fire circle, people shared their reasons for traveling to support the cause. Although the news media barely mentioned the numerous pipeline leaks that occur annually in America, such leaks are extremely dangerous and difficult to clean up. In one such incident, in November 2016, a pipeline leaked 14,000 gallons of oil into the Ash Coulee Creek, a tributary of the Little Missouri River, near Belfield, ND. Another leak in November 2017 in South Dakota spilled 200,000 gallons in one day.

In sharing their own stories around the fire circle, people gave examples of fishing tribes whose waters became so polluted they could no longer eat the fish. Others told of communities that could no longer drink the water from their land, after allowing corporations or government to use their natural resources for fossil fuel or similar industries. One after another, people cited examples of the ways we are allowing corporate greed and human overconsumption to negatively affect our environment. We are killing the planet’s resources for future generations at a speed unsurpassed, solely because the desire for immediate profit is valued more than life for all generations. The movement was deliberately led by Indigenous people, but the cause is for all people.

Viewing the Mni Wiconi and NoDAPL protests as an isolated happening ignores the historical and cultural circumstances, and the recurring systemic practices, that led to the protests. Acknowledging the true, and complicated, situation can help us move forward in a better way. The call from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to resist the Dakota Access Pipeline was a call for humanity to recognize that our natural world is not an endless resource to be stripped without consequences for our actions. We must prioritize finding ways to live in harmony for the benefit of all, including the generations yet to come.

In service and solidarity, Oh Mitakuye Oyasin (“All My Relations”)

John Willis

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026