Photographers on Photographers: Macaulay Lerman in conversation with Paul Guilmoth

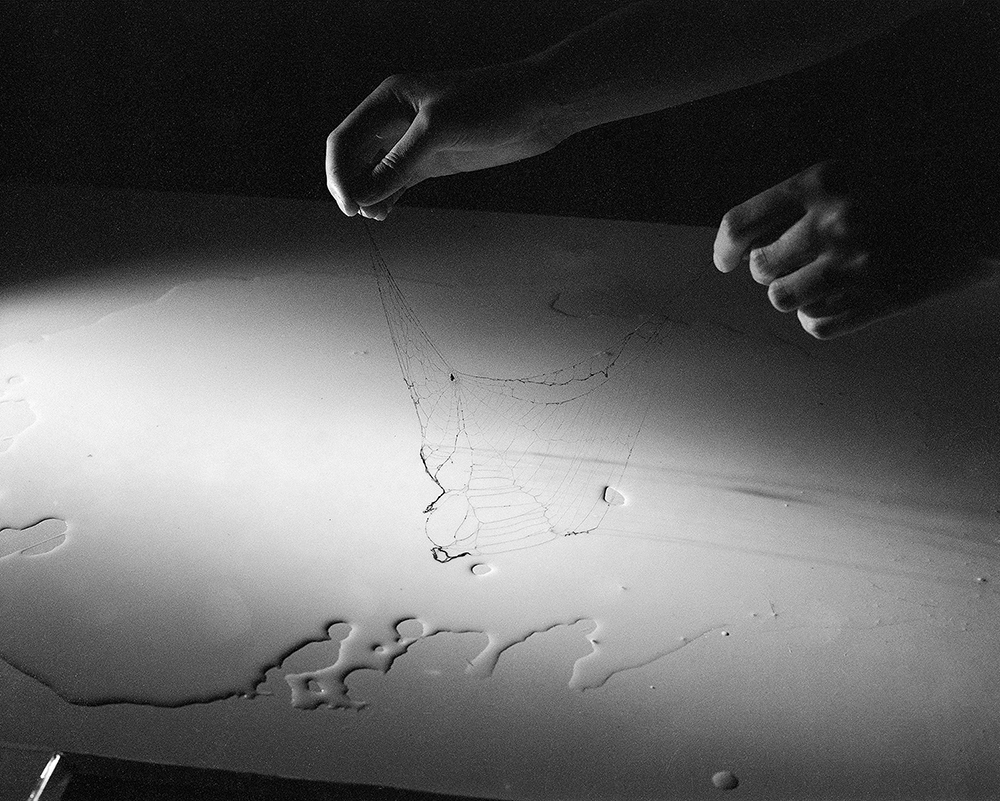

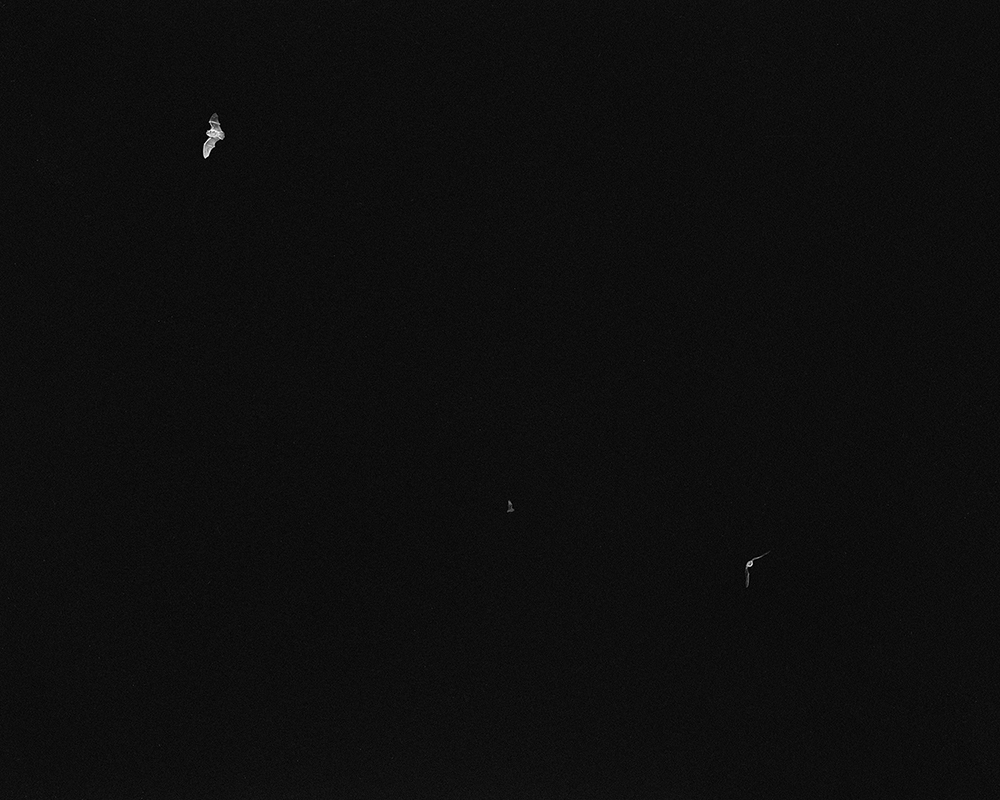

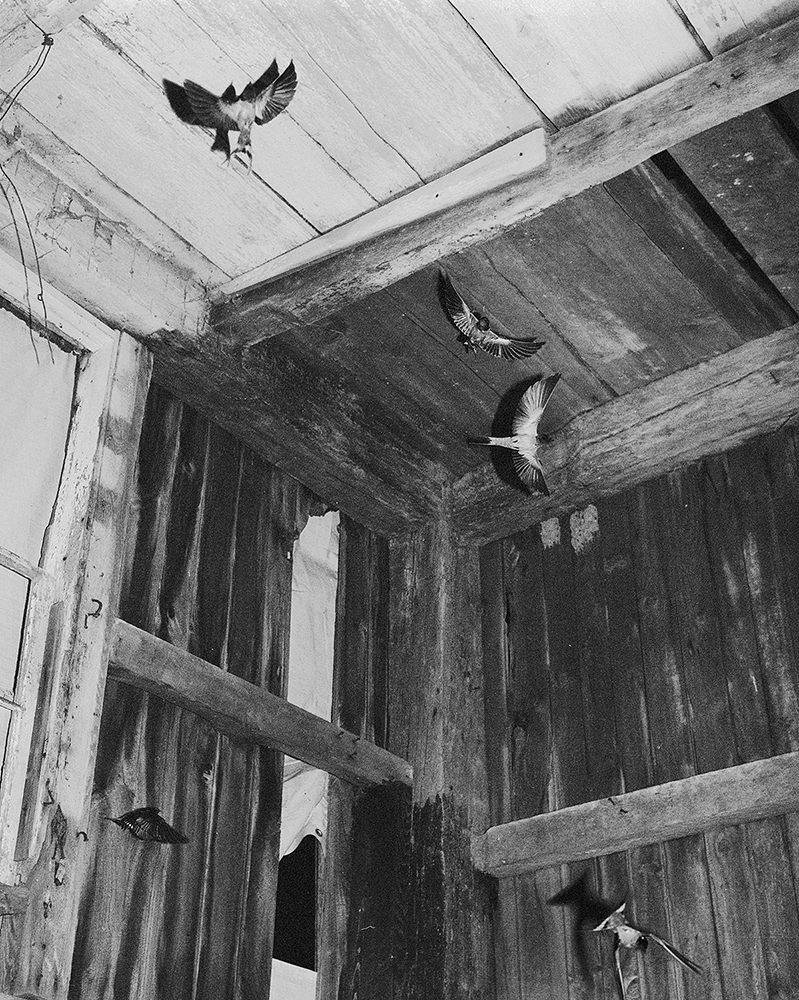

At first glance the photograph is a medium of great limitation. The primary function of the camera is to describe the surface of an enclosed scene. Yet, for perhaps ineffable reasons, certain imagery surpasses it’s technical purpose, instead conjuring sensations that span the senses and inspiring curiosity as to what lies beyond the frame. The work of New England based artist Paul Guilmoth does just that. Through the use of flash and black and white film, Guilmoth presents the viewer with a nocturnal realm equally obscure as it is ordinary. A jarring exposure catches a burst of birds in the chaos of flight within the walls of a decaying barn. A shielded figure enveloped by bedsheets drifts in slumber while ladybugs crawl across their tranquil form. Upon earlier encounters these scenes seemed to contain a macabre sensibility and impending menace. Yet as I view them today I’m struck by the relationship portrayed between humans and the natural world. In “Fresh Milk”, there is a sensuality to the way that two hands emerging from darkness drape cobwebs across spilled white liquid. In “Bending Down to Drink from Itself”, there is a tenderness between the flower and it’s holder as a blossom is bent gently towards it’s stem. It’s far too easy to equate the nocturnal with melancholy and peril, and while those elements exist here, the world of Egg White Moon is far more complex. Guilmoth’s work is at once a memory and a premonition, a perfectly described surface and yet a mystery.

Paul Guilmoth is an artist living and working in rural New England. They are focused on bookmaking, photography, and their intersections. Paul’s photographs utilize subtle levels of interference and performance that exaggerate uncertainty over truth, while describing a world strangely familiar and palpable.

Paul Guilmoth is an artist living and working in rural New England. They are focused on bookmaking, photography, and their intersections. Paul’s photographs utilize subtle levels of interference and performance that exaggerate uncertainty over truth, while describing a world strangely familiar and palpable.

Macaulay Lerman was born in the Spring in Southern California and raised in New England. As a young adult he traveled throughout the US and Canada hitchhiking, hopping freight trains, and driving his camper van. While Lerman rarely carried a camera during this time, he developed a practice of documentary storytelling through extensive journaling. To this day he remains fascinated by fringe communities and alternative ways of living, perceiving, and being in the world. While his process is largely ethnographic, in the sense that he immerses himself in the worlds he depicts, he is far more interested in emotional realities than hardlined physical truths. Above all else he values dreams and memory. A photograph exists somewhere between the two and this is why he is drawn to the medium. Lerman earned his BFA in Photography and Documentary Studies from Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. Since then he has shot for a variety of organizations including the Slate Valley Museum and the Vermont Folklife Center. His work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions, and featured in publications including It’s Nice That, Lenscratch, and Anywhere BLVD. Lerman currently resides in Burlington Vermont where he is an active member of the Wishbone Artist Collective.

Egg White Moon

For my ongoing project Egg White Moon I have stayed within the boundaries of two rural villages in New England: collaborating with my family and the landscapes they occupy. Land here is seen as a backdrop on which generations of monuments, hopes, traumas, and failures are erected and eventually laid to rest. I search for the physical and spiritual manifestations of unshakable inheritances and slowly shifting identities. Using methods of ‘the stage’, and my attempt to subvert documentary truth: my work describes a place and its ghost. – Paul Guilmoth

ML: I can recall the first time I encountered your work and being utterly mystified by the human subjects and surrounding landscapes they inhabited. You state in your bio that for your series Egg White Moon, you limited yourself to two small villages in New England, and worked exclusively with family members. Has your practice always revolved around photographing those close to you? Why is collaborating with loved ones important to your way of image making?

PG: There is a level of collaboration in photographing friends and family that allows me to feel okay with subjecting them to these worlds that I intend to build. Some of the scenarios are not staged and are taken while wandering or following my subjects around, but in the context of the greater fiction they are sentences, so I need to have them be on-board with that idea.

Around 8 years ago when I was starting to be serious about being a photo-maker I had very different intentions. I wanted to meet strangers and photograph this sort of removed interaction. I found out soon after that this wasn’t true to myself and the way I wanted to interact with the world.

ML: I’m curious about your influences outside of photography. Could you talk about any involvement you’ve had with other mediums, or non-art related experiences that have shaped your creative journey thus far?

PG: Most all of my influences lie outside of photography. Here is a list of a few of the things that are important to me;

Spiders: For the past three years I have studied the spiders that post up along the river and woods behind my home. The river banks have an abundance of Orb-weavers which I enjoy watching with a dim light after dark. In the hilly wooded parts, I look for bowl and dome shaped webs which trap the sunset really well, making them easy to spot. I often don’t bring a camera and just go to observe but I do have a slowly growing archive of very matter-of-fact photographs of webs that I am not really sure what to do with.

Angel Bat Dawid: The Oracle was released this year on International Anthem records. She is a self proclaimed “spiritual jazz soothsayer”. This album has already become a permanent fixture. Apparently she recorded everything on her Iphone and then stitched and collaged the fragments together to make this incredibly atmospheric journey. Her live performances are very different, but similarly amazing

Grouper: When I was in the 10th grade of high school I came across Dragging A Dead Deer Up A Hill on some obscure music blog. I would listen to it over and over so loud that it blew the speakers in my pickup truck (it may have actually been repeatedly listening to Dictius Te Necare by Bethlehem at full volume, which makes more sense, but I can’t remember). It changed my life forever until a couple years later when I found this home-made compilation of Grouper singles that featured the tracks Water People and Sick amongst about four others. I still get chills from Water People. I want to crawl inside and never leave.

Lieven Martens Moana: Around the same time, in the same manner, I came across one of Lieven Martens first recording projects by the name of Dolphins Into The Future. I remember being hesitant at first, not really familiar with music of this pace and atmosphere. breathtaking field recordings, mixed with slow, spatial synth parts. I forgot about him until I recently found his new album Idylls released under his own name. A gem.

Christine 23 Onna: Acid Eater had a huge impact on me in some unspeakable way. They are the Osaka-based duo of Masonna, and Fusao Toda (who was in Angel In Heavy Syrup). Really wild, noise-drenched, psychedelic music.

One Of You: I know nothing about this artist, separate from the bio featured in the liner notes of her self titled, and only, album. It sounds like it’s all anyone knows? Which is part of the allure. It was originally released in the 80’s and then recently re-released by Little Axe Records (an offshoot of Mississippi Records). A very haunting album with strange spoken-word storytelling and hypnotic organs. A must listen.

Joy Williams: I love everything Joy has ever done, even her Key West travel guide (which I felt the need to read even though I have never been to the Florida Keys, nor does it even exist as it did when she wrote it, I assume). Her most recent book, 99 Stories of God, features very short, sometimes disconnected, vignettes. She has mastered a humor that is dark, spiritual and totally absurd.

ML: The titles you select for your projects are always highly evocative and darkly imagistic, yet I don’t see further writing or poetry interwoven throughout your images. What is the function of the written word within your work?

PG: Titles exist somewhere between narration and description, so I either like to be vague enough to conjure ideas outside of the frame, or self explanatory, so that you’re only paying attention to what’s inside the frame. Text is so important to me and I am currently trying to find new ways of utilizing it in my practice.

ML: In terms of composition and content your photographs feel so precise. Do the scenes you depict reference events from stories you’ve heard or perhaps your own history?

PG: Yes and no. Yes, because I feel as though everything I make is a response to all of my personal and learned experiences in life. And no, because memory is ultimately a failure and the photographs I make, the “staged” ones, mostly reference images birthed in my head that have no placeable origin. Often, I am curious how something will appear in the physical world, so I make it and only afterwards does it, maybe, serve some buried experience. I am also very interested in learning the histories of the places I live and photograph. I can’t imagine existing in New England without being aware of its tragic histories—where I am now is actually Pocomtuc Land.

ML: Your approach to making images relies predominantly on the use of flash in a nocturnal setting. How did you arrive at this way of working?

PG: The night allows me to obscure the parts of the landscape I am uninterested in. At night you can pick and choose what to illuminate. I am not a daylight person and I try to avoid most places when the sun is shining high. The river here attracts people during the day, and at night there isn’t a human in sight, naturally. It’s a great time to listen and observe.

ML: How essential is the New England landscape to your work? What about life in the North East stimulates your imagination and creative impulse?

PG: For generations my family has lived in the same old village. 99 percent of me is certain that I will die where I was born. Then continue to haunt the land or something. I really appreciate how much slower life feels in rural settings. I don’t need change and constant stimulation. I like looking at the same trees, stream, and field everyday. Outside of the cities you can find very cheap rent, which is necessary for me. I realize the immense privilege in this. Feeling safe enough to stay, to not need change. Though there is also a privilege in traveling, or leaving someplace for the sole reason that you’re going stir-crazy. I work in New England because, for some reason or another, i’m afraid to leave just yet.

It’s worth saying that I also find this place to be immensely beautiful and I want to be here.

ML: I know your practice has an emphasis on bookmaking. What appeals to you about the photobook as an art object?

PG: Since I was little I have been obsessed with mobile objects. Growing up in a family of antique dealers there were always, and still are, objects of mysterious origin displayed, and in boxes. I would spend hours going through them just to feel all the textures. I still do. I started a small collection of these staircase baluster knobs with these haunting faces painted on them.

In other objects, books are an entire world that you can carry around. In my current world, art doesn’t exist in any other way. I don’t live anywhere near an interesting gallery, so for now it’s only books. I forget that art exists in any other form. The cost of books is very limiting so I really have to choose just a couple per year.

ML: You and your creative partner Dylan Hausthor’s first monograph, Sleep Creek, was released this past Winter. Some of the images displayed in Sleep Creek also appear in Egg White Moon. What are the intersections between these two bodies?

PG: Yes! I see books as a very separate entity. Sleep Creek solely exists as a book for now, so for the sake of my website “gallery” I don’t mind double-dipping. Another point that seems fitting is that I feel as though I will always be working on the same project. I can separate things with titles but ultimately it’s just all one big body-of-work with new chapters being added at different stages of my life.

I always like when musicians put a different edit/version of a past song on a new album. I think the photo world places a lot of emphasis on the idea that each photograph needs to be precious. I want to unlearn that toxic idea.

I’ve never been “assignment” oriented; like picking a specific subject and trying to make work about it. I’m drawn to art that is an extension of its maker and that changes with their life and experiences. I work on intuition and then find an aesthetic thread that ties it all, or some of it, together.

ML: Anything new to announce? What’s next on the horizon?

PG: I have some new work in process at the moment, which should be up on my website, in part, by the time this is up.

Those of us who are receiving an income, or have extra money these days should be continuously putting some of it towards reparations for BIPOC artists and individuals. I have been using https://www.theradicaldatabase.com/ as they seem to have the most complete list of resources, petitions, literature, and fundraisers.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026