Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Smith and Jade Rodgers in conversation with Nakeya Brown

I first came across Nakeya Brown’s work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. One of the things that I really love about that place is the educational programming that they provide for free to visitors. At the time I was teaching at Chicago State University and had brought my students to the museum for one of their print viewings. Nakeya’s work was included in the work pulled for the viewing and I immediately saw my students gravitating towards it. From there I started following Nakeya’s career and have continued to show her work to students. If you’re not immediately pulled in by the color, the carefully arranged objects place you somewhere that is not quite the past and not quite the present. In December I reached out to a group of artists to be part of the first exhibition at Study Hall, a gallery in the photography studios at PrattMWP that brings a diverse array of contemporary photographic work directly to students. I really wanted Nakeya to be part of this first exhibition as I had seen first-hand the effect her work had on my students previously. She thankfully agreed and so we were able to live with her work during the spring semester. In the spirit of Study Hall, I’ve invited my student Jade Rodgers, who has been making some incredible work about her family, to interview Nakeya with me.

Nakeya Brown was born in Santa Maria, California in 1988. She received her Bachelor of Art from Rutgers University and her Master of Fine Arts from The George Washington University. Her work has been featured nationally in recent solo exhibitions at the Catherine Edelman Gallery (Chicago, IL, 2017), the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art (Grand Rapids, MI, 2017), the Hamiltonian Gallery (Washington, DC, 2017) and The McKenna Museum of African American Art (New Orleans, LA, 2012); and in group exhibitions at the Eubie Blake Culture Center (Baltimore, MD, 2018) the Prince George’s African American Museum & Cultural Center (North Brentwood, MD, 2017), and the Woman Made Gallery (Chicago, IL 2016 & 2013), among several others . She has presented her work internationally at the Museum der bildenden Künste (Leipzig, Germany, 2018) and NOW Gallery (London, U.K., 2017). Brown’s work has been featured in TIME, New York magazine, Dazed & Confused, The Fader, The New Yorker, and Vice. Her work has been included in photography books Babe and Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze. She lives and works in Maryland with her daughters Mia and Ella.

Sarah Phyllis Smith (b. 1986, Middletown, NY) is a photographer and educator based in Utica, NY where she is Assistant Professor of Photography at PrattMWP. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions include Where the Great Lakes Leap to the Sea at The Shed Space in Brooklyn, NY and Fish Hotel at Vanderbilt University. Her work has also recently shown at Perspectives Gallery at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, Ground Floor Gallery (Nashville), Whitespace Gallery (Atlanta), Roman Susan Gallery (Chicago), Wedge Projects (Chicago). Her work has been featured by through several online and print publications including Musée Magazine, Silver Eye Center for Photography, From Here On Out, Don’t Take Pictures Magazine, Vulgaris Magazine, and Incandescent Magazine, and was featured on the cover of Iranian literary magazine, Dastan. Sarah is also the curator of Study Hall, a contemporary photography gallery at PrattMWP.

Jade Rodgers (b. 1997, Suitland MD) raised in Stone Mountain, GA. She is currently pursuing her B.F.A at Pratt Institute in New York. Jade’s work has been featured in group online exhibitions, Togetherness, with the Houston Center of Photography(2020), The Study Hall gallery, Curated by Sarah Smith at PrattMWP(2020), as well as Earth Mother/ Mother Earth, Don’t Smile(2020), and Interviewed by Cumulus Photo (2020). Her work has been previously shown in group exhibitions at the Bazzar Noir (Washington D.C, 2016), Cir De So ‘90s (Washington D.C., 2017), and most recently in her Sophomore show at PrattMWP (Utica, NY 2020). Jade continues to make work from home in Maryland, as a freelance photographer.

Sarah Phyllis Smith: Can you tell me a little about yourself? What has your trajectory into photography looked like?

Nakeya Brown: I was fortunate to take my first photography class as an elective my senior year in high school. From there I went on to study Art & Journalism at Rutgers University before completing my MFA studies at George Washington University some years later. Currently I am an active exhibiting artist, freelance photographer, and secondary/post-secondary photo educator.

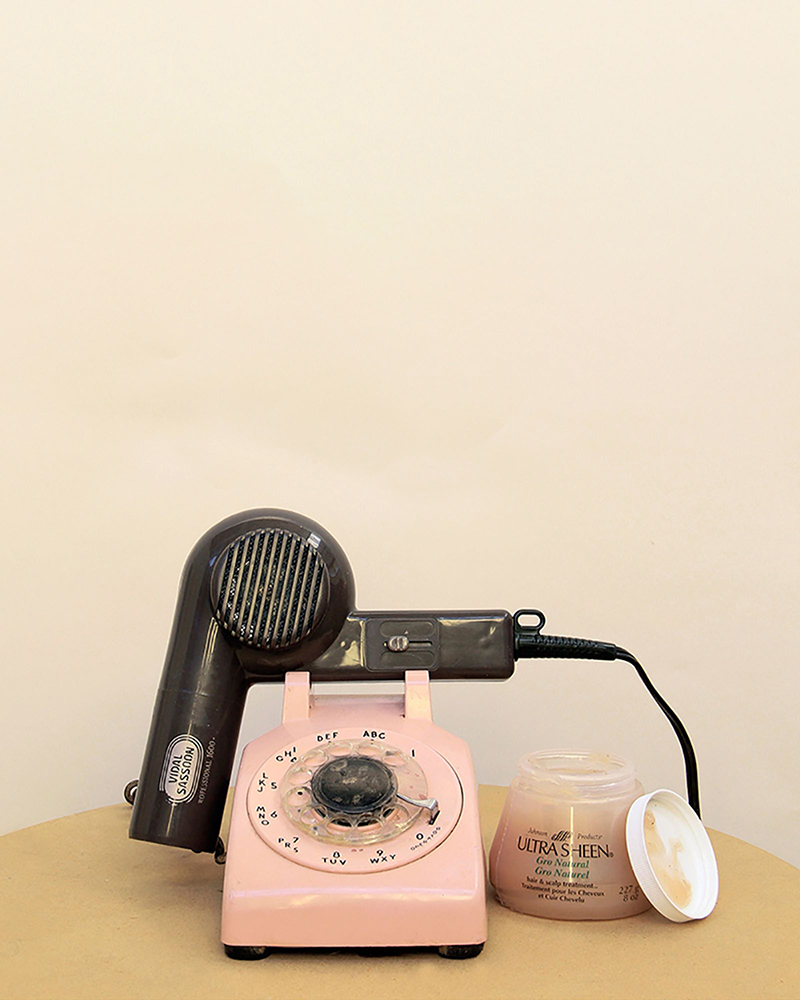

© Nakeya Brown, Don’t You Know Love When You See It?, If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown, Archival Inkjet Print, 2014

SS: Can you talk about how ceremony and intergenerational rituals operate within your work?

NB: Intergenerational rituals were a way to explore the idea of beauty through the lived experiences of Black women. I almost always imagine my photographs through periods of the past via personal and public memories of Black women. Many of the memories I’ve used are from the ritual of hair care amongst and between Black mothers, daughters, aunts, cousins, grandmothers, friends, etc. The beauty practices, shared histories, and tangible things that have sustained themselves through generations of womanhood became my subject matter in and of itself.

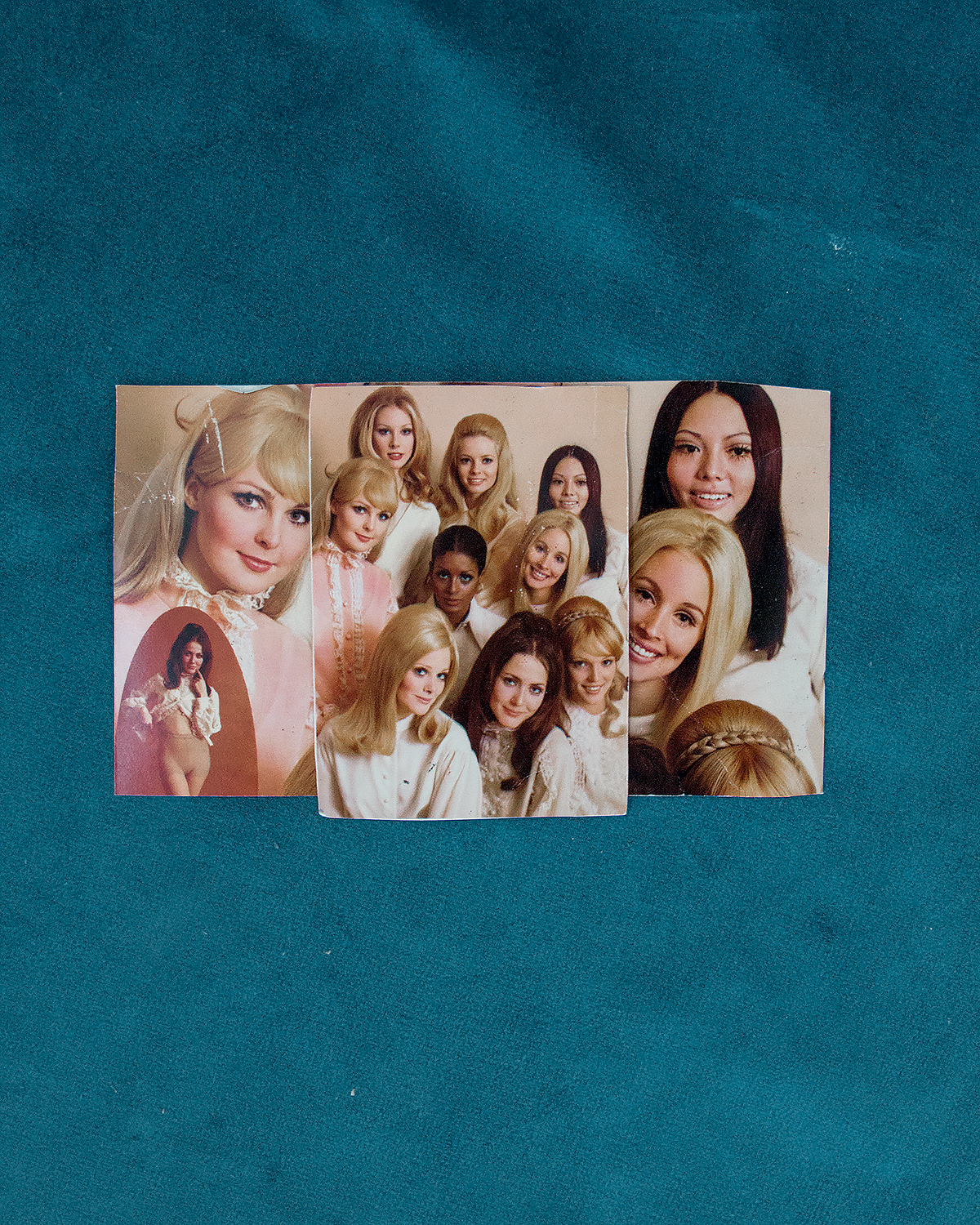

© Nakeya Brown, Almost All the Way to Love, If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown, Archival Inkjet Print, 2019

JR: Could you possibly talk more about your relationship with family members and how their hair standards impacted the way you saw yourself?

Like most, I saw myself through the styles and practices that circulated among the women in my life. Wearing braids, perms, and Afros were the most prevalent views I’d see. Through my family I’ve been able to witness self-fashioning as a form expressing pride and connection. It wasn’t until I got older that I started to understand that these practices have political implications—that early on the women in my family were working to resist several standards that negatively impacted Black women and girls.

SS: You’ve been very open in other interviews about your transition to wearing your hair naturally and in moments the images could read as shrines to the products and accessories associated with the manipulation of Black hair. Are you thinking about the works as a celebration of this history or an indictment of it? Perhaps it’s neither and falls somewhere in between.

NB: I consider “if nostalgia were colored brown” to be a celebratory series centered on Black womanhood and rituals of care. Much of my practice is making space in the literal and contextual sense. The photographs in that series visualize fictional interiors that illustrate the way space can be constructed as a representation of Black beauty. I staged these imagined tableaux with old blow dryers, combs, grease, satin scarfs, and rollers—many of these items carry a personal tie to the dresser tops and powder room items I’d see growing up or keep in my own place. In part it is about affirming the right to perform self-care through the ritual of Black hair care.

“Facade Objects” is more critical of the hair industry and the way it saturates Black women with the idea that straight hair is a standard way to achieve beauty through the contested practice of perming. Another series, “The Refutation of ‘Good’ Hair” also examines how Western ideals of beauty do little to protect Black womanhood. I think there are many layers to the work I create because the history of Black hair is rooted in cultural expressions but is often judged against Western hegemonic perceptions within society.

SS: There is a history of beauty products that you’re channeling with your formal choices in the work as well. I was recently looking at interior photographs of the original Ebony/Jet Building in Chicago and your colors feel pulled right out of their offices. It seems like you look at these objects and products fondly but through color are always placing them somewhere in the past. How do these formal choices lean into the conceptual root of the work?

NB: I look to the available pallet of the objects and the other accoutrements to help construct the space before photographing it. The psychology of colors and their emotive potential is also at play as I am building my work. I’m actively seeking to evoke joy, nostalgia, and criticality. Typically, I begin with a singular object that I find striking and build around it. It will typically be an item with known symbolism because of my interest in representing female subjectivity without the literal of a figure exclusively. Early on I used vinyls depicting Diana Ross, Deneice Williams, Minnie Ripperton, and Natalie Cole. Their careers span decades, but many hit the scene in the same era as the Black press and media outlets began to market a collective Black female identity as something to be widely desired. As I made my work it was with an understanding that Black women carry a certain iconic and symbolic presence within the public realm.

SS: When I look at your work I’m immediately brought into the present as well. I’m thinking about the criminalization of Black hair but also discriminatory practices by some retailers to place beauty products made for POC behind plexiglass. It’s hard to not think of beauty and its relationship to consumerism and capitalism in your work. Can you talk about how the politics of hair are at play in you work?

NB: For me, hair politics can work as a metaphor for how Black women have been negotiating and fighting for the right to exist beyond the repressive notions within society. Present day policies like the CROWN Act are still necessary because the Tignon Laws once existed to suppress Black women from even showing their hair publicly. Across my photographs there are protective tools like scarves, bonnets, wraps, and protective styles like braids. These are mechanisms practiced by Black women to resist the lingering effects of targeted suppression. It allows room for cultural expression, artistic expression, and ancestral recognition. I think of my practice as a small collection of different entry points for my lived experiences and the experiences of others that are contextualized by the strands of our histories.

© Nakeya Brown, Seeing Less Than Half the Picture, Gestures of my ‘Bio-Myth’, Archival Inkjet Print, 2015

SS: Your work tells stories about womxn, for womxn, and made by a womxn. Can you talk about your work in the context of intersectional feminism?

NB: My work has looked to the knowledge production that is created out of Black feminism. The series “Gestures of my Bio-Myth” borrows the name from Audre Lorde’s concept of the “bio-mythography” or a form of storytelling where actual occurrences of the past are coupled with imagined details. Within that work I am actively using inventive remembrances of my past as a way to create new photographs. Just as intersectional feminism seeks freedom out of race, class, gender limitations—that body of photographs are actively using the image to visualize a type of freedom from previous representations of Black female subjectivity within photography.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectional feminism considers how our experiences as women are nuanced even within the collective feminist struggle. Reading the writings of Black women such as bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Patricia Hill Collins has helped me to better understand that considering the multiple identity categories we embody reveals unique viewpoints that are often overlooked. I am interested in how I can transfer that unique viewpoint into photographs.

SARAH: Can you tell us what you’re working on now? I’ve been following your work for a few years now and you’re very deliberate about when and what you release. Any sneak peeks into what’s happening in your studio?

NB: I just completed an Artist Mother Studio residency and will be completing the Sibyls Shrine Residency for mothers that identify as artists. I will be presenting a solo exhibition of works at the Delaplaine Art Center in the fall and another at Davis Gallery in early 2021.

JADE: What advice would you give to young Black womxn struggling with self-acceptance?

NB: I would encourage young Black women to think of self-acceptance through the act of reclaiming your full existence. Actively reclaiming your full existence can be so many things. It might be reading, talking, creating, studying, walking, dancing, crying, protesting, or writing—whatever it is, it is worthy.

Keep up with Nakeya here.

Keep up with Sarah here.

Keep up with Jade here.

Keep up with Study Hall Gallery here.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026