Spirit: Focus on Indigenous Art, Artists, and Issues: Donna Garcia

“‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Indian removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

Some months ago, I heard Donna Garcia discuss her project, Indian Land for Sale, as part of the Project 2020 Exhibition at the Los Angeles Center of Photography. I was deeply moved by her lecture and reached out to see if she would consider taking on the role of Editor for an Indigenous Issues Week. The answer was a definitive yes. I am so grateful for her time, commitment, and deep consideration of the projects she shares this week. Today, we celebrate her work, Indian Land for Sale.

Tomorrow, we celebrate Indigenous People’s Day and continue that celebration for the rest of the week with Indigenous artists she has selected. In addition we are coordinating our efforts in conjunction with the National Center of Civil and Human Rights. Today at 12pm EST, Donna will be in conversation with selected artists through the National Center of Civil and Human Rights. You can sign up here. There will be another conversation on November 14th.

Donna describes her curatorial focus for Spirit: Focus on Indigenous Art, Artists, and Issues:

“In 2018, I created my series, Indian Land For Sale. I thought it would be a straightforward conceptual series based on the devastating consequences of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the histories that surround it. As I began my research, I discovered that there was literally no original documentation around this event. I went to local archives, museums, even the area where the Trail of Tears began in Georgia – nothing but apologies. I was very frustrated, but I am not sure why I expected it to be different, because the ultimate goal of genocide is to wipe out all traces of a culture. That is when my project became about replacing what had been omitted from history.

Indian Land For Sale made me think deeply about the bias of history in North America. So when Aline Smithson asked me to host a week of Indigenous Art, Artists and Issues on LENSCRATCH, my goal was to feature a group of artists who represented a broad scope of lens-based perspectives, from icons to innovators.

As I curated this amazing group of artists, what struck me as strange, was that I hadn’t seen their work previously in my exploration of Contemporary Artists. Why had I not been introduced to the work of icons like Will Wilson or Shelley Niro? While all of the artists who will be featured/exhibited make work around indigenous issues, beyond that they need to be included in today’s photographic conversation, their work is compelling, distinctive, imaginative and impeccably executed. It’s important to know what the icons know, what the visionaries see, what the searchers have found and how the innovators create and how, as a collective, they will change the paradigm of history moving forward. You need to know these artists because their visual perspectives have the potential to reshape, retell, and rewrite the history of North America – now is the time.”

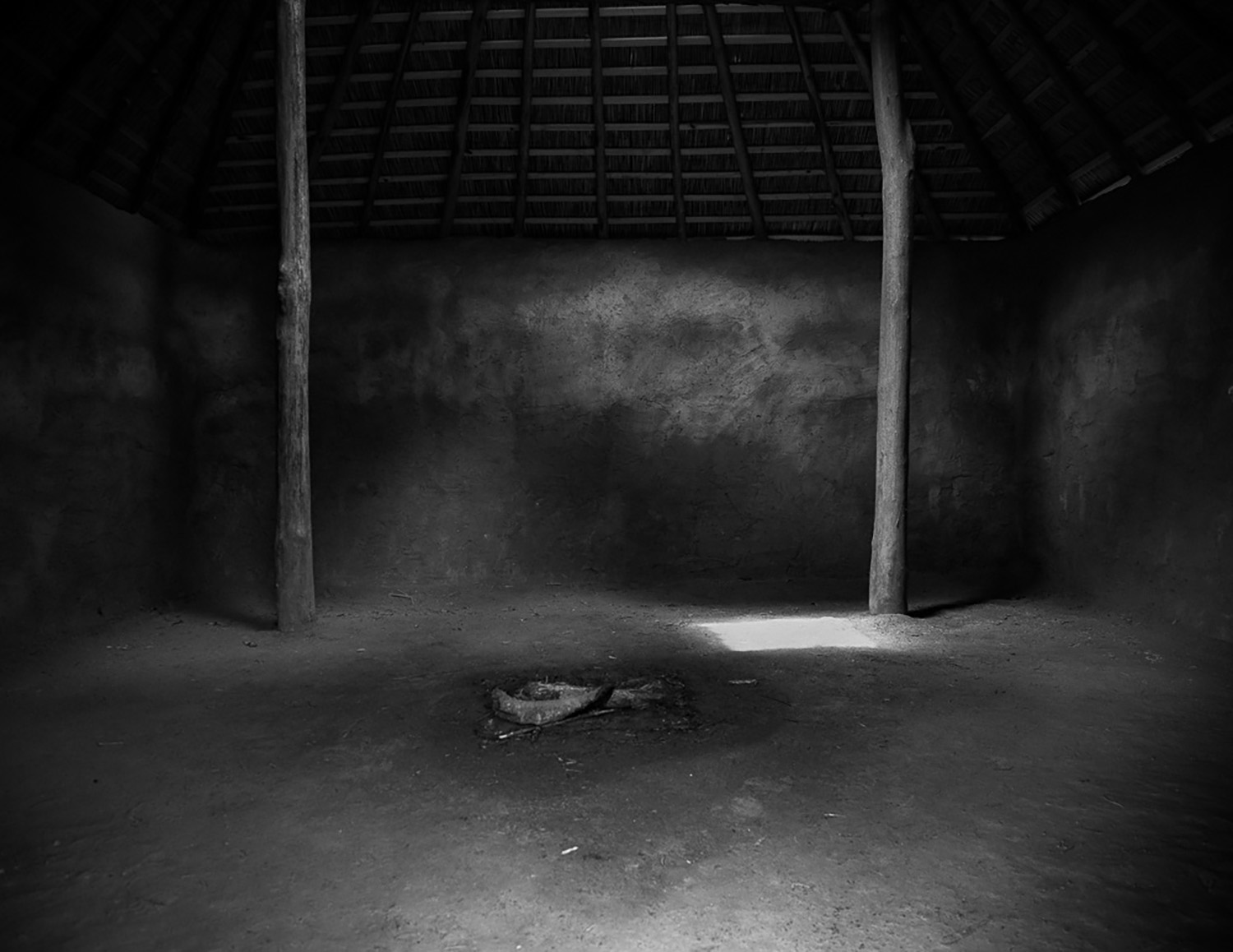

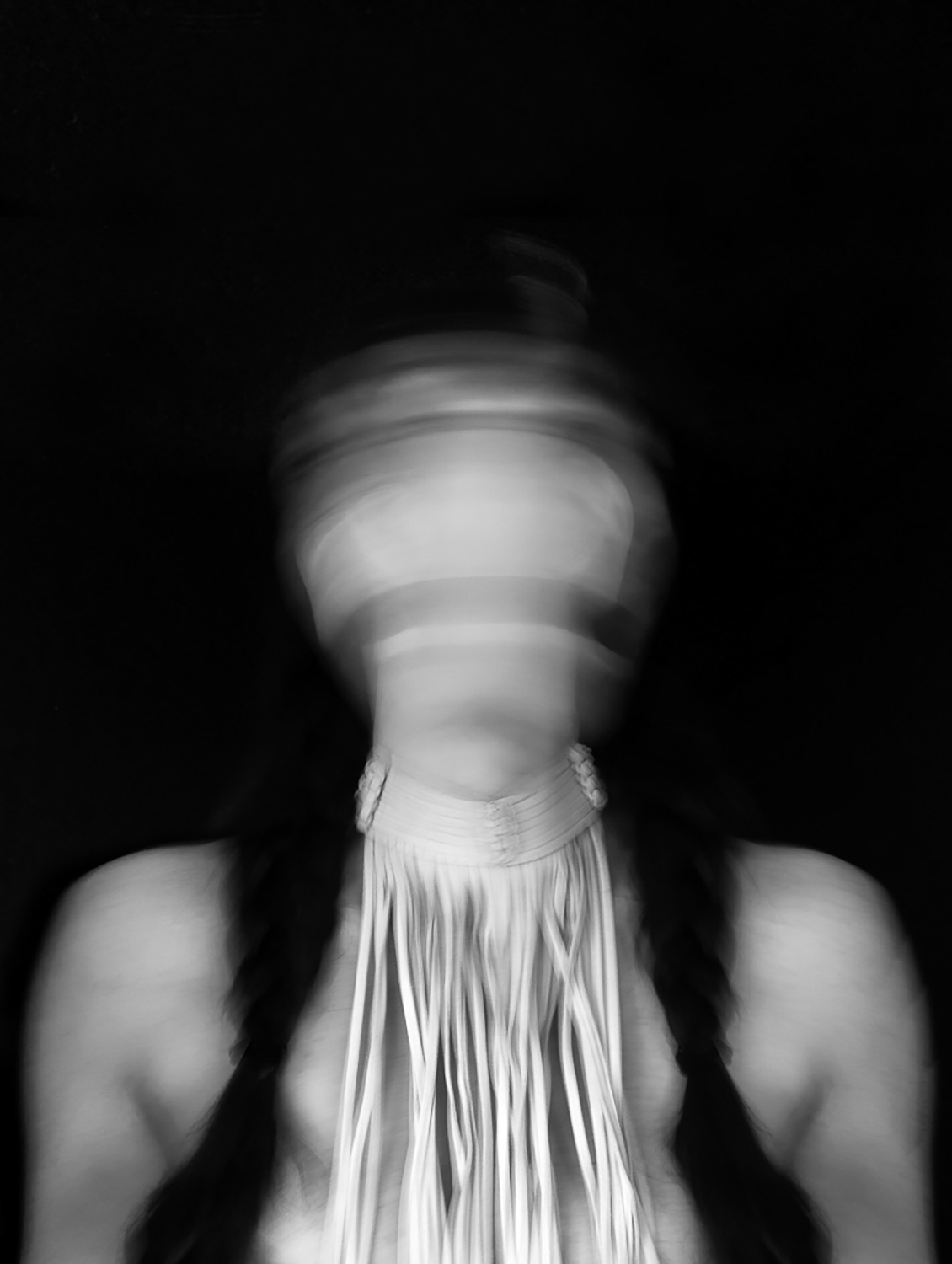

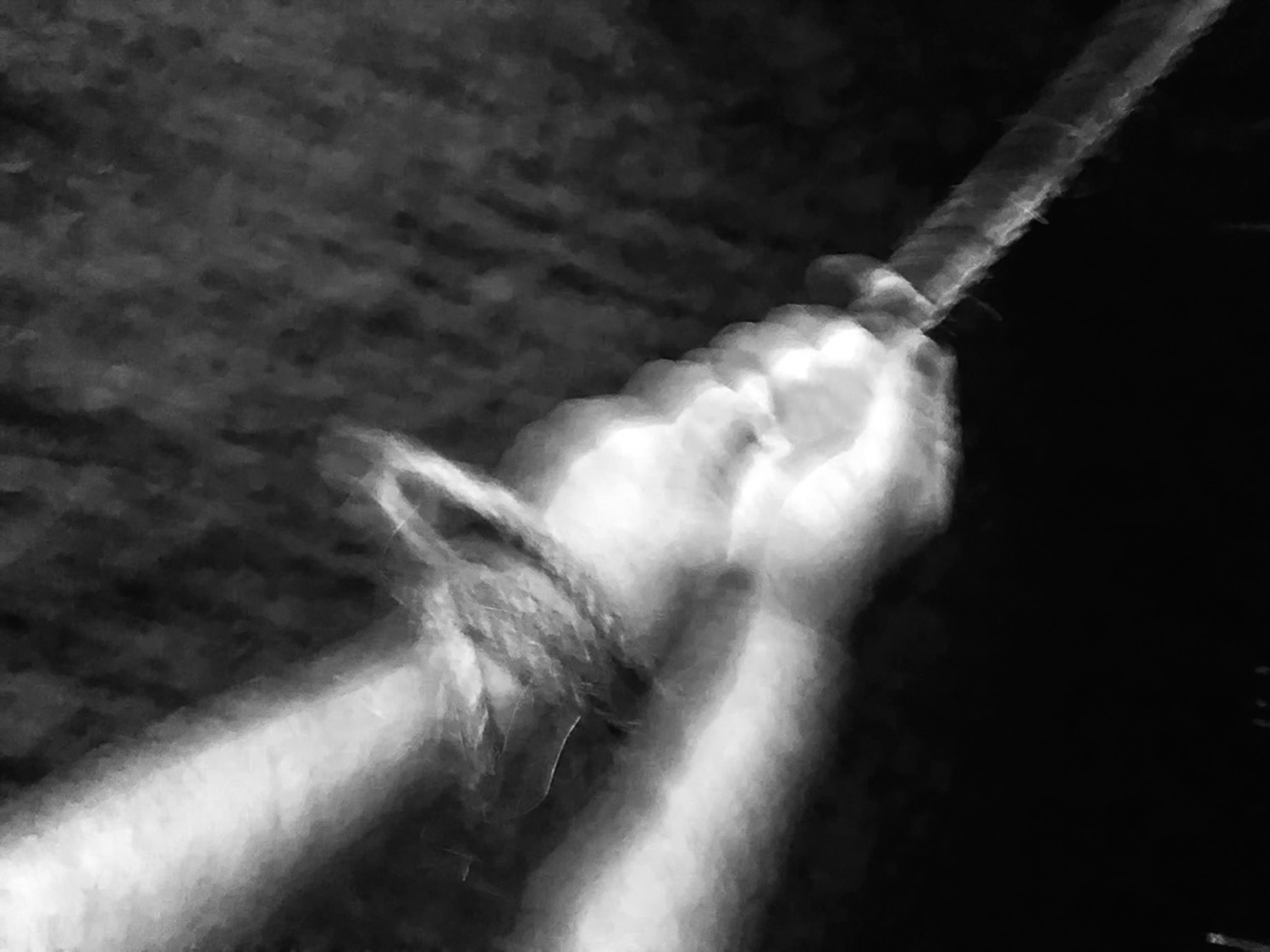

Her project, Indian Land for Sale, is a metaphoric and gestural expression around the ideas of pain, memory, and trauma and attempts to recreate the horror of this event from the perspective of the native tribes.. These ghostly images serve to replace what has been lost from official historical archives and seeks to sound an alarm, as the federal government, in 2020, is revoking ancestral land from protective trust.

Donna Garcia’s work illustrates a semiotic dislocation that has been organically reconstructed in a way that gives her subjects a voice in the present moment; something they didn’t have in the past. Her images rise above what they actually are and become empathetic recreations in a fine art narrative. She has an MFA in Photography from Savannah College of Art and Design and her work has been exhibited internationally. She is a 2019 nominee of reGENERATION 4: The Challenges of Photography and the Museum of Tomorrow. Musee de l’Elysee, Lausanne, Switzerland. Emerging Artists to Watch, Fine Art Photography, Nomination (only 250 lens-based emerging artists nominated worldwide).

Indian land for sale

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act was enacted along the East Coast of America.

President Jackson declared that Indian removal would “…Incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier. Clearing Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi of their Indian populations would enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power.”

Systematic hunts were made to force indigenous people from their ancestral land.

A Georgia volunteer, later a Colonel in the Confederate service, said, “‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Indian removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

Following the signing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations from their homelands to “Indian Territory” in eastern sections of the present-day Oklahoma. It was a 1,000-mile walk and took 116 days from Georgia, walking all day and only being allowed to stop at night to bury their dead. This is what we now know as the start of the Trail of Tears.

Not all indigenous people left in 1830, specifically the Cherokee. Many stayed, thinking that they would be allowed to live peacefully or have the ability to fight back (actually winning several legal battles against the removal order). However, the Georgia State government and Andrew Jackson, had plans for their land. Flyers began to circulate hailing “Indian Land For Sale”. White farmers flocked in droves to auctions of indigenous, ancestral land that was still, up to 1838, being occupied by its native people.

It was in 1838 that 7,000 US soldiers in Georgia enforced a final evacuation. The Cherokee, Creek, Shawnee and Choctaw villages were invaded and the people were forced to leave, at gunpoint, with only the clothing on their backs.

For the few who resisted, approximately 1,800, died while imprisoned for refusing to leave.

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of known cholera epidemics, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, 8000 Cherokee died, about half the total population. Half of the Choctaw nation was wiped out and 1 in 4 Creek.

A Cherokee survivor of the trail told her granddaughter, “The winter was very harsh and many of us no longer had shoes. Our feet froze and burst, as we left bloody footprints in the snow. We were not allowed to stop to bury our dead. Many mothers carried their dead children, miles, until we stopped at nightfall. All night you could only hear digging.”

The deportation of indigenous tribes along the Trail of Tears was an act of genocide that has been conveniently forgotten today. On March 27, 2020, the federal government of the United States revoked reservation designation for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe and has removed their 300 acres of ancestral land on Cape Cod from federal trust. This recent government land grab is raising grave concerns among indigenous advocacy groups across the country that all tribes could now be at risk – again.

To help go to https://sign.moveon.org/petitions/stand-with-the-mashpee.

Thank you so much for being our Editor this week and sharing such an amazing group of artists. How did you select the artists for this week?

It has been an honor to work with you for this project, and to be able to introduce your viewers to the work of these amazing lens-based artists. I am also grateful that through an exclusive partnership between LENSCRATCH and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, the artists featured here will be exhibiting this work at the (NCCHR) and be included as part of Atlanta Celebrates Photography (ACP).

The number one goal regarding the selection process was to have high quality work that addressed a variety of perspectives. Indigenous artist don’t just have one thing to say, and like all artists their projects аre based on their experiences, which can be influenced by the time the work was created, place and memory.

The artists being featured this week represent icons, visionaries, searchers and innovators from across the US and Canada, fully dedicated to photography and filmmaking as their primary medium.

As I started to discover the work of this amazing group, what struck me as strange, was that I hadn’t seen their work previously? How could I have not been introduced to the work of Will Wilson or Shelley Niro at some point? While all of the artists who will be featured/exhibited make work around indigenous issues, beyond that YOU NEED TO KNOW THEM because their work is captivating, powerful, inspirational and impeccably executed.

You need to know what the icons know, what the visionaries see, what the searchers have found and how the innovators create and how, as a collective, they аre poised to change the paradigm of history moving forward. You need to know these artists because their visual perspectives have the potential to reshape, retell, and rewrite the history of North America and now is the time.

Let’s start at the beginning and find out about you and your growing up? When and why did you come to photography?

I have always been an artist. I was just not a very good painter or illustrator compared to my contemporaries. I found photography when I was twelve years old and used an old Rolliflex to photograph throughout high school. I studied under photographer Walter Scott while in high school, but by the time I got to college I knew that I needed a consistent income after graduation, so I changed paths and became a creative director before coming back to photography five years ago.

I came back to it because I really could not suppress my artistic nature any longer. I was at a place in my career where I was very successful, but not very happy and it was physically making me ill. Photography is how I see and without it I am blind. It is a way to navigate life for me.

When did you begin to research this project and what was the purpose of the work, considering your own Indigenous lineage?

Much of my work could be described as historical recreations in a fine art narrative with a focus on oppressed historical groups of people, specifically women. The goal being to give them a voice in the present, something they did not have in the past. When I was asked to create imagery for a show about the history of Atlanta in 2018, I decided to focus on the Indian Removal Act in Georgia. Doing a project that you have a personal connection to is very difficult and complex emotionally, but I am pleased that it has created a renewed awareness of the genocide that happened here.

The impetus behind your project, Indian Land for Sale, is truly disturbing and eye-opening. Why are these terrible histories not part of the conversation?

Colonial genocide was a success. The goal of genocide is not just to physically wipe out a group of people, but to eradicate their entire culture. In doing my initial research for Indian Land For Sale, I was saddened (and annoyed) to discover that there were no local archives that even mentioned the Indian Removal Act of 1830 or the Trail of Tears. These events had been completely omitted from local history and now just existed, as some blurred narratives, not real historical events. The white men who drafted our history, in general, conveniently excluded their transgressions, so Indian Land for Sale was a created to replace what had been removed from the historical archives, but this time from the point of view of the Indigenous people.

Also can you speak to the work itself, what was your aesthetic approach in telling this story?

Stylistically a lot of my work deals with liminal space and the subject within it. Liminal space is that moment in time and space where the viewer sees themselves and the other (people or things not like them) at the same time, allowing them to feel empathy for the subject. Muscogee is a great example of liminal space in my work. I am able to slip outside of the rigidity of “the norm” by creating these unstable images in which the subject operates through two points, in a kind of in-between space. This method for creating imagery allows for a visual kind of Parapraxis to manifest. The work is allowed to create itself, in camera, with little to no postproduction. Through the use of manipulated exposure, motion and light/shadow influence, it crosses the threshold where subject and object become one. A transcendent moment is created, like a slip of the tongue, when a repressed truth is revealed.

I utilize self-portraiture and animism to reveal the self as a stronger potential that does not correlate with a bounded social order and my subjects don’t abide by rules.

Mood is created through abstraction, done in various ways, causing an inner reality to be exposed when the appearance of certainty is eroded. When things shift from secure and safe to a reality that is indeterminate. By abstracting what is recognizable to the viewer, forms detach themselves from their literal nature and are then capable of isolating the most significant expression within their meaning.

Has creating this project, and editing this week of artists, made you even more determined to continue the work?

It has made me more determined to elevate lens-based indigenous work and continue, through partnerships, to bring indigenous issues to the forefront. The work being featured here this week and on exhibit at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, is stunning and deserves a high level of permanent exposure. If establishments have the courage to show contemporary indigenous work and assimilate it as part of permanent collections that will help us to rewrite history. My hope is that more organizations and individuals step up to support indigenous issues as ancestral lands and native people аre still under attack everyday in the US and Canada.

What is next for you?

Currently, I am creating a series about our country’s history of reproductive violence against women.

In addition, there has always been a second part of Indian Land For Sale, which is a mixed-media installation piece. I have been working on it, off and on, for two years. I hope to complete that soon.

I am also the co-founder and co-host of the Modern Art and Culture podcast and looking for more ways to use my overall skill set to elevate indigenous issues, mentor women and support myself in the process – always a challenge as an artist.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

Right now, it is a day without a mask, a day that I can hug people, and a day that I can travel home.

Under non-Covid-19 circumstances, it is any day where I can find peace in nature with my camera and be with people that I love, which is super cliché but true.

About the National Center for Civil and Human Rights

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights is a cultural institution and advocacy organization located in downtown Atlanta, Georgia. Powerful and immersive exhibits tell the story of the American Civil Rights Movement and connect this history to modern struggles for human rights around the world. The National Center for Civil and Human Rights has the distinction of being one of the only places to permanently display the papers and artifacts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Events, educational programs, and campaign initiatives bring together communities and prominent thought leaders on rights issues. For more information, visit civilandhumanrights.org and equaldignity.org. Also sign up for Campaign for Equal Dignity!

Join the conversation on @ctr4chr (Twitter), @@ctr4chr (Facebook), and @@ctr4chr (Instagram).

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026