S. Billie Mandle: Reconciliation

“The biggest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution that has to start with each one of us.” In some contexts this quote from Dorothy Day may, at best, come across as trite or, at worst, an impossible directive. However, if these words are taken seriously, or better yet, sincerely, there are few acts one could undertake in this lifetime that would be more profound.

Astoundingly, S. Billie Mandle has not only achieved a revolution of heart, but she has generously chronicled the long trail she blazed to get there in her new book Reconciliation, published by Kehrer Verlag. That said, to fully appreciate the enormity of Mandle’s project, you must match her mindfulness. A deliberate pace and attentive eye is necessary, as nothing can be taken for granted in Reconciliation.

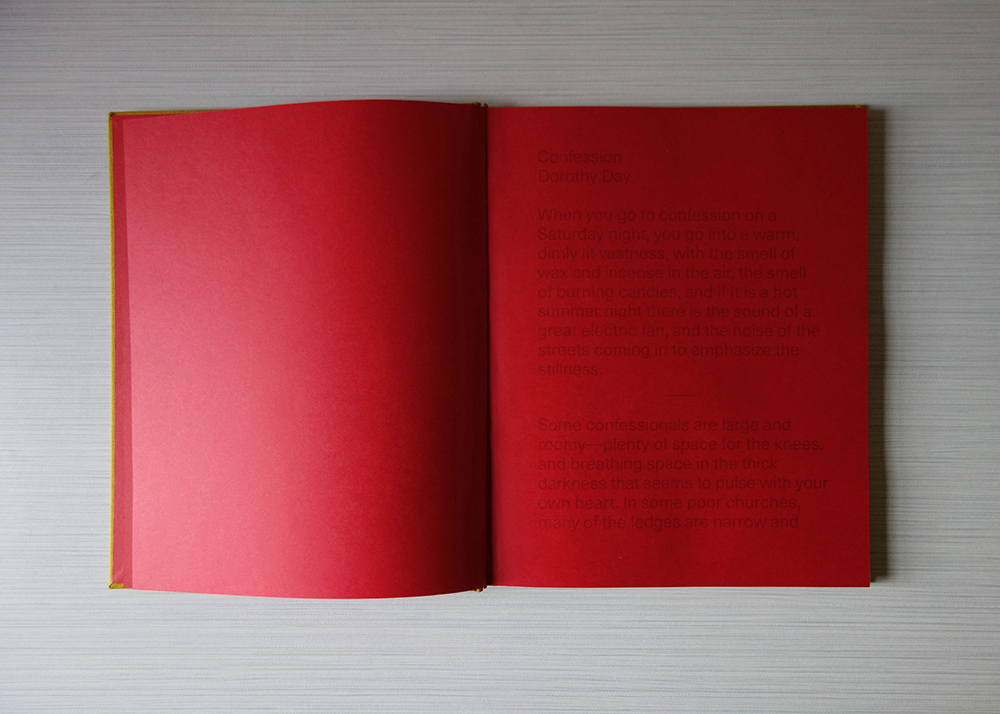

Following this logic, even the title of the book has the potential to convey multiple meanings. The word reconciliation can be defined in at least three different ways. The first definition relates to conflict resolution, as in reconciling differences. The second definition relates to matters of accounting and legislations; records are reconciled to ensure that they are in agreement. And lastly, reconciliation also refers to the Roman Catholic sacrament of penance, also known as confession. Each of these definition definitions holds the potential to prime readers for what they will encounter in the subsequent 104 pages.

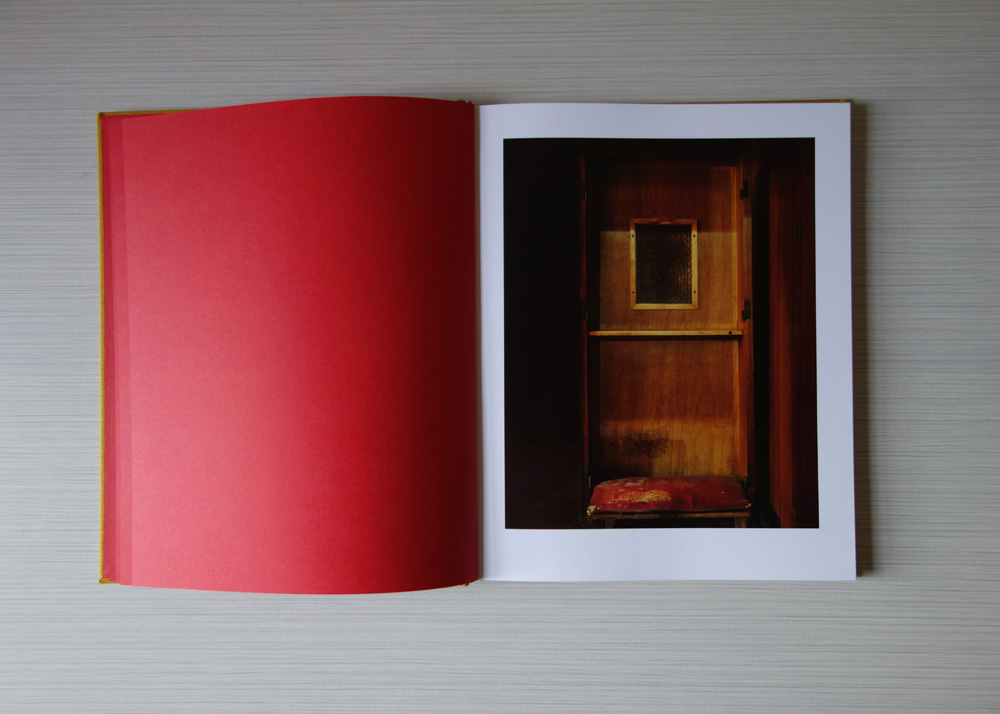

For over ten years Mandle has photographed confessionals in Catholic churches across the United States. Reconciliation collects forty such images, across five chapters, from this long-term pilgrimage. In focusing on the confessional specifically Mandle astutely calls attention to a site that is widely known, but perhaps seen less and less in America in the 21st century. The BBC notes that there are over one billion Catholics worldwide, but just 51 million are in America. And in a recent survey from the Pew Research Center found that in 2007 24% of Americans identified as Catholic, but that number fell to 21% by 2014. Pew also found that 13% of Americans identify as former Catholics.

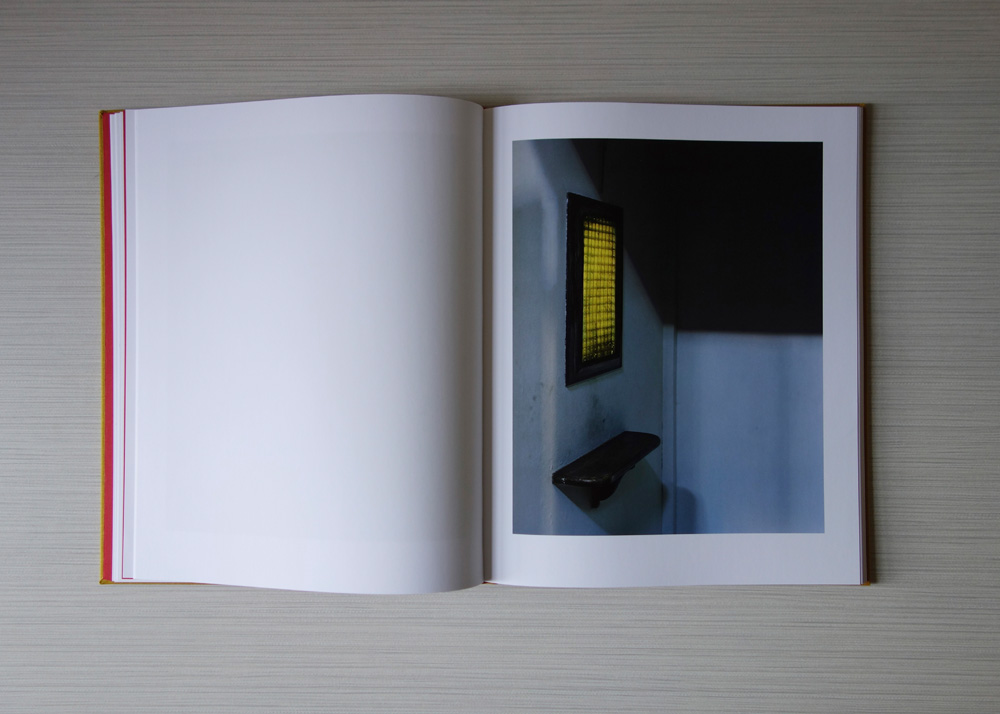

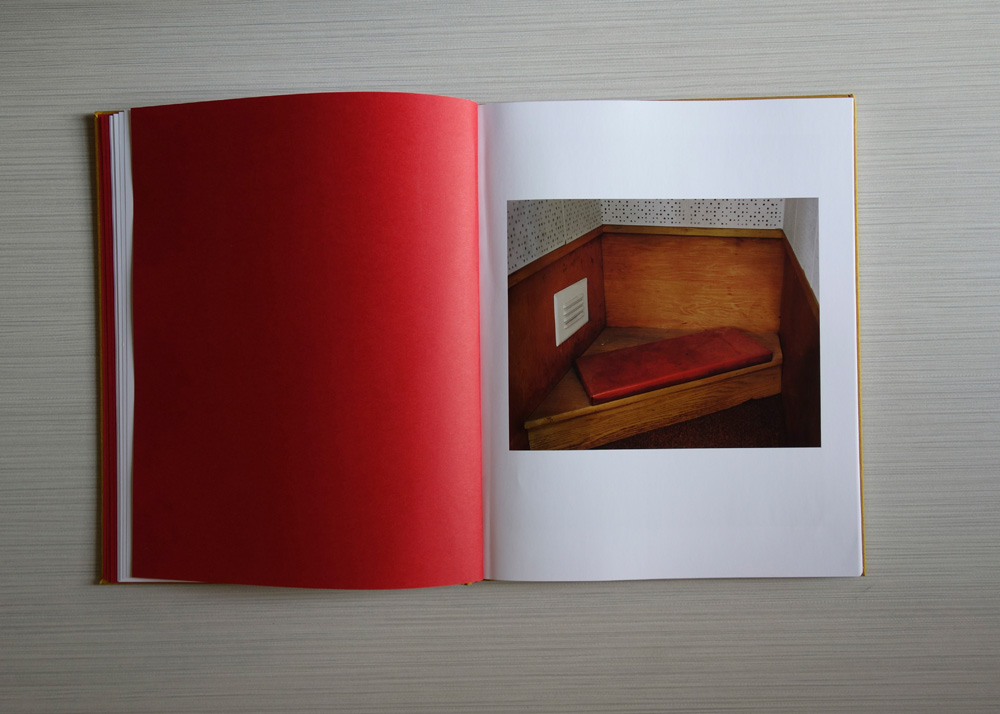

Within the pages of Reconciliation Mandle never ascribes a label to characterize the status of her own beliefs. Perhaps because no existing labels can aptly describe or capture a reconciliatory process that has lasted much longer than ten years. To quote Mandle, “Confessionals hold traces of secrets and sins — traces from each penitent, traces from the Church. Each person seeks redemption surrounded by layers of past confessions. I was raised Catholic and as a queer woman my relationship to the Church is complex.” The accompanying essay in the book by Kirstin Valdez Quade speaks in more explicit terms about an aspect of the complexity Mandle may be referencing, “Forgive me, Father. I’m in love and I don’t think it’s a sin, it doesn’t feel like a sin, it feels like love, like goodness, like every beautiful thing He created.” It is through her images then that Mandle conveys the multifaceted and conflicting emotions that are pent up in the materially minimal, yet metaphorically loaded confessional space.

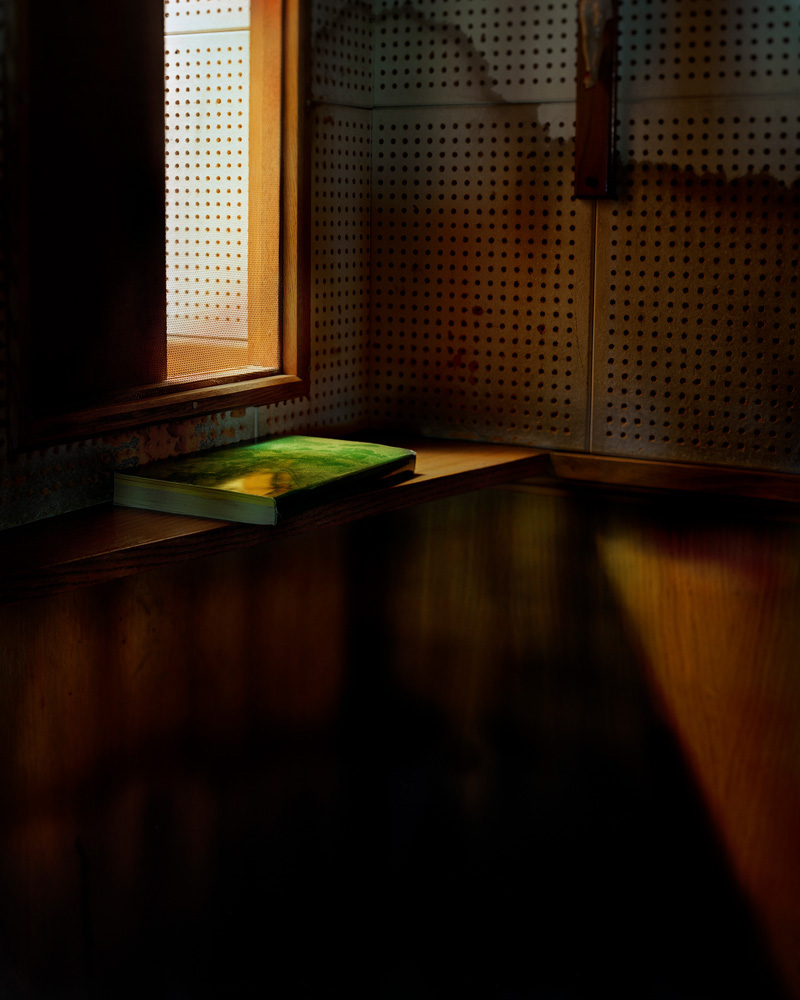

The image “Saint Rocco” exemplifies Mandle’s approach to balancing admiration, or at least fascination, with skepticism. Her surgical framing, sharp focus, and long exposure reveal unexpected and even bizarre details. The confessional walls of Saint Rocco are constructed with a grid of what appears to be pegboard panels that have seen better days. Gray-blue stains drip down a long section of these panels, running parallel with the confessional screen, likely an indication of water damage, mold, or both. But these stains also suggest waves, tears, or relic-like impressions. Similarly, the confessional screen itself, and the ledge below it, suggest some precarity. Both of these crucial elements appear to be fastened into the patchwork of panels with just a handful of delicate hooks. But it is the screen itself, which separates and connects the penitent from the priest, that is the central focus of the image. It appears as a glowing grid within the larger grid, reading much more like a window or portal, bathing this small space in diffuse white light. The screen is almost modernist in design, but it too reads as fragile. Perhaps made of some sort of translucent plastic tile, and echoing the pegboard, the screen is, literally, holey. While the design of this space is certainly improvised and largely practical, the iconography of stigmata is inescapable. Conversely, the pairing of the ledge with the window recall commercial ticket windows and bureaucratic cashiers. Somehow, a kind of institutional and ritual transcendence persists in this fascinating space.

All that said, if I was a member of Saint Rocco church and used this same space for confession every week, I probably wouldn’t think twice about the details I’ve just enumerated. The strangeness that I can remark on from afar, is likely invisible or inconsequential to those seeking a sacrament. Prayer and absolution must carry on and presumably the environment shouldn’t affect this quest. The success of “Saint Rocco” is its ability to signal both devotion and surrealism. Mandle expertly navigates this balancing act in this image, and every image in Reconciliation, with a smoldering quietude.

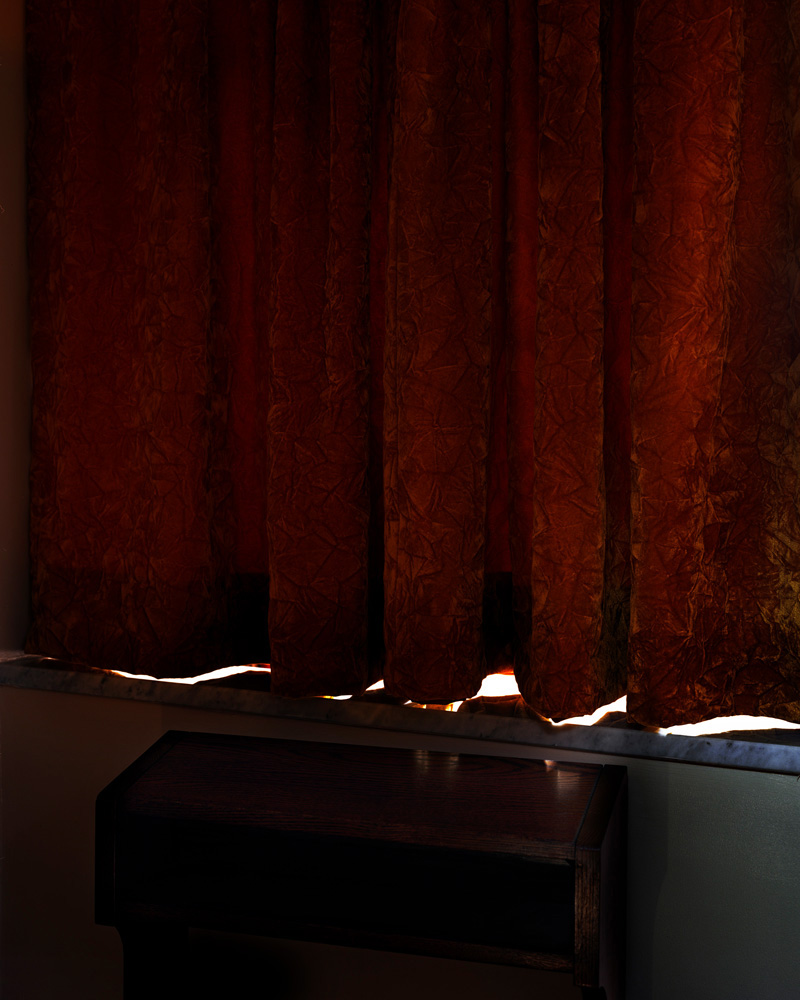

One of Mandle’s goal for Reconciliation was to transform confessionals, “from places of stark binaries into sites that expose contradictions.” Mandle has absolutely achieved this transformation, and yet she also poignantly refrains from any explicit endorsement or rejection of faith. This is also true of the Valdez Quade text that concludes Reconciliation and the text by Dorothy Day that opens the book. Day, who was a Catholic convert and co-founder of the Catholic worker movement, was also a journalist, activist and anarchist. Day apparently never thought these aspects of her life were contradictory and often wrote, “it all goes together.” Perhaps this is a fitting mantra for Mandle’s project as well. Confession through a ticket window; suffering in haunting light; penance from a folding chair; absolution from behind a frayed curtain; disappointment while staring into worn corporate carpet patterns. It all goes together. Mandle’s work to collect and contend with this allness, without clear-cut judgement or tidy conclusions, is profound. Somehow, and in 2020 no less, she has provided a masterclass in conceptual and personal equanimity. Reconciliation is indeed a revolution of the heart, and a book that rewards deep and multiple readings.

For 10 years I photographed the dark interiors of confessionals in Catholic churches around the United States. Confessionals hold traces of secrets and sins — traces from each penitent, traces from the Church. Each person seeks redemption surrounded by layers of past confessions. I was raised Catholic and as a queer woman my relationship to the Church is complex. Photographing with a large format camera and available light, I transformed the confessionals from places of stark binaries into sites that expose contradictions. The photographs are a way of grappling with darkness. – S. Billie Mandle

S. Billie Mandle is an artist based in Los Angeles and Western Massachusetts. Her work has been supported by grants from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the Berkshire Taconic Trust and her images have been featured in publications such as Aperture, Cabinet and Wired. Her monograph Reconciliation was published in summer 2020. She is an Associate Professor of Photography at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. @sbilliemandle

Contributors to RECONCILIATION:

Everything Studio is Jessica Green and Tom Griffiths. Their multidisciplinary design firm in Brooklyn works in all areas of print and interactive design. Projects include Bomb, Cabinet and 4Columns.

Kirstin Valdez Quade is the author of Night at the Fiestas, which won the John Leonard Prize from the National Book Critics Circle, the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a 5 Under 35 award from the National Book Foundation, and was a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Award. It was a New York Times Notable Book and was named a best book of 2015 by the San Francisco Chronicle and the American Library Association. Quade is the recipient of the John Guare Writer’s Fund Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, among other honors. She is an assistant professor in the creative writing department at Princeton University.

Dorothy Day was an American journalist, social activist, Christian anarchist, and Catholic convert who was dedicated to fighting for the poor and the homeless. Day initially lived a bohemian lifestyle before gaining public attention as an activist after her conversion to Catholicism. She was a political radical, perhaps the best-known radical in American Catholic Church history. The Long Loneliness, her memoir, subtitled, “The Autobiography of the Legendary Catholic Social Activist,” is a testament to her life of social activism and her spiritual pilgrimage.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Broad Strokes III: Joan Haseltine: The Girl Who Escaped and Other StoriesMarch 9th, 2024