Portuguese Week: Edgar Martins

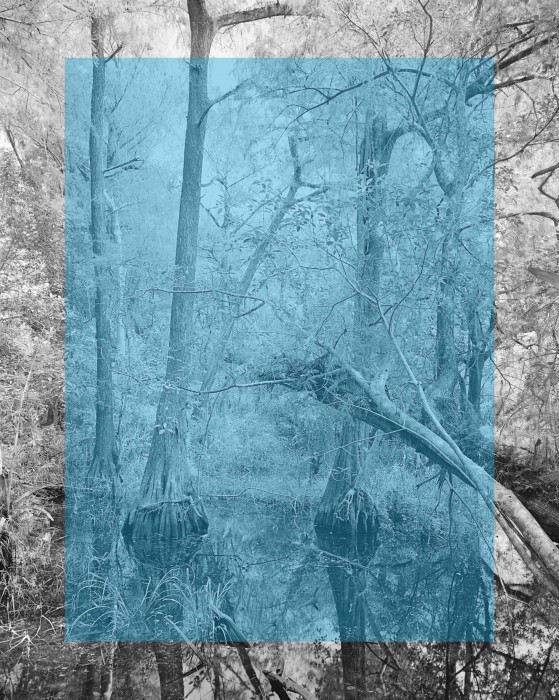

There are few photographers whose work is as intriguing, multifaceted and theoretically dense as Edgar Martins‘. His photographic practice is charged with symbolism, thought and reflection. He dedicates a whole lot of time to the study of photography, its implications as practice, language and, curiously enough, its limitations. For that, over a long and successful career, Edgar has been working on very different themes, such as housing, airports, power stations or the European Space Agency, just no name a few. Things are sometimes what they seem, sometimes not, but most of them they are also a lot more. Edgar inquires into all of the possibilities, or close to it. He was kind enough to share with us his thoughts.

Carlos Barradas: I would like you to introduce yourself and then describe your trajectory, in particular what brought you to photography. Why did you decide to go to the UK in the first place?

Edgar Martins: My first passion was the written word as I was studying Literature and Philosophy in Macau in the late 90s. At the age of 18 I wrote and self-published a book of poetry and essays. It was structured as a bio-poetic novel, organized in 3 distinct chapters: poetry, poetic prose and philosophical essays. I’m still fond of the title: Mãe, Deixa-Me Fazer o Pino (Mum, Let Me Do The Handstand). This book was very much inspired on beat poetry and on the existentialist de-ambulations of Fernando Pessoa, particularly The Book of Disquiet. I realized when I finished it that so much of my writing was incredibly visual. This prompted my exploration of visual arts and photography in particular. That’s the main reason I came to the UK. To study visual arts and photography. The decision was also made easy by the fact that I spent a great deal of time in Hong Kong in the 90s and so had a lot of British friends. In fact my closest friends in 96, when I came to the UK, were all English speaking. Above and beyond that I was totally immersed in English culture and in particular English music so the appeal of England to me was very much tied into this.

CB: You once said that photography is like a language. Do you believe in a virtual infinite progression and evolution or might we arrive at a point of regressing?

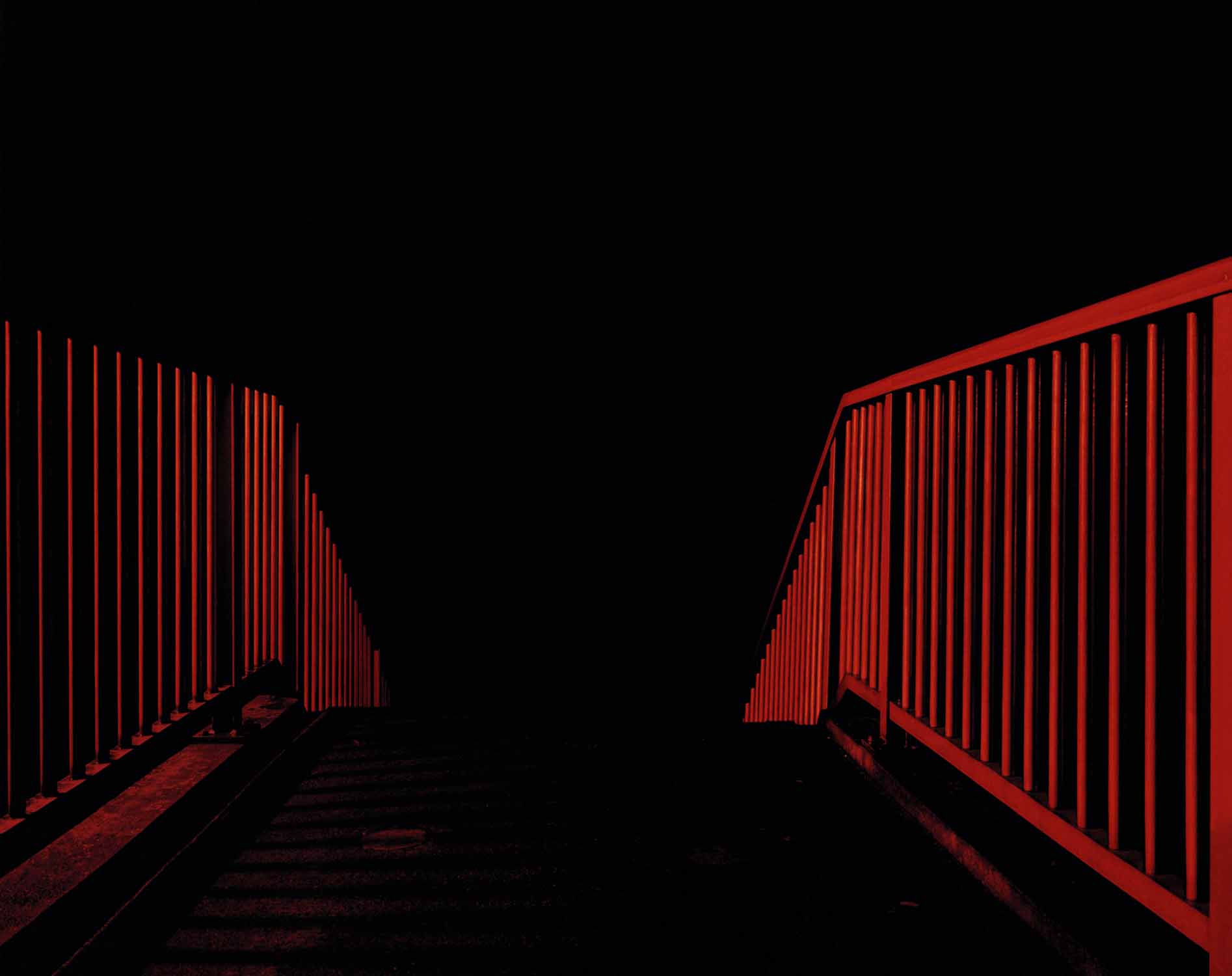

EM: I’ve always had a particularly recalcitrant relationship with photography. When I started I was excited by photography’s ability to document the world in excess detail, it’s technicality and its documentary potential captured me. Paradoxically, what motivates me now are its failings, it’s insufficiencies. I’m interested in figuring out what it means for the medium when it’s no longer a mnemonic or recording keeping device, a gateway to the sublime. I’m interested in seeking answers to questions such as: What is left when photography is no longer a shutter based art of time or a lens based art of space? How do we, as visual practitioners, address the politics of visibility in an era that privileges transparency yet is skeptical of fact? I think some of these ideas bear great significance for contemporary photographic practices and for the documentary forms.

The media landscape has changed dramatically with technology, social media, the internet, digital photography. I have grown increasingly convinced of the fact that Photography has reached a singularity of sorts. Image making has become inextricably aligned to Technocapitalist doctrine: it is all about constant upgrading & optimization (the latest lens, the latest camera, the latest app, the latest operating system), to the detriment of the creative process. I believe this has been responsible for steadily exacerbating a well know neurological phenomenon that occurs with abundance of choice: when people are overwhelmed by choice, they choose nothing in the end. For better or worse, this pandemic has introduced circumstantial constrains to our decision-making. It has shown artists and photographers they don’t need the latest gear to create. Although I have only ever worked with one (analogue) camera and lens, I have embraced these constrains nonetheless and used them to redefine my relationship with the medium.

Photography is ubiquitous. Professional photography has an increasingly difficult role because of the rise of amateur photography and social media platforms, which are challenging the role of the professional as the purveyor of truth and visual content. But I do not believe the influence of amateur photography is necessarily a bad thing. In fact I welcome it. I no longer trust the agency of the professional photographer.

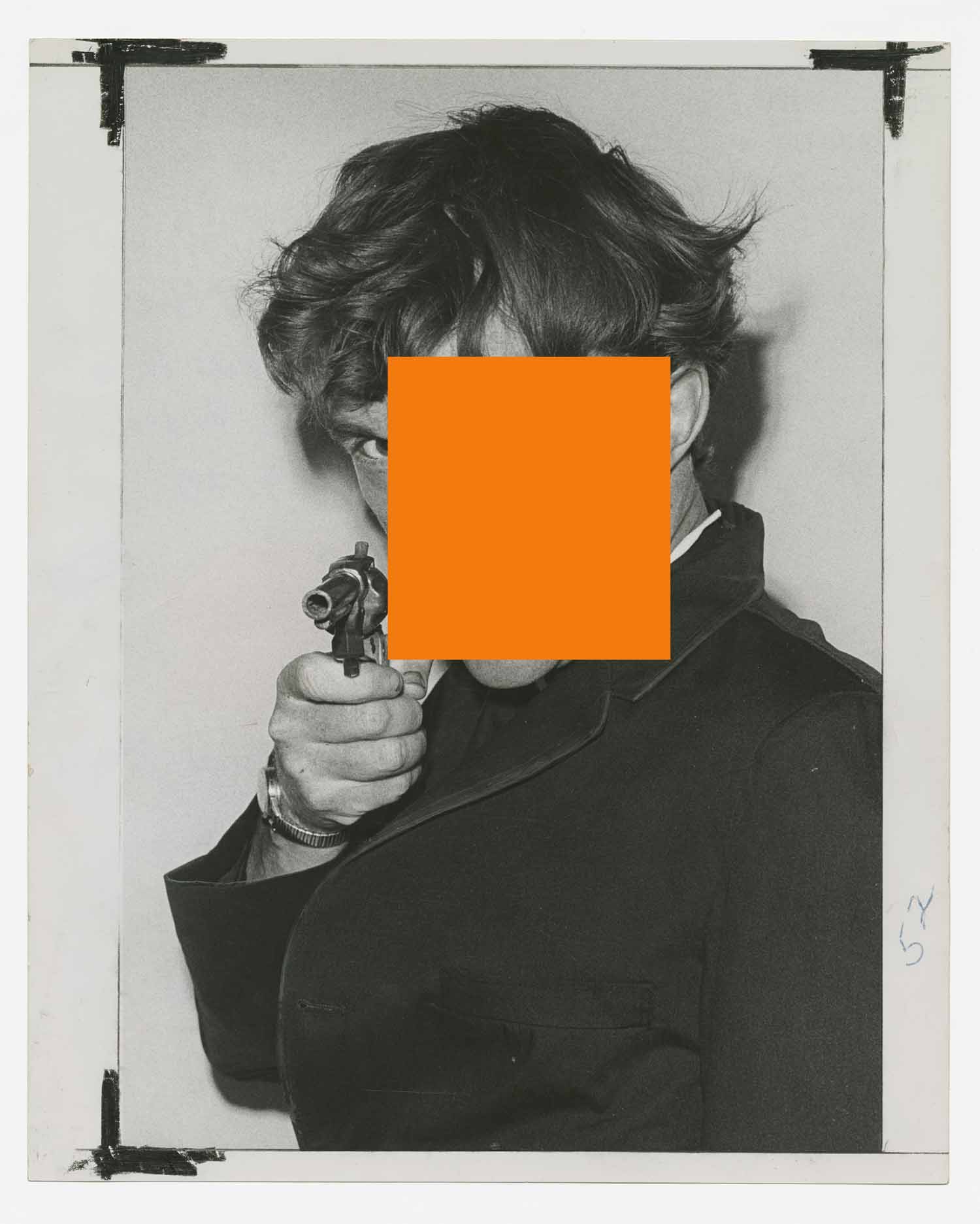

Take the example of war photography. I have never held a great deal of faith in photography’s powers of testimony in these ethically charged contexts, particularly by professional photojournalists. Photographs of horror, violence and trauma raise a disconcerting paradox: they contribute to intensifying a traumatic awareness of death, but at the same time have a pacifying effect, allowing for a distanced and cold discernment that inevitably alleviates the extent of the trauma. The image, I believe, protects us from tragic reality. However, I have come to believe that there is a place for photography in these kinds of environments.

The point at issue is what role should it play and how should it operate? How do we represent and communicate “unimaginable” tragedy? How can photographs reveal and resist at the same time? I believe that photographs of horror and violence should be unvarnished, unaesthetic, unpolished. I believe that all photographs taken in conflict and war settings should be a zero sum game, produced by those that have everything to lose and nothing to gain. I believe in photographs as an act of resistance. I believe in the agency of the citizen, the agency of the oppressed, the agency of the freedom fighter. I do not believe, however, in the agency of the professional photojournalist or news organization.

CB: Your work is particularly methodical, but is it also like this when you choose the subject matter? Does chance appear in your work and comment on the answer.

EM: I always start out with a goal but never an end point. So I never know for sure how a project will pan out. Especially these days that I’m working in a rather more multidisciplinary fashion and with a much more hybrid understanding of photography. But the short answer to your question is that I welcome chance and all the side roads that my research and projects take me down. Photography for long as been defined about control, whether its the control the medium exerts over any particular occasion or circumstance or the control that the photographer has over its subject. In much of my work (and despite appearances) I’ve often deliberately sought to relinquishing a certain element of control. At the same time photography has also long been defined by a relationship with the subject it purports to represent. That is why I’m so interested in the question of what it means for photography if it does not identify with its subject but its absence? Can absence be a form of activation? This is the central theme of many of my recent projects.

CB: I imagine your approach to the methodologies depends on the project, but your definition of a photographer has a really wide scope, I believe?

EM: I think we are all photographers to some extent. We have all become very discerning viewers and image consumers. So I’m less interested in what it means to be a photographer than what it means to look at a photograph.

CB: Technology, surfaces, topographies, death, incarceration. Do you consider your work to be in a constant evolution or are they ramifications of interests?

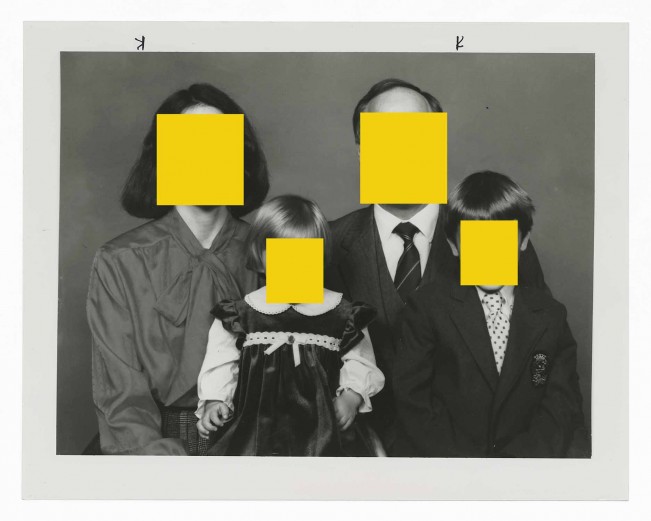

EM: There is definitely an evolution. Each project influences the next to some extent. For example in the project I launched last year titled What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase I worked with its inmates and their families and used the social context of incarceration as a starting point to I explore the philosophical concept of absence, and address a broader consideration of the status of the photograph when questions of visibility, ethics, aesthetics and documentation intersect.

My work deliberates on the themes of incarceration and trauma without physically portraying the subject it represents (I went to great lengths to avoid shooting inside the prison or its inmates).

In the current project I am working on right now, I am further exploring the relationship between photography, trauma and absence. It comprises a collaboration with the Archive of Modern Conflict and various NGOS to examine the death and disappearance of my good friend and South African photojournalist Anton Hammerl during the Libyan war in 2011. This project will lead to new work that examines the paradoxical role that photography has played in conflict zones. My goal is to develop a visual lexicon that can be used as a representational & pedagogic tool to interrogate & document conflict as well as the spectacle of photojournalism. But at the heart of this project lies this question: how to you document a subject that eludes visualization, that is absent or hidden from view? What does it mean to witness an event? What does it mean to document an event without witness?

CB: Your use of metaphors is immensely strong, does that come from your previous wish to be a philosopher?

EM: I’m not sure. I don’t even know that I’m interested in metaphor per se. I’m certainly interested in exploring the concept of Photography as catachresis (a term originally proposed by the Art Historian Richard Schiff – though my exploration of this theme is rather different from Schiff’s). For example in What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase I employed a lot of imagery of animals. They are often understood by viewers as metaphors for psychological states. However, I actually used them to explore the idea of Photography as catachresis. Let me give you a quick example of a catachresis: ‘the arm of a chair’ or ‘the leg of a table’. These terms are catachrestic because they use symbols related to human physiology to describe something where there is no other way to say it. So a catachresis is a trope that registers at the same time language’s ability to respond to something when under pressure but also its own inadequacy. I feel the same way about the role of photography in ethically charged environments (prisons, legal medicine institutes, etc.)

CB: Is there anything as Portuguese photography?

EM: I’m not sure. I don’t think so.

CB: What next?

EM: I’m working on a touring exhibition of What Photography & Incarceration have in Common with an Empty Vase, which will open at The Herbert Museum & Art Gallery in Coventry from 15 Jan – 18 April 2021, followed by the Geneva Photography Centre (June-July 2021), MOCA London (Fall 2021) and MNAC Lisbon (Fall 2021). But my priority right now is to research and complete the project I have described above about the death and disappearance of my good friend in Libya in 2011.

Edgar Martins was born in Évora (1977) (Portugal) but grew up in Macau (China), where he studied Philosophy and where he published his first novel entitled “Mãe deixa-me fazer o pino”. He studied for a BA (Hons) at the University of the Arts (London) and an MA in Photography and Fine Art at the Royal College of Art (London). His work is represented internationally in several high-profile collections, such as those of the V&A (London), the National Media Museum (Bradford, UK), RIBA (London), the Dallas Museum of Art (USA); The Calouste Gulbenkian Museum/Modern Art Centre (Lisbon), MAAT/EDP Foundation (Lisbon), Fondation Carmignac (Paris), MAST (Italy), amongst others. His first book—Black Holes & Other Inconsistencies—was awarded the Thames & Hudson & RCA Society Book Art Prize. A selection of images from this book was also awarded The Jerwood Photography Award in 2003. Between 2002 and 2018 Martins published 15 separate monographs, which were also received with critical acclaim. These works were exhibited internationally at institutions such as PS1 MoMA (New York), MOPA (San Diego, USA), MACRO (Rome), Laumeier Sculpture Park (St. Louis, USA), Centro Cultural de Belém (Lisbon), Centro de Arte Moderna de Bragança (Portugal), Centro International de Arte José de Guimarães (Portugal), Museu do Oriente (Lisbon), Centro de Arte Moderna (Lisbon), MAAT (Lisbon), Centro Cultural Hélio Oiticica (Rio de Janeiro), The New Art Gallery Walsall (Walsall, UK), PM Gallery & House (London), The Gallery of Photography (Dublin), Ffotogallery (Penarth, Wales),The Wolverhampton Art Gallery & Museum (UK), Open Eye Gallery (Liverpool), amongst many others. In 2010 the Centre Culturel Calouste Gulbenkian (Paris) hosted Edgar Martins’ first retrospective exhibition. Edgar Martins was the recipient of the inaugural New York Photography Award (Fine Art category, May 2008), the BES Photo Prize (Portugal, 2009), the SONY World Photography Award (Landscape cat. 2009; Still-Life cat 2018; Architecture cat., 2018), the Int. Photography Awards 2010 (Abstract category), etc. He was nominated for the Prix Pictet 2009.

He was selected to represent Macau (China) at the 54th Venice Biennale.

Follow him on Instagram: @edgarmartinsphotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026