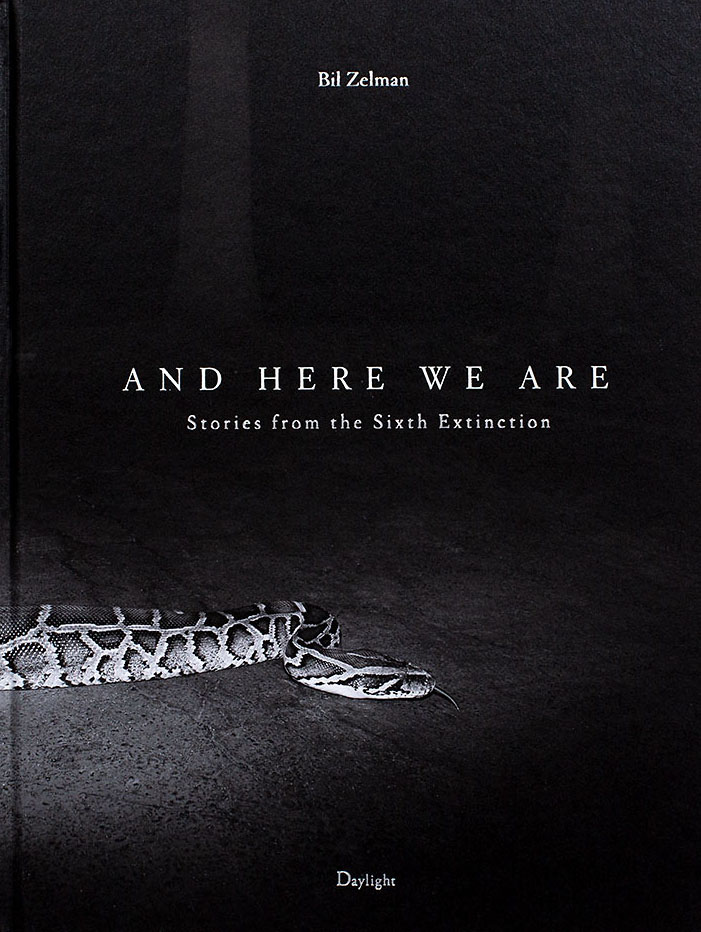

Bil Zelman: Here We Are, Stories from the Sixth Extinction

Many photography projects address human-caused devastation in a way that doesn’t quite evoke the horror nor the reality of the situation. It seems as if many photographers approach the topic with the same sense of awe for the natural world that is inherent in traditional landscape and wildlife photography. However, the work often falls short of evoking a call to action as the viewer gets lost in the beautiful light, the impeccable composition, the colors of schools of fish frantically swimming beneath the sea, or the perfect moment a polar bear jumps from ice sheet to ice sheet.

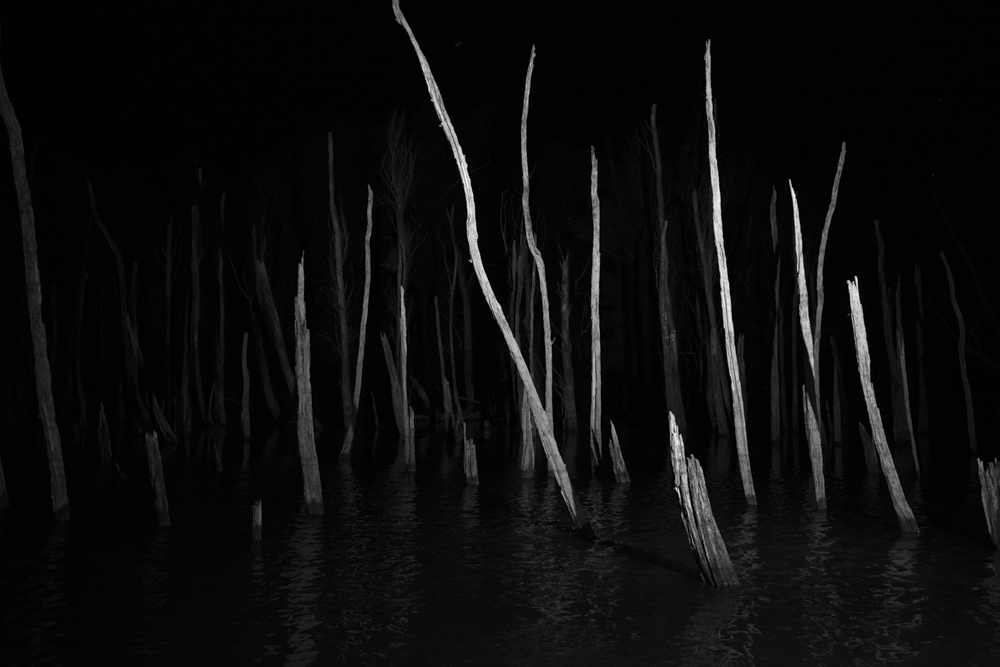

Then there is photographer Bil Zelman and his raw interpretation of the planet in his most recent book Here We Are, Stories from the Sixth Extinction, published by Daylight Books. Zelman’s black and white photographs lit by strobes at night in the muck of everglade swamps, western El Niño storms, and the desolation of barren trees from California wildfires harkens the viewer to see, process, and then respond. We are in the beginnings of the sixth extinction, and it is dire.

Bil Zelman relentlessly explores the spirit and psychology of his work. Sought after for his highly expressive portraits and lifestyle photography, Zelman creates a completely immersive environment for his subjects to engage with. His commitment to capture real moments with genuine emotions is seen throughout his eclectic range of work, from editorial stories to commercial campaigns.His work was included in Archive’s Top 200 Photographers Worldwide for the past 15 years, earned the ICP Lucie Award for “Deeper perspectives” and printed on the cover of The Commercial Arts Photo Annual.

Zelman is also seasoned advertising director, working on campaigns with a diverse range of clients and published multiple fine art monographs.

Polly Gailard: Your lifestyle and portrait work is a very eclectic collection of seemingly shared moments complemented by movement, light, and emotion. It’s as if the viewer is invited to join a circle of friends that gather in fun places and have exciting lives, each frame energized by the human spirit. How did it feel to depart with that style of shooting into a solitary way of working burdened by slogging equipment into the wilderness to explore the atrocities of climate change at night? Your commercial-style so free and spontaneous, your “And Here We Are” style so specific and intentional. How did you process this new way of seeing?

Bil Zelman: This work is so removed from my lifestyle work that I don’t compare the two.

The work in this book started in the Amazon where I was photographing a bird migration that had appeared about one month early, along with some invasive species, but I was having difficulty isolating the issues or species I wanted to highlight. Over a period of about six months I watched the world I thought I knew melt away as I researched and studied anthropogenic issue over issue. (Negative Human effects). For me to tell these stories with photographs (as limiting as photographs are) it became necessary to find a way to visualize one slice of a landscape and not the whole. The solution ended up being powerful strobes at night.

PG: Can you discuss the reasoning behind selecting nighttime as the backdrop for the series? And how using strobes in the wilderness became essential to the project? Furthermore, how do you feel that the black and white images intensified your investigation into the changing landscape instead of color?

BZ: Each of these images illustrates an anthropogenic issue of one sort or another and I present them as evidence. I reference Weegee’s hard flash black and white murder scenes from the 40’s because many of these images are exactly that. I’m also drawn to the metaphor that these species are threat naïve to the rapidly changing world around them and existing alone in the darkness. The lighting is uncomfortable and as frightening as the issues at hand.

PG: How long did the project take from inception to book publication? Did you receive grant funding other than a Kickstarter campaign?

BZ: I managed to raise over twenty thousand dollars on Kickstarter but I flew over 60,000 miles and spent about eighty thousand on the project over a period of three years. I knew I would never break even and I’m wildly passionate about the subjects and conservation as a whole so I chose to ignore the price-tag.

There are lots of grants I could have applied for and I started on a Guggenheim but grant writing is a full-time job in itself so I just shot commercially during the day and worked on the book at night.

PG: I imagine there was quite a bit of waiting in the night – waiting for the python to show up, waiting for the alligators to gnash their teeth. Can you talk about the physical challenges you encountered during your fieldwork? Did you have any help?

BZ: Some of the shooting happened in easy places but yes, overall it was a challenging task and I was lugging studio sized power packs and light stands into some remote places.

I have a very good friend who joined me on three trips and helped tremendously. (Poor guy took a three-pronged treble hook deep into his leg while helping me pull up invasive zebra mussels) He and my wife both helped with the gear several times but most of the time it was just me, a headlamp and a backpack on my front and back walking through the dark.

I was stung about 45 times on one ankle shooting the bees and reckless enough to get within about six feet of those alligators but the most dangerous shot was of the lone Douglas Fir tree. The trunks of those trees are 20 feet in diameter and the stumps 6-10 feet tall. It was raining and my friend and I would slide down one and either hit ground or disappear into enormous piles of branches hoping not to get one in the neck.

We only managed to capture three frames before the rain stopped my radio transmitter from firing the flash and leaving in pitch black and the rain wasn’t that much fun.

I’m also eternally grateful to other friends that helped along the way and the dozens of scientists and conservationists who contributed their time and knowledge.

PG: The New Republic published an article about you and the book where you described becoming depressed during the making of the project and you became “Sad as hell”. If that was the case, what made you continue? Did you find satisfaction once the project was complete.

BZ: I see the world very differently now. When I’m in a park near my home in San Diego I quietly note that every tree I see was imported and non-native and growing because we diverted water from the Colorado river. (Which no longer reaches the Gulf of Mexico). When I flew over the Mississippi for work last month I thought about the fact that invasive Asian Carp will likely become the predominant freshwater fish in the United States once they break through the electric fences keeping them out of the Great Lakes. And I promise you it will happen in my lifetime. We’ve already converted 42% of Earth’s terrain to agriculture even if you don’t see it on your drive to work each day.

Extinctions are extremely rare occurrences and what we refer to as “mass extinctions” have only happened five times in 3.5 BILLION years- And inside of my lifetime, we have started the sixth which is mind-numbing.

So, yes, spending thousands of hours reading, photographing, and writing about these dark issues affected me.

PG: In the same article, you mentioned that “And Here We Are” isn’t a work of advocacy. If not, how do you want the viewer to respond? What then exactly should we take from this very dark and serious subject matter?

BZ: I feel the environment and state of the planet as a whole isn’t something that can be advocated for in one small book but that’s a nuanced perspective. My only solution isn’t something people talk about. We can’t unscramble the egg and playing whack-a-mole with environmental issues isn’t something humans are intelligent enough to calculate.

The problem, of course, is that there is a plague of humans. It took 250,000 years to reach one billion humans but only one hundred more to reach 7.6 billion. These myriad problems are not going to be solved because you take shorter showers and recycle your toothbrush.

No politician is going to get elected with a platform where they tell people they can’t have children and lifespans are still increasing so I’m in no way hopeful for significant, positive changes. Devoting as much of the planet we can to permanent wild lands as E. O. Wilson prescribes in his book Half-Earth is a great start. I wish I had a call to arms that wasn’t as dark as humans somehow disappearing altogether but I don’t. Perhaps it will make people more mindful of how many children they have and to vote responsibly but that’s asking a lot as well.

PG: Can you offer any advice to other photographers pursuing personal projects without significant funding?

BZ: Foremost you have to be very passionate about something and learn and explore it inside and out. Now that anyone can take a picture, good photography is about ideas, perspective and nuanced communication.

As for funding there are grants as you mentioned before but photography doesn’t have to be expensive. Mine was because my obsession led me to fly all the way to the equator and back in 48 hours to take one photo of insect diversity- Along with 53 other such adventures.

PG: Will you continue your exploration into our changing climate by taking the project to other countries? And do you plan on sharing the work outside of the book?

BZ: Absolutely! I had a huge solo show in Italy 2020 that was understandably cancelled.

I’m a board member and huge supporter of American Photographic Artists, and they helped secure a theater at the Museum of Photographic Arts where this work was first shown. In the end the ticket money was all donated to charity and I hope this work could be a part of more philanthropic and educational programs in that model.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026