Brian Ulrich: The States Project: Rhode Island

This week The States Project focuses on Rhode Island, a small but mighty bastion of photography, home to a host of significant photographers and well regarded institutions. Our penultimate States Project is curated by photographer Brian Ulrich, a major force in American story telling. Today, we showcase his photographic efforts featuring two projects on American consumption, Copia and The Centurion. An interview with Brian follows.

Brian Ulrich’s photographs portraying contemporary consumer culture are held by major museums and private collections such as The Art Institute of Chicago; Baltimore Museum of Art; The Cleveland Museum of Art; Eastman Museum; The J. Paul Getty Museum; Milwaukee Art Museum; Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego; Museum of Contemporary Photography; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the North Carolina Museum of Art; the Margulies Collection; the Bidwell Collection; and the Pilara Foundation Collection. Ulrich has had solo exhibitions at the Eastman Museum; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the North Carolina Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego; as well as numerous group exhibitions such as the Museum of Modern Art; Pier 24; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Walker Art Center; the Museum of Contemporary Photography; the San Diego Museum of Art; the Haifa Museum of Art; the New York Public Library; the Carnegie Museum and the Aperture Foundation.

In 2009, Ulrich was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. His first major monograph, Is This Place Great or What (2011) was published by Aperture, and was included in The Photobook: A History Volume 3 (2014). The Anderson Gallery published the catalog Closeout: Retail, Relics and Ephemera (2013). His forthcoming publication, The Centurion (2019) will be published by FW: Books.

He is currently an Associate Professor and the Department Head of Photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. IG: @brian_ulrich

Copia and The Centurion

Since 2001, I have been engaged with a long-term photographic examination of the peculiarities and complexities of the consumer-dominated culture in which we live. This project titled Copia, explores not only the everyday activities of shopping, but the economic, cultural, social, and political implications of commercialism and the roles we play in self-destruction, over-consumption, and as targets of marketing and advertising.

The communal sense of grieving, healing and solidarity that broke down social walls as our nation grappled to make some sense of the tragedy of September 11th was quickly outpaced as the President encouraged citizens to take to the malls to boost the U.S. economy thereby equating consumerism with patriotism. The Copia project began as a simple curiosity; were people out shopping to follow a patriotic directive? It quickly dawned on me that the subject I began to explore was something a lot bigger: one historical, anthropological, ideological and indicative of American identity and psychology.

So many of the ideas set forth in the 20th century—the American ideal, the manufacture of desire, the insistence on exponential growth—all brought us to a point where the measure of the quality of our lives is based on how much we spend and how much time we have for leisure. Once we began to equate this well being with financial markets our futures were gambled. The financial market does as it is built to do, rise and fall, gain and recede, but with so much of our well being invested in it, we act surprised when the tides shift.

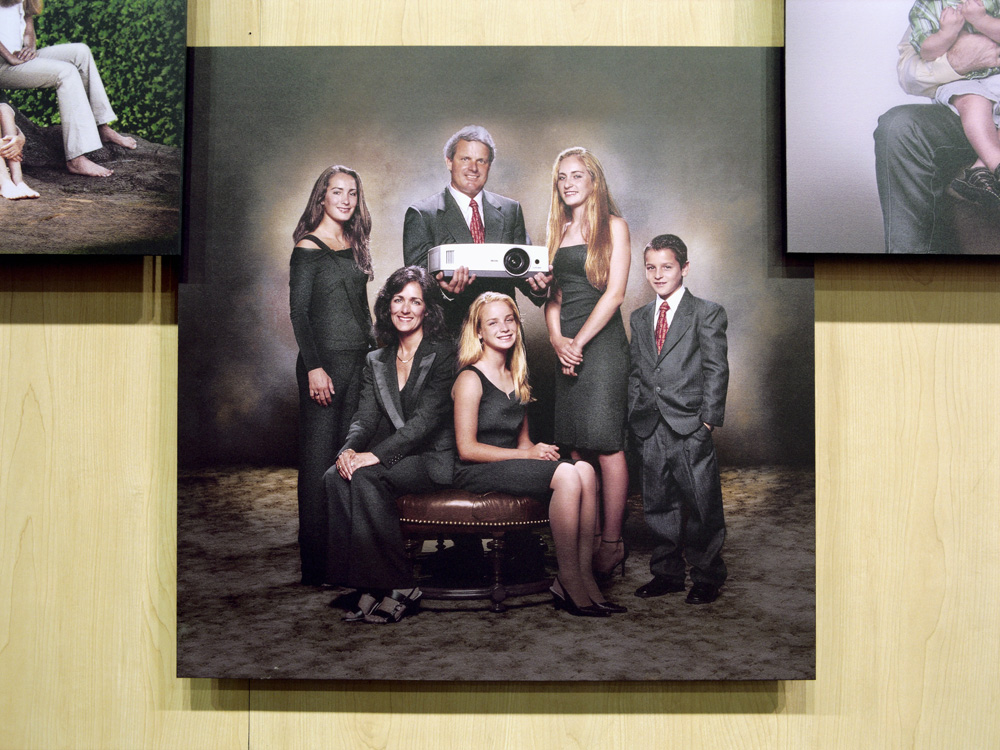

For the past five years I have been making photographs that explore growing economic disparity and the resulting social, economic, and psychological effects of when luxury or wealth becomes the preeminent definition of success in culture. The Centurion is named for the moniker of the famed American Express Black Card, which was created in response to persistent urban legends and stubborn rumors of its existence throughout the 1980s. This contemporary tale of the rendering of reality from urban myth is perhaps emblematic of a new Gilded Age – where illusion manifests itself as power through wealth.

Photography holds a particular power to reveal that which many in our culture are blind to, especially within the culture of privilege. Now, it is especially urgent to unpack the myths that drive the widening economic gap and the alluring creation of desire through the seduction of commerce.

-Brian Ulrich

Your work takes you all over the country; does living in Rhode Island shape your work in any way?

Rhode Island serves as a bit of an enclave. For the most part it is the place I return to reflect, edit, and review work made out in the world. I find a lot of our students work like this as well. Only a few are directly inspired by the RI landscape; most produce work on travels and trips, more so than locally. Moving here, I was struck by how inconsistent the light is, you can’t count on the weather and when the light is prominent it’s soft and stretches out at the end of the day into a dim and slow flicker. In contrast when I travel to LA to photograph, the light is beaming up from the sidewalks – begging for pictures. Needless to say, it’s taken some time to adjust to producing images in RI, and just this year I’ve begun to photograph in Woonsocket, a small city originally populated by French Canadians. This place wears its history on its surface, a lot like another project I’ve been working on in and around Petersburg, VA. My approach in Woonsocket is similar: exploration mixed with historical and field research. There is simply not enough work yet to distill my interests here though.

How did you go about finding photographers for this week?

RI is small! There are only so many practicing photographers here. I do think it is no coincidence that all are from academic environments which speaks to my own connection to the prominent and local academic community. I am very lucky to call Steve Smith and Odette England my colleagues at RISD. Theresa Ganz and I met when I first moved to RI and for some time we hosted a critique group.

I’ve always been fascinated with your work, what got you interested our compulsion to shop?

I initially came to this subject through a simple curiosity. In the post 9-11 days I was compelled to try and photograph people coming together in a national grieving process. Strangers were connected in these powerful, emotional ways and I was trying to photograph this candidly, on the streets in Chicago and NYC. I struggled with how to make these pictures – I wasn’t an adept street photographer. About the time I began making some successful pictures, the messaging from the then President was to ask people to come together and spend: ‘we’re calling on the nation’s best shoppers’. I was shocked at the transparency of this, equating nationalism with consumerism and so at the outset I wanted to see if people were heeding the call and actually out ‘patriotic shopping’. I answered that question quickly but then realized that what I was looking at was something a lot bigger and the consequence of a longer economic trajectory.

I feel like your early work was a was a preview to the fall of Rome or something out of science fiction where scientists return to empty monoliths devoted to consumerism. Did you have any of those thoughts when making the work?

It dawned on me especially back in 2003, that what I was looking at was a very specific moment – the dawn of the 21st Century – where things were entering into a period of rapid flux. This historical moment reminded me of the changes at the end of the 19th century and the French artists who responded to that. Manet, Caillebotte and even Atget saw a Paris transformed into a modern capital based on commerce. It wasn’t a far cry then to see Costco as the new downtown, with shoppers leisurely strolling indoors under the hum of florescent lighting much like their century old Parisian counterparts. These revelations guided the work and demanded I build a comprehensive project, so Retail led to Thrift. By 2005 I had an inkling that the economic growth model would burst. It would take a few more years, but in 2008 we saw things start to unravel. In many ways the receding of all the consumer growth economy affirmed many of the ideas I had all along.

Your new project, The Centurion, is incredibly timely as we teeter on the brink of, what I have recently read, one of the worst recessions in history. In a time where everything seems to be falling apart, our planet is in peril, this project explores “the growing economic disparity and the resulting social, economic, and psychological effects of when luxury or wealth becomes the preeminent definition of success in culture.” Can you speak to what you’ve discovered making this work?

If this disparity continues, we will eradicate the middle class in the US. With economic class being such a powerful force in our society; many people look to wealth to define themselves. This isn’t simply an inflation of what people can attain through consumer means but an attempt to define oneself within the pantheons of upper class to attain the very lifestyle that affords power, privacy, security and well-being. Wealth and luxury is not as easily defined as indicators of other economic classes – they function like a shape shifter, constantly redefined, refined – I came across that early on and adapted my photographs to take on new forms such as the abstractions of the store display windows.

After spending time making portraits of people I met on the street I can’t necessarily believe in these memes that “money doesn’t buy happiness” – instead, what does a person look like whose struggle is not for survival? I attempted to translate that into a portrait – that lightness of being. To counter that perception of contentment, while doing research on real estate I came across a seemingly new boon of private homes built to resemble castles. I began to reach out to these castle owners and photographed some of the homes, many of which didn’t seem to simply be constructed as an embodiment of fantasy but also as a return to architecture as defense. By 2015 that sense of fortification was abundant and rather than seek access, it made more sense to photograph from the outside: how the majority of us see such wealth, peering in from the exteriors.

I had a student who stood on the corner of Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills and photographed wealthy women in cars, many who had just had a fresh round of injections. In seeing the work, I realized there are whole swaths of the privileged population that never get photographed. Did you have any push back when approaching your subjects?

I had trips that went well and others that didn’t. On one trip to Los Angeles, I was trying to photograph a landmark house called the Spadena House. It’s the thing tour buses are pulling up to several times a day. I had set up with the 8×10 camera one night and the owner came out just livid. I couldn’t reason with him. He was upset that I was using such a professional camera (the other cameras were fine) and claimed to own the copyright on the home itself. So, in his eyes, I was there to steal something from him. That whole trip people seemed more suspicious, and I was followed or questioned by security, etc. I was trying to get a grasp on this while hearing on the radio that the market had taken a turn for the worse and people were beginning to worry about another 2008. It’s pure speculation on my part, but with that much wealth connected to a volatile market one could perhaps understand that the market would shape behavior and psyche, and, perhaps, induce paranoia.

Lauren Greenfield’s project, Generation Wealth, touches on some of the same themes, looking at the expansive pervasiveness of the culture of wealth all over the world–do you want to expand your project beyond our shores?

I saw Lauren’s show at the ICP and was moved by it. I see hers being about the status and sensationalism that money attracts. I think there’s a reason why there are so few photographic projects about wealth, and Lauren provides us, in some cases, with access to those obsessed by the relationship between money and power. Many of her subjects are privileged to be able to successfully protect their image.

I’ve been interested in how an elite class effects the culture at large, and specifically how in America this period of flux and is largely evidenced by economic forces. Monetary power is central to US history; it is at times so transparent and at other times we are conditioned to be blind to it. So much of the 20th century narrative was to create a nation driven by emotional, irrational forces – there is so much here we need to see, and I believe that seeing can transform people.

More specifically to your question, I attempted some of the Centurion photographs in Europe but to no avail. To be honest, I know I don’t understand nearly as much as I’d like outside of US culture. I feel like I would need to spend such a significant amount of time in another country before I could make the connections that I’m making here in the US.

Does making this work make you question your own consumption?

I photographed almost all the work in the Centurion with the 8×10 camera, so each exposure was an investment of about $30. There were times when I knew it would be months before I would have the funds to get the film processed. As artists we’re often taught to think our ideas are separate from the economics and privilege of making them – I wanted to be hyper aware of the relationship between taking risks and the cost of them. In general one’s mindset can become attuned to the relationships between need, desire and consumption but you don’t have to define success in this way – though this isn’t easy in 21st Century America. Two years ago we bought a home for our family and I had anxiety for months about the problematic nature of home ownership. I’m keenly aware we don’t own anything but that a bank gives us permission to live here. Our society is constructed so that it is increasingly difficult not to participate in consumption.

What’s next?

The Centurion will be published by FW: Books.

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Shane Rocheleau, Jaclyn Brown and I have been making photographs in and around Petersburg, VA entitled, A Glorious Victory. We still have more to do there but hope it will see exhibition/publication soon. After that I am not that calculated; honestly, I expect a major event to happen which will inevitably beg my attention.

What’s the worst advice you ever been given?

You should try the 8×10 camera (best and worst advice).

A gallerist once told me that I needed to figure out a way to get naked people in my pictures: ‘those would totally sell’, he said.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

Spring or summer months. Studio visits with students over coffee. Time to photograph. Bicycle riding with the family.

There are those days when as a photographer it seems as if the world is collaborating with you and the pictures come in a rush. We need days such as this to counter the ones where we toil away at an idea making what might only feel like steps backwards.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026