Ingvild Melby: The Present is Woven with Multiple Pasts

©Ingvild Melby

Projects featured this week were selected from our call-for-submissions. We will be accepting new projects for review from April 4th-10th, 2021. Today, we are looking at the series The Present is Woven with Multiple Pasts by Ingvild Melby.

Ingvild Melby has a background in biology (with an emphasis on ethology) and a Bachelor’s degree in Art History. She is currently undertaking a Master’s degree in Art history at the University of Oslo. Her photography centers on our relationship with nature. In her work, Ingvild blends elements from dream and reality, combining staged and documentary photography.

Ingvild was a finalist in the 2018 Lensculture Art Photography awards and was named one of Photolucida’s Critical Mass top 50 photographers in 2019.

The Present is Woven with Multiple Pasts

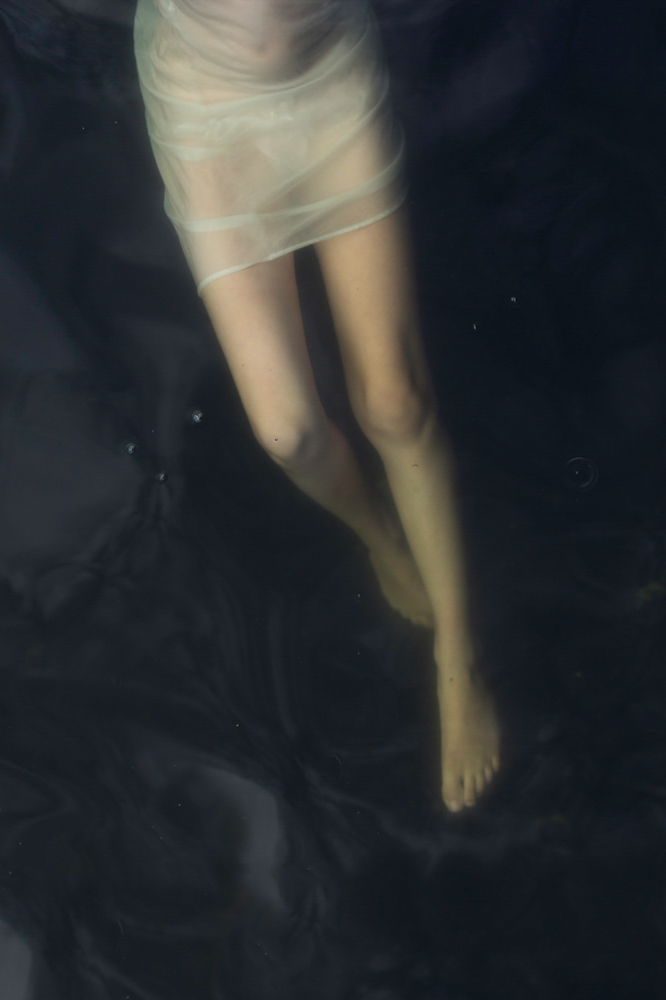

As a child I lived abroad, however we would spend our summers at home in Norway. Our cabin lay nestled between the black water of the Nordic ocean and the forest, far removed from the big city I was used to. Coming home was a strange experience. The place I knew so well felt both frightening, enticing, familiar, yet strange. The feeling that something lurked behind the trees or under the surface of the ocean made me uneasy. I would lie awake listening to the quiet and startle with every unexpected sound. Drifting in and out of sleep, hypnagogic images would play tricks on my mind.

I’m a mother now and my kids play in the same forest I used to. We haven’t had any snow this winter. Yesterday my daughter picked a flower where there shouldn’t be any before May. I worry. The forest yet again seems strange and unfamiliar, but not for the same reasons. Something new and foreign has crept into our forest and disturbed its balance. At night my maternal fears play out as in a dystopian fairy tale; a strange and confusing tale, in a world that no longer feels safe.

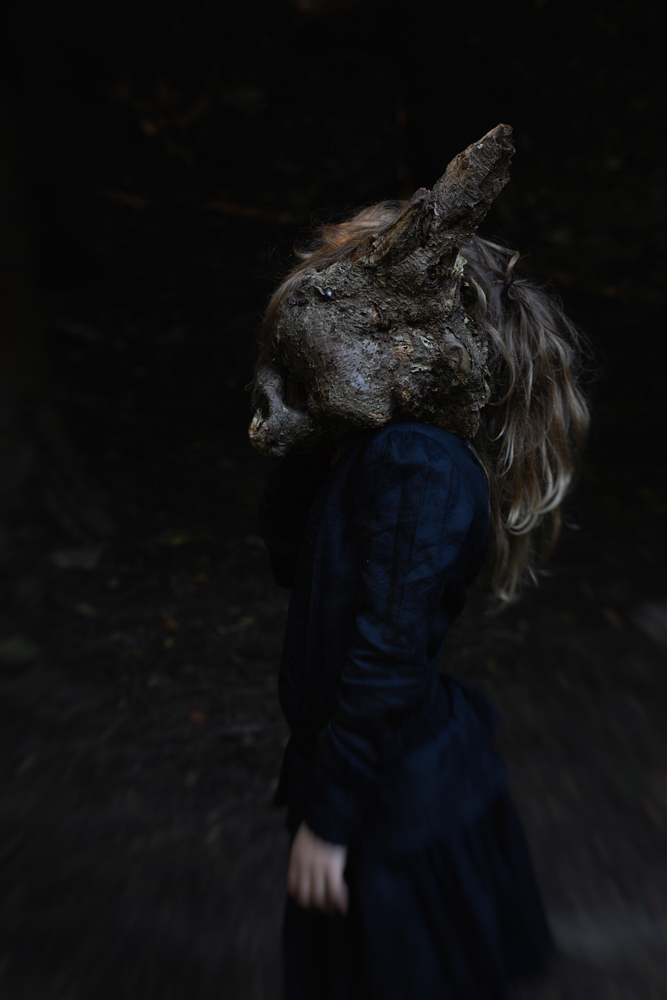

This project was inspired by the stories I was told as a child and reflects the fears I have for the future of our next generation and the planet we are leaving them. Folktales and myths emerge in time of upheaval and from histories grimmest moments. They help us deal with our fears and make sense of the world. They also often function as cautionary stories, moral guides and tales of warning. Now, more than ever, it seems we need new tales to lead us through our troubling times.

Daniel George: You have been visiting this place since your childhood, so it is obviously a location with which you are intimately connected. What lead you to begin making photographs here—with the intention of describing or alluding to something much larger, like climate change?

Ingvild Melby: When I first began photographing in this location it wasn’t with the intention of using the images in a larger project. I was simply spending time in a place that my children and I have a strong connection. However, when I started I quickly found that there is something about the light there that is amazing and that also brings me right “back” to when I was a child. Spending time in the forest also made me remember the stories I was told as a child and that my cousins and I often played or reenacted in the forest. In this sense, the forestscape as a bearer of collective memory emerged. Sharing these tales with my children made me more aware of how these tales often function as “warnings” against the hidden dangers of the forest and in life in general. At the same time, I was becoming increasingly worried about the changes I saw in the forest that I linked to climate change and I had been thinking about doing a project about this for a while without finding a way of approaching it that had not already been “done”. Remembering the tales from my childhood sparked the idea of using the visual language of fairy tales to draw on their “cautionary” aspect.

DG: Your children are the main subjects in your photographs. However, beneath the surface it feels more autobiographical. Through them, you are addressing things like your relationship to place and your fears of the unknown/unseen. I am interested in hearing more about your choice to involve your kids in playing out this role.

IM: I think having children has made me rediscover and rethink memories from my childhood. Seeing the forest through their eyes opened up the forest again as a place of mystery and wonder, but also as a place to confront your fears. Something I think many people can remember or relate to when thinking back to their own childhoods. When looking through the images I found that I was unintentionally alternating perspectives from that of the watchful observing parent and that of the experiencing child, immersed in the forest. Playing around with the images I found that this shift in perspective could be used to produce an additional layer to the project. When it comes to why I use my kids it was something that came about naturally. They have the same strong connection to the place as I do. They went to “nature kindergarten” and spent every day in the forest and as they have grown older they have also become very involved in youth organizations that deal with climate change. It was, therefore, natural to involve them in the project and by involved I mean not only as “models”. It became a collaboration between us, with them coming to me with their ideas and their concerns. However, although my children are in many of the images my intention was to make a series that hopefully others can relate to as well. I have, therefore, for the most part, concealed or obscured their faces so that the viewer, hopefully, more easily can “step into” the story and relate to the images.

DG: The strong, narrative characteristic of your photographs is what initially compelled me to read further into them. You also mention the inspiration of folklore and myth within this project. How do these images effectively function as cautionary tales?

IM: Folktales and myths have often emerged in some of history’s grimmest moments. They can help us deal with our fears and make sense of the world. They may also function as cautionary stories, moral guides, or tales of warning. In this project, I wanted to try to draw on this function, but at the same time engage with fairy tales from a contemporary point of view in the sense that I draw inspiration from tales, myths, and the visual language associated with them, but my intention was never to replicate a story I have heard. In this project, something new and foreign has crept into the forest and disturbed its balance. In some images, you might find subtle references to climate change and in others, nature has taken on a corporeal quality that may remind us of how our fate is bound to that of our natural surroundings. If these images can function as cautionary or not I will leave it up to the spectator.

DG: How would you say that your background in biology and art history informed your approach to this project? And in your creative practice in general?

IM: With a background in biology, I guess it is only natural that nature has such an important place in my work. A few years ago I went back to university and I am currently undertaking a Masters’s Degree in Art history at the University of Oslo. I will be handing in my dissertation this spring. I of course find a lot of inspiration in the art world, in writing about art and discussing art. I am especially grateful for having Professor Bente Larsen as an advisor. She is exceedingly generous with her time and always challenging me in ways that makes me grow as a scholar and has broadened my horizon. Lately, I’ve been looking at artists as diverse as Frida Orupabo (whose photographic collages I am writing about in my thesis), Kathe Kollwitz, Alina Szapocznikow, Louise Bourgeois, and Todd Hido. Hido has done a project in Norway that broaches some of the same questions. A project I find exceedingly beautiful and resonates with me in so many ways.

DG: In our email correspondence, you mentioned that this work consists of multiple chapters and is constantly evolving. Could you talk more about why you feel it is important to continually expand the series? At what point, if any, will you have reached a conclusion?

IM: That is a great question. I think it will naturally find its conclusion at some point, but when I am not sure. The project started around 2017 and as long as I keep finding new ways of seeing the forest I guess will keep photographing there. Having this place right “at my doorstep” has been a gift the past year and given us a place to escape from everything covid related. I have started another project, but that has been put on hold due to travel restrictions.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography & Anthropology: Raquel Bravo Iglesias, “Mato Grosso”May 1st, 2024

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024