Focus on South Africa: Tshepiso Mazibuko

In this second iteration of “Focus on South Africa” I wanted to include features on photography platforms, collectives, and teaching organizations in addition to artist profiles. In South Africa many photographers do not begin or advance their careers in secondary institutions, but rather through organized workshops, short courses, and extended mentorships. And while many Americans may be familiar with groups such as the Johannesburg-based Market Photo Workshop, a number of others have been established in recent years that are impacting the photography landscape in South Africa. These groups–and the networks of educators and mentors that work with them–are representative of a long-standing pattern of investing in and committing time to future generations of image makers that extends back to the Struggle era of the 1980s and 1990s and an “each one, teach one” practice among photography professionals. By learning more about the work of these groups we gain insight into the interests and concerns animating early-career photographers in South Africa, many of whom come from disadvantaged backgrounds that are traditionally underrepresented in the field, and who could not pursue the medium absent the support of the groups such as those profiled here. Two of the artists featured this week — Tshepiso Mazibuko and Jansen van Staden — have developed their work with support of Of Soul and Joy and Photo:, respectively. – Meaghan Kirkwood

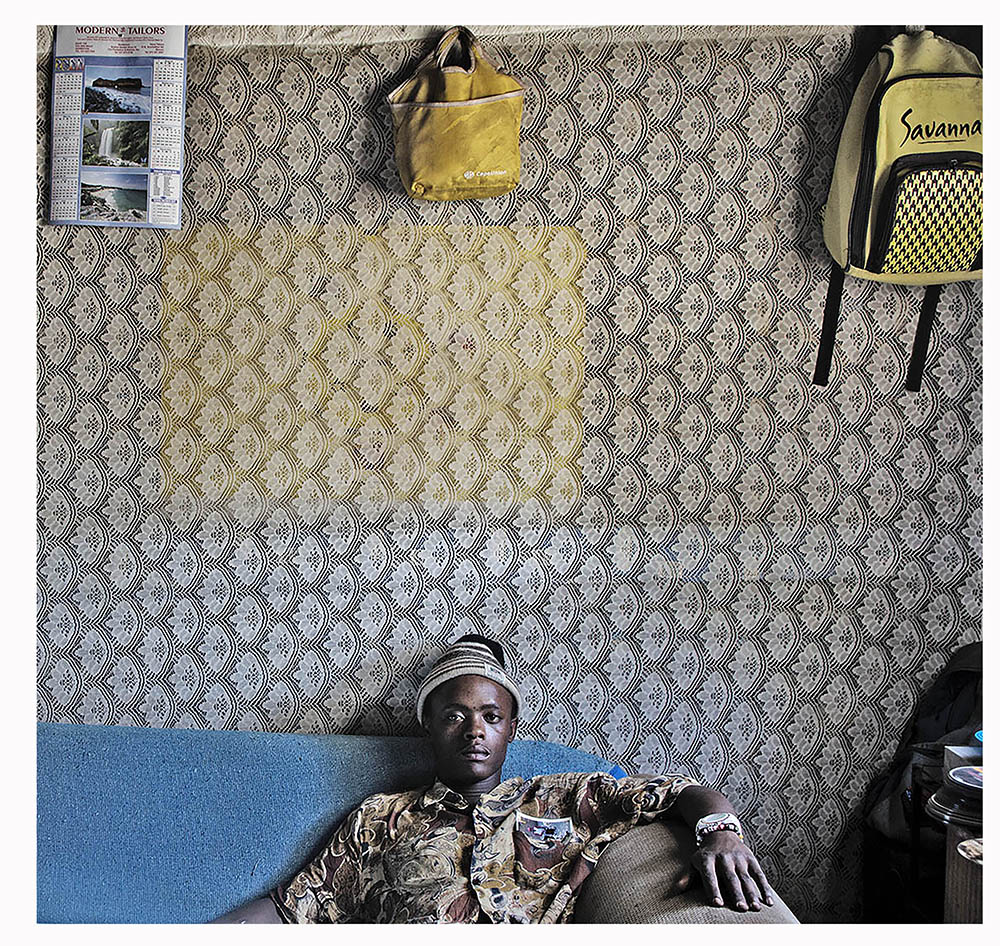

Tshepiso Mazibuko’s empathetic series “Ho tshepa ntshepedi ya bontshepe” puts forward a voice that is often underrepresented in the photographic community: a young black woman reflecting on her community, its promise, and the reality of the crippling economic situation for young people of color in South Africa. Mazibuko’s series explores the experience of “Born Frees” in her township of Thokoza and the structural inequities that continue to limit a generation that grew up with the promise of equal opportunity. The name “Born Frees” refers to those born after 1994. This generation never experienced life under the confines of apartheid, but has grown up impacted by situations that limit social and economic mobility.

Mazibuko describes herself as a storyteller and initially planned to pursue writing. “I always knew that I was very inquisitive,” she says, “I always questioned things.” But a workshop with the Of Soul and Joy program introduced her to photography. As a young artist she found voice in the medium, and was drawn to its ability to explore personal and universal stories. “Photography,” she recalls learning, “had this ability to capture, not even emotion, but a feeling; if you bond with the people that you photograph it comes across in your images.”

Through the Of Soul and Joy program Mazibuko became familiar with the work of other South African photographers, artists that inspired her to the potential of the medium. Together with the group she visited an exhibition of work by Santu Mofokeng, which made a deep impression on her. “How he portrayed townships was initially what influenced me as an artist to say, you know what? I want to add my voice; this is how I would like to represent, if you could say, my people.”

The Of Soul and Joy project supported Mazibuko with a scholarship to study at the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg, an institution she was drawn to because of its connections to artists like Mofokeng and Andrew Tshabangu. There, she says, is where she found new purpose and direction for her work: “I think the actual artist and the storyteller in me began at the Market Photo Workshop” she recalls. At the Market Photography Workshop, Mazibuko learned quickly where her strengths and interests were, and where she wanted to make an impact as an artist. “I was particularly interested in history and how the black body is represented,” she recalls, “I was interested in how I could create a point of reference for other generations…because I noticed I could not even do research about the town that I come from without sourcing from stories done by photographers that were stationed there to come and report.”

After graduating received a Tierney Fellowship to pursue a long-term project, which led to the production of her series, “Ho tshepa ntshepedi ya bontshepe.” Mazibuko locates the beginning of her project as an impulse to examine the gap between the promises made to her generation and their lived reality. “I wanted to tell a story about Born Frees and our struggles,” she says, “now we’re living in an Apartheid-free South Africa and there’s an illusion that everything now is okay for the black youth, but that is not the case.” Mazibuko describes the challenges of attaining economic stability in a nation with high unemployment, particularly among those under 35. “We were told to go to school, go get educated. You’re going to be successful and become somebody. But then when you do all the steps that they told you to do, you end up at the same place.”

Reflecting on the beginning of the project Mazibuko recalls dealing with feelings of anger. Prior to working on the project she had traveled to Europe for a residency, and struggled a bit on her return. Traveling gave her “a taste of what one would say is the soft life or the nice life?” she remembers, “and then when you come back, you’re actually still in this.” She found herself feeling resentment towards her own position in society, a feeling that shifted as she began to work on the project. Once she started photographing, however, she says, things changed. “I started telling my story to the people that I photographed. It started to be a project of empathy, it wasn’t a project of anger anymore.” In response to this shift within herself she altered the course of her project to focus less on revealing the pain felt by youth due to the economic circumstances, and more on their perseverance. “We all know that we are in the same boat, but actually we decide to be happy everyday.”

This shift in her own perspective changed the format of the series. Before she had been weighed by trying to represent the grim statistics of youth unemployment and economic distress. “They were complicating the photographing process for me; it started to feel like an academic piece of documentary; I felt detached from it.” She began photographing more of the youth culture itself in Thokoza and the stories she shared with her subjects. “It was no longer from a high pedestal of seeing or trying to point out people are not aware,” she says “actually everybody is aware. I think we just choose to focus our energy on different things.” This new focus inspired the series title, a Sesotho proverb meaning “We need to believe in something that will never happen.” Mazibuko’s images speak to a tension between the weight of outside circumstances and the vibrant energy of the township youth. Her portraits also reveal the connections she develops with her subjects; though intent, the gaze of her sitters focuses beyond the camera onto the photographer herself, a peer in the struggle.

I asked Mazibuko if her series was optimistic. “I don’t know,” she said. “I would hope when somebody views the work there is a sense of hope, a sense of intimacy.” But, she continued, “I also know that photography is no Messiah, it can’t change situations. But I think for me if I start creating dialogues through my work, that’s when I know that I’ve at least achieved a bit of something.” Importantly, Mazibuko does find optimism in the photography community developing in South Africa. “You have a whole lot of more young black South African photographers telling their stories,” she observes, “the photography scene now is full of identity stories and which is a beautiful thing to see during our time.”

To learn more about Tshepiso Mazibuko’s work you can follow her at @mazibuko.tshepiso

Meghan L. E. Kirkwood is a photographer who researches the ways landscape imagery can inform and advance public conversations around land use, infrastructure, and values towards the natural environment.

Kirkwood earned a B.F.A. from Rhode Island School of Design in Photography before completing her M.F.A. in Studio Art at Tulane University and PhD at the University of Florida. She currently works as an Assistant Professor of Visual Arts at the Sam Fox School of Visual Arts and Design at Washington University in St. Louis, where she serves as area head in Photography.

Kirkwood’s work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows at venues including Blue Sky Gallery (Portland, OR), Filter Space (Chicago, IL), Bangkok Art and Culture Center (Thailand), ArtSpace Durban (South Africa), Colorado Photographic Arts Center (Denver, CO), Rosza Art Gallery (Houghton, MI), Plains Art Museum (Fargo, ND), PH21 Gallery (Budapest), Midwest Center for Photography (Wichita, KS), Yost Art Gallery (Highland, KS), and Montgomery College (Tacoma Park, MD).

Her photographs are held in several private and public collections, including the RISD Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, University of Idaho, Minot State University, North Dakota Museum of Art, and the University of Florida Genetics Institute. Her work has been featured in publications such as Lenscratch, Don’t Take Pictures, Oxford American, New Landscape Photography, Landscape Stories, Don’t Smile, and Ours.

She has received numerous awards and fellowships to support her research, including from the Crusade for Art Foundation, selection as a Center Santa Fe Top 100 Photographer, full fellowships for graduate research at University of Kansas, Tulane University, and University of Florida. She has also received full funding to participate in artist residencies through the National Parks Service, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Lakeside Lab.

In tandem with her studio practice, Kirkwood also researches in the fields of African art and the history of photography. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Kansas, where she researched African monuments designed and built by North Koreans, a study that was published in A Companion to Modern African Art (eds. G. Salami and M. Visonà). Her dissertation examined the uses of landscape imagery by contemporary South African photographers. Her writing on photography has been published in Lenscratch, Social Dynamics, Exposure, and Photography and Culture.

Kirkwood is a native New Englander, but lives together with her family in St. Louis, Missouri. When not photographing or traveling, Kirkwood trains for and competes in marathons.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026