Text + Image Ryan Bakerink: If I Knew Then…

This week are are looking a few of the many ways that photographers are using Text + Image as a way to expand the concept of storytelling. We will feature projects that with the addition of text, allow for the subject to have a voice in the presentation, we will feature several photography book projects made more compelling with the addition of text, we will feature text as a creative element that elevates the work with an added layer of narration, and we will share work that has inspired text. – Aline Smithson

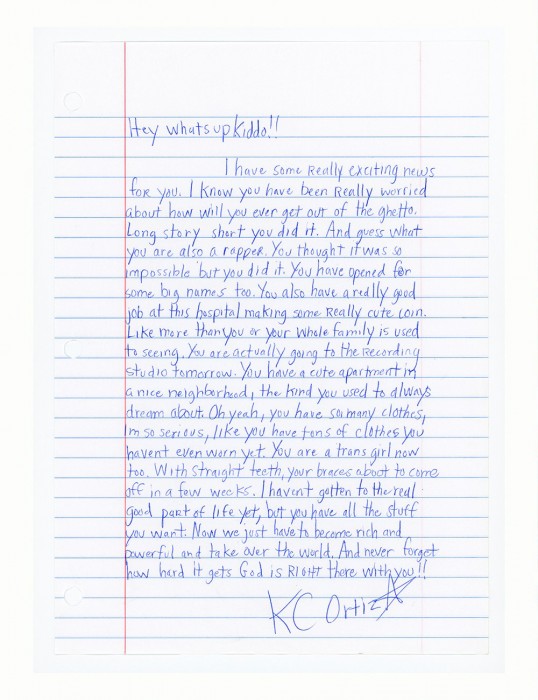

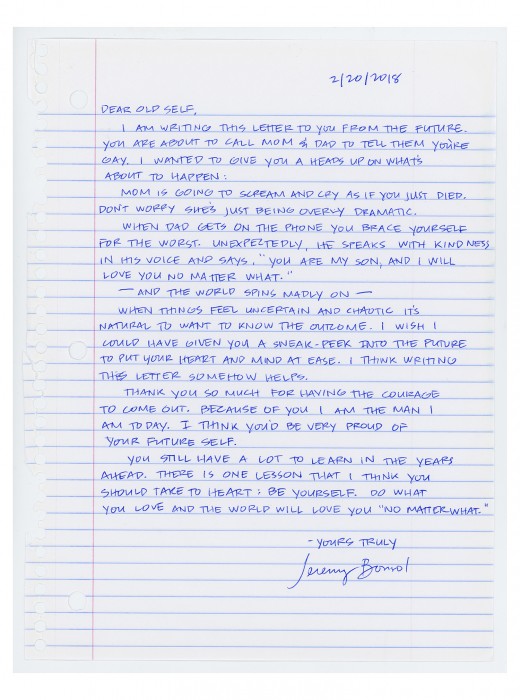

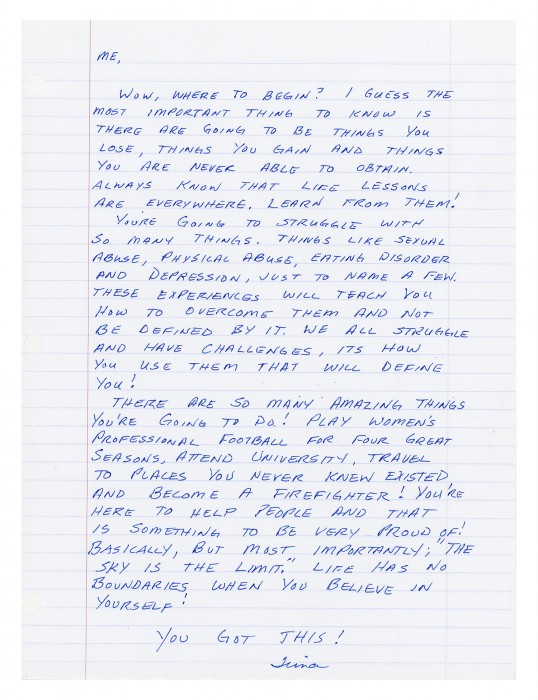

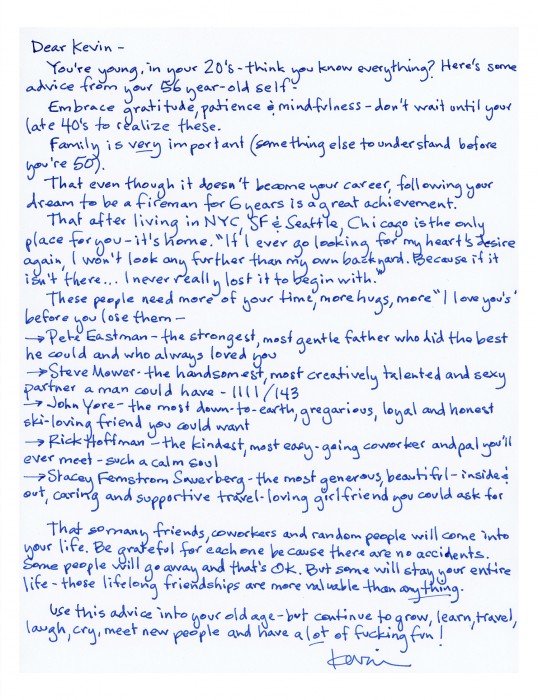

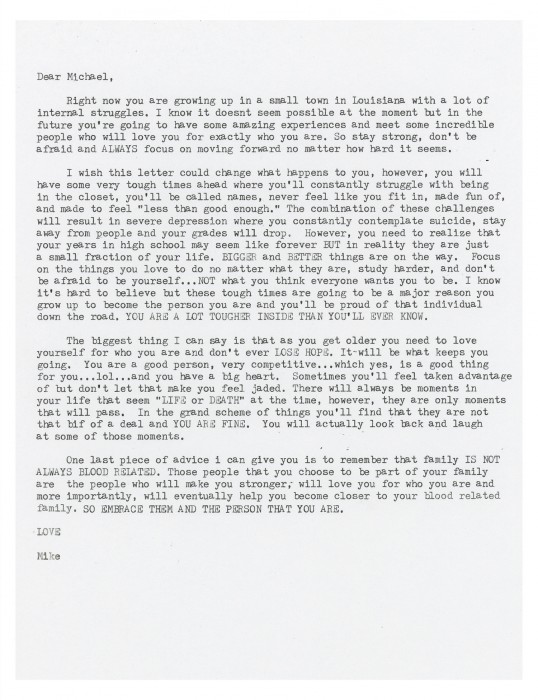

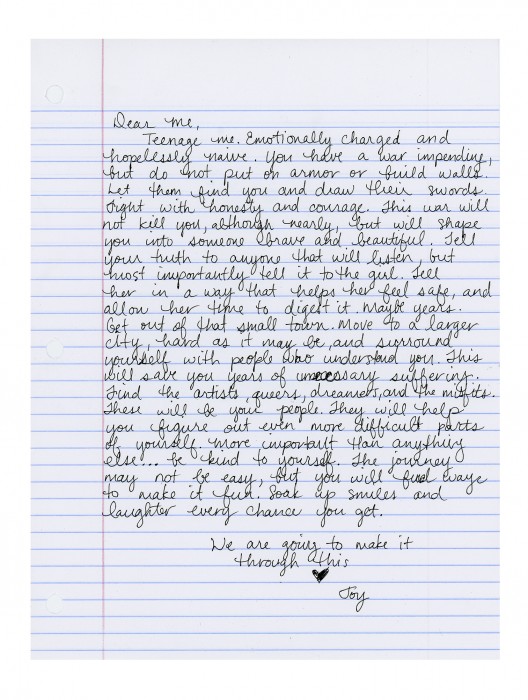

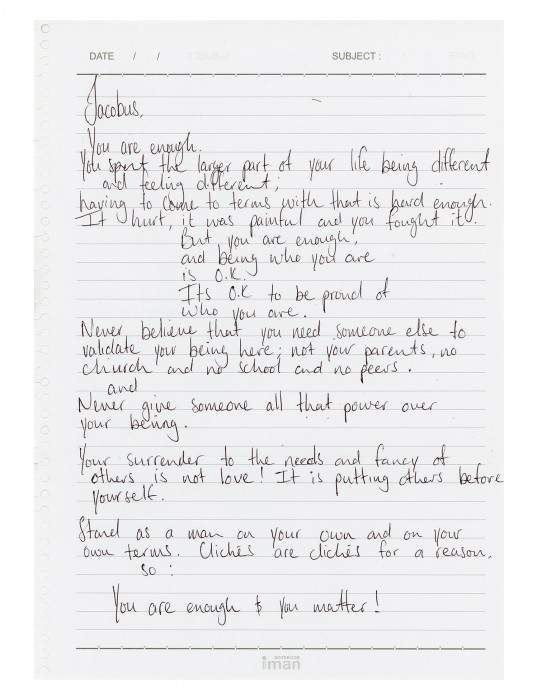

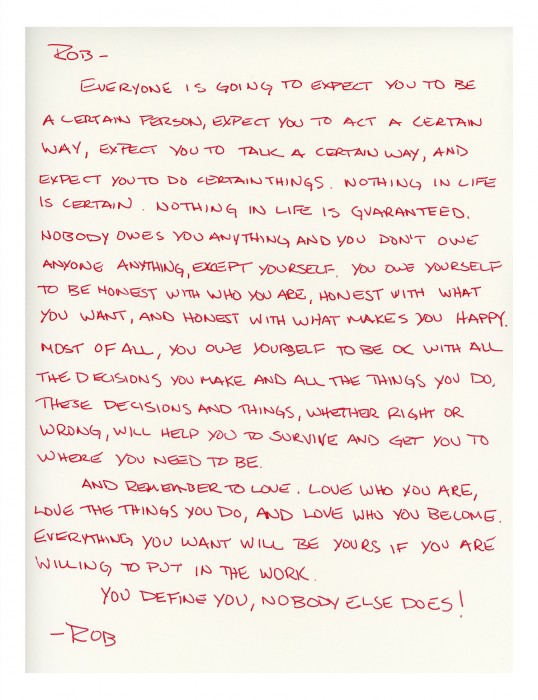

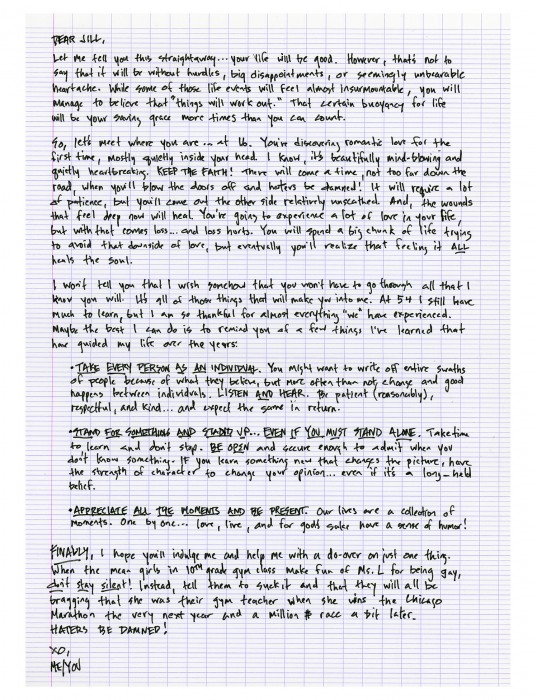

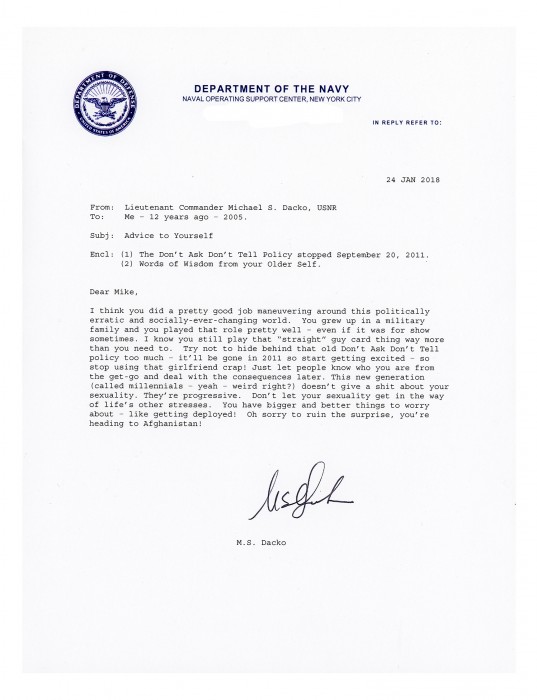

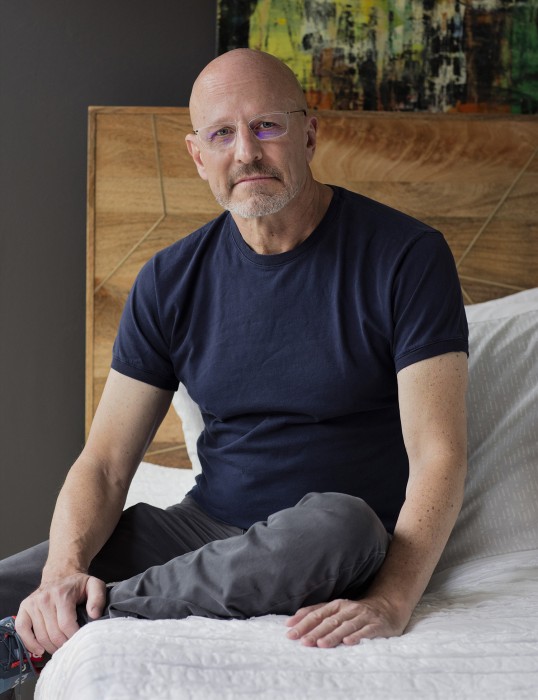

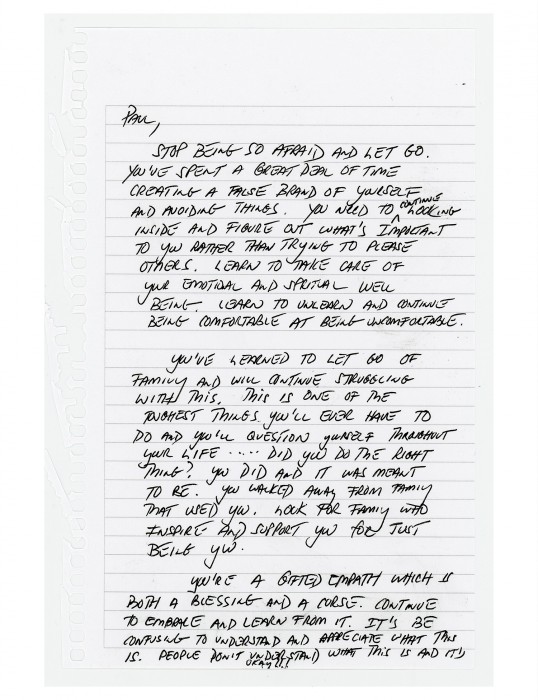

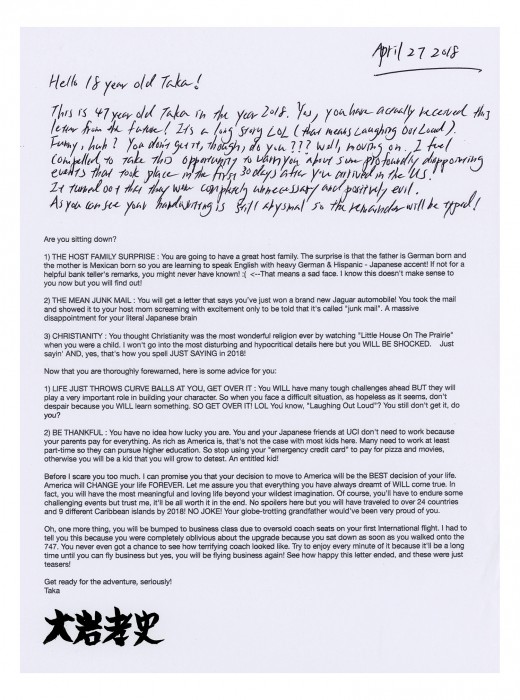

In his series If I Knew Then…, Chicago photographer Ryan Bakerink lets his subjects tell their own stories. Started as a way to bring awareness to mental health issues in the LGBTQ+ community, Bakerink takes a photograph of his subject and asks them to write a letter to their younger selves. They can say anything: what they’ve learned, what they wished they knew, words of advice. The letter is then paired with their portrait and suddenly a simple premise becomes a musing on the progression of life, lost hopes and dreams and the beauty of persevering in a world that can be cruel and unaccepting. The portraits are confident and quiet. The letters are heartbreaking and joyful, sometimes angry and sometimes hopeful. When amalgamated, they make each other come alive and a sense of self and humanity is given to these “stilled lives.” Below is an interview with Bakerink that touches on his upbringing, photographic methods, and how he finds inspiration in unexpected places. An interview with Bakerink follows.

Ryan Bakerink is a photographer in Chicago, IL focusing on social issues and counterculture lifestyle, specifically within the music industry, off the grid communities, travel, and portraiture. Ryan seeks to stretch his on personal and social boundaries by searching for authenticity in the world around him. Having grown up in a rural farming community in south west Iowa, the fuel for Ryan’s passion is to expand his horizons beyond what was imaginable in his youth. The ultimate goal of Ryan’s work has been to pull the curtain back and expose the general public to lifestyles, communities, and places that have been overlooked to help provide a greater understanding of human nature.

If I Knew Then…

I have a strong belief that art can be a catalyst for social change. As a gay photographer, I’m interested in using my craft to help others. This body of work focuses on mental health in the LGBT+ community. Each piece features a portrait paired with a handwritten letter that the subject writes to their younger self, prior to coming out. The letters contain advice which could address the subject’s sexuality, career advice, relationship advice, career advice, or any other advice that is important to the subject. The letter gives the audience the unique opportunity to experience this internal dialogue and connect with the subject on a deeper, more intimate, and emotional level. The work is meant to be therapeutic for the subject but also to serve a support network for those who so desperately need one.

Elizabeth Wayne: How did you get started in photography? What drew you to photographing the “counterculture lifestyle and off the grid communities?”

Ryan Bakerink: I grew up in a small town in Southwest Iowa with a population of 500 people. I did not have cable television, and the internet didn’t become popular or accessible until college. Hence, my only exposure to any culture was through my father’s national geographic magazines and my Mother’s rolling stone magazines. I read every issue of both magazines from front to back and saved many of them. The two things that stood out to me most in Rolling Stone were the incredible musician portraits from photographers like Annie Leibovitz, Mark Seliger, David LaChapelle, and Danny Clinch, and the stories and images of the underground music scenes in the ’70s, 80’s and 90’s. The portraits and stories in Rolling Stone Magazine were the first real spark that inspired me to become a photographer and my curiosity drew me to these counterculture lifestyles. I was drawn to the incredibly creative portraits and was fascinated by these stories that seemed so far removed from the life I knew. As I spent time with National Geographic and learned more about other off-the-grid communities within different cultures across the globe, that curiosity continued to grow. Since then, there hasn’t been a time in my life where I haven’t tried to seek out these communities, if not to document them to simply be aware of them.

EW: Describe your process for finding the subjects for “If I Knew Then”? Do you seek them out or do they submit their stories themselves? How do you think this impacts the project?

RB: Other than a few exceptions, I seek out most of the subjects. I started the project by photographing a few close friends to get the project off the ground and see if the images would work both esthetically and emotionally. Once I established that there was something there, I used the images of friends to pitch the project to other subjects that I didn’t know. I’d reach out to people on social media or ask friends if they could recommend people. Whenever I travel to a different city, I try to find at least one or two people to participate. I want to ensure that I have subjects from across the globe to have a more inclusive perspective across different regions. I first approach the subjects with the concept to let them know what the goal of the project is, how I hope the project will help others, and that the work will eventually be published as a book. Because I am asking the subject to write a deeply personal letter, I want to ensure that anyone I work with is comfortable with participating. Word of mouth has been beneficial as I will work with a subject, and they’ll say something like, “I know who would be great for this; they have an incredible story to tell,” and they will put me in contact with that person. This approach probably impacts the project as any single person’s reach is somewhat limited; however, I try to ensure that as I continue to expand the project, I try to be more inclusive of a broader range of age, gender, identity, etc. The more pieces I create though, the more others will recommend friends which helps expand the project beyond my own personal network.

EW: Portraits often tell a small part of a larger story. How does pairing a portrait with the subject’s letter expand the narrative?

RB:Pairing the letter with the portrait helps expand the subject’s story in a few exciting ways. First, the audience is provided the unique opportunity to experience the subject’s inner dialogue as they glance back and forth between the letter and the portrait. Second, the letter’s content helps expand the literal narrative. Still, other parts of the letter, like the handwriting, the paper the subject chooses, and other design elements like drawings, helps illustrate the subject’s personality, which can be hard to portray in a portrait. The components combined tell us more about the subject than one would typically experience through a traditional portrait.

EW: These letters are deeply personal, sometimes sad and other times uplifting. Which comes first, the writing or the portraits? What has been the most surprising part of reading your subject’s letters?

RB: In most cases, the portrait comes first. Once a subject agrees to collaborate with me on the project, I try to organize the shoot. During the shoot, I am able to have deeper conversations to spark creativity and build trust. By the time we create a portrait, the subject has likely at least outlined their thoughts, so having the opportunity to talk it through helps flush out those additional ideas and emotions. I prefer not to see the letter before photographing the subject. I do not want to see the letter prior to making the portrait as I don’t want to get hung up on something specific that the subject says, which could potentially influence me and force an idea that could lead to a less successful image. Instead, to ensure that the portrait is still personal, I ask the subject to think about environments that have meaning to them, and we try to work within that environment. Although the environment may not always have an obvious connection to the subject or the letter, it is another layer of telling the subject’s story.In some cases, I will coach a subject through their letter, and in other cases, the subject will write a few variations and choose the final letter to pair with the image.This process also ads additional layers of excitement beyond a traditional portrait project as half of every piece is owned by the subject. When I receive each letter, the initial surprise I experience is simply seeing how the subject approached their letter. What did they write? What paper did they use? How does it look visually? It is an absolute joy to receive the letters, read them for the first time, and experiencing how the subject approached them.What is also surprising is how honest the subjects are and their willingness to share deeply personal experiences. When I came up with the project, I assumed it would have an emotional impact, but not so much that it is hard to read more than a few letters at a time without an intense emotional response.

EW: “If I Knew Then” touches on the larger issue of mental health in the LQBTQ+ community. Did this project start as a way to publicize that important issue and if so, how have you seen LGBTQ+ mental health advocacy transform over the years?

RB:This project absolutely started as a way to publicize the importance of mental health in the LGBTQ+ community. I believe that art can be a catalyst for social changes so I had hoped that the project would serve as a support network for those struggling with their sexuality without anyone to turn to while simultaneously being therapeutic for the subject. Mental health has been a growing concern for years, and I am glad to see that people are becoming more open to speaking about it and sharing their stories without feeling ashamed. The topic of mental health in the trans community has had a big spotlight over the last few years, which has been incredible. The more visibility to this issue the better, and it has been great to see the courage that so many people within the community have had in recent years. However, there is still room for improvement and continued advocacy. Hopefully, this work will be an additional tool to further these efforts.

EW: In your bio you say that your ultimate goal has been to “pull the curtain back and expose the general public to lifestyles, communities, and places that have been overlooked to help provide a greater understanding of human nature.” Can you elaborate on what those aspects of human nature are? How has your other work impacted this series?

RB: The aspects of human nature I refer to are plentiful but often subtle. I grew up in a small farming community in southwest Iowa and currently live in a large metropolis. Combining this contrast with being well-traveled, I am fascinated with finding ways to highlight what makes humans both similar and unique. As much as I want to tell a story about a unique, off-the-grid community in California, I also want to try and illustrate how people in the slums of Kenya are like those in a well-off neighborhood in Chicago or how music transcends across all ages and demographics. There is a component of these efforts in all my projects and I hope that people can see parts of themselves in my work no matter what the specific subject is. I have a list dozens of potential projects, or projects in early stages that I hope to one day release as a series of 10-12 zines or books. Each zine /book will focus on a subtlety of the human condition that highlights everyday experiences or emotions with the intention of illustrating how humans everywhere share a lot in common, even in the most subtle of ways. I also have another Diptych project on the LGBT community that I intend to work on in the future that touches on a lot of the themes I’ve discussed (a greater understanding of human nature, different lifestyles, subcultures, etc) and will hopefully expand a specific narrative in a new way. I apologize for this “teaser” with very few details but I say this just to help understand my approach to projects.

EW: When looking at your work, I see themes of abandonment, loss, and being “the outsider.” Do you agree with that? Was that a conscious theme or did that only become apparent after the work was created?

RB: This is a fair observation and relatively accurate. Still, it’s also somewhat coincidental as those themes unintentionally turned out to be natural elements in some of the stories I’ve been trying to tell. My project “This is the way we disappear” is an obvious exploration of abandonment and loss. Although on the surface, this work seems to be what could be considered “Ruin Porn,” but to me, it’s more of a portrait project. The project stems from the Egyptian belief that you die twice, once when you take your final breath and then again the last time someone says your name. This concept interested me as I felt there can still be a physical monument left even after someone says your name. This physical monument to me serves as some sort of purgatory, a physical reminder of someone’s life, whether or not you knew anything about the people associated with it. Too me the project is an exploration of life, or at least a portrait of a life that once was. This theme is also evident in the work I’ve done in Chernobyl for obvious reasons; however, in my projects “Chicago 2020″ and “Lip Sync to a Car Crash,” it’s more circumstantial and less conscious. My project “Chicago 2020,” which will be published by Kehrer Verlag early next year, was meant to be a project of self-discovery to honor 20 years of living in Chicago and having moved to the city when I was 20. I sought out to create a project of joy, celebrating the city by capturing life in each of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods. Instead, the year 2020 turned out to be a year of loss, emptiness, fear, and tension. The project quickly evolved into a time capsule of Chicago during a very traumatic year, and the emotion I captured was the exact opposite of what I intended. These scenes were unavoidable in 2020. “Lip Sync to a Car Crash” is essentially a similar/sister project to “Chicago 2020″ but at a national scale, trying to capture those same themes across the country at the peak of a unique time in history.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025