Photographers on Photographers: Seth Cook in Conversation with Debbie Fleming Caffery

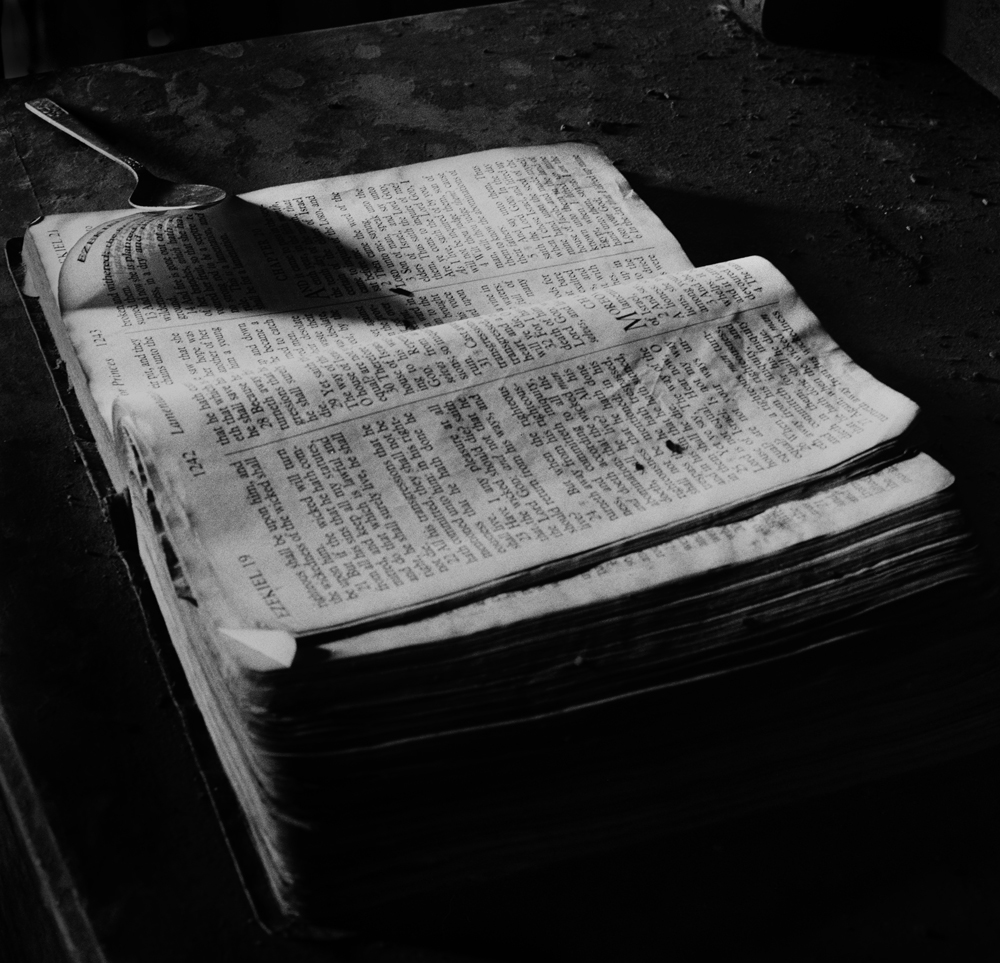

For this interview, I chose the life and work of Debbie Fleming Caffery. Growing up, Debbie was the first photographer whose work I ever felt connected with. Despite us both being from the Bayou Teche in Louisiana, however, we never crossed paths, and I found this interview the perfect opportunity to reach out to her. I first came across her work as an undergraduate at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette while working at my friend’s frame shop. One day I happened to find myself in front of her photograph “Lamentations For Princes,” being framed for a collector. Instead of working, I was captivated by the dramatic use of light and shadow draped across the scripture, with Polly’s spoon subtly saving her place in the background. Even without knowledge of her work, it felt like something was present within the image that I had never experienced before – that there was a more to the photograph than a visual document. While I took photo classes before this moment, it was then that I felt a deepening desire to pursue photography, wanting to encapsulate that same feeling with my work.

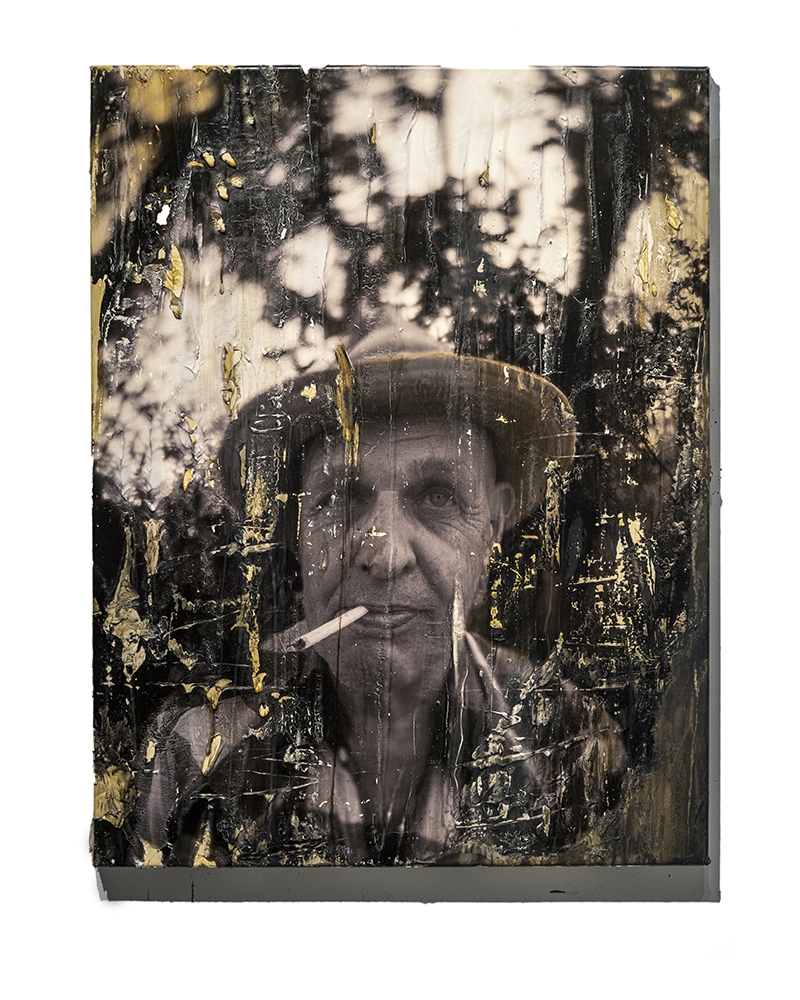

Debbie Fleming Caffery is highly regarded for her work in documentary photography and as a freelance teacher. Caffery has photographed the sugarcane industry and its community in Louisiana since the late 1970s. She has also photographed in rural villages in Mexico for many years, creating works that draw connections between those communities and the ones in Louisiana that were so familiar to her from her own upbringing. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Katrina Media Fellowship, Open Society Institute, George Soros Foundation, Lou Stoumen Award, San Diego Museum of Photographic Arts, Michael P Smith Documentary Photography Award, La. Endowment for the Humanities, and a “Picturing the South” commission from the High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia. Her work has been published by the Smithsonian Press, “Carry Me Home,” with a one-person show at the Nation Museum of American History, Smithsonian, Washington DC. Other books are “Polly” and “The Shadows,” published by Twin Palm Press, Santa Fe, Collection “L’Oiseau Rare”, Filigranes Edition, France, “The Spirit and The Flesh,” Radius Books, Santa Fe and “Alphabet,” Fall Line Press. Her work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum, New Orleans Museum of Art, Ogden Museum, George Eastman House, Library of Congress, National Museum of American History, Elton John Collection and many more. Her work is exhibited nationally and internationally. Her work is represented by Gitterman Gallery New York, Obscura Gallery, Santa Fe, Octavia Gallery, New Orleans, and Camera Obscura Gallery, Paris.

Seth Cook: Debbie, thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview. I’m sure you have been asked this many times, but I first wanted to start with what got you into photography? You would think that two artists from the same neck of the woods would eventually cross paths, yet I never found an opportunity to reach out or interact with you until now.

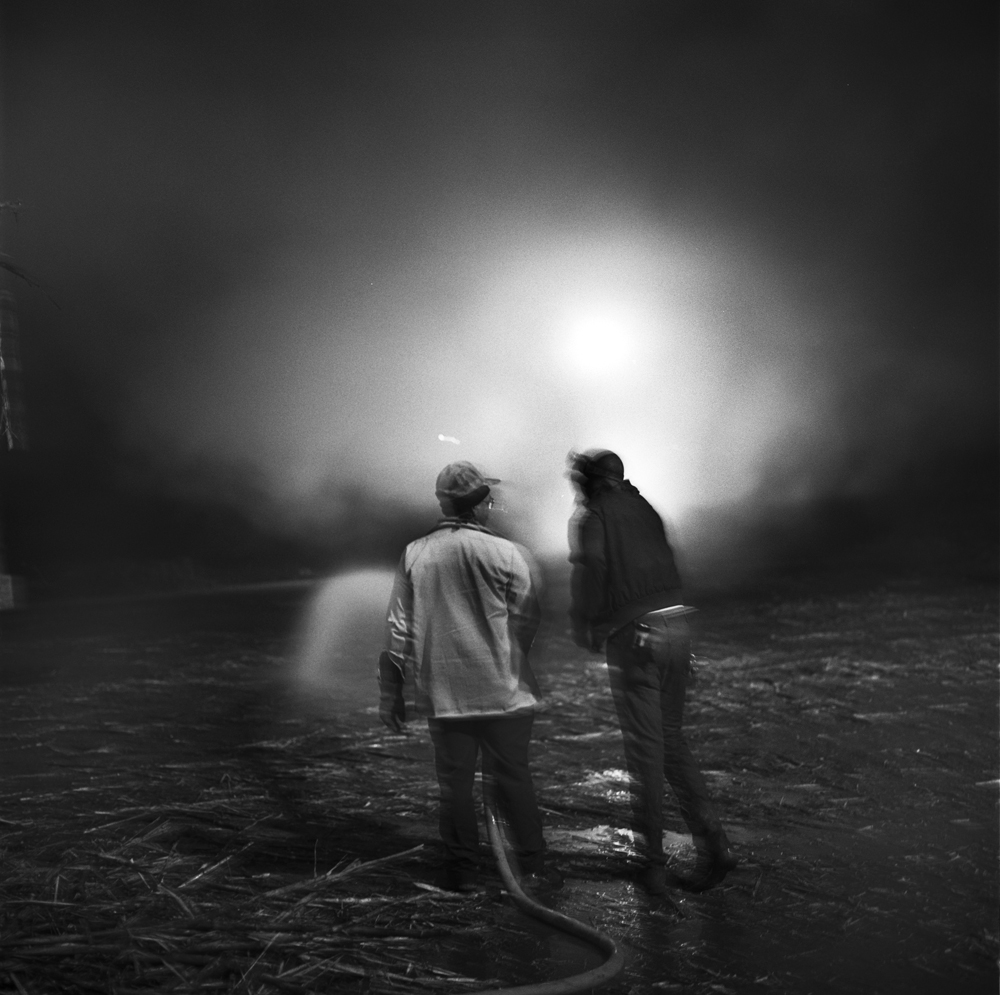

Debbie Caffery: Thank you for having me. Where did you live on the Bayou Teche? I was a fine art major at LSU and decided to switch to UL as I heard so many great things about their art department, it was a great move. There were two photo teachers, so I decided to take a photography class, and I fell in love with taking photographs. I had some great influence as my dad took photographs and movies and gave me his camera. I think the visual influences I had were, growing up, we lived across the bayou from a sugar mill. My brothers and I loved to watch the sugar being loaded onto the barges yet we were terrified for the workers on the barges falling into the bayou and drowning. We worried they could not swim. This image is etched into my mind. The smells, good and bad, still stir up memories to those moments.

Another important person that inspired me was my grandfather. I walked to my grandparents after school every day and often my grandfather would take me to a sugar mill in New Iberia. He would catch up on the news from his friends there on the cane harvesting and we would watch the cane be brought to the mill. He would also bring me to the sugar fields to see the cane burning. We often visited a friend who made cane syrup outside his grocery store while the cane truck passed in front, bringing cane to the mill.

SC: I actually didn’t know you went to UL. I also went to UL to receive my Bachelor’s. Also, I’m from a small town called Bayou Vista – we’re so small you’d have to really zoom into a map to see us. It’s incredible hearing how you grew up and how your environment influenced you. I wondered if you could talk a little more about how your environment impacted what you desired to photograph. Also, what equipment did you start with?

DFC: I started with my dad’s canon 35 mm. I spent so much time with my grandfather during sugar cane harvesting every year. I think that experience is etched into my heart and vision with great memories of my grandfather walking along the Bayou Teche after school to my grandparent’s house. He was usually waiting for me, and my grandmother used to have a homemade cake on her washing machine that was in the kitchen. When I was harvesting, my grandfather would take me on adventures; To a bar by the train depot and put me on a stool and give me a little bottle of Coca Cola. We would watch the train arrive or leave and he would have a beer and talk to his friends.

One day walking from school, there was all kind of commotion on the bridge, and I saw someone pulling a man in some net (I am not sure what it was), but he had drowned and it must have had something to do with my fear of the men on the barge loading the sugar, that they would drown, keeping watch over them. I have a photo of me getting into his car, which is a white Chevy, I remember throwing rosaries in the ditch nearby. I passed by my grandparent’s house the other day and drove the way I walked.

SC: The way you tell your history is so rich and beautifully vivid – like reading a book of poetry. As you described your experiences during the cane harvests, it got me thinking of your body of work depicting the cane workers. The way you captured light and shadow felt as though I was peering into someone’s soul. I wondered if you could talk about that body of work and how you felt as you photographed the cane workers.

DFC: Thank you. My grandfather introduced me to his favorite bar where old friends of his hung out. I love to take photos in Cantinas in Mexico, similar to the bar by the train depot.

I still photograph during the harvesting, not every year but if I don’t, I visit my sugar cane friends who have also been a source of inspiration. Many of the workers I photographed have died. Still, there is always a conversation about them.

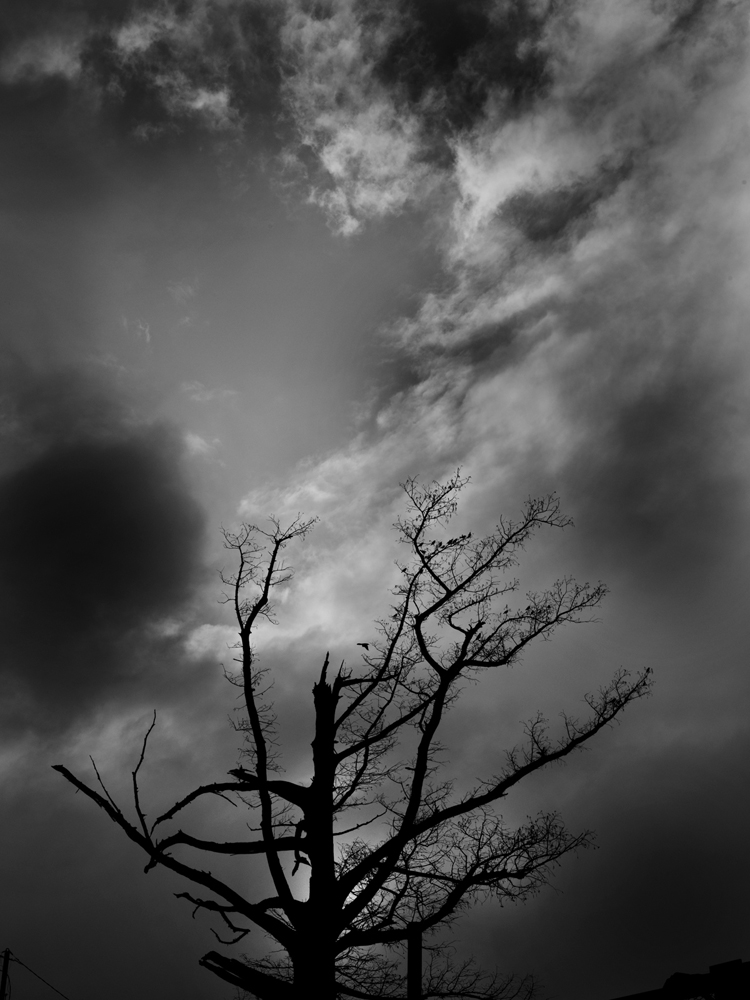

I visit a tree that I have photographed a lot and listen to the fabulous song “Up On the Roof” by the Drifters. “When the world starts getting me down, I go to see the tree instead of the roof.” I love the line, “I’ve found a paradise that is trouble-free.” When I see the arms of the tree stretching out and the tree still standing after it has been struck by lightning and hurricanes, I feel hugged by the tree! I suggest you listen to the Drifters song, ‘Up on the Roof’. I’ll try to explain the talking/listening deal tomorrow.

SC: I’d love to see that tree! When I was a kid, I would imagine the trees were giants – some good, some bad – and those with moss were older and wiser. I spent a lot of time venturing into the woods, especially because my family spent most of our time at baseball games for my older brother. I tried playing baseball, but I found the grass and bugs more interesting!

Next day –

SC: I listened to the song ‘Up on the Roof’ by the Drifters while driving to visit my girlfriend. I understand the song’s positive message and I feel like I really needed something like that to help me cope with my current situation. Thank you for sharing this. You mentioned before about talking and listening to your work, and I wondered if you can elaborate further on that?

DFC: I primarily work on projects for years and I will refer to my work in Mexico. I used to photograph for about 2 or 3 weeks, return home, have the film developed and then print. I did this off and on for many years.

In the early days of working in Mexico, I photographed in one city. I eventually returned to a small village in the mountains where I rented a house and primarily photographed there (a place I felt grounded and welcomed). I then started photographing in brothels and went to several cities to work. Over several years, returning to the same places over and over, always returning to the place I had established as my home in Mexico.

The reason I am mentioning this is because it’s the background where I photographed and learned so much combined with the years of photographing the sugar cane harvesting. Listening and paying extreme attention to conversations, I sometimes could not understand. Visualizing what I am hearing and photographing, which puts my mind in a silent yet visually active place.

I guess what I am trying to say is that listening is sometimes more important to get me to the moment you take the photo. Listening is an accumulation of seeing, hearing, and feeling. For me, it works to not just spend a short period of time on a photo project but to return again and again.

SC: I understand now. Thank you for elaborating a little further! We could shift the conversation a bit and ask you more about what led to your first big break in the art world. Would you mind elaborating?

DFC: Of course. I took my teachers’ advice and went to New York and asked him who I should show my work to. He said John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art. Their policy at the Museum was to drop off your portfolio with the secretary and pick it up in, I think 2 days. When I went to pick it up, the secretary told me Mr. Szarkowski would like to speak to me. I was brought into a room, and my photographs were spread out over the table. The first question he asked was, “What do you do every day?” After that, he asked me about my photography, and he said the museum would like to own some prints. He showed me which ones and asked if I would donate them. I said no. I was shocked by the question. Then he asked me the cost of my photos. I said $100, and that was fine with him. I had not thought about a price until the moment he asked. A few years later I went back and he bought, I think 3 more. I’d have to check my records.

I continued to photograph and add images to my portfolio, and I showed my work at Foto Fest in Houston, then to the Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, France. I made wonderful connections at both places. My first exhibit was in New Orleans at the Contemporary Art Center.

SC: Incredible. I sometimes wonder if that process has changed. I imagine technology makes things easier, but sometimes I’m not so sure. On that note, what is your opinion on where photography is headed and what advice would you give young, serious photographers?

DFC: Just knowing the situation in this country, I would advise serious young photographers to get as much education (masters degrees, etc) so that teaching is an option. I would take classes in commercial photography, editorial, etc., in order to be flexible in the field of photography as possible, as we really don’t know what the future will be like.

I think we could both agree that working on projects that you love is the most important thing, be devoted to yourself. It sounds simple, but I think it is the hardest to do, to keep yourself in focus.

SC: I couldn’t agree more. I want to think that things haven’t changed much, despite where technology is now. While social media is the current dominant language, I still see people passionate about photography and using it to tell their stories. I see my students garner respect and interest in film photography, deciding that digital isn’t enough for them.

This next question is personal to me, so please bear with me. The main reason why I wanted to reach out to you isn’t just because we are from the same area, nor is it because of your subject matter, use of light, etc. It’s because of how you capture loved ones – whether they’re family or friends, or perhaps even those you didn’t get to know very well but still treasured the moment.

We spoke a bit about my mother. I’m scared things might be dire for her, and I’ve wanted to photograph her and other members of my family for so long, but my family is more about privacy and keeping things secret and quiet. Despite being family, they most of the time refuse when I ask to take their picture, even at the most basic portrait. I’m finding it hard to get the words out right , but I guess what I’m trying to ask is how I can reach out to them? If you were in my shoes, what could be a way to get through to them? Is this a fruitless endeavor, and should I accept their wishes?

DFC: I would explain how important it is to document them for a family archive. I suppose they have supported you in your work…so as a gift to them for the love and support you want to photograph them and show your love and appreciation for getting you, understanding and nurturing you. You photographing them is giving them a great gift. I would say the images would be just for the individual or the family (again, for your family’s history). Give them the choice, photograph for yourself only and only give the individual the photos, agree not to exhibit, publish, etc. that might make them more comfortable.

When I was photographing in the brothels (paying everyone), there was one woman that did not want to be photographed. After me spending so much time there, she told me that she had changed her mind and would love to be photographed. I offered to send each person images and no one wanted them, except she did. I was fascinated with her the first day I started photographing, and she fell in love with my assistant. I love the images.

If you can get your Mother to agree, it would be great for her to see how you work and what you see. I think it would help her during this rough time.

Seth Adam Cook is an artist from the Bayou Teche region in south-central Louisiana. He completed his BFA in studio art from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 2015 and completed his MFA degree in photography from Indiana University, Bloomington in 2020. Shortly after receiving his bachelor’s, he became an active member of his local art community, taking part as a juror for Festival International de Louisiane’s 30-Year Memorabilia Exhibition. He also had a hand in helping his local galleries with charity events, workshops, and editorial work. In 2018, while earning his master’s, he gained recognition as a Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory scholar for his exploration and experimentation with laser-cutting technology. The results of which were presented at the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities 2019 Spring Symposium. In 2020, he was recognized by photoblog publisher, Lenscratch, taking part in their 2020 Student Prize “Top 25 to Watch List.” Within the same year, where he worked as their ‘Scholar in Residence’ where he accepted a ten-month residency with Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center in Cincinnati, OH. His work has been displayed nationally and internationally, including: Louisiana, New York, California, Colorado, Massachusetts and South Korea.

Follow Seth Cook on Instagram: @s.adamcook.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024