Figure Studies: Cathrine Alice Liberg: The Body as Temporal

This week in Lenscratch, we look at the work of seven artists, exploring the many iterations of the body in photography.

Cathrine Alice Liberg (b. 1988) is a Norwegian and Chinese-Singaporean artist living and working in Oslo. She received her MFA in Medium- and Material Based Art from the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, specializing in printmaking. Since graduating in 2019, she has exhibited both in Norway and abroad. In 2019 she received the KoMASK European Masters Printmaking Award in Antwerp, and the Norwegian Printmakers Fund’s Print Award at the National Art Exhibition in Oslo. She has also been nominated for the QSPA Inspirational Award for newly graduated printmakers.

Liberg’s first solo exhibition The Ghosts We Chase We Never Catch will open Nov 11 – Dec 18 at Galleri Norske Grafikere (Norwegian Printmakers) in Oslo.

Could you please tell us a little about yourself and your practice?

I am a Norwegian and Chinese-Singaporean artist and printmaker living and working in Oslo, Norway. I mainly work with printmaking techniques such as lithography and mezzotint, but my practice has always been heavily influenced by photography. For the past few years, my work has revolved around the classic family portrait. How can these seemingly private worlds represent fragments of larger national and global histories, collective memory, social structures and gender roles? Using my own archive as a point of departure, I explore both my family’s history of migration and diaspora, as well as our collective forgetting of the past.

Which artists do you look to for inspiration?

If I were to name one artist, it would be Rachel Whiteread. My favourite work of all time must be her Turner Prize winning work House (1993), in which she cast the inside of a house in East London that was scheduled for demolition. The plaster cast of the house’s interior stood on the site for 80 days after the building had been taken down. She made visible the empty space, and the result was haunting, unsettling and emotional. After all, it is the empty spaces – the spaces in between- that we live and operate in. The significance of negative space, and the balance between presence and absence, is something I always try to bring into my work.

Can you tell me how the series Do Not Keep Photos of the Dead came about?

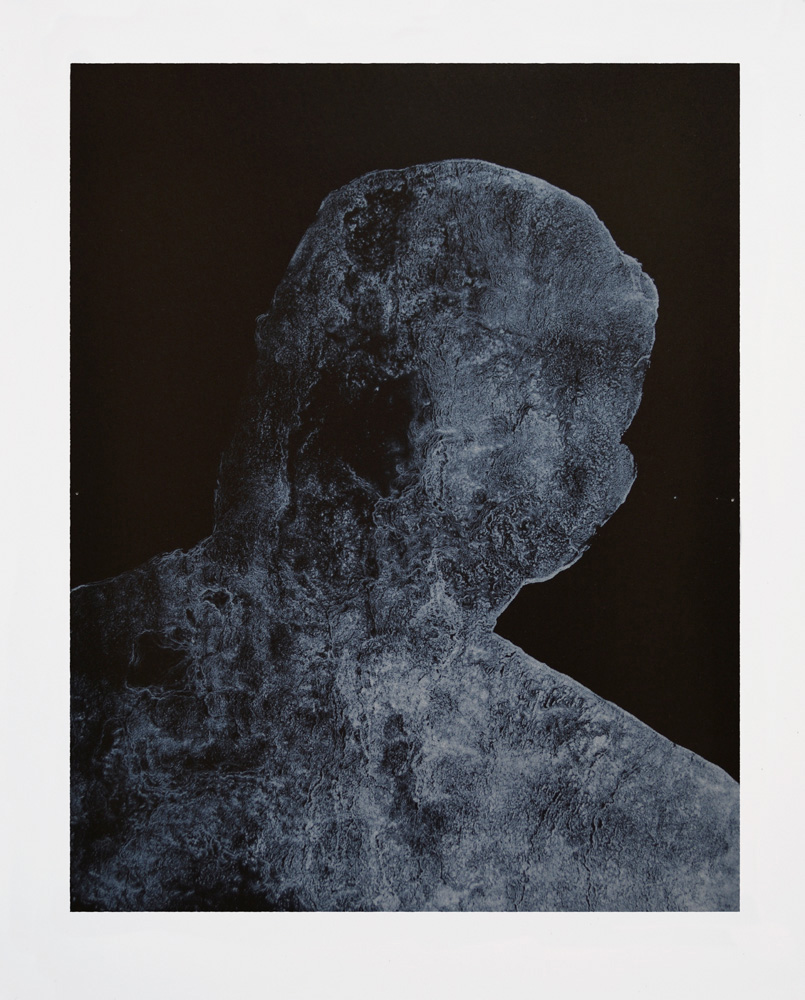

The silhouette figure has been a recurring theme in my work for several years now. It started when my Chinese grandma cut my late grandfather out of their wedding photo, claiming that pictures of the dead brought bad luck and bad “feng shui”. All that remained was his outline. The dualism of his silhouette intrigued me, because he felt both present and absent at the same time.

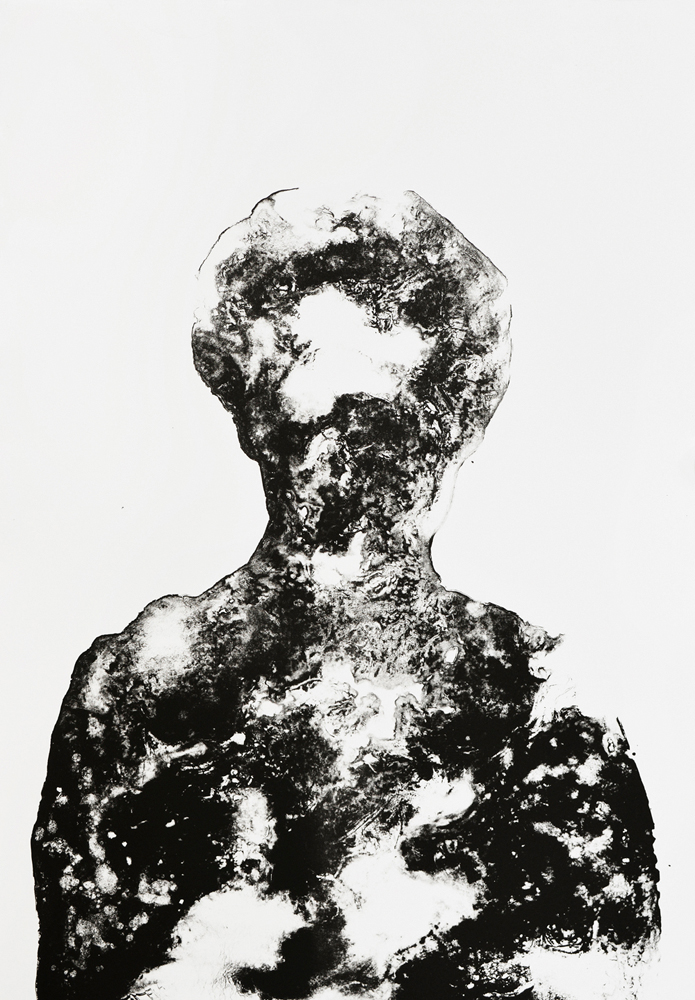

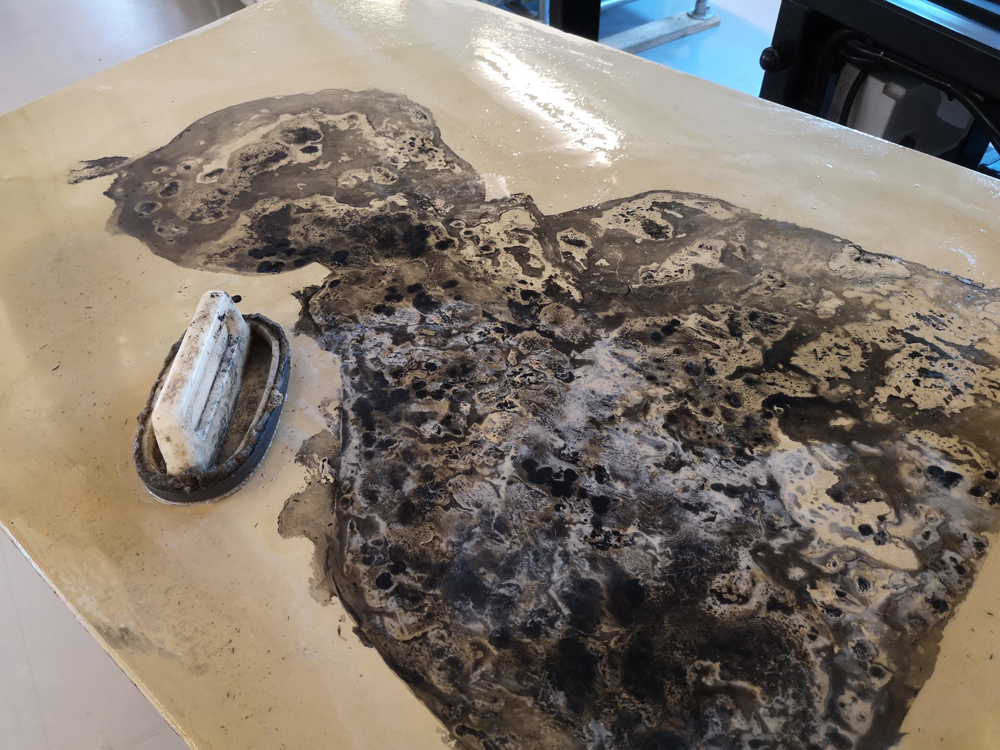

Remembering this story many years later, I began tracing outlines of photos of deceased relatives onto large lithographic stones. Lithography is a printing method invented in 1796 by Alois Senefelder, in which an image is drawn onto a lime stone, treated with acid and gum arabic, and then inked and printed onto paper. I filled my drawn outlines with liquid lithographic tusche, which upon drying created reticulation patterns. To me, the resulting printed figures resembled biblical salt pillars about to crumble, or smoke about to evaporate. Appearing to disintegrate, they navigated between my grandma’s desire to erase and my need to remember and preserve. They were fading, both physically and in our minds, but were continuously fighting their own obliteration.

How does photography inspire your practice both in general and specifically in this series?

Coming from a mixed Norwegian and Chinese-Singaporean family, different cultural perceptions of photography in relation to death have long influenced and inspired my artistic practice. My grandmother’s decision to cut my grandfather out of their wedding photo was such a stark contrast to how I had grown up regarding photos. Every Norwegian family I knew filled their staircase walls with black and white photographs of long-gone ancestors. To them, photography was a vital tool for remembering and preserving the past, whereas for some, like my grandmother, it was something to be kept away from the living. Do Not Keep Photos of the Dead became an attempt at consolidating these two opposing views.

You say these images are heavily influenced by photography’s relation to death and memory. Could you elaborate on this?

In his seminal work Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes identified the essence of photography as an Agent of Death, claiming that the photograph is something which will always belong to the past. From the moment the shutter goes off and the photograph is conceived, it will always be “that-has-been”, if not necessarily yet “that which is no longer.” By turning the living subject before it into an object, the camera always seems to conjure up Death whenever it is trying to preserve life.

How could I bring my family photographs back into the present and reactivate them?

One book that has been hugely influential to me is Geoffrey Batchen’s Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance. In his writings, he argues that a photograph alone is not sufficient enough to evoke memory. This is because it does not operate the way memory does. It is too concrete, and does not invite other senses such as touch and smell, which are greatly connected to mnemonic functions. That is why we have always been so obsessed with altering photographs to strengthen their emotional appeal, such as adding frames, locks of hair, pressed flowers, pieces of textile etc. This is why I also like to trace silhouettes from actual photographs, and rework them into paintings and prints. Simply tracing a person’s outline and making them life-sized makes me feel physically closer to them. To me, the act of drawing and printing counteracts the photograph’s role as an Agent of Death.

Who are the figures in this series? Are they the same person?

They are all different relatives whom have passed away. Some I knew, some died a long time before I was born.

What is next for you?

Right now, I am getting ready to open my first solo show in Oslo, which will showcase portraits which I have worked on over a period of five years. Do Not Keep Photos of the Dead will be included in this exhibition, and my idea is for the gallery space to operate as a kind of family photo album or scrapbook which one steps into.

The next project on my agenda is an illustrated book series of Italo Calvino’s beautiful novel Invisible Cities. Here I will also be using a mix of drawing and photographic printing processes, and all the books will be handprinted using photopolymer.

© Cathrine Alice Liberg, Do Not Keep Photos of the Dead Exhibited at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts, 2017

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025