Jaclyn Wright: Marked

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Marked by Jaclyn Wright.

Jaclyn Wright is a multi-disciplinary artist and educator from the Midwest. She received her BA from Southern Illinois University and her MFA from Indiana University. Her work combines traditional analog photographic techniques with contemporary digital methods, performance, and installation. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and published widely. Recent and upcoming exhibitions of her work include: Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (Salt Lake City), The Print Center (Philadelphia), OCT-LOFT (Shenzhen, China), SF Camerawork (San Francisco), Sabine Street Studios (Houston), SFO Museum (San Francisco), and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (Salt Lake City). Her work has been included in the collections at The Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, IL. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Photography at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT.

Marked

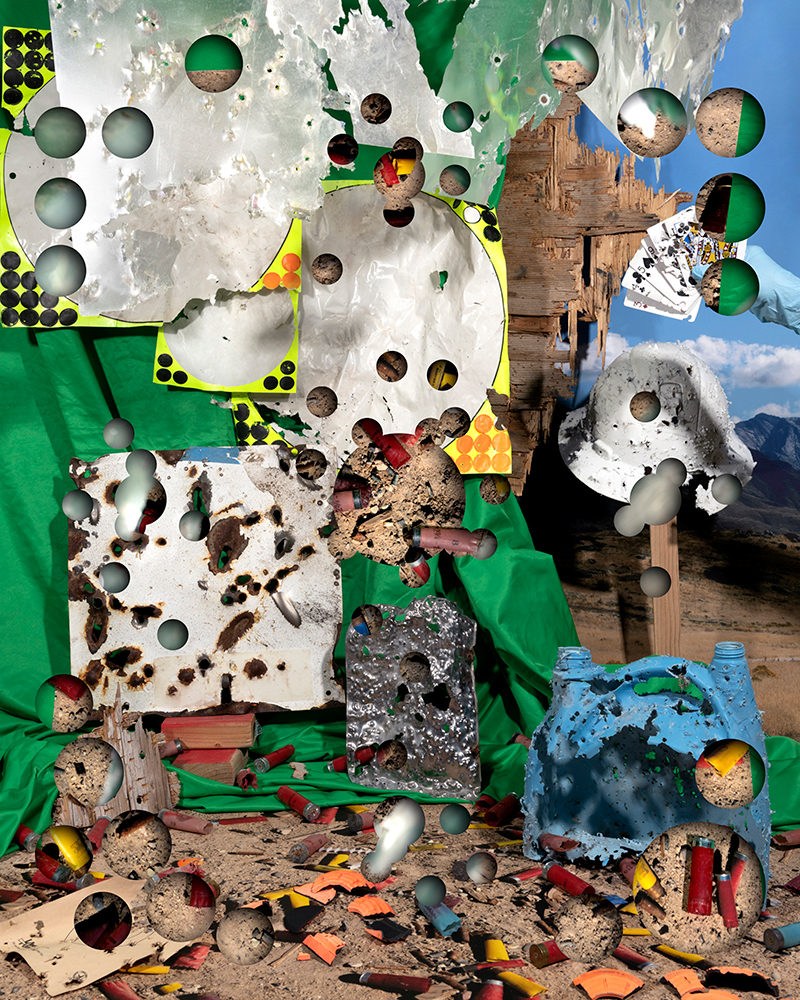

Marked combines traditional photographic techniques with contemporary digital processes, performance, and sculpture. The title refers to a prominent birthmark on my neck, which has drawn verbal and physical abuse from strangers. Reproductions of the birthmark’s shape and color appear throughout the work. In Marked, I consider ways we are marked from birth, specifically through gender. Birthmarks are like political boundaries on a map, expressing the desire to include and exclude, to mark belonging through exclusion and differentiation. The work explores the parallels between patriarchal attempts to subjugate and exploit the land and the body. This is visualized through the demarcation of the birthmark to represent what is through what isn’t.

The landscape and the body are tropes represented through photographic surveys, and both raise questions of power, representation, and ideology. The American West’s photographic surveys sought to document, aestheticize, and colonize the lands and the bodies viewed through the camera’s lens. Photographs of the landscape and the body still carry this trace of privilege and propaganda. Marked responds critically to this history by examining the fraught relationship between the land and the body and their abstraction by both patriarchy and photography.

Daniel George: You write that this project references the birthmark on your neck, and that its “shape and color appear throughout the work.” What got you thinking about centering your creative attention on this physical attribute of yours and making it a prominent visual component of your photographs?

Jaclyn Wright: I started working on Marked in late 2017, in the wake of the #MeToo movement. Although I’ve spoken about this work many times, I find I’m still hesitant to respond to questions specifically about my birthmark, partly because it’s deeply personal but also because I’ve trained myself to avoid victim-shaming by acknowledging my experiences. Due to my birthmark’s location, shape, and color, many people assume it is a hickey. This seemingly trivial mark provokes responses from strangers that fall on a spectrum that ranges from banal to verbally or even physically abusive, all of which are unsolicited and undesired. These experiences happen so regularly that they feel mundane at times. Before Marked, I didn’t have the emotional capacity or desire to make work about my birthmark. After the rise of Trumpism, neo-fascism, and its alarming rhetoric, specifically regarding violence against women, I couldn’t ignore it any longer. I try to use my birthmark in the work as a metaphor to speak more broadly to issues of violence, power, and trauma.

DG: I am interested in the connection you make between the landscape and the body through themes of “power, representation, and ideology.” Could you talk more about this link that you are exploring, and how they carry traces of privilege and propaganda?

JW: I began considering the connection between the landscape and the body after making the first few pieces in the series (Birthmark, I and Birthmark II (cut-out)). When viewed flat, I realized that my birthmark looked like a map. This directed my attention towards cartography and the role of borders/boundaries as a form of power and exclusion. These ideas were further brought into focus when I moved from Chicago to Salt Lake City in late 2018.

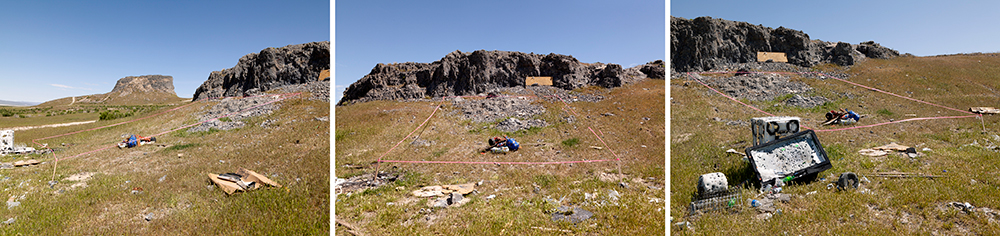

The landscape in Utah, and more broadly in the American West, is significantly different from the landscape around the Great Lakes. I was immediately drawn to the intensity of the landscape, specifically the West Desert located outside of Salt Lake City. The West Desert is managed by the Bureau of Land Management and is the ancestral homeland of the Goshute people. These lands are referred to as “public lands” and are theoretically free to use. However, significant acreage is leased to private extraction companies and cattle ranchers, both of whom cause severe ecological harm. Many sites in the West Desert are used for recreational target shooting. These sites echo with gunfire, and the landscape is littered with bullet holes and casings, large household appliances, and objects made of metal, glass, and plastic. The remnants of these objects are often left on site. My first encounter with one of these sites was eye-opening, and the more research I did, the more complicated this landscape became. For example, the US military controls vast swaths of the West Desert , including the Dugway Proving Grounds, used for testing biological and chemical weapons. These are just a few examples of the intersection of power, control, and exploitation of the landscape located between Salt Lake City and the border of Nevada.

I see the current use of the landscape as being intertwined with the history of those who inhabited it, colonized it, and continue to exploit it. For many, the desert is one of the last examples of the “frontier,” where one can act out their desires in the name of freedom. For instance, some individuals who shoot guns disregard fire conditions or leave large quantities of refuse behind. In my view, these actions exemplify an attitude of entitlement that can be linked back to the ideology of Manifest Destiny. I see this as a form of power over the landscape that parallels the subjugation of the gendered body. This parallel is further exemplified in the absurdity of supporting unchecked expansion of gun ownership “rights,” while denying women basic reproductive rights.

In terms of propaganda, photography has been used as a form of propaganda since its inception. Ranging from images of the transcontinental railroad, used to encourage westward expansion, to “scientific” portraits taken to support eugenics. I am interested in photography because it is not a self-contained medium but rather a medium whose social meanings are multiple and diverse. These meanings are not ahistorical, and their impact on contemporary photography is still visible.

DG: Your images also include elements of gun culture (i.e. discarded targets, shooting sites, etc.). For me, these details are also distinctly “American West,” and carry strong undertones when viewed with images of land and body. What other concerns are you addressing with these items?

JW: I agree that these elements feel distinctly “American West.” Before living out west, I had never encountered anything quite like these shooting sites. Initially, I was surprised at the ease with which people could access, openly carry, and shoot assault rifles but I don’t see this as the crux of the work. These elements are being used as a visualization of ideologies. When I look around these sites, I can’t help but see the mythology of the American West as perpetuated by Hollywood Westerns. These films use narratives about good guys vs. bad guys, where the portrayal of brutalities can be taken to celebrate that “progress” and “civilization” have rescued the world from injustices.

My point being, the targets are used to represent violence and the privileges inherent in these actions. I see the targets as a greater representation of the various impacts on the landscape, ranging from target shooting to the US military’s biological and chemical testing sites, all of which impact those who inhabit the surrounding region. In my view, this circles back to how I’m thinking about borders/boundaries and how they are used to include and exclude or mark belonging through exclusion.

DG: Tell us more about your interest in combining photographic techniques with that of performance and sculpture. What draws you to this sort of multifaceted process?

JW: I have never been a photographer who could go out and photograph the world as it is. For whatever reason, going out and “shooting” never compelled me to make work. As a result, I have tried many different photographic methods and have found that performance and installation (or sculpture) are my primary points of interest. I enjoy working with tangible things, that’s why my analog images are often exhibited traditionally, and my digital images are displayed as sculptures or installations. I’m certainly not anti-digital or anti-tech, but I enjoy the particular type of problem-solving that comes with the physical.

DG: In both your photographs and writing, you reference the history of photography and traditions related to the landscape and pictures of people. How do you feel your images broaden and contribute to that conversation?

JW: I can’t say whether the works successfully broaden the conversation, but my goal is to examine these histories critically. One of the things that I find most compelling about photography is its difficulty. The history of photography is relatively short but includes many examples that demonstrate its power, complicity, and accessibility (or lack thereof). This has considerable appeal to me. I feel that my work is critical of the history of landscape photography, a genre that has been dominated by white male photographers and has excluded female-identifying individuals and the imaging of their bodies. The intersection of the body and the landscape, specifically through performance, is not unique or innovative. Many artists have paved the way for this type of work—Judy Chicago, Ana Mendieta, and Laura Aguilar, for example. I am drawn to artists like this who have been direct and fearless in their perspectives, and motivated by their boldness. I hope that I can add something to the conversation by engaging with the complexity of the landscape and the history of photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026