Memory is a Verb: Rosalie Rosenthal: Midlife Tableaux

Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience brings together twelve women photographic artists exploring the liminal space between time and transience. Represented in this body of work are the universal concepts of loss, mortality, and legacy, and the exploration of what inspires us to seek solace, and reexamine our histories; subsequently unearthing discoveries about ourselves, our relationships, and our place in the universe. This week and next we are sharing projects from the exhibition with interviews by the artists. Today we feature the work of Rosalie Rosenthal who was interviewed by Elizabeth Bailey. Rosenthal’s artist talk will take place on Thursday, March 17, 5 pm PST through the Los Angeles Center of Photography. Her project, Midlife Tableaux explores the transience of objects and the weight of memory after the loss of a parent.

Memory, often regarded as fixed or reflective of reality, in this project actively functions as a transformative shape-shifter. The ongoing tension between two seeming opposites – objective fact and subjective perception – together shape a cohesive whole, creating something larger and more nuanced than just the sum of its parts. As new insight illuminates the past, this influences our experience of the present moment; which is itself slipping into the past at the instant we seek to define or quantify it. In this manner, time is elusive, elastic, bending back and over itself; perception comes full circle.

The project Memory is a Verb: Exploring Time and Transience began as the world was besieged with fear and anxiety during a pandemic, longing for a return to normalcy. Feeling a sense of loss, we craved connection to our past and to each other. The pandemic also offered a unique moment in which to interpret things differently. Beyond nostalgia, which selectively employs memory as a self-soothing balm, our exploration reconsidered how we view the past, and what is of purpose and significance, in light of our changed circumstances.

Rosalie Rosenthal is an artist who uses lens based and camera-less photography to investigate the transience of objects and place, and consider familial legacies transformed by context and perspective. Her practice looks beyond the intended purpose, or the expected vantage point, to cultivate nuance and possibility.

Rosenthal received a BFA from the University of Louisville’s Hite Art Institute and a BA in History from Smith College. She has exhibited nationally at the Griffin Museum of Photography; Filter Space Gallery, Chicago; the Los Angeles Center of Photography; Manifest Gallery, Cincinnati; Spaulding University and the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft.

Her photographs have been published in Fraction Magazine, aPhotoEditor and Manifest Gallery Photography Annuals. Her work is collected by 21c Museum Hotels, Omni Louisville, and private collectors. Residencies include Makers Circle in Marshall, NC and Residency Unlimited in Brooklyn, New York. Originally from St. Louis, Missouri, Rosenthal now lives in Louisville, Kentucky, where she works from her studio in the Portland neighborhood.

Follow Rosalie Rosenthal on Instragram: @rosalierosenthal

Follow Memory is a Verb on Instagram: @memory_is_a_verb

Midlife Tableaux

Midlife is traditionally a nexus for recalibration; parents reach an age of needing care, children become adults, and those of us in the middle assess and adapt. Midlife Tableaux is a manifestation of that reconsideration of self through examination of significant objects in my familial histories.

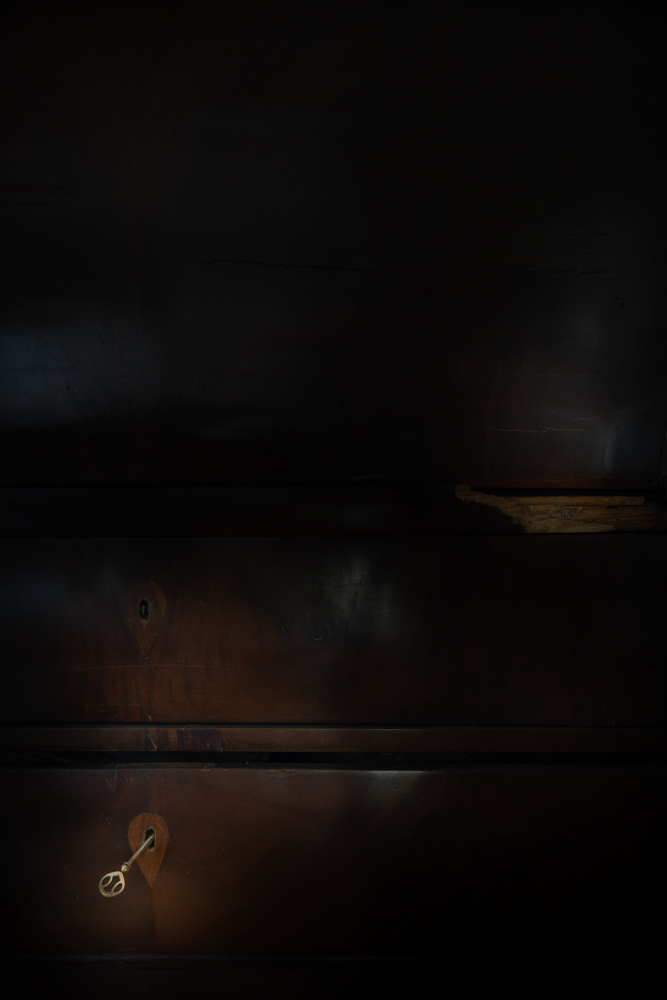

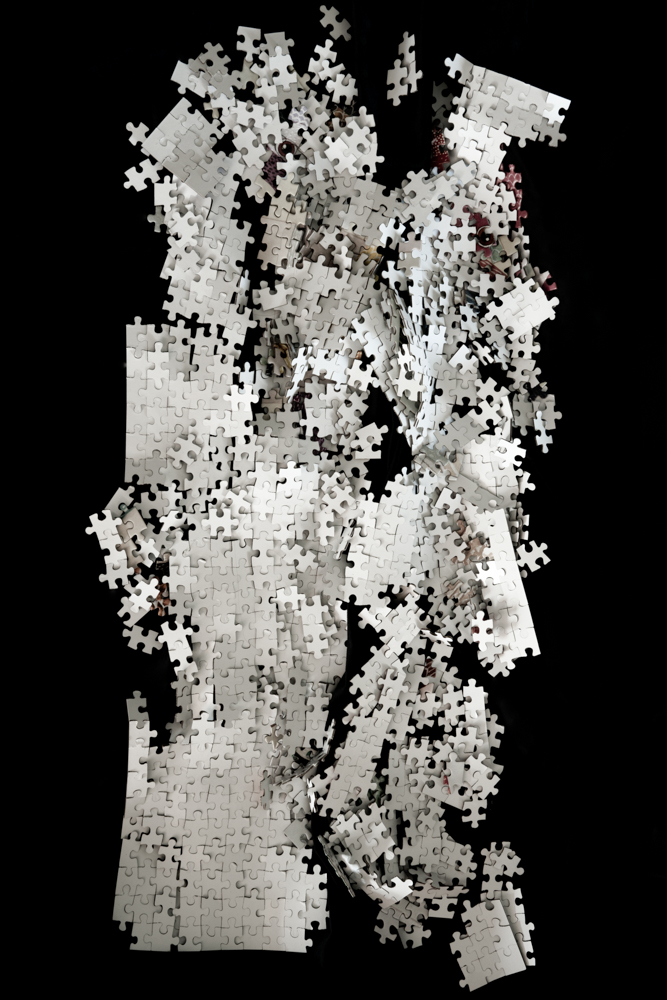

The project began after my father’s worsening Alzheimer’s disease prompted my parents to move from their home. Objects were packed-up, and many made their way to me. I photographed these objects as an act of care and as an expression of agency as I witnessed the intractable grip of memory loss. I choose the visual language of the still life and vanitas traditions to provide the historical context to explore mortality and to consider the significance of possessions, once resplendent, but now outdated.

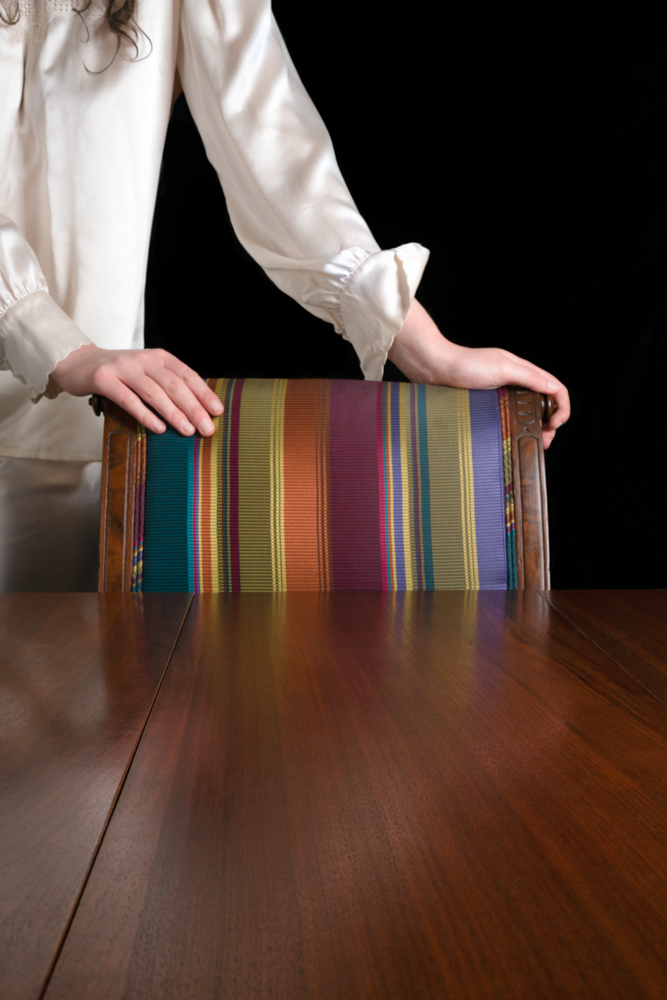

As my work progressed and the pandemic kept my family at home, I included myself and my daughter in the scenes. The intergenerational element allows the objects to become actors in a larger narrative about the gift and weight of a family legacy, both material and individual. Midlife Tableaux touches the human experiences of loss and transition and offers a respite for others to mine their interiority. -Rosalie Rosenthal

Elizabeth Bailey: What inspired you to create your project “Midlife Tableaux?” that is featured today in Lenscratch? Was this something you had been considering for a while?

Rosalie Rosenthal: At the time I began Midlife Tableaux, I was experiencing all the ways Alzheimer’s disease negatively impacts a family. I carried a sadness about my dad’s deteriorating memory, and the weight of responsibility for managing his affairs. But the catalyst that got me photographing was my parents’ move from their long-time home. When I unboxed the possessions that were given to me, I knew I would photograph them. I wanted to get a sense of the contents, and because composing a still life requires intensive looking, I knew the process would help me understand their meaning. Many items had been in storage for years, so photographing felt like a way of paying respect to belongings that had served past generations of my family.

Elizabeth Bailey: Your decision to create images with shallow depth of field, black backgrounds and lots of shadows is both striking and beautiful. What do these aesthetic choices represent for you?

Rosalie Rosenthal: I draw on the aesthetic conventions of Dutch still life painting with its use of shallow depth of field and dramatic lighting to focus attention and convey importance to my subject. The tableware I photograph has clear parallels with the still life genre and brings a historical framework. I also incorporate memento mori imagery— reflective surfaces, cut flowers—to reference mortality and the passing of time.

Elizabeth Bailey: In your dark, lush portraits and still life images, there is clearly a great deal of metaphor woven beneath their beautiful surfaces. For example, the shadows falling on your neck in “Ghost Mark,” belie something deeper than just the hanging pendant pictured. And in “Still Life with Trophy and Bulbs,” a classic, painterly composition is interrupted with light bulbs. Tell me about your use of metaphor in this series.

Rosalie Rosenthal: I feel that use of metaphor, rather than a documentary approach, makes the work’s themes of loss and legacy more accessible. Metaphor leaves space for other people’s experience and interpretation. With Ghost Mark, the viewer does not need to know why I made the image to feel the presence of a shadow or an imprint of some kind onto a person. That sensation becomes a point of departure for a viewer. In the still life you mention, the exhausted light bulbs act as contemporary memento mori. The juxtaposition of old and new imagery creates a contemporary access point to a time-honored floral motif.

Elizabeth Bailey: As you photographed these visible pieces of your family history, did your attitude and feelings change- toward either the objects, or the history itself?

Rosalie Rosenthal: I noticed an internal shift as I worked. I believe the act of photographing—spending time with objects and considering family and legacy in a quiet, focused way—put some psychological space between my emotions and difficult circumstances that allowed me to work through my grief.

The project also underscored the role of objects in recalling memories. I appreciate that I have tangible relics from some branches of my family tree. Many hold up well because they are intrinsically beautiful, others are poignant because of stories attached to them, and I will try to preserve their significance for my children.

I felt the fragility of memory. Some belongings have already lost their histories; others are on the verge of losing meaning. I recently looked through my great-aunt’s photo album. Alice was so lively and played such a significant role in my childhood, but looking at her pictures, I lamented that soon no one alive will share a personal connection with her. Such is the transience of time. As an artist, I hope to create something new from her album that will carry her essence forward.

Elizabeth Bailey: Your daughter appears in several of the pieces, and I am wondering how she feels about her family history and heirlooms, and/or her involvement in this work.

Rosalie Rosenthal: She is curious about the objects and interested in family history, and her openness comes through in the photographs. Luckily for me, she understood the significance of her contribution in making the project multigenerational. Her keen eye contributed to the success of the photographs, intuitively choosing the style and color of clothing to wear. She believes inherited belongings should not live a precious isolation in basement boxes so she will enjoy the china and glassware as everyday dishes without getting hung up on dropping a piece.

Elizabeth Bailey: Has family, or family history, often been a subject in your work? What are you usually making art about?

Rosalie Rosenthal: My curiosity about family history began when my mother took me on genealogy road trips as a child. Motherhood and domestic spaces have also informed my work from its earliest stages, likely because I was immersed in raising my children when I began to study photography.

Familiar and time-worn materials are common elements in my work. They tap into my interest in familial and cultural legacies because their physical condition reveals evidence of passing time and human touch. I often photograph with the intention to decontextualize these objects and change the expected perspective for viewing them. By introducing visual uncertainty, I create an opening to convey new meaning.

Elizabeth Bailey: What are your plans for this body of work? What is next?

Rosalie Rosenthal: Several of the images from this project have exhibited in group shows, and I am working to exhibit the group of photographs in conversation with one another. I am looking forward to creating a gallery installation of the actual photographic mobile pictured in Family in Repose.

COVID’s devastating impact on our vulnerable, elderly population amplified the emotions I experienced while creating this body of work. The death of my father and his sister during the last two years has brought a sense of finality to the project. From the intensity of focusing on mortality, my creative impulse has pivoted to making photograms in cyanotype with my own household belongings. The process incorporates sun, air and open sky which suits me well at this moment in time.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026