The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Vicente Cayuela

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Vicente Cayuela. Cayuela was selected for his immersive project, Juvenilia, and in 2022 received a B.A. with Honors in Studio Arts: Sculpture and Digital Media from Brandeis University, Waltham, MA.

The Honorable Mention Winners receive: a $250 Cash Award and a Lenscratch T-shirt and Tote.

In Vicente Cayuela’s photograph, “Terrific Traditions,” we see a depiction of one of the most iconic emblems of youth—the birthday party. As kids, we dream about it 364 days of the year—planning and hoping for something spectacular. But as we get older, the novelty and excitement wear off. Vicente’s image of a gull atop an off-kilter cake visualizes a coming-of-age realization—of romanticization being replaced by brutal reality. The still-life series, Juvenilia, delves into themes associated with the process maturation from child to adult. Brightly-colored and well-constructed, these photographs consider the evolution of identity. Though unique to each of us, the experience is universal—it is sometimes terrific, and other times terrifying.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Allie Tsubota, Artist and winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize and Shawn Bush, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean interdisciplinary artist, cultural worker, and art-based researcher. His photographic practice consists of meticulously staged photographs and installations that address contemporary youth trends, material culture, and more recently, Chile’s water crisis and the environmental impact of transnational industries in Chilean rural communities.

His work has been exhibited and published nationally in New York, Boston, Atlanta, and Winchester, including at the Griffin Museum of Photography and the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery in the SoWa Design and Arts District, as well as in international magazines and literary journals based in Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

He holds a B.A. in Studio Art and is a Wien International Scholar at Brandeis University. In 2022, he received the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation. He lives and works in Catskill, New York, where he received a one-year research residency from the Thomas Cole National Historic Site.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Juvenilia

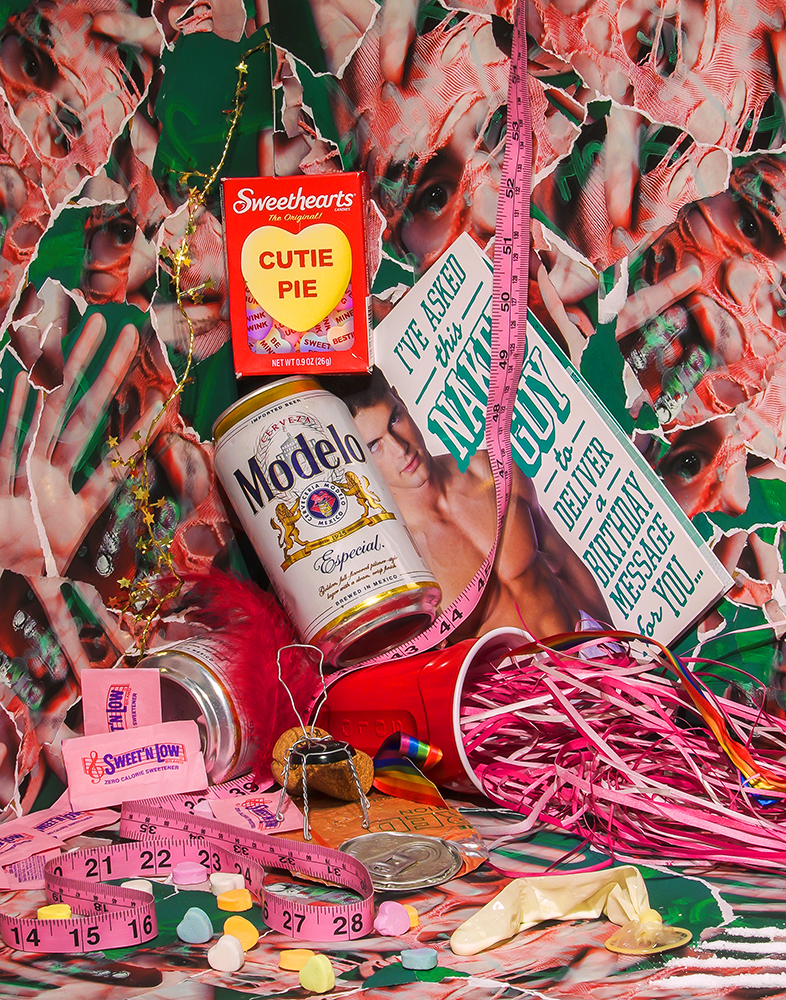

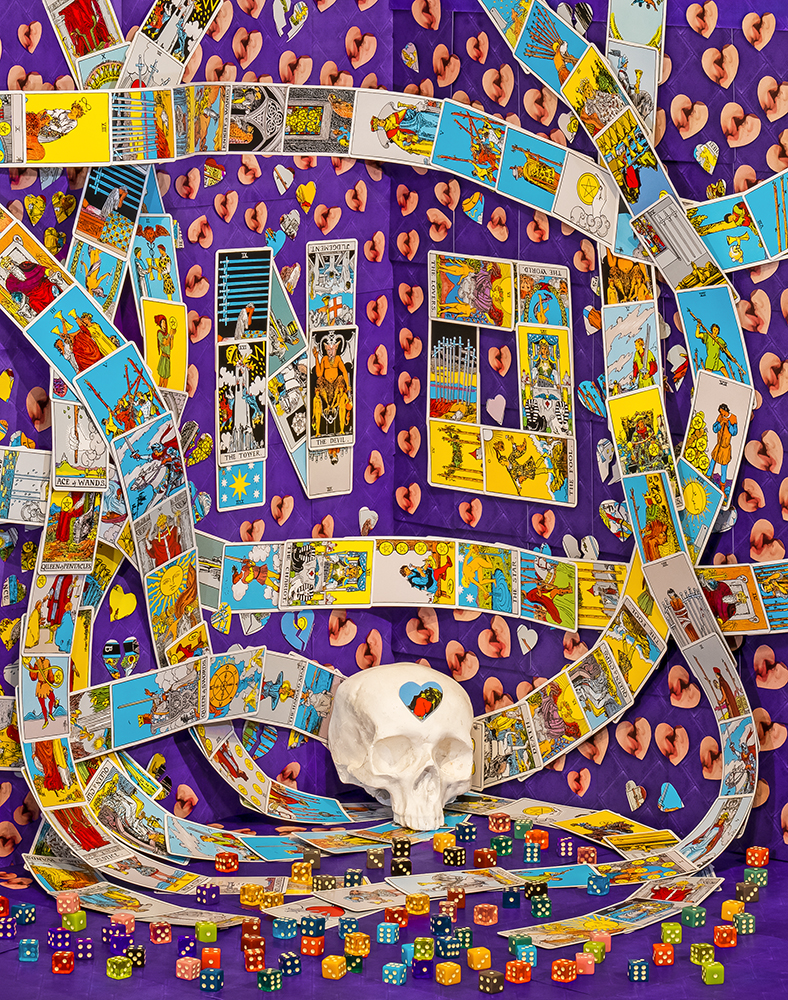

Juvenilia is a series of still lifes inspired by developmental trauma and romanticized notions of coming of age. Working at the intersections of collage, alternative photographic processes, set design, sculpture, and installation, I explore how photographs can be constructed to serve as a pathway to the regeneration of identity. Each photograph is a combination of graphic overload and visual bait, revealing narrative compositions that lie between the comic and the melancholic, the public and the autobiographical, youth and something vaguely defined as “maturity.”

By echoing the aesthetics of advertising and crowd-sourcing discarded artifacts from childhood, I seek to create modern allegories of youth, generational identifiers, and shrines of personal catharsis. By representing adolescence as synonymous with survival, these photographs embody the mechanisms I developed as a queer person to fit into mainstream society, and later discarded in search of inner freedom and individuality.

Beyond camp and sentimentality, Juvenilia portrays the fleeting but pivotal moments of early character formation that, however quickly they may pass, leave lasting marks on our developing psyche.

Congratulations on the honorable mention! To start off, tell us about your beginnings in photography. What brought you to the medium?

Thank you very much! I am so grateful for the support this project has received. I hope that in this way JUVENILIA can reach out to other young people who are struggling with their sense of self and offer them the opportunity for self-reflection, humor, and companionship.

My first camera was a shoot-and-go that my mom took on her travels and that eventually ended up in my hands. At the time, photography was about capturing memories. I never really realized its artistic potential until I took a class on the ethics of photography with Sheida Soleimani my junior year of college. It completely changed my perspective. I do not think there will ever be a time when I will not acknowledge the impact her work had on me. I had never seen anything like it. It was so meaningful, complex and critical, but also morbid, humorous, sacrilegious and irreverent. I became fascinated by other photographers who subverted the aesthetics of still life, tableau and advertising to make political commentary. The summer after, I decided I wanted to become a photographer. Since then, I have tried to immerse myself in the world of photography as much as possible. I had a late start, so I had a lot of catching up to do. I started looking for internships, making my way into galleries, and most importantly, surrounding myself with people who also had a passion for image making.

How about Juvenilia, specifically? When and how did that work start?

JUVENILIA was my undergraduate thesis in Studio Art and my first attempt at creating a photographic series. I was the only person in my cohort doing a senior thesis in photography. The only photography professor I knew had just gone on sabbatical and I was all alone with this very technical medium. So I decided to outsource and signed up for the Photography Atelier, a semester-long project development course at the Griffin Museum of Photography. In one of our sessions, we had to make a photograph that responded to a genre of our choice. I chose still life because I had been interested in constructed scenarios for some time. I picked up a bunch of trash after a college party and that’s how my first photograph (Barely Legal) came to be. I enjoyed working on that set so much that I knew immediately that I had found a medium that I could actually devote myself to. I continued to explore with this aesthetic and respond to youth and mental health issues more intentionally, which eventually led to the creation of JUVENILIA.

What interests you in utilizing collage/sculpture/installation?

Normally, when we think of photography, we think of a recording process that infallibly and accurately reproduces the truth. Photographs, however, have a quality that also makes them fantasy. They can be manipulated, altered, and staged. By taking an interdisciplinary approach, I can enter a space of artificiality that gives me more freedom and tools to create images that convey what I want to say. I like it when photographs are presented in alternative forms or coexist with other media. It makes it all the more immersive for me. Photographs can be woven, sewn, projected, printed on fabric, cups, and birthday cakes! There are so many possibilities when we think about how a photograph can exist in space, and this is something I want to explore further. I come from a family of carpenters and textile workers. One of my goals is to go back to Chile, learn some serious woodworking skills, and make photographic sculptures that engage with this materiality.

What kind of research did you do for this project?

Are late-night college dorm conversations field research? I think so. It’s oral history. I spent a lot of time talking to friends and acquaintances about their experiences growing up. I was particularly interested in other people and their feelings of failure, inadequacy, escapism, and lack of relationships. Alienation, from oneself and others, is a real problem that can span a lifetime and end in self-destructive behaviors. I have had friends and family members who transitioned into adulthood, lost any kind of protective social structure, and slipped right into alcoholism or became suicidal. Now we have a generation that feels so interpersonally adrift, an added layer of isolation across the globe, and an internet culture that is so cultish, that digital expressions of anger and alienation spill over into actual violence and self-harm. We need to have an open discussion about the causes and effects of isolation in society and offer real help to those who are affected by it. Pain and violence, both afflicted and felt, exist across the spectrum of human experience. Many of the objects in these photos I received from friends who were struggling with feelings of inadequacy. Others I found in the trash, as discarded artifacts from childhood. So it’s also a fieldwork of material culture and an ode to feeling obsolete and longing to find purpose.

One thing that drew me to your photographs was what you describe as the”comic and the melancholic.” They made me want to both laugh and feel pity. Tell us more about the significance of this sort of narrative.

Both the positive and negative aspects of growing up are so romanticized on social media. We act foolish on camera as an ode to youth, irreverence, and gleeful irresponsibility. We want others to know what a great time we are having. Life is fleeting and the responsibilities of adulthood are just around the corner. We want to look back at our Instagram archives and convince ourselves that our youth was idyllic and we did not waste it. But at the same time, having too much fun is paradoxical because the current game is as much about exploiting and monetizing trauma as it is about manufacturing perfect personae, filters, and masks from which you can also profit. We end up measuring our successes and hardships by our tails. We are simultaneously pitied, adored, reviled and cheered for putting pineapples on pizza 24/7. Andy Warhol said that everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. Right now it looks more like “everyone will subscribe to a lifelong personal streaming platform with unlimited storage capacity where we will share and criticize everything we and others do until we die to satisfy a chronically excessive need for dopamine, belligerence, and attention.” Connecting with others is an essential part of being human. We want to feel seen and we want others to share our happiness, just as we want them to empathize with our problems. Social media can provide a sense of connectedness as much as it can create a distorted and fractured sense of self that leads to further social alienation. These photographs vacillate between comedy and melancholy as they respond to this radical new form of virtual socialization and its effects on loneliness, authenticity, and self-perception. I thought that by addressing this phenomenon, I would also have the opportunity to criticize and poke fun at it, while drawing attention to the real issues young people face behind screens and theatrics.

You write that “Juvenilia portrays the fleeting but pivotal moments of early character formation that, however quickly they may pass, leave lasting marks on our developing psyche.” Could you talk about why you feel it is important to visualize these brief, yet consequential events?

I say fleeting because I often perceive the message that youth is ephemeral and to some degree inconsequential. It is easy to overlook certain actions and behaviors with the excuse that youth and its vices are meant to be transient and futile. However, repeated patterns of behavior can easily become deeply ingrained personality traits that are much more difficult to change. It is well known that our capacity to maintain interpersonal relationships, to love and trust others, that our relationships to sex, money, food, drugs, adversity, friendship, consumption, and death are shaped by the experiences of our youth. Growing up has a lot to do with forming those memories, and memories, for better or worse, are too fleeting and unreliable. I say this not to pretend I have it all figured out, but to try to understand something I struggle with constantly. I hope that JUVENILIA conveys the idea that even though the emotions and experiences of the past are still operative, we are not bound by the heavy chains of childhood that hold us down. We live in a continuum of growth and renewal.

I’d like to hear more about your educational experience. How did your creative practice evolve while you were in school?

In college, I took some sculpture classes and made some whimsical busts out of natural materials and paper pulp. However, I felt that my work was not complete until I took these little creatures out into nature and photographed them. So in a sense, I was always constructing scenarios for the camera. This manual process became the basis of my photographic practice. I enjoy the control that working on sets give me and the protective shield of being behind the lens. Soon after, I started collecting readymades and making props out of whatever I had on hand: Trash, leftover candy, found chairs, forks, Sweet n’ Low packets, bottles, scraps of wood, measuring tape. There was something playful about collecting these things in my everyday life that I really enjoyed. I remember one very restless night tearing up my pillows and coloring the filling with acrylic paint to make the fake cotton candy for “Sugar Crash.” Moments like that really helped me unleash my imagination in developing this series. I used to have a very narrow idea of what art could be. Now when I go for a walk, I see something that I think I can use for a photograph and I just pick it up. Making props, collecting objects and photographing them will always be a part of my practice. It helps me see the beauty in the little things that surround me.

Was there any advice that you received (in the form of a critique, or something else) that you feel had a significant impact on the trajectory of your work? Would you mind sharing?

One of the most useful criticisms I received was that I needed to be more delicate and careful with my sets. I had originally been working on woven paper sculptures for my thesis. People seemed to like the delicate work in those pieces, but I could not really relate to what I was doing. While my early work had a certain precision, I lost a lot of that when I started working on JUVENILIA. My sets were shabby and constantly falling apart, but I related to them a lot more and had a lot more fun too. Other times, I received a lot of criticism that I did not fully integrate. I was told my work was shallow, too flashy, too campy, too juvenile, etc. When I think about it, I have to laugh, because in a way, was not that the whole point? At the end of the day, you take what you get at the moment, and maybe in the future you’ll say, “I wish I had not been such a stubborn goat, because I totally understand what they were saying.” Or maybe you’ll be completely unapologetic, and that’s fine too. You can’t appeal to everyone. Sometimes I look at some of these photos and wish I had done some things differently, but I can live with that feeling. Being young (and being human) also means accepting that we are imperfect. I like that these photographs embody that growth. Juvenilia means both “compositions created in the artist’s or author’s youth” and “artistic or literary compositions suitable for or intended for the young.” This was my first body of work and I feel that I created something people can relate to, and that brings me a lot of satisfaction.

Being a student can be exhausting, and burnout is real. What motivates you to keep creating?

I have always liked to learn. Learning by doing is my main motivation.

To wrap things up, is there a mentor that you’d like to acknowledge?

I am deeply in debt to Mark Dellelo, my boss at Brandeis Sound and Image Media Studios. He was my first mentor and gave me so much support. At the media lab, I was surrounded by an amazing group of creative people who inspired me to pursue my artistic passions. That place will always mean a lot to me. It’s crucial to have a community of people cheering each other on, especially in fields where it’s so hard to get your foot in the door. You are much more encouraged to keep going when you have this kind of environment. There is also Joe Wardwell and Catherine della Lucia, who mentored me during my senior thesis; the Fine Arts faculty at Brandeis, lauren woods, Tori Fair, Sheida Soleimani; Elizabeth Buckley, Crista Dix, and Paula Tognarelli at the Griffin Museum of Photography, who championed my work; Brenda Paz Soldan, for giving me a second chance; Theo Brandt for the all-nighters in my studio; and Robert Lozniceru for his support and friendship. Without him, many of these sets could not have been completed in time. And finally, my family, who still have no idea what I am doing with my life, but support me anyway.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Mackenzie CalleJuly 31st, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Seok-Woo SongJuly 30th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Vicente CayuelaJuly 29th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Daniel HojnackiJuly 28th, 2022

-

The 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place Winner: Alana PerinoJuly 27th, 2022