Photographers on Photographers: Seth Adam Cook in Conversation with Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison

When Aline Smithson invited me back for another Photographers on Photographers interview, I knew I wanted to continue reaching out to artists whose work made an unforgettable impact on me early on. In this case, I was an undergraduate student who had just decided to pursue photography. My professor reviewed our next assignment and showed the class a book as an introduction to storytelling and performance. The book was called The Architect’s Brother by Shana and Robert ParkeHarrison, and it forever changed my perspective on photography – not just because of the content, but the context of their work. They inspired me to pursue photography as an effort to combine art with meaning and always to ask why when thinking about the possibilities of the photographic process. Their work opened my imagination, so I thought this was the perfect opportunity to reach out to them and finally connect with a pair of genuinely inspiring artists.

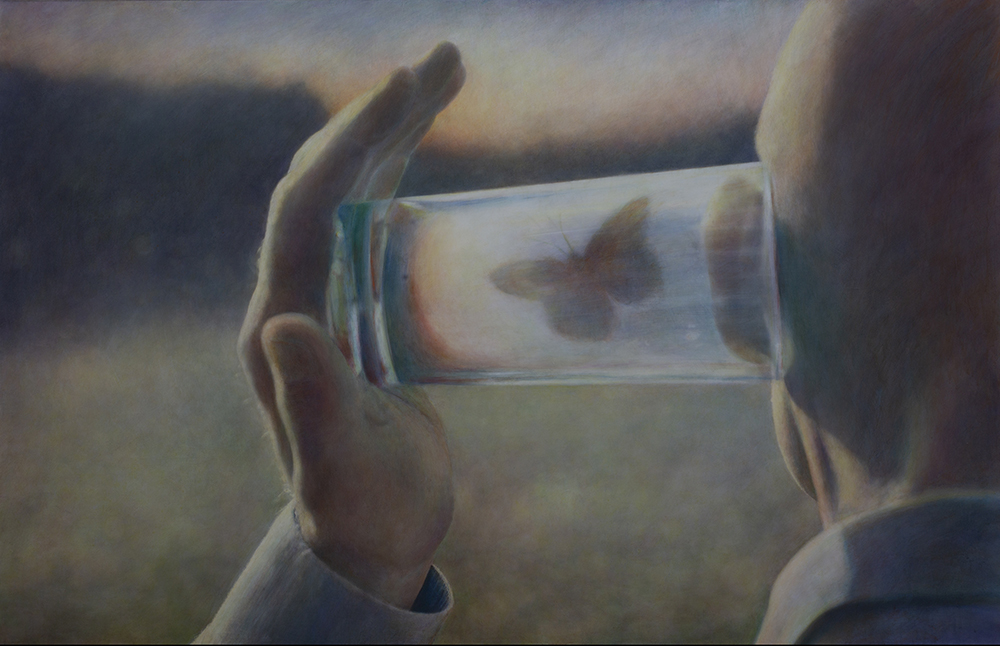

The ParkeHarrisons construct fantasies in the guise of environmental performances for the protagonists of their images. The artists combine elaborate sets within vast landscapes to address issues surrounding man’s relationship to the earth and technology while additionally delving into the human condition.

The ParkeHarrisons’ collaboration has developed organically over the past 30 years. In 2000 they began to publicly claim co-authorship of their images.

Their works are included in numerous collections including Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Art Institute of Chicago and Mudam Luxembourg – MusÉe d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Kansas City, and Galerie im Stadtmuseum, Jena, Germany. They have exhibited in over 45 solo exhibitions and over 100 group exhibitions and festivals including: Festival La Gacilly/Baden Photo, Lille 3000/Fantastique!, Mediations Biennale, MONDES INVENTÉS, MONDES HABITÉS,Angkor Photo Festival, The Missing Peace: Artists Consider The Dalai Lama and Imaging a Shattering Earth.

They have two monographs published by Twin Palms Publishers, The Architect’s Brother and Counterpoint.

Follow the ParkeHarrisons on Instagram: @parkeharrison_studio

We are at the precipice of what could become the long and painful road to extinction. What sets us apart from other inhabitants of this beautiful planet is that we have a choice. We can choose to change. We can choose to stop this destruction. We have ingenuity. This ability allows us to dream of better worlds, to invent solutions. But we must choose to invent wisely, imagine in smarter, sustainable ways, not just for ourselves, but for the planet and all of its inhabitants. As artists we choose to harness hope to encourage change on a significant scale.

Our understanding of this coming reality coincided with our realization that our Art must speak to viewers in a meaningful, soulful way. In the early 1990’s as we studied the ideas of Josef Beuys’ social sculpture, our emerging purpose for our Art began to form. We determined our Art would speak to change, to influencing viewers toward visceral, sustained contemplation of their own place in our evolving existence. Our work explores the complex relationship linking humans, nature and technology. Within each body of work this triangular narrative ebbs and flows. We use this loose narrative as a means to communicate with viewers about our collective fate and our shared ability to create positive change.

Our photographs offer visual poems of loss, human struggle, and personal exploration within landscapes scarred by technology and over-use. As collaborative artists, we strive to metaphorically and poetically link laborious actions, idiosyncratic rituals and strangely crude machines into tales about our contemporary experiences. We construct elaborate sets made from found objects. Our scenes combine real and constructed landscapes. These scenes have a sense of determination and irony while addressing mankind’s responsibility to heal the damage inflicted on the environment.

Staged images offer endless possibilities for exploration while offering viewers personal interpretation. By allowing viewers to complete the story before them, we allow agency to take hold within them. We develop layers of duality: hope and despair, success and failure, desire and distain, destruction and stewardship. We explore the fragile human condition, and the overarching shadow of environmental destruction. Perhaps the only true hope for our world and our human spirit rests in our ability to imagine. – Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison,

Seth Adam Cook: Thank you, Shana and Robert, for taking the time for this interview. I was curious if you could first talk about what brought about your collaboration and how the two of you discovered your shared vision?

Shana ParkeHarrison: Wonderful to make your acquaintance. We looked at your work last night, very nice. It seems we share an affinity for infusing meaning within the use of materials/techniques!

Our shared vision has evolved over a long period of time. As a couple we began to combine our individual interests, skills, attributes and energy in the early 1990’s while in graduate school at the University of New Mexico.

We were there together but with separate pursuits. We discussed our ideas and often acted as assistants to one another when necessary. As we grew as creators our agendas began to meld, and became more complex and nuanced as a result of our differing points of view. After leaving UNM we spent a year at the Roswell Artist in Residence. There our collaboration really began to take shape and we began questioning the idea of creating as solitary artists. The body of work required two creators with its distillation of ideas, research, prop building, on site photographic gymnastics, darkroom work, mounting of large-scale images onto panels and painting to complete these works. Over the next several years and several bodies of work we continued to question/investigate the process of collaboration. Around 1999 it was clear to us that our working relationship was essential to the creation of the work.

It was as though there were three people in the room: the two of us and the work. Essentially the work decided we needed to collaborate. The complexity of the work required two people.

Seth: So what was it about photography that drew you to utilize it as your primary method of visual communication?

SPH: We each intended to be painters. I (Shana) have a BFA in painting. Bob intended to study painting as well. He attended the Kansas City Art Institute. The first-year program forces students out of their preconceived notions. Bob took a class in pinhole camera and it blew his world wide open. For both of us the allure of photography is within its perceived reality. We love creating worlds that are certainly not real, but are believable. The way photo allows us to construct realities aligns with our painting instincts. Our images result from research into multiple interests, which then evolve into drawings, then prop creation, photo experimentation, reworking of ideas at every level, and eventual photos that are then combined with other photos (either through paper negatives in the darkroom or within photoshop). As you can see from this brief description, the decisive moment, is NOT what drew us into photography!

Seth: I can definitely understand. This actually brings me to my next question, regarding your work during and after graduate school. I was wondering if you could elaborate on what it was about your surrounding environment that inspired the series The Architect’s Brother? I know that the surrounding New Mexican environment had an important role. Still, I wondered if there were any particular events, discussions, or ‘eye-opening’ moments that drew you to speak about the environment.

SPH: Bob’s graduate advisor, Tom Barrow, once said to us, “This landscape will change you.” He was so right! When we started grad school, we were just a couple of suburban kids, who had no idea the environment was experiencing stress, let alone catastrophic destruction. As we fell in love with the barren landscape of the Southwest, we began studying the relationship of native cultures to the land. The Book of Hopi was and still is quite inspirational to us. As we learned more about the environment, we became aware of the US military’s destructive practices in New Mexico: Los Alamos National Labs, and Trinity Site are prime examples. Our environmental awakening came at a time when we were each questioning our own detachment from the natural world. This combined with the emergence of multi-culturalism in the arts. So the raw, tenuous landscape of New Mexico, its destruction at the hands of its colonizers, and the realization that much of the responsibility for the technological advances that fueled environmental decay fall to white males, led to the work known as The Architect’s Brother. As you may know this work investigates mankind’s relationship to the natural world. It questions our individual and collective actions, it questions the underpinnings of cultural, political, technological and religious systems and the effects of these systems on nature. We chose to create a world that allows viewers to contemplate these ideas through the actions of a single individual. This protagonist interacts with nature through rituals and experiments.

Seth: Your mentioning of the Architect’s Brother leads me to my next question, that being Robert’s character known as the ‘Protagonist.’ This persona you and Robert created has been a mainstay throughout your career, and he and the mythos you created continue to exist. Why?

SPH: Over many years we developed the character in our images. We refer to him as the Protagonist. We were/are both interested in theater, and the ability of characters to convey meaning. Likewise, we liked the idea of using a character that prompted a viewer to see themselves within the image. This idea of making the viewer proactive in their engagement with art refers to our interest in Brecht’s theories on audience participation as well as Beuys’ theories on social sculpture. In both cases viewers are called to be active in the process of engaging in art and active beyond that engagement. By using the same character continually questions surrounding the character himself fall away, and he becomes a stand in for humanity: his individuality is neutralized through repetition. Finally, Robert has always been interested in performance. He likes the cathartic aspect of being active in the images.

Seth: After the Architect’s Brother, other bodies of work, such as Counterpoint Grey Dawn and Gautier’s Dream, other figures reside within the same world as ‘the Every Man.’ The symbolic representation of the Every Man has me curious about who these other characters are and how they relate to your main protagonist. What encouraged the exploration of other figures?

SPH: When we stopped making the Architect’s Brother, we assessed many aspects of that work as we began making Gray Dawn, then Counterpoint. We changed our approach to composition, obviously color, and we changed the tone of his character. He was no longer the protagonist/centered/heroic/idiosyncratic. In the Gray Dawn and Counterpoint work we see him as less proactive. In fact we see nature as the protagonist: speeding and morphing in unexpected ways. Robert views/reacts and in some cases is the victim of nature’s force. Further, he sometimes acts a destroyer/ instigator. In this work, other figures begin to emerge. This is a small number of recurring characters. Namely, our daughter, who continues to engage in our process from time to time. We wanted to be less rigid in the casting/meaning. As such we wanted to explore how other characters could inhabit this new world. While we wanted there to be a link to our previous work, we also wanted these images to broaden the worlds we create.

Seth: They don’t appear in later bodies of work, where the Every Man is seen again as the sole figure in the environment. Why is that?

SPH: Our vocabulary ebbs and flows. Sometimes this is intentional other times it is opportunity. We have worked with large groups of dancers over the last ten years, for live performance as well as video. (This work is not on our website) Some series were created in the dead of winter, when we were be hesitant to involve others in the discomfort of making images in the cold, thus the singular character returns. Other times we have used people because we were at residencies. At this point we try to go with the flow/opportunities before us.

Seth: Since we are on the topic of your other bodies of work, I wanted to branch off for a minute and ask a specific question related to the series Acts without Words. At first, I thought I was looking at pastel drawings and needed to look closer at a few of your images to recognize the photograph within. I find this body of work one of your most stunning, and for me, it stands out from the rest. I was wondering if you could talk about your approach to the project and why you chose this process.

SPH: There has always been a balance/tension in our work between photography, constructed photography (darkroom/or photoshop) sculpture, set building, real landscapes, and painting. Most of our work including The Architect’s Brother is finished with painting and UV Varnish. Each series is different. Architect’s Brother used many layers of colored or clear glazes of paint to create an Encaustic quality, while concealing flaws from the paper negative process. In Gray Dawn/Counterpoint we used paint to heighten, enhance the color limitations of archival printing. In Precipice we embedded the layers of painting be creating textured watercolors, photographing them and then using the image file of texture as a layer within photoshop to breakdown the clarity of the digitally produced images. In this work the breakdown through layers acted as both paint and as paper negative like our early darkroom work (Architect’s Brother).

And so, for Acts without Words we wanted to make the work more painterly, thus pressing the pendulum in favor of paint. We wanted to explore the luscious capacity of paint as an enhancement to the imagery. And while it is difficult to experience the painterly quality of these works through jpegs, these works are quite beautiful and they certainly make the viewer question what exact mediums are present.

Seth: Something about the images in Acts without Words resonates differently than in previous projects. There is a bleakness to the imagery, an almost suffocation and distress, contrasted with the surfaces bright colored paint. The Protagonist and the viewer could be standing in the same space, engaging with each other, whereas before, the viewer was but a spectator. Everyone reads into work differently, but I wondered what brought about the direction for this series? Am I right about my feelings towards the series, or is it simply my interpretation?

SPH: Interesting. To answer you last question first, the viewer is never wrong. As you know as a creator, there is no right way to interpret a work of art. We are always thrilled to hear differing ideas on what people see in an image. We see these images as melancholic for certain. Likewise, they exhibit the light quality of northern renaissance painters…. A quality that has been an inspiration in our work since the very beginning.

As I mentioned before, these images focus on the physicality of painting to a greater extent than previous bodies of work.

Seth: Thank you for your response. As someone who is also interested in infusing work with process and meaning, I was curious to hear why you and Robert continue exploring your concepts with alternative photographic processes? Each project discussed carries its own process, but what about the process piques your and Robert’s curiosity? What does it add to your conceptual concern?

SPH: As you likely have experienced, working in a process-oriented way allows one to ponder the meaning of a work, and thus to develop the language of materials/content, to create work that can be more immersive to the viewer. At this point we don’t exactly consider our work to be of the alternative photographic process classification, at least not in that old school, glass plate, chemical alteration way of working. But we clearly feel the need to complete a photographic image, to bring it to another place through intervening with its initial pure state whether that is through paint or through creating unique manipulation processes in photoshop.

Seth: I couldn’t agree more. I wanted to branch away (again) and ask you something different about your careers. I am recently starting a new job in teaching, and it got me curious to hear about your approach to teaching and what aspect of education you find the most rewarding. What do you tell your students about reaching out to people in this industry and getting their work out?

RPH: For me the most rewarding aspect is when students evolve into their own creative selves. When they take the technical knowledge they have gained and begin to trust their instincts. I focus on helping those students to find opportunities in the summers and beyond graduation. Often this is not a conversation about breaking into the art world. Rather I recommend residencies, workshops, personal development outside of the school structure followed by professional opportunities or grad school. I feel that jumping to the conversation of ‘the industry’ and getting their work out there and making money, is counterproductive to young artists who have only just started to understand the personal development and fulfillment they may receive from making art. The industry will chew them up and spit them out if they jump in before they are fully grounded in their practice.

Seth: I couldn’t agree more. It is also inspiring to see students begin finding their way. What advice would you have for photographers struggling to pursue projects with fresh eyes?

S&RPH: Go to the library. Go to live theater and dance. See LOTS of arthouse films. Journal. Open yourself to the possibility of saying what if?

Seth: Thank you both again for being a part of this interview. One last question I have is, of course, what is next for the ParkeHarrisons?

PH: We are extremely excited to be returning to the darkroom… after a very, very long time. Much of our work over the last 12 years has been digital or shot analog but printed through a lab. We look forward to more experimentation and those mysterious and happy accidents of the darkroom.

Seth Adam Cook is an artist from the Bayou Teche region of south-central Louisiana. He utilizes the swamps and marshes of his home as a point of departure for his versatile studio practice. Cook holds a B.F.A. in studio art from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and an M.F.A. in photography from Indiana University, Bloomington. In 2021, he was awarded ‘Juror’s Selection’ from the New York Center for Photographic Art for his alternative process photography. In 2020, he was named one of Lenscratch’s ‘Top 25 to Watch.’ Also, in 2020, he accepted a ten-month residency with Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center in Cincinnati, OH, where he worked and taught as their ‘Scholar in Residence.’ His work has been displayed nationally and internationally, including in South Korea, Louisiana, New York, California, Colorado, and Massachusetts.

Follow Seth Adam Cook on Instagram: @s.adamcook.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025