Photographers on Photographers: Helen Jones in Conversation with Barbara Bosworth

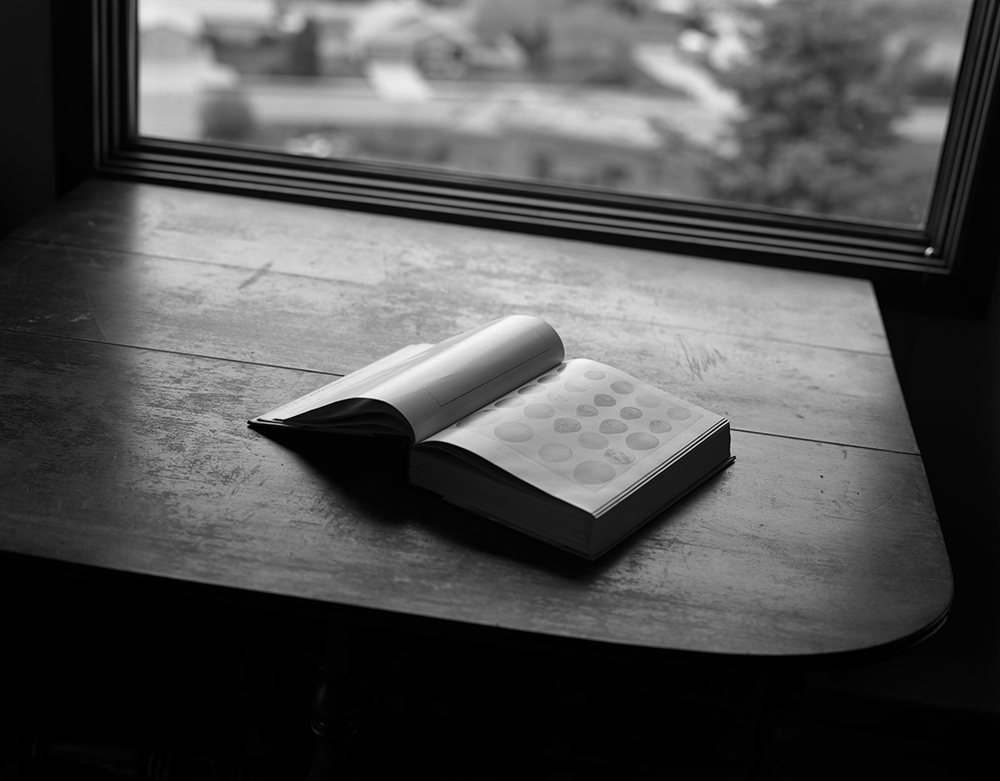

©Barbara Bosworth, Hounds at tree, Lochsa River Valley, 1992, from “One Star and a Dark Voyage” published by TIS Books

I met Barbara Bosworth while studying photography at the Massachusetts College of Art. Her classes were inspiring and memorable, as are her large format photographs. Her images approach the world with a quiet wonder. They encourage what Barbara would call ‘slow looking’ and celebrate the natural world without extracting it from everyday life. Barbara has had a long career in photography and has made many beautiful books, ranging from extensive monographs to small runs of unique self-published booklets. Books are so often the way that I encounter photography, they can be easier to come across when you don’t live in a big city, and they allow you to sit with the work for an extended time. When asked to interview someone for the Photographers on Photographers series, I knew I wanted to talk with someone whose photographs I admired and who also worked with books. I immediately thought of Barbara. I am so grateful to have had this opportunity to learn a little more about her long-term photographic practice, inspirations, and interest in bookmaking.

Barbara Bosworth is a photographer whose large-format images explore both overt and subtle relationships between humans and the rest of the natural world. Whether chronicling the efforts of hunters or bird banders or evoking the seasonal changes that transform mountains and meadows, Bosworth’s caring attention to the world around her results in images that similarly inspire viewers to look closely.

Bosworth grew up in Novelty, Ohio. She currently lives in Massachusetts, where she is a professor emeritus of photography at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston. Over her long career, Bosworth has photographed in both black and white and color. Her single images display a generous attention to small facts, while her large-scale triptychs reveal a panoramic awareness, one that lets viewers glimpse relationships between frames across a wide field. While all of Bosworth’s projects remind viewers not only that we shape the rest of nature but that it also shapes us.

Bosworth’s work has been widely exhibited, notably in recent retrospectives at the Denver Art Museum in Colorado, Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona. Her publications include, The Heavens (Radius Books, 2018), The Meadow (Radius Books, 2015), Natural Histories (Radius Books, 2013), Trees: National Champions (MIT Press; Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 2005) and Chasing the Light (Nightwood Press, 2002).

Follow Barbara Bosworth on Instagram: @barbarabosworthstudio

©Barbara Bosworth, The crescent moon, (3 days off new), June 15, 2010, from “The Heavens” published by Radius Books

Helen Jones: Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed! You work with a large 8×10 film camera, which leads to a slow and meditative photo-making process. Long exposures like these are rendered in a specific way that, I think, is quite beautiful. I am thinking of a photograph you have (one I particularly like) of a group of dogs surrounding a tree in various states of blurriness as they chase their prey or your pictures of the moon and stars streaking through the sky. Can you tell us what you like about photographing like this?

Barbara Bosworth: Hi Helen! Thanks for asking me to be part of this interview series.

I consider photography to be “a long look.” The characteristics of the 8×10 camera allow me to take time to really look closely. The subjects I’m drawn to often reveal themselves over a longer period of time, quietly, so the camera I use is a good fit for my interests.

HJ: I wonder if this slow way of working also extends to bodies of work. How long do you work on projects? Do you keep several going at once? How do you know when one is finished?

BB: I photograph what I’m drawn to, rather than working on a predetermined project. It’s often only after decades of making photographs that I begin to edit the work into books.

Many of the images throughout my books are made concurrently, overlapping in time.

My interest in a subject continues after a book is released, so the work goes on and on. Though The Sea was just released, I still love photographing along the shore.

HJ: Can you talk a little more about The Sea?

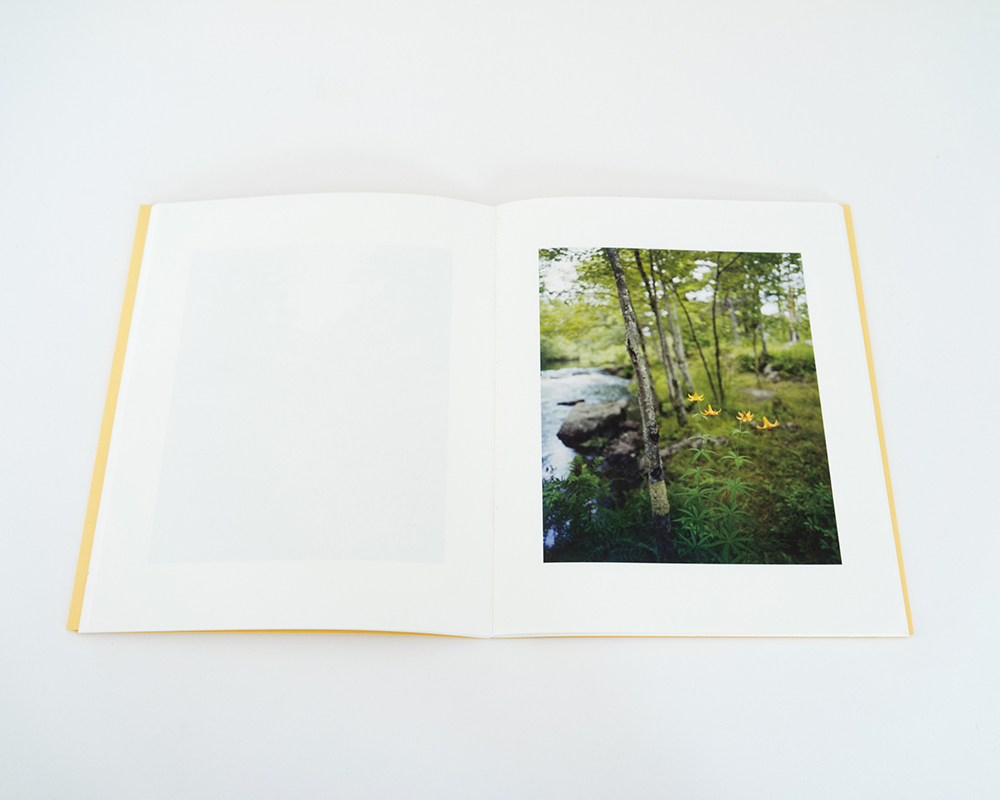

BB: I love looking at the sea. I’ve photographed it for over four decades. Every photograph is different, even when they’re made minutes apart. The sea is constantly transforming, shapeshifting the water, air, and land around me. The atmosphere moves. I can’t stop looking once I’m out there with my camera. My newest book The Sea is an homage to the experience of being at the shoreline. The sea is a terrifying but beautiful place.

HJ: Your work seems to be all about wonder and connection to the natural world. Many of your projects look extensively at one element—The Meadow, The Heavens, The Sea. Have you always worked this way? Why are these topics important to you?

BB: These broader ideas allow me to dig into a myriad of fascinating topics. They set the stage for conversations about natural history, art history, personal stories, and photographic experiences of the natural world. For example, Natural Histories allowed me to tell stories of my family in relation to the natural history of my childhood places. Through the photographs, I looked at shell and bird egg collections, botanical studies, and family traditions.

HJ: Was your family particularly interested in natural history? Where did you grow up, and did it influence your image-making? Can you talk about how your own autobiography makes it into your work? I think it can feel tricky as an artist to intertwine the personal with broader topics, but I also think work that does this is lasting and authentic. How do you make it work?

BB: Natural Histories was about the generations of my family’s interest in natural history. I grew up with an English grandfather who took me on long walks through the woods of Ohio. He used a handmade walking stick, and would use it to point out wildflowers, trees, and variations of the seasons.

My father was similarly drawn to the landscape. He loved observing the natural world. I would often join him on walks, looking out at the sea in Cape Cod, or at a sky full of stars. He could stare forever, looking at clouds moving across the sky.

The work I make is about my life. An audience may see their own lives reflected in the photographs, childlike curiosity about nature, generational connections to the land, and wonder of the natural world.

©Barbara Bosworth, My father showing me the junonia, Sanibel, 1995, from “Natural Histories” published by Radius Books

HJ: What brought you to photography? Did you dip your toe into other mediums first?

BB: In the late 70’s, friends in the Cornell Physics Department allowed me access to their lab’s darkrooms. It was there, afterhours, that I learned how to print photographs. At the same time, I was working in the Cornell Department of Rare Books where I had the opportunity to see amazing books. The interplay of books and photographs started my path as a photographer, and stays with me.

HJ: That sounds like an incredible place to work. What were a couple of your favorites? I am thinking some of these books may have made it into your future projects in some way?

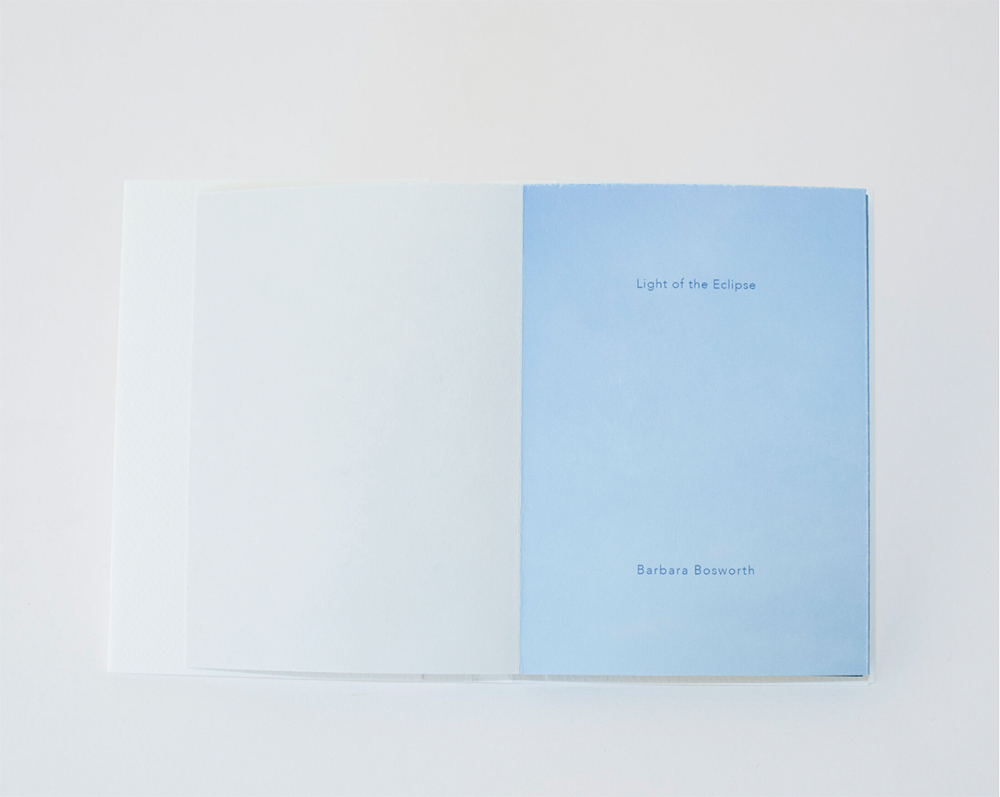

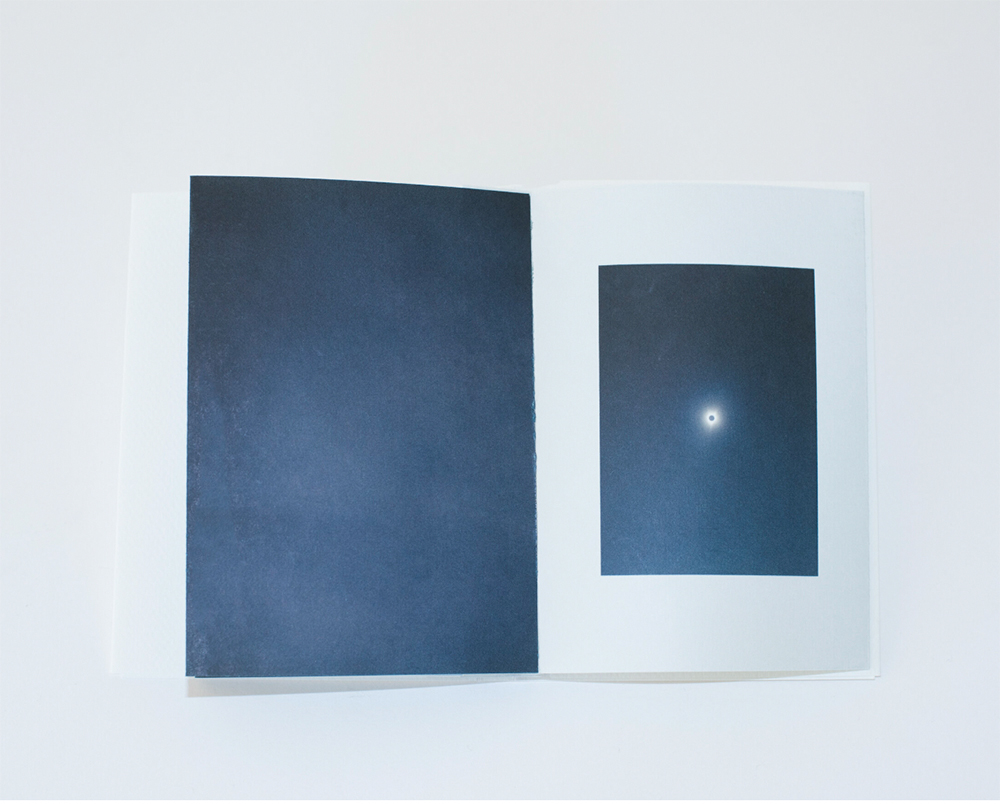

BB: While working at the library, I had access to Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius. I’ve always held the illustrations from this book in my mind – small pencil sketches of the sun, stars, and moon by Galileo himself. In my book, The Heavens, published by Radius Books, I photographically recreated these drawings, and printed them in the style that would have been commonly used in bookbinding at the time Sidereus Nuncius was published in 1610.

HJ: At times you have collaborated (with Margot Anne Kelley for The Meadow) and included other experts and enthusiasts (naturalists, botanists, bird taggers, hunters) in your process in various ways. Can you tell us a little about your research and collaborative processes?

BB: I consult with experts in order to come to a deeper understanding of what I am photographing. There’s so much to learn, even while photographing a small patch of land, like in The Meadow. What insects and animals live here? What food could I forage? What lives were lived here? One photograph leads to so much more.

As part of The Meadow, Margot Anne Kelley and I walked the meadow with firefly, ant, and bird experts, among others. Those conversations opened up entirely new worlds to us.

HJ: What tips do you have for maintaining and developing a photographic practice? How has yours changed over time?

BB: You just have to love it.

When digital photography and printing came onto the scene, I was eager to embrace this new way of working. My book, Behold, published by Datz Press was made mostly with digital capture. Those images would have otherwise been impossible with the 8×10 camera. Now, I have a hybrid analog and digital practice.

HJ: I’ve heard you talk about digital printing opening up new opportunities for photographers, particularly younger or emerging artists. Can you talk about what you perceive as the possibility of these technologies?

BB: Access to in-studio, exhibition quality inkjet printing opens so many doors to young photographers in terms of experimentation, paper choice, and bookmaking. In the beginning, the big thing for me was that it meant my students could continue working after graduation without having access to a darkroom.

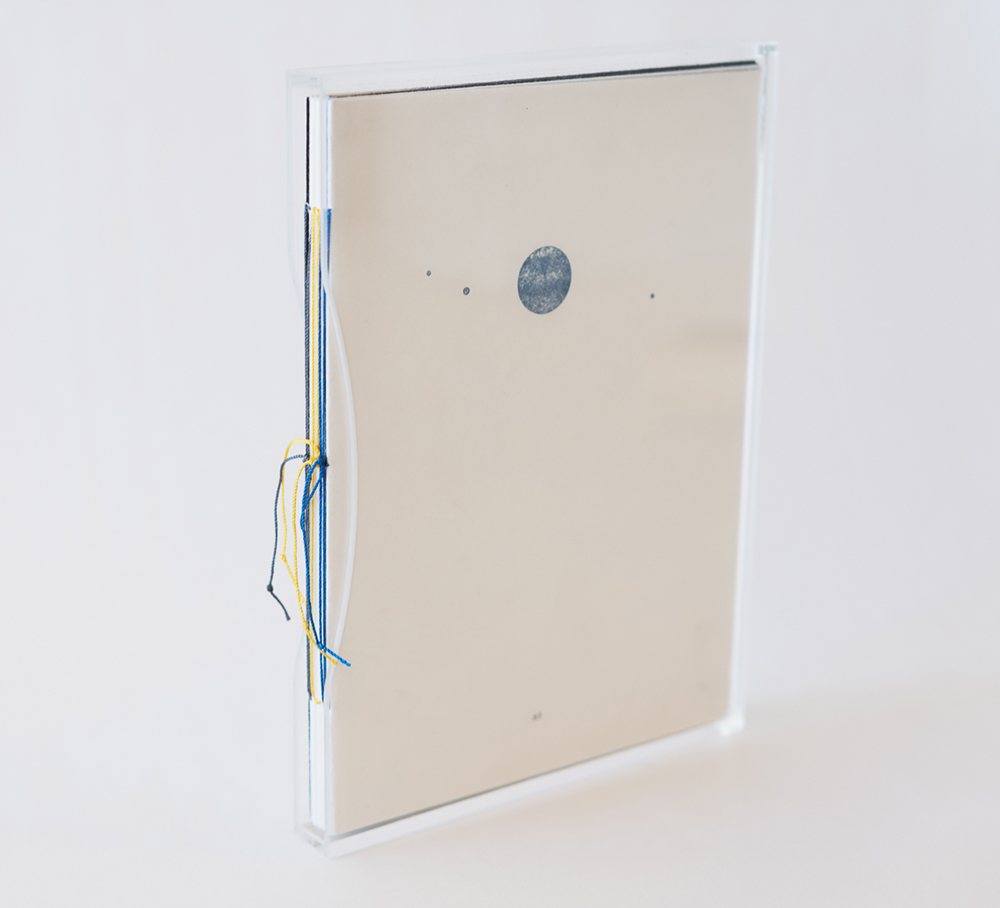

HJ: You’ve made many books, in many forms, especially over the last 5 or 6 years, with publishers such as Radius, Datz, and TIS, but you’ve also done a lot of smaller hand-bound books and zines (many with your studio manager Emily Sheffer at Dust Collective). Can you talk about this explosion of publications? What leads to the format and printing choices you make?

BB: Handmade books give me freedom to work with smaller groups of images. Not every project I make needs to live in a traditional, hardback monograph. Emily Sheffer leads these projects in my studio. We both enjoy experimenting with paper, binding, and design choices. It’s become a main part of my studio practice.

I am drawn to books because they live within an incredible tradition of bookmaking that spans centuries.

HJ: Looking through your book The Heavens the other day, I pulled off the dust jacket to find tape on the spine printed with one of your night sky images. It is one of many unique details in your books; others include facsimiles or letterpress and foil stamp components. How do these extras come to be, and can you tell us a few of your favorites?

BB: I also love those small details. David Chickey is the founder and designer at Radius Books, so credit goes to him for many of the design choices in my books published by Radius.

They are so good.

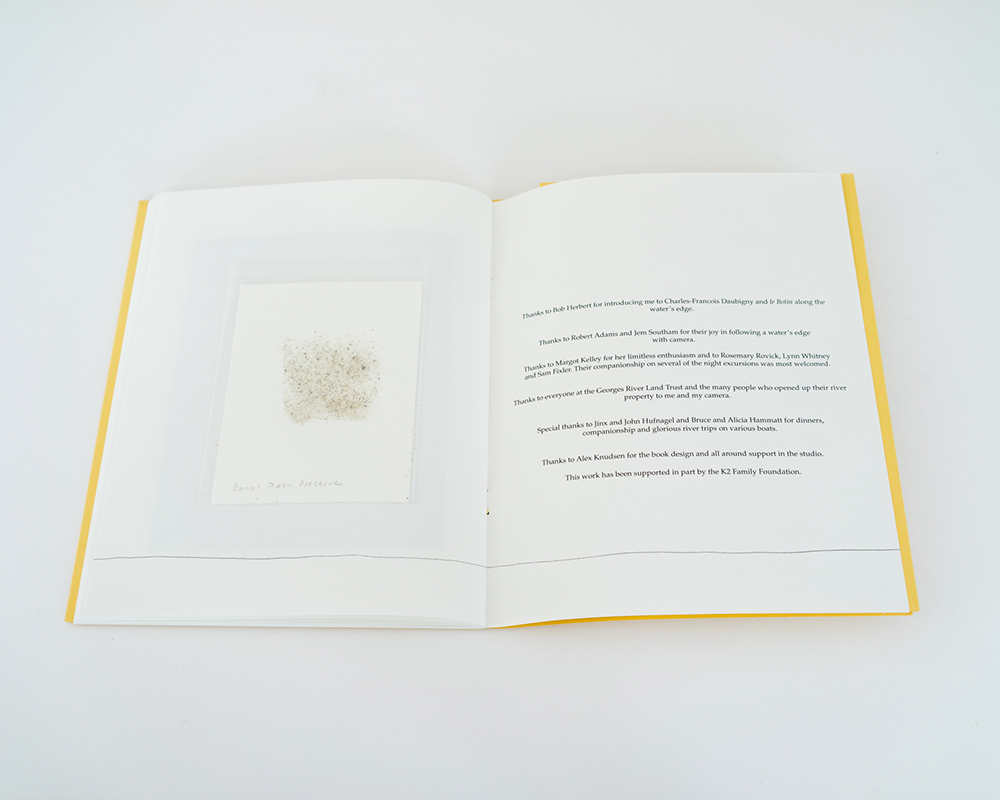

I was introduced to letterpress printing decades ago, so I pay close attention to all of those potential design choices when putting together a book. I love adding little surprises, like in my self-published book Summer Days, which is a look at a river in Maine. I collected sand at every spot I made a photograph. I then glued the sand to a small card included in the back of the book.

HJ: I love that.

As you are developing a project do you envision the final result, are certain images working toward a book while others will be an exhibition? You also have a couple of Instagram projects (@barbarabosworthweather and @birds.intheworld). How do you use these various avenues of sharing images, and how do they differ in your mind?

BB: I often do not envision the final result. I just make pictures. I get excited about something, then I need to make a photograph. That’s where my heart is.

I let things develop naturally, and their appropriate avenues reveal themselves over time.

I wanted my weather reports to be a daily recording of my surroundings attached to photographs of the sky, so Instagram seemed like the natural place.

HJ: Your book One Star and a Dark Voyage begins with a short and beautiful quote by Charles Wright, “The visible carries all the invisible on its back.” Can you talk a bit about what this quote means to you? And about writers that influence you?

BB: Poetry has lived large in both my photographic and teaching life. I was reading Charles Wright’s poetry collection A Short History of the Shadow, while I was making the images that became One Star and A Dark Voyage. That line has stayed with me. To me, it describes what I hope for in my photographs.

On the first day of my Landscape Photography course, I read Waiting by Raymond Carver, which describes moving through and arriving at a place and a loved one. Poetry looks at the world through metaphor, which mirrors the way I think about photographs.

HJ: Yes, thinking of photographs as metaphors resonates with me. I also had an earlier version of this question that mentioned Raymond Carver. I remember you reading him when I was in your undergrad classes.

BB: Yes, it was great having you as a student in my classes! A collection of poems by Raymond Carver, A New Path to the Waterfall, is one I often return to. I like Carver because his description of the visual world is very photographic and immediate. It gets me.

HJ: A professor I had in graduate school works with various mediums, but she considers herself a photographer first because she says she loves the language surrounding it. I guess this leads me to two questions. I wonder if you have some favorite photography-related language or if there is another field you have that feeling about? I don’t know much about geology, but I find myself drawn to some geology terms. Or is there another aspect of the photographic process you particularly treasure?

BB: I agree about geology words. I also love words about the weather. Did you know that swullocking is an old southeast English word meaning “sultry” or “humid”? If the sky looks swullocking, then it looks like there’s a thunderstorm on its way.

I do love the word “photography” itself, with its etymological, Greek meaning, “drawing with light”. How simple and wonderful is that?

For me, the language of photography needs some work. We shoot someone. We blow up a negative. We take photos. In teaching, I try to encourage substitutions. We photograph someone. We enlarge a negative. We make photos. It’s a small but important change.

And, what’s up with punctum? Nobody knows.

HJ: Swullocking, that’s a great word. And “drawing with light” is a wonderful description. I think one phrase she loved was ‘circle of confusion,’ ‘circle of indistinctness,’ or ‘circle of least confusion,’ having to do with the depth of field. I agree; there are also a lot of words to be avoided and replaced around photography. Making a photograph is much preferred to taking one.

I think a lot of what I treasure about photography is related to using film: the way things look on ground glass, how moving water becomes cloudy in a long exposure.

Do you have any new projects on the horizon you’d like to talk about?

BB: I also love how the world looks on ground glass.

I’ve always wanted to do a project with English photographer, and my friend Jem Southam. He’s a fellow 8×10 landscape photographer, though in England, he would say 10×8.

We’re looking at the botanical connections between where I live in New England, and where he lives in England. With Emily Sheffer at Dust Collective, we are making a photo book about apple trees. Apples have a long natural and cultural history in both of our places.

BB: Thank you, Helen!

HJ: Thank you Barbara! It was wonderful to catch up and talk photography with you.

Helen Jones holds a BFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and is currently pursuing an MFA at the University of Texas, Austin, with expected graduation in 2022. In 2010 she started a photography publication, Incandescent, and its imprint, Pine Island Press, with a couple of friends. Lately, she runs them on her own and recently released the twentieth issue. Helen’s work explores interactions between people, places, and landscapes. Her aesthetic is one of things built up unintentionally and of imprints left behind. Her work has been featured online on sites such as F-stop Magazine, Float Magazine, From Here On Out, Lenscratch, and Nowhere Diary; and in print in Subjectively, Objective’s Monthly Monograph Magazine. She has exhibited in group shows at the Visual Art Center (Austin, Texas), UnSmoke Systems Artspace (Braddock, Pennsylvania), Vermont Center for Photography (Brattleboro, Vermont), and was included in the Pacific Northwest Photography Viewing Drawers at Blue Sky Gallery (Portland, Oregon).

Follow Helen Jones on Instagram: @helenjonesphotographs

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

Mara Magyarosi-Laytner: The Untended GardenOctober 8th, 2025

-

Conner Gordon: The OverlookOctober 4th, 2025