Photographers on Photographers: Jordan Mount in Conversation with Craig Stevens

I met Craig Stevens this year when I took his Intro to Inkjet Printing class at Savannah College of Art and Design (known as SCAD). From the first day, he shared countless stories from his career and life. Sharing anecdotes about the photographers he’s been able to work with either as his mentors or alongside at various workshops, printing work for numerous shows, and the extensive list of photographers he’s taught. Being a part of his class and hearing his experiences and viewpoints on photography lead me to a new perspective on photography. He has a true passion for photography’s ability to deeply impact individuals and an extensive view of its possibilities. He’s taught me that you cannot hide from yourself with your work, that there should be intention behind your choices and to trust your instincts. I’ve greatly resonated with the way Craig articulates his ideas on art and life. Which is why I am excited to sit with him at his home in Maine to ask him even more questions regarding his career and photography.

Craig Stevens is a photographer, printmaker and educator. He has taught, written and lectured extensively on the subjects of art, photography and education. Craig is in his 35 th year at the Savannah College of Art and Design where he holds the rank of Professor Emeritus. Prior to SCAD Craig was the Associate Director of the Maine Photographic Workshops from 1975 to 1985.He is periodically on the faculty of the Maine Media Workshops, the Santa Fe Workshops and the Anderson Ranch Art Center in Snowmass, Colorado. Craig served as Director of Workshops for the 25 th Anniversary of Les Rencontres Internationale de la Photographie in Arles, France. Craig was the first recipient of the Susan Carr Educator Prize awarded by the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP). His work is held in numerous public and private collections worldwide.

Follow Craig Stevens on Instagram: @craigstevensstudio

Jordan Mount: I know you started your career as a teacher, how did you make your way to photography and eventually teaching photography?

Craig Stevens: Essentially, I was a second-grade teacher right out of college. I got a job teaching in Dixfield, Maine. I had a guy come to my house “working his way through college” selling magazines. I’m a sucker for anybody trying to earn a living, so I bought a five-year subscription to Popular Photography Magazine. I had been interested in photography my senior year of college. The art museum was across the street from my fraternity house and there was an exhibit by a Maine photographer named Kosti Ruohomaa. That got me started. When spring break came around, I took my income tax refund and went to Boston to buy my first camera.

I decided to go to graduate school because I really loved teaching and I wanted to work on Sesame Street, that was my career goal. So, I went to Fairfield University in Connecticut for communications. They offered an intro to photography class taught by Rupert Williams, who had been the manager of the printing lab at Modern Age Labs in New York. So, I took his class, and we became good friends. He taught me to print, so I learned how to print very well and very quickly. That’s when I decided I wanted to get a master’s in fine art in photography, that’s what I wanted to teach, and Sesame Street went away. I started working on my portfolio and picked 5 graduate schools to send them to.

I ended up going to Ohio University, they offered me a teaching assistant position, covered my tuition, and provided me with a stipend. I applied to Ohio University because there was a guy there named Arnold Gassan who had a book called, Handbook for Contemporary Photography, which was my bible. Arnold taught at the Maine Photo Workshops [now known as Maine Media] in its first year in 1973. I asked him if he needed a TA for the summer, and he said, “Oh God, yes!”. I went with him that summer and was the first TA there. I was happier than I’d ever been. I loved the people, teaching, and being in Maine. At the end of the four weeks, I told David Lyman [founder of the workshops] that I was finishing my degree and I’d love to come back and teach for him. He told me to stay in touch. I finished my second year of school, did my thesis show, and sent letters to every school that had a photo program and received rejection after rejection. But David offered me a job for the summer.

That was the best thing that could have happened to me. After my first summer teaching, David put out an ad for a three-month residency program. It started with me and Richard Procopio as the faculty and twelve students. It ended with up to forty students and four faculty members: Richard, Eugene Richardson, Kate Carter, and me. This kept going until 84. Then I basically became a freelance workshop teacher. I’d teach in a bunch of different places, Bermuda, Japan, Anderson Ranch, and full-time in Maine during the summer.

Once my daughter, Emily, came along I had more responsibilities other than myself and my wife. Then the economy went south, and photography workshops weren’t exactly people’s priority. One day while reading the New York Times I found a little one by three-inch ad in the Career and Education section for a photography instructor for Savannah College of Art and Design. It looked like my kind of experience. I decided to put together a little package and sent it off. Sure, enough I got a call for an interview, even though I didn’t know anybody there they knew me because of the profile I’d established at the workshops. I loved Savannah. I was leaving Maine at the worst time of the year, mud season, and I got to Savannah and there’s azaleas and palm trees and people walking around in shorts. The interview went well, and they liked my work. I told them if they offered me this job, I’d take it. I called my wife and said, “I told them I’d take the job” and she said, “I haven’t even seen the place,” I replied, “trust me you’ll like it”, and she still lives there and works for the college.

I never would have ended up at SCAD if I had not started at the workshops in Maine. There’s so much serendipity that goes into life that you can’t predict.

Jordan: How did you find your way to be surrounded and mentored by so many influential photographers?

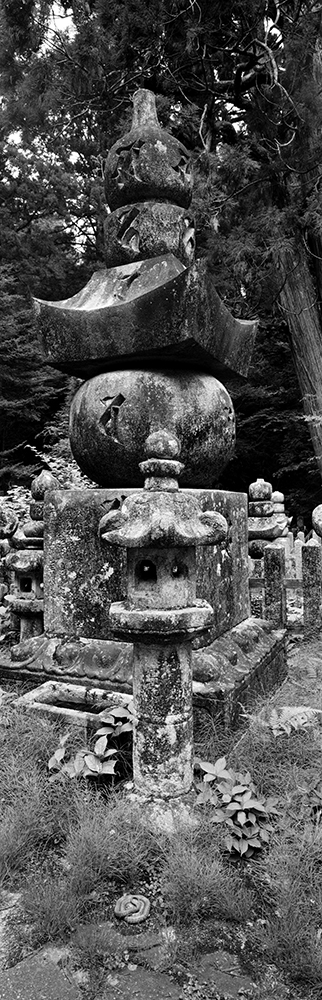

Craig: That had to do with the workshops. About four years into being at the Maine workshops David invited Paul Caponigro to be an artist in residence. Paul shoots five by seven. So, they had to set him up in the dark room with a five-by-seven enlarger. David rented one from Boston and at the end of the summer, they didn’t want to come back and pick it up. They offered it to Paul for less than they rented it to the workshops. Paul was leaving town and he says to me, ” You know that enlarger? I bought it. Go get it and put it in your studio, keep it from getting rusty. When I come back next summer, I’ll use your studio.” So, I ended up with Paul Caponigro in my studio for ten years, a ten-year master class. In addition to that Ernst Hass, who had been with the workshops bought the house across the street from us. I had him to dinner one day and he said, “I’m going to do a workshop in Japan, you should come with me and then you can do it”. So, I ended up going to Japan because of that.

I had nothing to do with this except I was in the right place at the right time. If you go back and look at the catalogs of who was at Maine Media, every photographer of note, almost, that you can think of has been there at one point or another. One of the things that I’ve learned in life is that you want to treat every single person that you meet with the same degree of respect. Just because someone is famous, you don’t treat them any differently. No better or worse. Just because somebody isn’t famous, you don’t treat them any differently. When I first met Cig Harvey she was my TA, Joyce Tennison was teaching at a community college in DC when I met her, Tillman Crane was my student, Brenton Hamilton was my student, and it goes on and on.

It comes down to the fact that I took a chance in Ohio and ended up in Maine. You can’t put a price on that. I have nothing to do with it except I was in the right place at the right time, and I knew it. I mean I could have run away when things got rough. I thought, oh, I could be a lawyer. Thank God I didn’t end up doing that. Something important is having faith in yourself and being willing to take chances and invest in yourself. Often choices that we make are not earth-shatteringly dangerous.

Jordan: How do you keep a balance with your studio practice, making new work, teaching, and your printing jobs?

Craig: I don’t keep a balance. I guess at a particular point I had to decide what was important to me. I think teaching at SCAD, which is a teaching institution, it’s not that people don’t care that you make work, but it’s just not really what you’re evaluated on. You’re evaluated on your teaching skills and ability. So, when I teach, I teach and when I make work, I make work because of the reality of the calendar more time goes into teaching than into making work and I’m okay with that. I guess on my priority list teaching is at the top, and my personal work is number two.

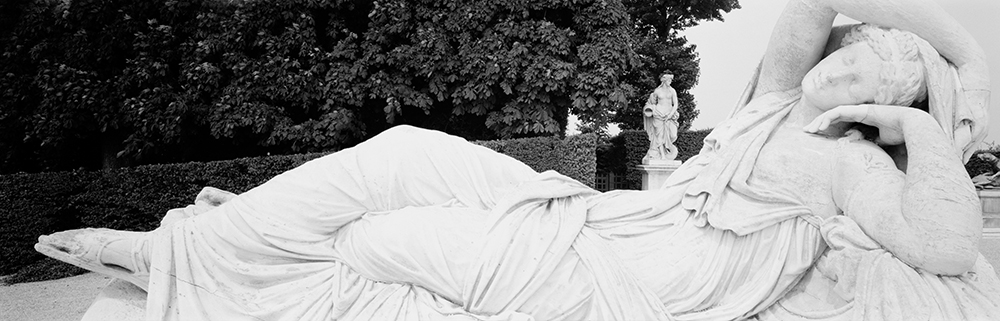

I became a photographer because I fell in love with a print coming up in front of me and I’ve never lost that admiration for the object. I’m an object person. I love paper, I love materials, and I love the way they transform when you start to push them in different ways. For me, that is also important and that comes back around into my teaching because I have no secrets in terms of the materials that I use or what I do with them. I decided at a particular point that if I was going to teach, everything that I know should be available.

Jordan: One of the things you advocate for the most is experimentation. How do you give yourself time to experiment with so much going on?

Craig: Well, you just fit it in. It depends on your personal situation. If you’re single you don’t have anybody else to worry about, you can do whatever you want. If you’re in a partnership, have a family, etc. you have other demands and those are important too because those people rely on you. But even then, you have to be selfish, or you’ll become resentful of those people. So, you have to steal some time for yourself and set up those ground rules. When Emily, my daughter, was growing up I insisted that I had a three-hour block once a week which I would spend in the darkroom.

I used to teach a workshop called Toward a Personal Vision and I would have people who were doctors and lawyers, they would come to Maine for a workshop and that would be their photographic experiences. It would be like if you said, okay, how much food do you eat in a year? Weight it out, so to save time we’re just going to eat all the food at once, then we’ll be okay. Obviously, that doesn’t work. You must nourish yourself. So, in terms of your medium, you figure out a way.

Jordan: I know you mostly as a printer. Of course, in a digital age our interactions with photography have changed so much. Do you think this leaves a chance for greater appreciation for printed work? Or do you think photography is on its way to becoming banal? Can the possibilities of printing be a way to change this?

Craig: Christopher James, one of my best friends, made an interesting comment about digital imaging. That we’re one giant sunspot away from losing everything. Just imagine if all those photos on your phone just went away. More photographs are downloaded today than were made in the first 100 years of photography total. I mean it’s scary because everyone is an image maker now. When I teach history of photography people falsely think Kodak, the first handheld camera, was the democratization of photography. But it was expensive, not everybody would do it. But who doesn’t have an iPhone? That democratized everything. I personally think a lot of this stuff, on our devices, is going to go away and what’s going to be left are the things that we make concrete, which are prints. We can make prints with digital technology now that will last 500 years. Who knows if the world will be around in 500 years the way we’re treating it.

So, will photography become banal? Only if we let it. As long as there are people who want to transform their experience into a physical object that can carry that energy to another person or persons, it’ll stay around. I think it was Tagore that said that painting, music, dance, photography, printmaking, drawing, and sculpture are not art. They’re artifacts. They’re things that are made by art. They are evidence that a spirit reacts with the world and created something and that thing, if it’s successful, carries that energy with it. When I take a piece that I’ve made and I put it somewhere and I’m not there, if another person comes to that piece and experiences something, I’ll never know if they did. But if it does, I did my job. Because if you think about it, the highest purpose that art can have is getting someone to realize their alive. That’s what it’s all about. If you can make someone realize that they’re alive it doesn’t get any better than that. When I stood in front of the Jackson Pollock at the Yale University Museum of art and I was stunned, it wasn’t the painting. It was my response to the painting, that’s the experience. I don’t think that happens on a phone.

Jordan: As someone who has worked with a breadth of photographers, teaching the next generations, and printing well established artists’ work, you’ve been exposed to a multitude of different iterations of photography. Where do you see the future of photography going?

Craig: I think that one of the reasons that the Maine Media Workshops have been so successful and what I tried to carry with me when I went to Savannah was to avoid defining what real photography is. Possibly a lot of schools and places will try to basically say, this is what we think photography is. I would propose a healthier approach to it is to open your arms up like an embrace and say, this is what photography is, a big tent. It has room for the technical, aesthetic, or edgy fine art, and it also has room for the commercial and documentary.

I go back to something Emmet Gowin said to me, in my experience with him he left me with two very meaningful things. I asked him what was the difference between a good photograph and a bad one. He said there’s no difference, some photographs just last longer than others, which I think is a very true thing. The second thing he said is perhaps the most important. That all photographs are documents, but only some of them enter our imaginations. For me, that’s the acid test when I’m working. If it doesn’t enter my imagination, it’s probably not going to enter anybody else’s. So as long as photography can enter imaginations it will have a future. If it doesn’t then it doesn’t, but I have a feeling it will.

Jordan Mount is a recent graduate from Savannah College of Art and Design with a BFA in photography. She is currently working at Maine Media Workshops + College. Focusing on the manipulation and distortion of her subjects Jordan’s work is meditative and expressive, inviting audiences to observe their own experiences and reactions, encouraging a moment of contemplation. She is greatly inspired by the possibilities of the printed image and its objectness as well as how these possibilities of printing can further change how we experience photographic art.

Follow Jordan on Instagram: @jesushatesfunnygirls

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Jessica Hays in Conversation with Dana FritzSeptember 2nd, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Idalia Vasquez in Conversation with Ana Casas BrodaSeptember 1st, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: André Ramos-Woodard in Conversation with Prince Varughese ThomasAugust 31st, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Evan Baden, Aaron Canipe and Sara J. WinstonAugust 30th, 2023

-

Photographers on Photographers: Ian White in Conversation with Curran HatlebergAugust 29th, 2023