Adam Chin: New Visions

Today we feature an in depth interview with innovative photographer, Adam Chin who is creating work in whole new ways of thinking and working. Chin recently opened the exhibition, Machine Learning, at the Chung 24 Gallery in San Francisco running through Nov. 12, 2022 and curated by DeWitt Cheng.

Adam Chin states about his work:

Figuratively speaking, I have spent my entire career trying to make computers walk, talk, and sing.

I have spent nearly forty years trying to make computer generated imagery have the same expressive quality as real photography. And now, by combining photography and Artificial Intelligence, I am exploring how photography can be extended conceptually.

I approach photography from a metaphorical atomic level, i.e., the pixel level, and ask the questions, “What does a pixel know? What does a photograph know?” and by extension, “What is a photograph?”

Adam Chin is a fine art photographer who spent a career as a computer graphics artist for TV and film. He was one of the original employees of Pacific Data Images, a pioneering computer graphics studio which later became part of Dreamworks Animation. Adam did computer graphics lighting on the Shrek, Madagascar, How to Train Your Dragon, and Kung Fu Panda series of animated feature films.

Adam practices using Machine Learning neural networks trained on databases of real photography to render images. By augmenting traditional photography with neural networks, he is exploring the concept of how much information is contained in a given photograph.

Adam studied darkroom photography under Barry Umstead at Rayko Photography in San Francisco. From 1995-2000, he was a board member and chairperson of Intersection for the Arts, a multi-disciplinary arts organization in San Francisco.

In 2020, he was named one of the Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 photo portfolio award winners, and in 2022 he won the 30 Over 50: In Context award from the Center for Fine Art Photography.

Adam has a MS in Computer Science from Stanford and a BS in Computer Science from Yale. He lives in San Francisco.

Follow Adam Chin on Instagram: @adamchin100

Follow Chung 24 Gallery on Instagram: @chung24gallery

Judy Walgren: Adam, thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me today. Let’s start with a description of your background and how you came to photography?

Adam Chin: My background is in computer graphics. I think we’re about the same age?

Judy Walgren: I’m 59.

Adam Chin: I’m 61 and in the early 80s, I got out of school in computer science and wanted to make pictures on the computer. You don’t know yourself then, but I did know I had a visual instinct. And at the time—this was before the MacIntosh—there were only about four places in the country where you could make pictures on the computer, because no one had the equipment and the software hadn’t been written. So, I found one of these places, and it was five guys in a start up in a warehouse in Sunnyvale (CA) and so I joined. There were six of us and we were making graphics for television—the openings for Nightline, the Wide World of Sports and Monday Night Football. We were flying the NBC Peacock and we created the opening for Entertainment Tonight, which stayed on the air for 10 years. That’s where we started. You had to be able to program in order to make these pictures. Prior to that, this was all done on film with optical printers and it was a very complex process. The computer came in and took over this field. I stayed with that company off and on for about 30 years. As the computers got faster, we made commercials and then later we made films. The company was called Pacific Data Images, PDI, and we got acquired by Dreamworks. We competed against Pixar, basically, our entire careers. So that’s where my background is.

Judy Walgren: Very interesting.

Adam Chin: Over time, the company became big and corporate, so I finally left—I think I got bored. But back in those early days, the reason we went to that company, when there were six of us, was that we could sit there at night after you finished your work, and the computer was yours. You could make pictures. We would sit there and try to make the coolest picture we could think of on the computer. And if I look at what I’m doing now, I’m doing that again, but now I’m doing it at home. My mentor is one of those original six guys and I talk to him every other week about AI and he’ll say, “Go look at this paper or go look at that,” and I’ll show him what I’m doing. Having this mentor really helps me. So basically, now I sit at home trying to make—I mean I am over simplifying it—to make the coolest picture that I can think of.

Judy Walgren: Who is your mentor?

Adam Chin: Richard Chuang and I’ve known him for 40 years. He’s like a Big Brother to me, he was the true computer genius at the company. I’m very lucky to have that.

And then the photography part: I started taking darkroom classes in school, but eventually the cameras got put under the bed, and I didn’t use them for 15 years because we were working so intensely—like a lot of people do.

I had an uncle whose name was Benjamen Chinn and he was a photographer. We (the family) helped take care of him before he passed. He was a student at the San Francisco Art institute or the California School of Fine Arts, and he was part of this cohort that Ansel Adams, Minor White and Imogen Cunningham were teaching.

As he was getting older and the 2000s—Benny was very humble and quiet and never talked about how he was buddies with Imogen Cunningham and friends with Edward Weston—he started opening up and we found out that he had this rich history and legacy. He was up to 80 and he would walk from his home in Chinatown every year to the Pride Parade in San Francisco and take pictures there, like Minor White had taught him to. I started taking care of his archive with two cousins and it rekindled my interest in photography.

Judy Walgren: That’s an amazing story!

Adam Chin: Yeah, he was a cool guy. We have found a letter to him from Imogen Cunningham asking him to buy the house next door to her so they could be neighbors. They were that close.

Judy Walgren: This archive—where is it now?

Adam Chin: We donated it to the Center for Creative Photography in Arizona and that’s actually where Benny wanted his stuff to go. And then we gave a whole bunch to the SFMOMA and then we’ve got a couple more left that we are dispersing around the Bay Area.

So that rekindled my interest in photography, and I picked up my cameras and started going out to the Pride parade and trying to see what Benny was seeing. I was studying what Minor White taught him, what Alfred Stieglitz had taught Minor—that’s what I was able to trace back.

And then the final thing that came together was that in the mid 2010’s—2015 and so forth—I had stopped working because I was, I think, burned out. Commercial production is pretty intense. I was taking care of my mother and she was in assisted living in San Francisco. And actually, we were having a good old time—I was more than happy to do that. But I always knew that when she was gone, I was gonna have to go back to work. You know that in the tech industry, I’m too old. I’ve aged out by two generations and I know that. I know the mentality. And so I was sitting there thinking that maybe I don’t want to go back to what I was doing. Maybe I should learn this AI stuff? This was around 2015.

Judy Walgren: So smart.

Adam Chin: There was this tech boy arrogance there that said I could learn it. But I also know that I have limits. I ended up going to Coursera and taking a couple of machine learning classes and they were hard, I mean I had to pull up some math I hadn’t used in 30 years. They were good courses. And so the question is – can you retrain yourself as an older person—it’s not a given that you can do it.

Judy Walgren: Right. I am right there with you.

Adam Chin: I saw my limits—Google’s not going to give me a job. I know where I topped out. But I was able to learn enough to make pictures and the only way that I was going to be able to learn this was if I could make pictures with it. This was in 2015 and it all comes around to what I was doing 40 years ago. It didn’t take long, though, for me to realize that I was really early [in this technology]. You could barely make a picture, maybe one the size of a postage stamp and it was really blurry. I realized again that I ended up on the front edge of this thing.

Judy Walgren: And now there’s Synthetic Media and Deep Fakes…

Adam Chin: Exactly so this is all happening. So now it’s just a matter of trying to keep up to date. There’s this wave of work that’s just going to crash over all of us and surpass what I’m doing and I and I’m happy with that.

Judy Walgren: Did you get another job?

Adam Chin: That’s a good part of the story. I never went back to work. I was able to kind of like skimp by—my mother did pass away a couple years ago – and if I don’t spend a lot of money, I’m okay. I finally realized that I’m more engaged making up my own projects than working for someone else. I’m happier.

Judy Walgren: Good for you.

Adam Chin: I’m lucky.

Judy Walgren: Where’d you grow up?

Adam Chin: I grew up in San Francisco, in the Anzavista neighborhood, actually. I am still very nostalgic about San Francisco. It was extremely multicultural growing up in the 70s. The high school was one third Asian, one third African American and one third white—in all the schools. That was San Francisco back then—it’s not the same now.

Judy Walgren: The change in demographics was a very hard thing for me to watch. It was extremely difficult to see what was happening right in front of us. I was at the San Francisco Chronicle and we did a number of stories on it and a documentary, actually. And you have been there your whole life so you’ve seen this happen over and over again, over time.

Adam Chin: I’m trying not to become a grumpy old man, but…

Judy Walgren: I keep thinking about Michael Jang and his work and the legacy of Chinese American photographers, American photographers, and how important it is to protect and to celebrate not only Michael’s and Benny’s legacies and archives, but yours as well. These narratives need to be celebrated.

Adam Chin: Yes and you know even Benny never talked about his artistic side with the family. We had to almost pry it out of him. I remember one day in the 1990s, I was shooting a little film. I was learning how to make 16 millimeter films and I said, “Hey Uncle Benny, why don’t you come by and help me light this cafe?” And we were having lunch there during a break, and I said to him, “Hey you know Berenice Abbott just died—it was the newspaper.” And he said, “Oh yeah, I used to go shooting with her.” It was a Chinese thing I think. His family had about 11 brothers and sisters and being an artist was not truly encouraged. Almost all of them became engineers.

And when I went to that computer company in the early 80s, the thing that ran in common with the six of us was that we were engineers, but we were all frustrated artists. We were there because we wanted to make pictures, but we ended up in engineering for some reason. I think it’s cultural. I don’t know how it is in Asia, but the Asian American immigrant experience—you really weren’t encouraged to be an artist.

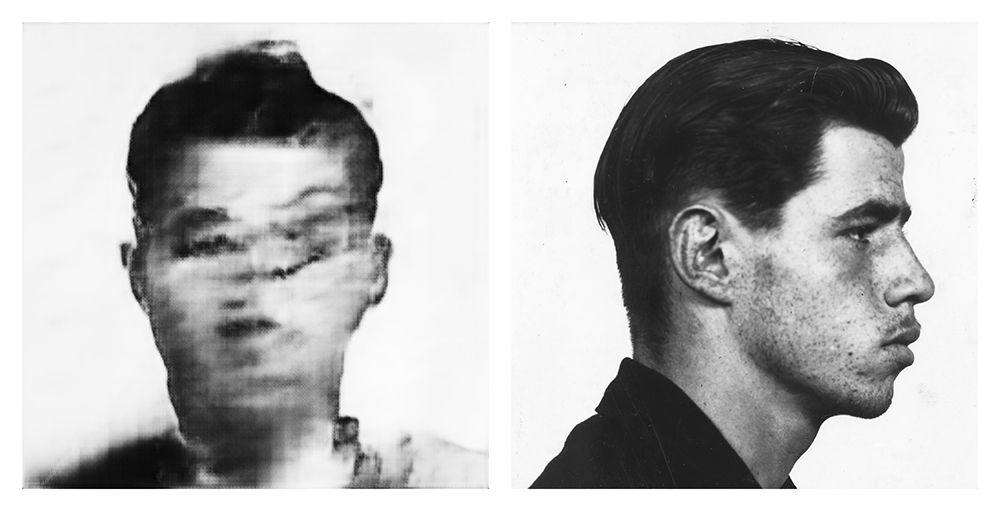

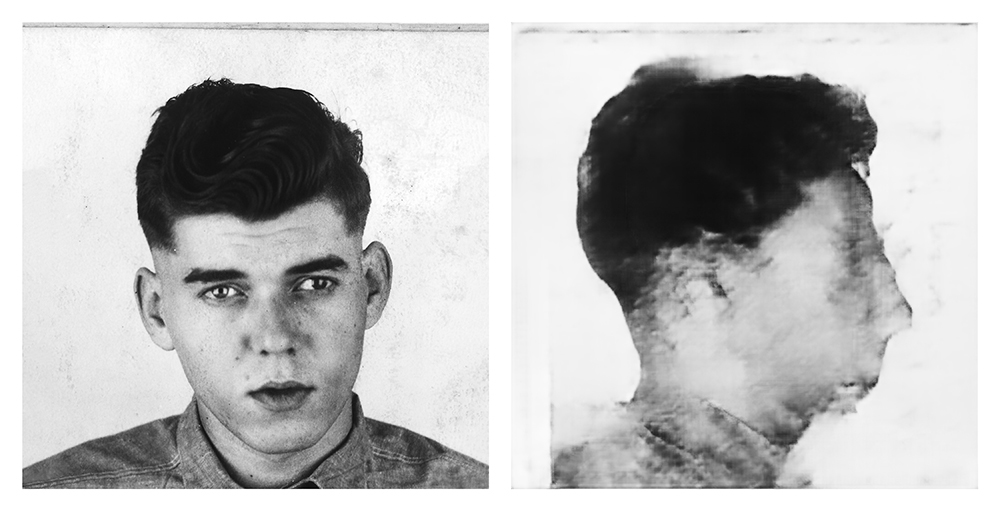

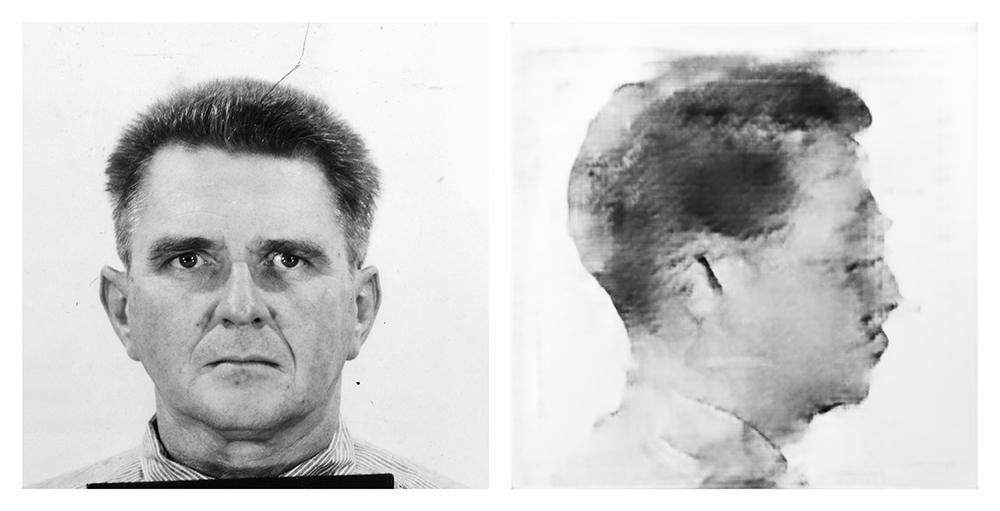

Judy Walgren: So, you found AI and your way in photography again, as well as a way to make photographs using software and algorithms. Could you talk about your bodies of work and how they track your artistic trajectory? Maybe starting with your project titled “Front and Profile?”

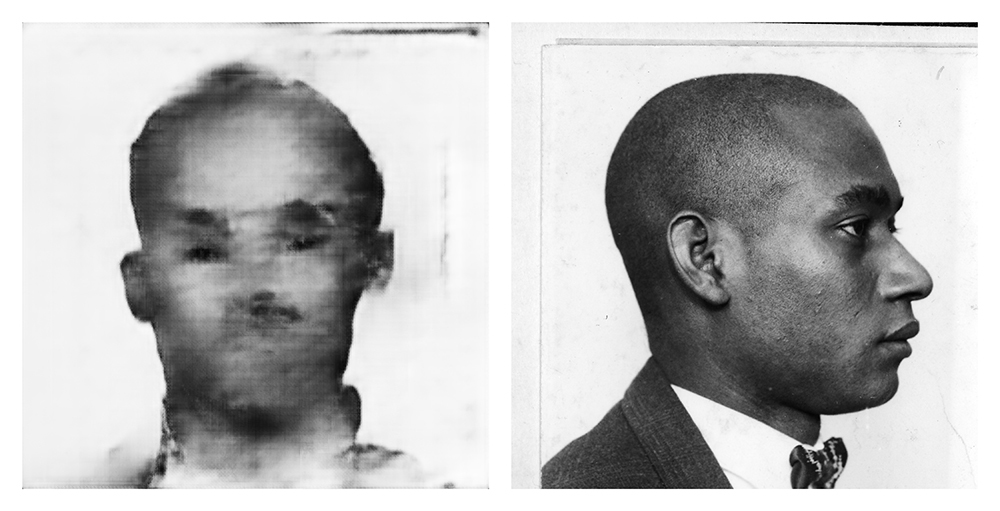

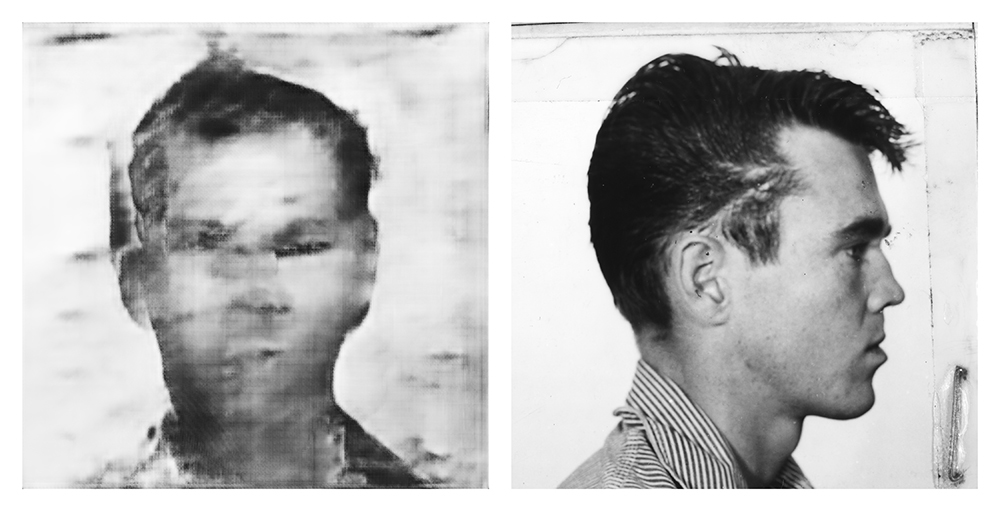

Adam Chin: Yeah—the mugshots and then this is where it gets really interesting, you know, because the actual impulse there was that I wanted to draw some faces. What could be more benign than that? I mean it’s a very natural thing – like cave paintings. Can I make this thing actually draw? But what I uncovered was a lot of the issues that this whole AI thing is going to have as it moves into making pictures. If you want to draw faces, then you’re going to need a database of faces—a pile of faces to work with.

And that’s where you start running into issues. The first thing I found was a free database from the Federal Government of these old mugshots. There are no names, there are no crimes attached to it and it was made for AI researchers to benchmark their algorithms—to test them. So, I downloaded it—this is like 2016—and I opened it up and the first thing I saw was that half the men in there were African American.

The images ranged from somewhere between the 1930s and the 1970s or 1980s and I was shocked. I was like, “This is really uncool. I can’t use this. There’s something really wrong here. So, I just put it away. How could I go to present work and give a talk about it, knowing that what I had received was a racially biased database? I actually walked away from it for a year and looked around for other faces and couldn’t find anything. I still wanted to draw pictures of faces, and so I went back to it, and I said, “Well, maybe that’s the point. If I use this, then I’ve got to talk about these issues, and what I found.”

And here are the issues I found. One – there is the issue of privacy. If you’ve got a pile of faces, do you have the rights to use those faces? And if I’m drawing a new camera angle, you know from one picture, do you have any privacy rights, as an individual, in there? And also, is it accurate? This became the big issue with police facial recognition—faulty recognition— and all the false arrests that had happened up to last year. They were usually African Americans that were falsely arrested because there’s a photographic bias. Kodak was set up for white skin over the years, and so photography in which people have darker skin like in mugshots and in class photos was always quite poor historically. Exposures for film were set for white skin.

So what I found is that there are going to be a lot of problems, a lot of issues, as we move forward with AI making pictures, things you hadn’t thought about and they’re here now.

And when we start talking about “a Man Eating Sushi,” that has more legal issues than technological.

Judy Walgren: So then, the goal for the “Front and Profile” project was to…?

Adam Chin: To predict the other camera angle. Machine Learning is a prediction; it’s a probability engine. When we were growing up, computers said either yes or no, true or false, zero or one. It was binary. Now what the answer a machine learning neural net gives is, “Given what I have seen before, this is the most probable answer.” It’s a complete gray area, and it’s not zero or one anymore. So, “given what I have seen before”? Well, what have you seen before? You’ve seen this biased data set. As this whole AI comes into our society, we are going off into uncharted land here and a very troubling one where there are no longer any absolutes. The machines aren’t giving us absolutes anymore. Everything is a most likely prediction. That’s the answer that a machine learning neural net gives so that’s the picture that we’re getting in “Front and Profile”—a prediction of what the other camera angle would be.

Judy Walgren: So, you took the profile and then using AI, you tried to predict what the front angle would look like given this biased data set of mug shots.

Adam Chin: Exactly.

Judy Walgren: Where is this database from?

Adam Chin: It was from the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Every database is biased. Anytime you make a selection out of the whole there is bias. Can you make a socially correct database? A correctly balanced database that produces images based on the exact ratios and percentages of what our country is made up of? That’s a much harder problem. As a tech person, I can easily say, “Hey, I’ve pulled together 5 million images and made this cool database. That’s easy. The hard problem is, “Can you make a socially balanced database?” That’s a much harder problem.

Judy Walgren: This is such great information. What years did you work on “Front and Profile” then?

Adam Chin: 2019.

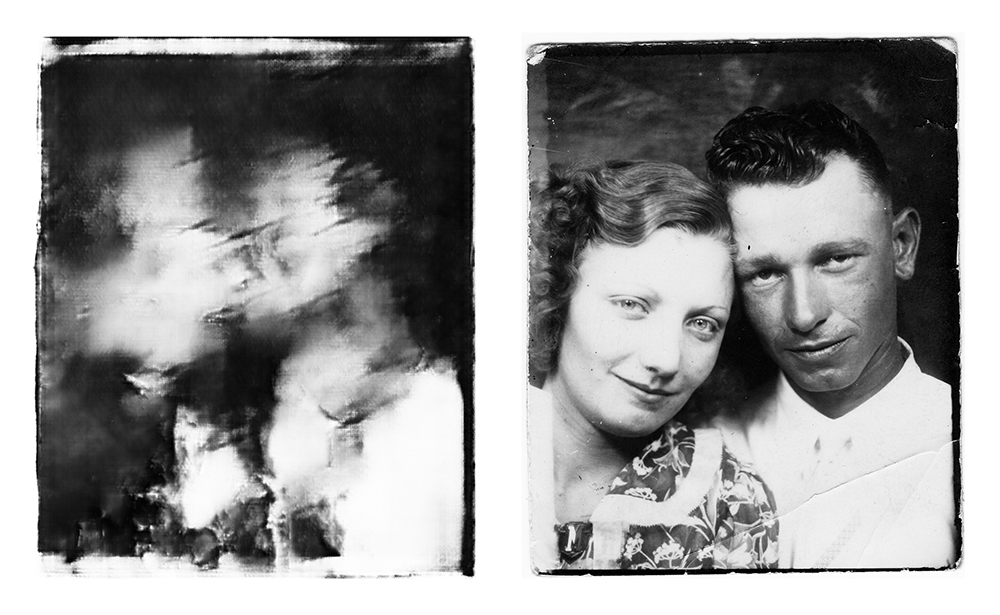

Judy Walgren: Ok, then that led to the “Photobooth Kiss” project?

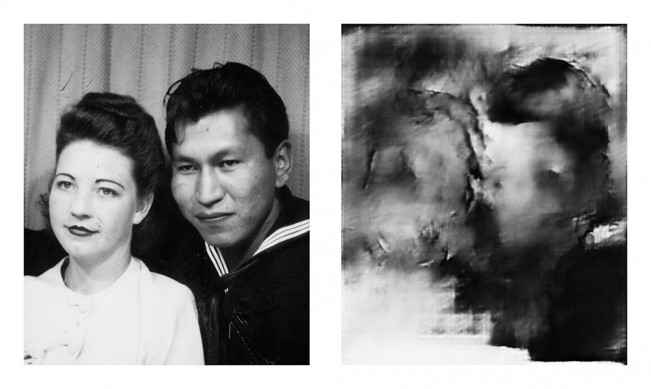

Adam Chin: Yes, definitely. I spent all of last year, 2021, working on the Photobooth Kiss project, even though the algorithms were from 2017. The algorithm is aging out now, but I decided to stay with it anyway.

And here’s the cool part about “Photobooth Kiss”—with a database of mugshots, I have two photographs of each person. I started to think about what other situations were there of people that yielded more than one photograph? Photobooths—you have four pictures! So I started collecting photobooth pictures and was just looking at what I had, thinking that I must be able to do something with them but I’m not sure what. And after staring at a whole bunch of them for a while, what I found was that usually in the third or fourth picture, people start kissing in the photobooth.

And after a while, I decided that I wanted to predict the kissing photos, which was a really out there idea. So I started to cobble together this tiny database, it was like 200 photos which is really not enough for anything. So, I would take two photos from each strip, one kissing and one non-kissing and show it to the machine learning algorithm. . I did that over and over 200 times so that the AI could predict what the two people kissing would look like. Then, you bring in a new photo, one that the program hasn’t seen before. And, given what it’s seen before, what is it most likely going to look like when these two kiss? That’s what it’s trying to do.

Judy Walgren: WOW.

Adam Chin: I mean, there were some days where I felt like I was looking into a crystal ball, or like I was an oracle like in Snow White or Sleeping Beauty. In science fiction, they always have an alt universe… I feel like I’m trying to look into this universe—and it’s very blurry— but in this universe, they’re kissing. With the mugshots, I was changing the camera angle, but here I am changing the actual event—what was happening in the actual photo, because we don’t know if they kissed or not. It was kind of mind blowing to me.

And this is where we get to the “a Man Eating Sushi” project because very soon, this is going to look real— just like just another photograph. And at that point, you’ll be making photographs of events that didn’t happen. It’s going to be a real problem.

Judy Walgren: Okay, so “Photobooth Kiss” then led to the project “A Man Eating Sushi?”

Adam Chin: So, while I was making “Photobooth Kiss,” these text to image algorithms started coming out, but since “Photobooth Kiss” was taking a long time, I wasn’t able to check them out until almost a year later. The first one that came out was called DALL·E and made by a company in San Francisco, it’s an AI think tank, called OpenAI. Earlier there was another little revolution that happened in AI called the Transformer. The leading edge of AI was text and they were starting to be able to process words very, very well. But picture making was lagging behind, because it was a harder problem and it used more memory.

So what they finally decided to do is to hook up their advances in text translation to picture making and they came out with DALL·E. You type in a sentence and a picture comes out. This version of DALL·E was trained on a couple of million images and their associated captions taken from the internet. And this thing starts generating images. They called it DALL·E because there was a surreal element to the image produced. It’s a sort of mish mash. It seems like these systems tend to hallucinate. They’re weird but they find associations and it’s starting to work. Here’s the point—it’s so damn dangerous. I’m actually seeing legal caveats in the tech papers, for the first time in my life, which is like, “Whoa.”

So the moment this thing goes out into the wild, someone’s going to create this image—some awful image —attribute it to this program and at that point, the entire technology is sunk because it will create a backlash. So that’s really the big problem with this technology. Google introduced their version of this technology, Microsoft has their version. DALL·E 2 came out now. They are trying to de-fang these technologies before it’s released beyond Beta versioning.

For “a Man Eating Sushi” the coding was beyond my ability, but I found an open source version. and the guy had actually put people in it. So I raced ahead and I just chose the sentence, “a man eating sushi.” I drilled straight down and made about 1000 pictures and I picked these 10.

The interesting thing is to ask, “Why did you choose the phrase, ‘a man eating sushi?’” And I don’t know—I guess I thought it was a good sentence. There’s no one picture of sushi or someone eating sushi. Is it a roll? Is it a piece of nigiri?

So you look at the results, and I see a lot of the men were sort of Asian or Eurasian looking.

Judy Walgren: Their eyes are all mixed up.

Adam Chin: I think it draws in one eye, then it loses track when it gets to the other eye. And it doesn’t know how to count, so lots of times the hands would come up with 30 fingers. And there was only one really good picture sushi in there and then some very, very surreal associations were made.

Judy Walgren: How long does it take to make one of these photos?

Adam Chin: It’s fast. There are two steps. The first step is training the neural network and that can take hours or days, but once it’s trained it’s just an input-output process. It was more of a curatorial process, as well as a poetic process of coming up with your best text.

What you don’t see with “a Man Eating Sushi” is really the question, “What is this all about?”

The program is trying to create this reality out of content from the internet. It’s like we’re looking through a peephole into the internet and what you are seeing here is a kaleidoscopic view of the contents.

I tried to ask it to show me a picture of a black and white photo of Half Dome by Ansel Adams and it sort of gets it and sort of not.

Judy Walgren: So given this body of work, what’s next for you?

Adam Chin: I’m backing away from these actual text to images, because I know that there’s going to be a whole lot of people doing this. People are jumping all over it. For me, I’m going to continue using just the rendering engine. I’m going to be using the aspect of the program which has made the images look more photographic, which is more satisfying for me. So, where now you see that “Photobooth Kiss” is rough and sketchy, where I’m going next is to make images that will look much more like photographs.

Judy Walgren: Larger files, finer resolution?

Adam Chin: Exactly. Will it be better “Art?” (Adam shrugs). What I realized I liked about “Photobooth Kiss” is that you can actually see the computer struggle.

Judy Walgren: I love that. It’s like abstract painting the way that I am looking at it.

Adam Chin: I felt, which was something I had never felt before, was that I was actually sketching with the computer—which was unheard of. And that was really cool.

You know, if the Photobooth kiss had come back with a perfect picture, would it have been interesting? At this point, I would say that it would have ended the conversation.

Judy Walgren: Beautifully put and I think that’s a perfect place to end. Thank you so much for your time and your thoughtful explanations about what is clearly a complex process. I can’t wait to see what you come up with next.

Adam’s Note: On August 22, 2022, just after this interview, Stability.ai released Stable Diffusion, a robust and publicly available text-to-image program which completely upended the AI art world. The program has created a viral flood of new imagery and also new tools for content creation.

MSU J-School Associate Director and Professor of Practice Judy Walgren is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, photo editor, executive producer, curator and visual artist. She has worked on staffs at the Dallas Morning News, the Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post as a photojournalist and photo editor. She also served as the Director of Photography for the and at the San Francisco Chronicle, where she led a team of Emmy-winning photojournalists and filmmakers. In 2016, she received an MFA in Visual Art from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and began her exploration into the relationships between photography, historic archives and power structures. She joined the faculty at Michigan State in 2018.

Follow Judy Walgren on Instagram: @JudyWalgren

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026