Diane Durant: Stories, 1986-88

For the next few days, we will be looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-submissions. Today, Diane Durant and I discuss Stories, 1986-88.

Diane Durant is Associate Professor of Instruction and Director of the Comer Collection of Photography at the University of Texas at Dallas where she holds a PhD in Aesthetic Studies. She serves on the university’s Committee for the Support of Diversity and Equity and as faculty advisor for PRIDE @ UTD, an LGBTQ+ student organization. Diane is a member of both the Board of Directors for the Dallas Wings Community Foundation and Texas Photographic Society. In 2018, Diane was named one of four inaugural Carter Community Artists with the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and belongs to the permanent collection of the National Park Service. Diane’s first monograph, “Stories, 1986–88,” was released by Daylight Books in 2020. More often than not, she eats cake for breakfast.

Follow Diane Durant on Instagram: @betweenhereandcool

Stories, 1986-88

The difficult business of being human

Growing up isn’t easy. We spend our whole childhood wishing it away, wishing we were older, wishing we could do the things our big brothers got to do, that we could ride our bikes to school even though we’d moved and would have to cross two highways now, there and back.

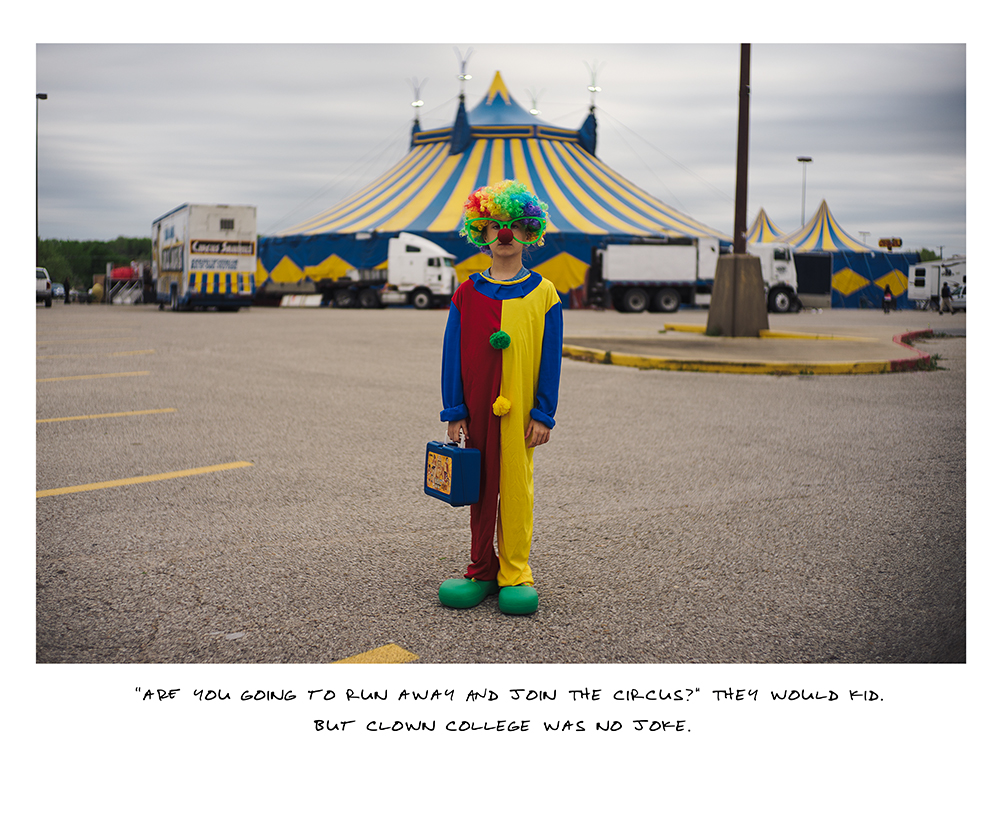

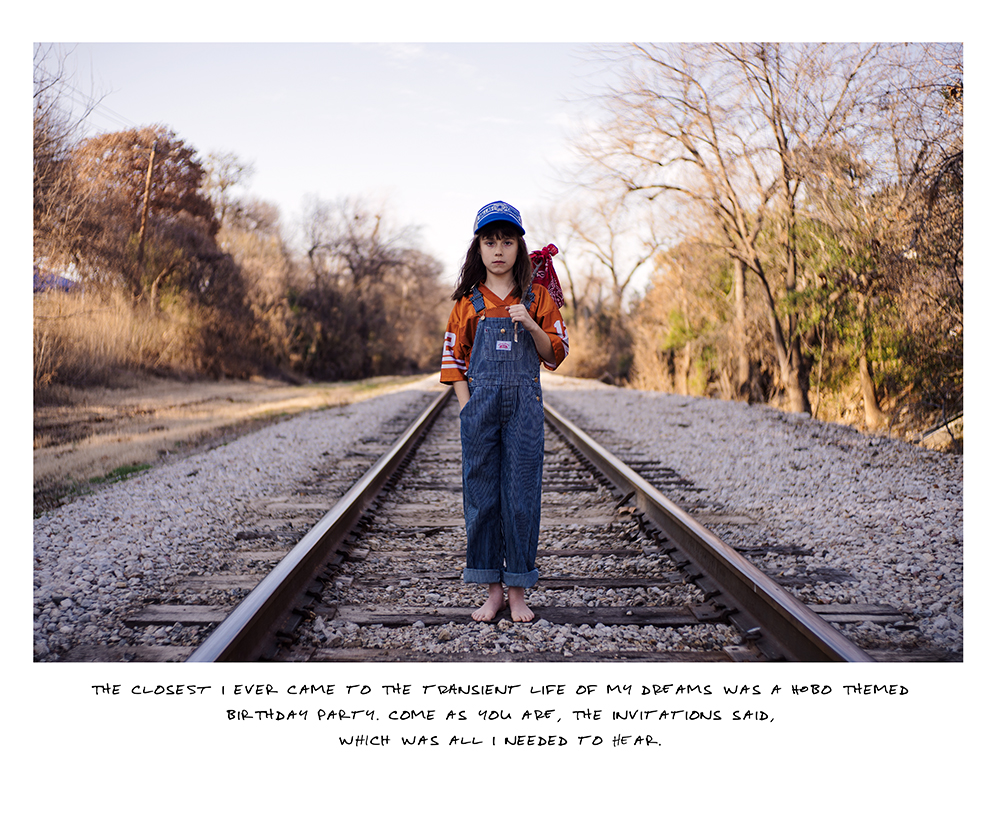

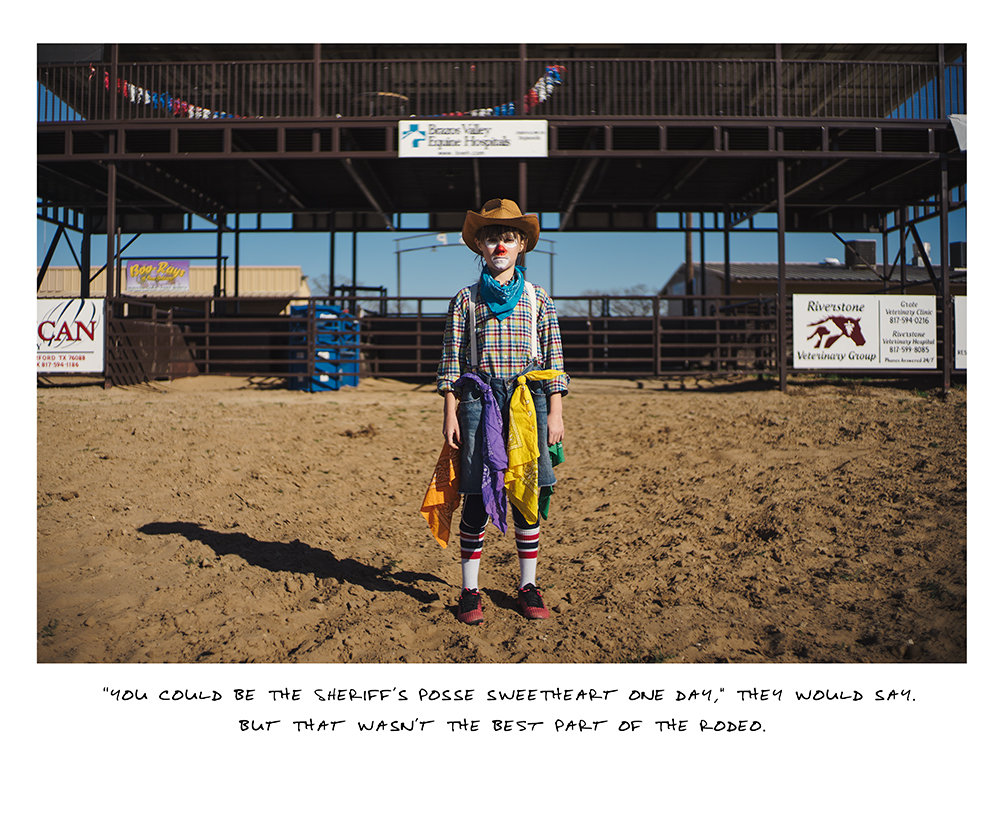

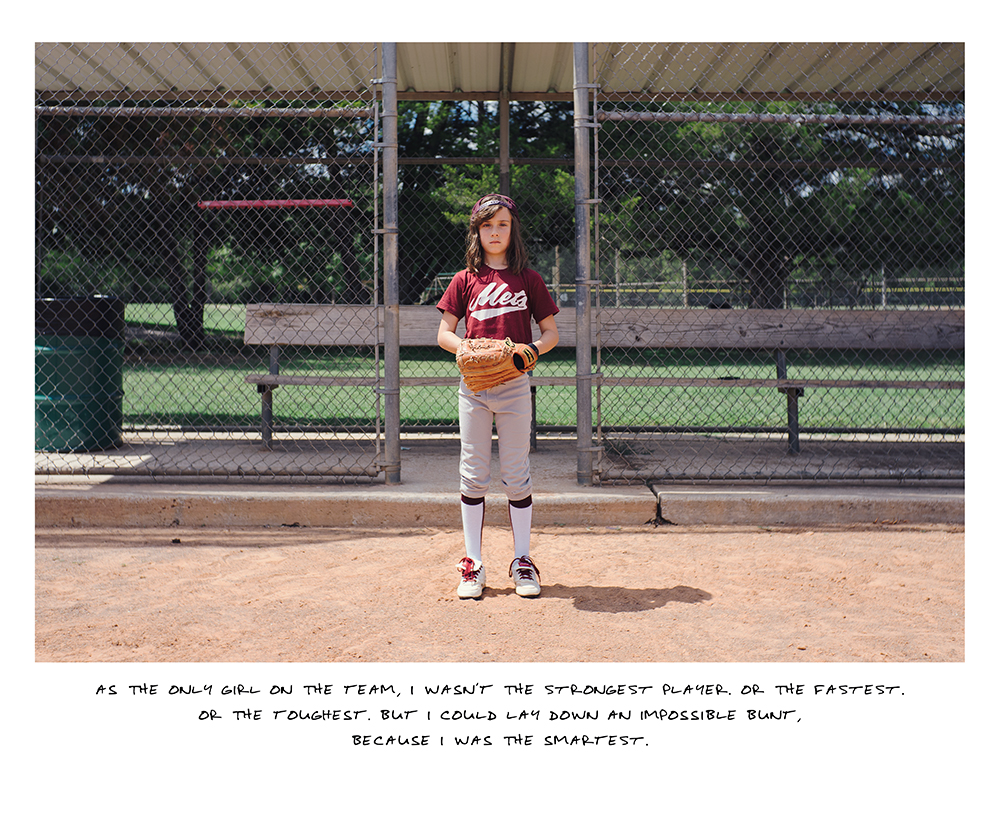

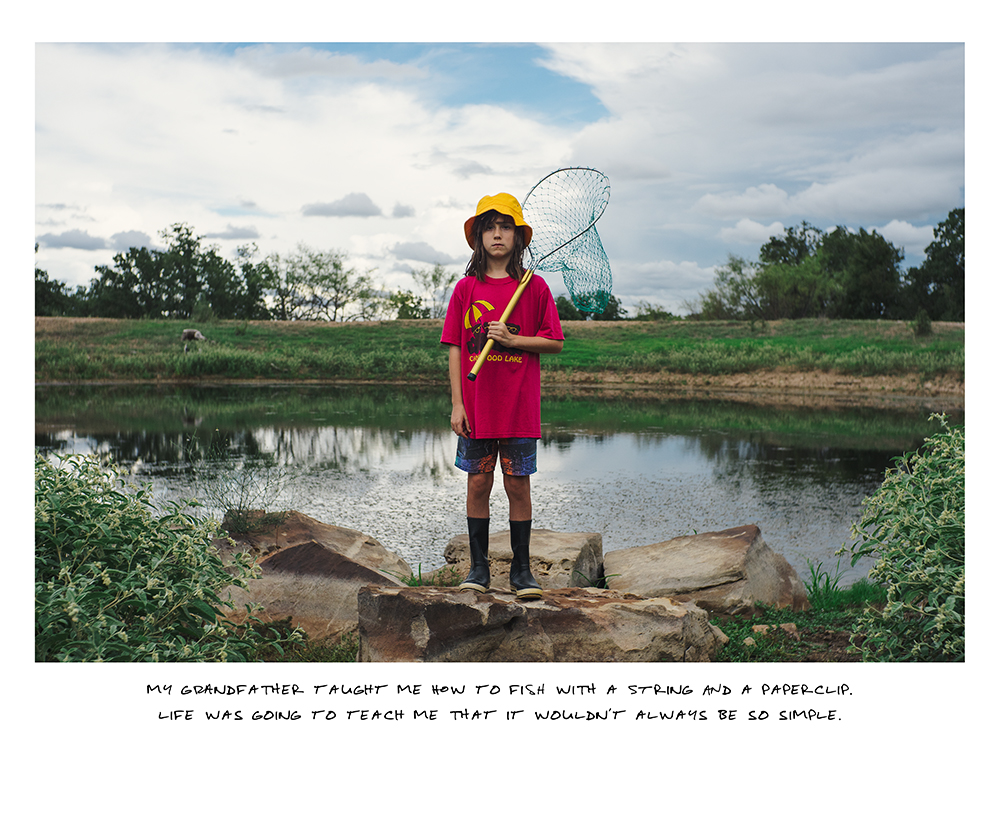

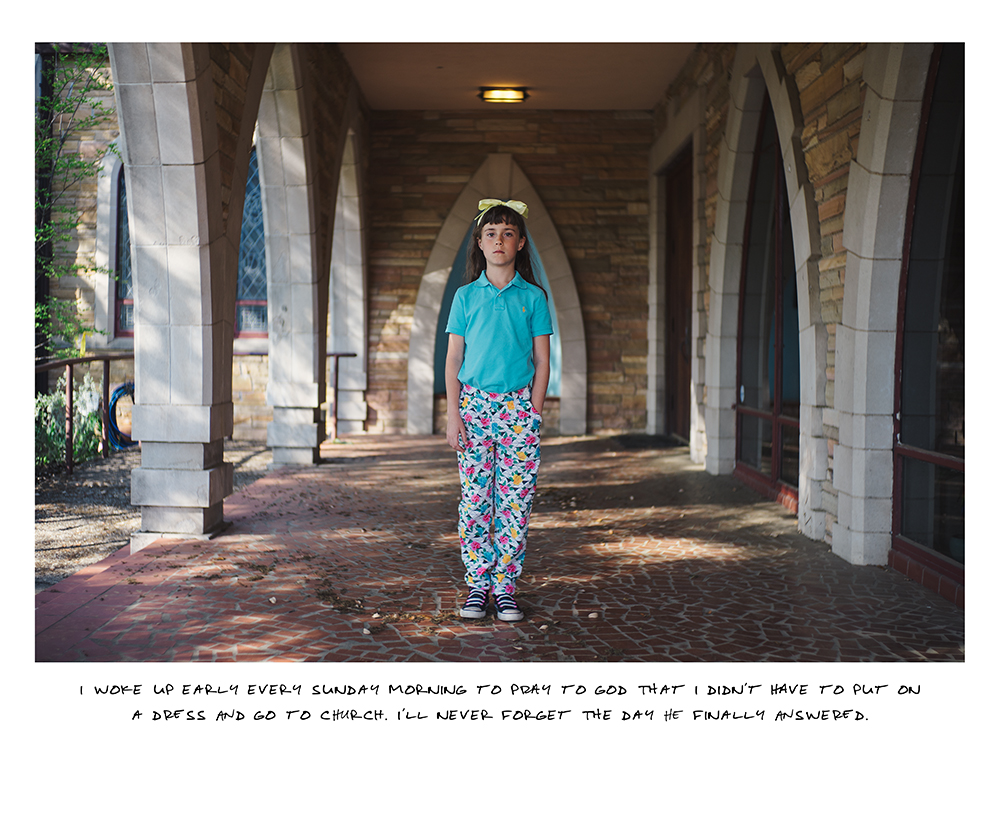

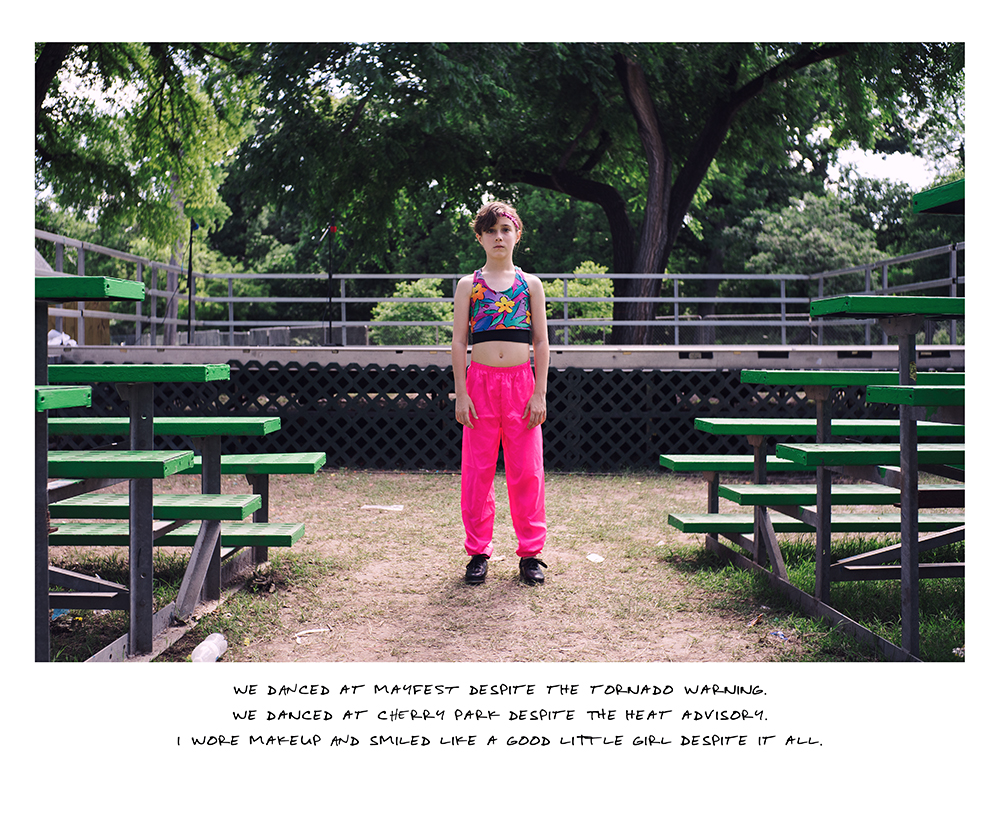

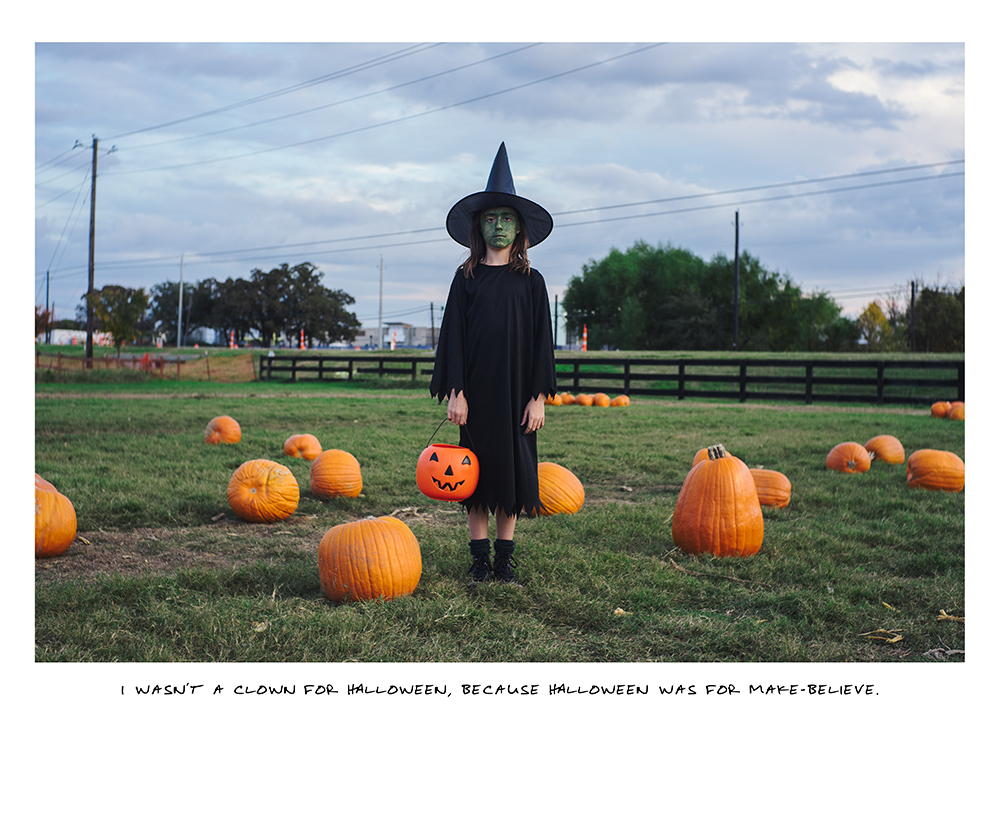

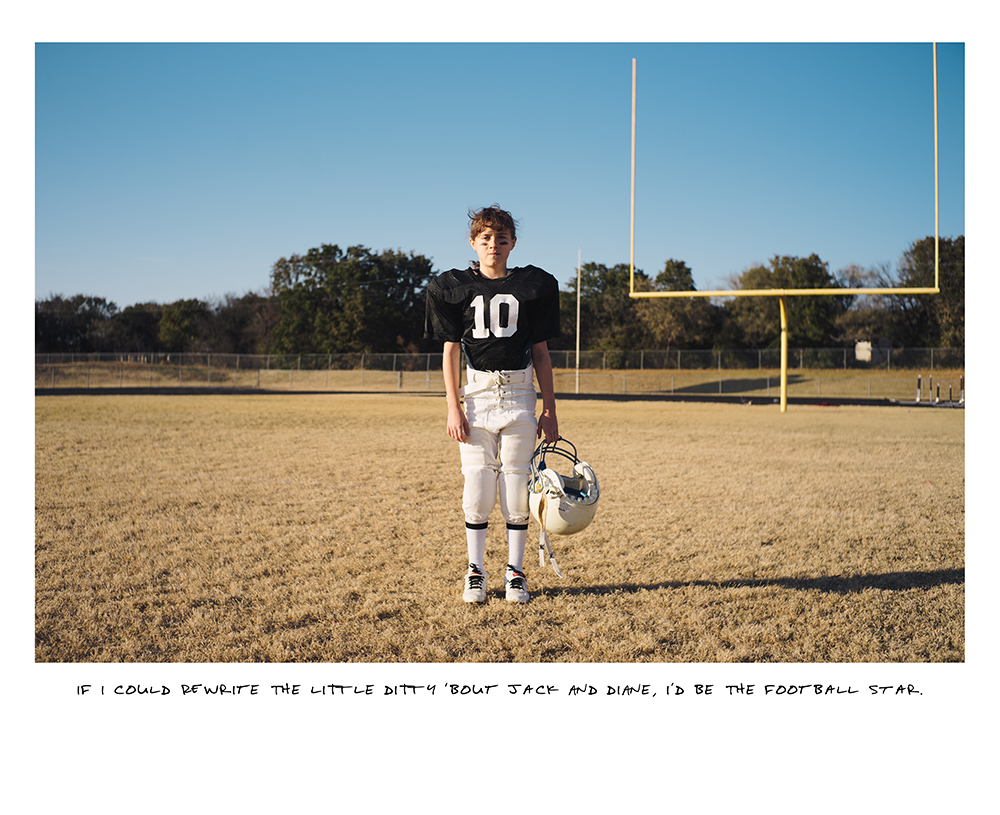

But our childhoods are only the beginning—obviously of our lives, but also of all the disappointment the world will divvy up and how we’ll learn to deal with it, from something as innocuous as not getting to play the trumpet to the more painfully philosophical questions like, Who am I? How’d I get here? Why is everyone yelling? I hid in the holly bushes (both literal and metaphorical) from 1986 to 88, squeezing my eyes tight so I couldn’t see or hear or feel the chaos that may or may not have been as traumatic as I remember. But there are moments, flashes of reality burned into my psyche, woven into the person that I am and that I am continuously becoming—or maybe even unbecoming—and these moments have shaped both my fictions and my truths. Stories, 1986–88 is a little bit of both, a photographic reconciliation of all the things I couldn’t change with all the things that never were, with a dash of adult-level cynicism and a handful of childlike innocence—a synergy as compelling as it is relatable, if not entertaining, hopefully.

Years ago in graduate school I remember reading an interview with French writer and conceptual artist Sophie Calle where she confessed that in each of her works, her creative explorations, there was always a lie. Something she thought she would find but didn’t. As an artist, an aspect of her process included giving herself something that didn’t exist (though perhaps it should have) and giving that something the same amount of narrative weight as the rest of the elements in her stories. Perhaps not coincidentally, her artist’s book, True Stories, relies on a similar pretense—and a consensual relationship between reader and narrator—as this book you’re holding now. These are true stories, even if, to a degree, the contrarieties and juxtapositions are truths that I thought I would find but didn’t or truths that I knew existed but wanted to rewrite. Rephotograph. Reclaim.

When this restorative process began, first out of therapeutic necessity and then out of pure curiosity, I wasn’t prepared to find—er, accept—some of my family’s truths, mostly because I didn’t know what to make of the bad times and I wasn’t creatively concerned with the good times. Which, by the way, was also a tricked out Chevy van conversion complete with a 10” CRT color TV and built-in VCR that we road-tripped to Hobbs, New Mexico for a basketball tournament in the summer of 1988, when adventure meant returning our Blockbuster rentals a week late and washing our uniforms with Woolite in the motel sink. Those were good times, indeed. And there were many. But the good times aren’t what landed me in therapy twenty years later, pining after answers to the deeply philosophical questions of my youth and the very real traumas of the, well, bad times. And there were many.

I wasn’t supposed to talk about the alcoholism and the anger, the fear, or the confusion, and I’m probably still not. But those truths shaped me into the woman I am today, into the mother I am definitely, just as much as my proclivity for arcade games and the art of sarcasm that seems more biological than environmental. But parsing out the nature versus nurture debate in real time was more than my adolescence could bear, and so I waited, mostly until I could trust myself to handle all possible outcomes, to make proverbial lemonade out of life’s lemons, to rephotograph a carefree childhood that was anything but. So here we are. Of course, I’ve not set out on this trek alone, and I have my friends, family, colleagues, therapist, and you to thank for helping me turn these stories into reality, even if that reality is what I had hoped to find but didn’t.

Daniel George: What was the impetus for this series? Obviously these were lived experiences and represent memories you retain from your childhood, but what prompted your desire to visualize your personal history?

Diane Durant: Honestly, it started as a response to other people wanting to photograph my very deadpan child. When she was three, she stopped smiling for photos because I had already spent all of my mom points on “wait, here, just one more,” and she was done. But because I am just as stubborn as she is, I said, fine, don’t smile. And I leaned into that deadpan aesthetic and the style became our thing. As she got older, she would even laugh and smile before I would take the shot and as soon as we were ready, she would drop her shoulders, settling into the persona, and lose the smile. It almost became a caricature of some perfect mother-daughter relationship that’s epitomized in family snapshots. But that just wasn’t us. This felt more authentic, and it was something we both agreed to. When other people started saying they wanted to photograph her, and also that she looked just like me, I thought, why don’t I photograph her—as me. Then she retains her personhood, doesn’t have an existence mediated by the camera, and I still get to spend this quality time with my kid taking pictures and making memories together. I didn’t know what this series would become until we really embraced it, and she became the character that could portray a part of me that I hadn’t yet come to terms with: the elementary-aged me that had outlived an ontological dilemma and deserved to have her story told.

DG: If I might ask, what is the significance of those particular years—1986-88?

DD: For some emotionally ingrained reason, though I realize it’s not completely accurate, these are the years that I have always identified as the hardest of times. Everything troubling that happened in my youth I’ve always said happened when I was eight. We moved houses and I changed schools, my father was knee-deep in his alcoholism, and the family was in chaos. I was also trying to grow into myself as an individual, and that self did not align with the person that my parents wanted me to become. Even at eight, I knew this to be true. Looking back, I see these years as shaping my opinion of myself and my understanding of the world around me, problematic though it may be. Fortunately, after working on the book, I don’t have the same negative opinion of this time period because I know it made me stronger, whether that was my truth then or it’s the one I’ve created now.

DG: Aside from standing in as the main subject, how did your daughter collaborate in the creation of these images?

DD: Believe it or not, she actually had a lot of say in the development of this project. She even wrote the afterword, which is charming and genuine and frankly fantastic. During the concept phase, I would talk to her about my ideas, tell her about the stories behind them, go through boxes of old clothes and objects with her that my mother had saved, and listen to her feelings about it all. Then when we were shooting, sometimes I used my veto, and I said we were making the image anyway, but then sometimes I would really hear what she was saying, and if she wasn’t into it, we wouldn’t move forward right away. Because she spends half of her time with her dad, I only had every other weekend to plan for shoots, and if the weather was bad or her mood was off, I didn’t force it. It was so important for her to believe in the image and be in the right mindset. After all, she was the main character.

DG: Text plays an important role in this body of work, as well as other portfolios on your website. Could you tell us more about your interest in combining these modes of storytelling?

DD: I love that you referred to the text and images as modes of storytelling. That’s exactly it. Some stories need words, and then some don’t. For this project, I wanted the text and the image to be co-equal; I wanted each to be able to stand alone. That independence is why some pages in the book contain an image of text only. The reader can create their own mental picture in place of a visual that I wasn’t able to accurately reproduce. I’ve studied the image-text relationship for years, and in my work I want to challenge the sufficiency of each mode of representation and embrace the potential that images and text (and objects) have to tell their own stories separately or to contribute to (and even confound) the narratives of the other.

DG: Your captions feel honest, endearing, humorous, and in some cases tragic. What was your experience revisiting and reinterpreting these personal histories—creating new memories?

DD: Working on this project was a very therapeutic experience. When I started, I was focusing on the difficult moments and the sadness my childhood represented—my inability to be fully me. But as the project progressed, and I allowed more memories to surface, I embraced some of the strength that I embodied, the humor I had as a young person, the quirks, the victories. When I look at some of my childhood photos, like the one from my hobo-themed birthday party, I think, that kid was hilarious. And I’m so proud of her. (Not that I think a hobo-themed birthday party is a good idea now, but I loved tramp clowns then and had a real affinity for the Emmett Kelly figurines for sale at our local five and dime.) I wanted all of these attributes depicted in the book in an attempt to portray an honest retelling of this time in my life. It wasn’t all bad, and I needed this creative process to remind me of that reality. Being able to relive and remake each of these truths with my daughter made the experience all the more profound.

DG: You published Stories, 1986-88 with Daylight Books in 2020. Would you talk about your decision to finalize the project in book form?

DD: You know, Stories didn’t start out as a book. It started out as 13 images that remade the “bad times,” and I thought it was finished. I’d photographed my kid-as-me, dealt with some trauma, or so I thought, and didn’t have any more ideas. We’d been shooting for a year, I was in therapy, and the series was done. But after talking to Michael Itkoff at Daylight, we decided that the series could be so much more. In a weekend, I had 30 more ideas. So, for the next two years, I was thinking of each image as part of an even bigger story and imagining how the sequence could work together to tell a truth that readers could experience more intimately. The book as a form is so full of narrative potential, and being able to use each element of the form to retell my story really opened me up to other possibilities. Like the page spreads of Cabbage Patch Kids adoption certificates; the introduction, forward, and afterward; the concept of stories being contained between two hardcovers, wrapped in denim, which really is me in a metaphor.

DG: (bonus question) How is your moonwalk these days?

DD: About as good as it was when I was 10.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026