Isolationism in Photography: Natalie Goulet: Identity Mapping

What does it mean to be alone? To be isolated from the people and things we hold dearest? Since the pandemic, it seems like we all have an answer to this very question. Some people embraced the mandatory isolation while others struggled being forced to be apart from their loved ones. This week will feature photographers who captured moments they felt most alone and the ways this isolation expressed itself in their lives.

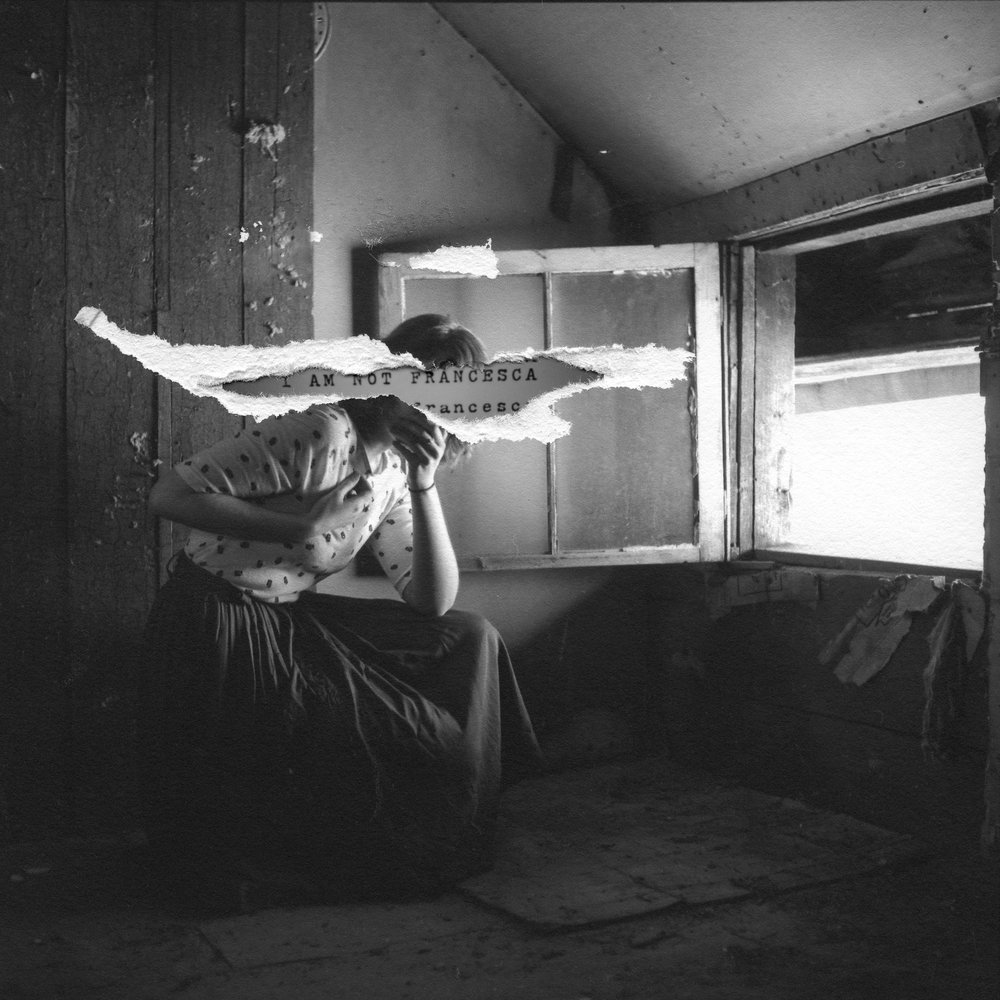

In her exploration of alternative processes, Natalie Michelle Goulet re-imagines her portrait, considering her lineage and memories in connection with how she lost her inner voice. Feeling isolated and cut off from her true self, Goulet placed herself in different scenes – interacting with her self-portrait after it had been taken. This act of interacting with her portrait introduced the idea of reflection outside of one’s mind- how we are isolated within ourselves when we are unable to explore who we are truly meant to be.

Natalie Michelle Goulet is a Canadian artist working within expanded realms of photography and image making. Of Scottish/French settler ancestry, she was raised in Northern Ontario (Treaty 9 territory) and currently resides in Kjipuktuk/Halifax. She holds an MFA from NSCAD University and a BFA in photography and film studies from the University of Ottawa. Her practice, although rooted in analog photography, consists of diverse material explorations, including the use of found objects and performance. Her work often revolves around concepts of instability and entanglement, and seeks an empathic approach to destructive human tendencies.

Follow Natalie Goulet on Instagram: @nataliemichelle.ca

Identity Mapping

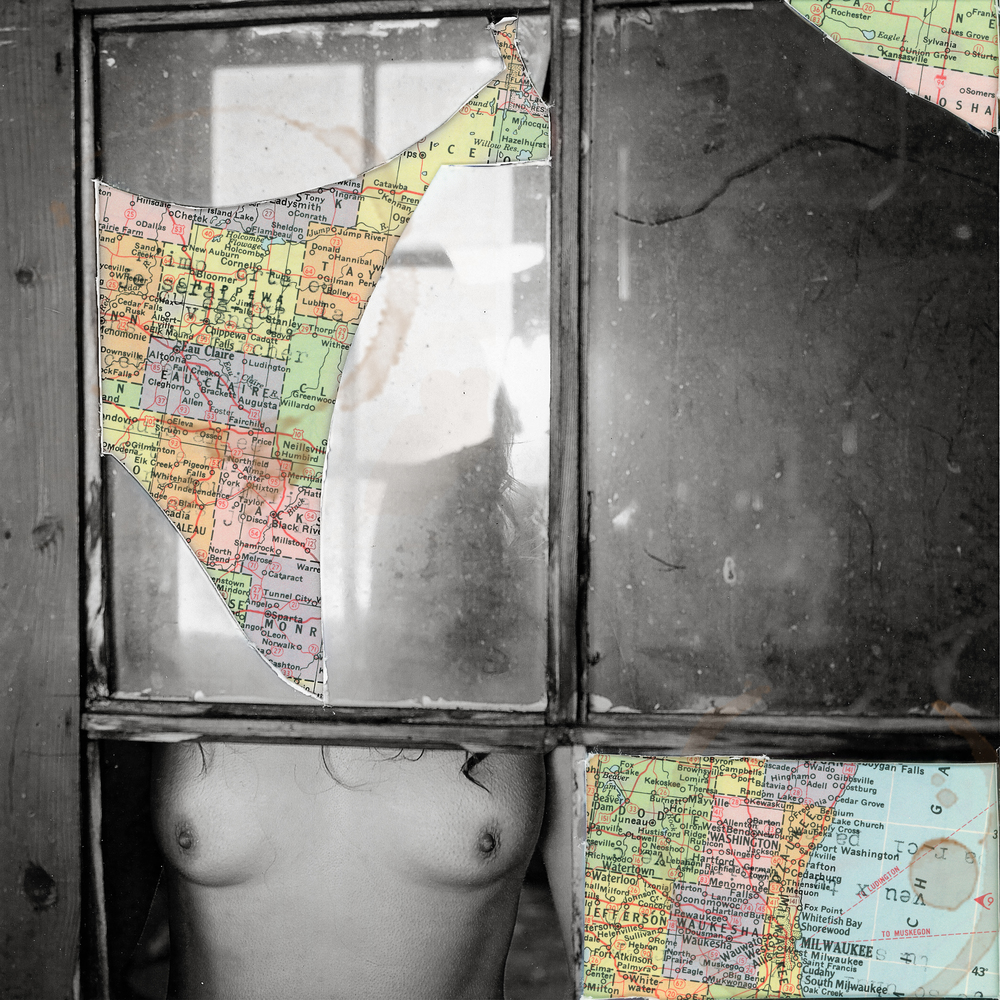

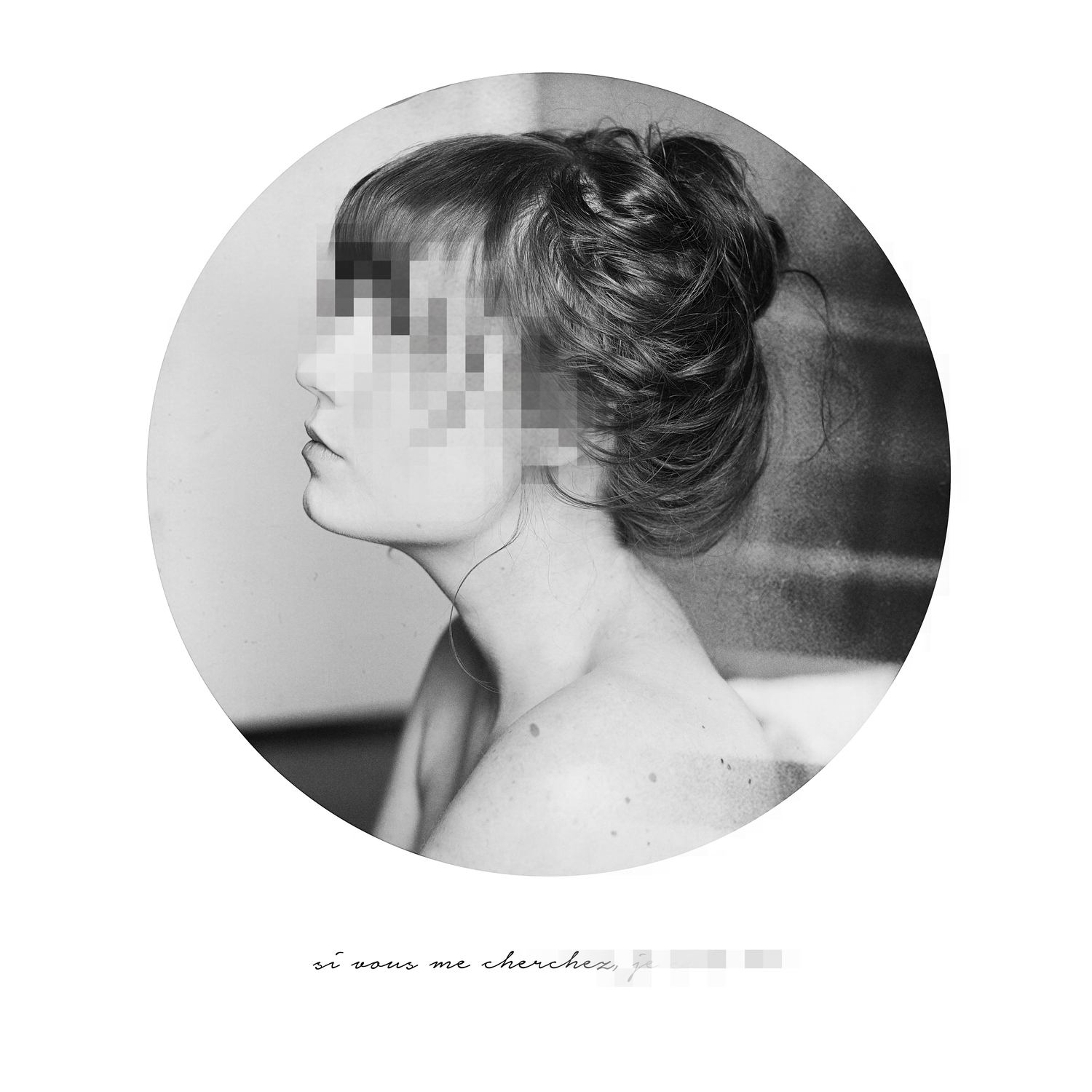

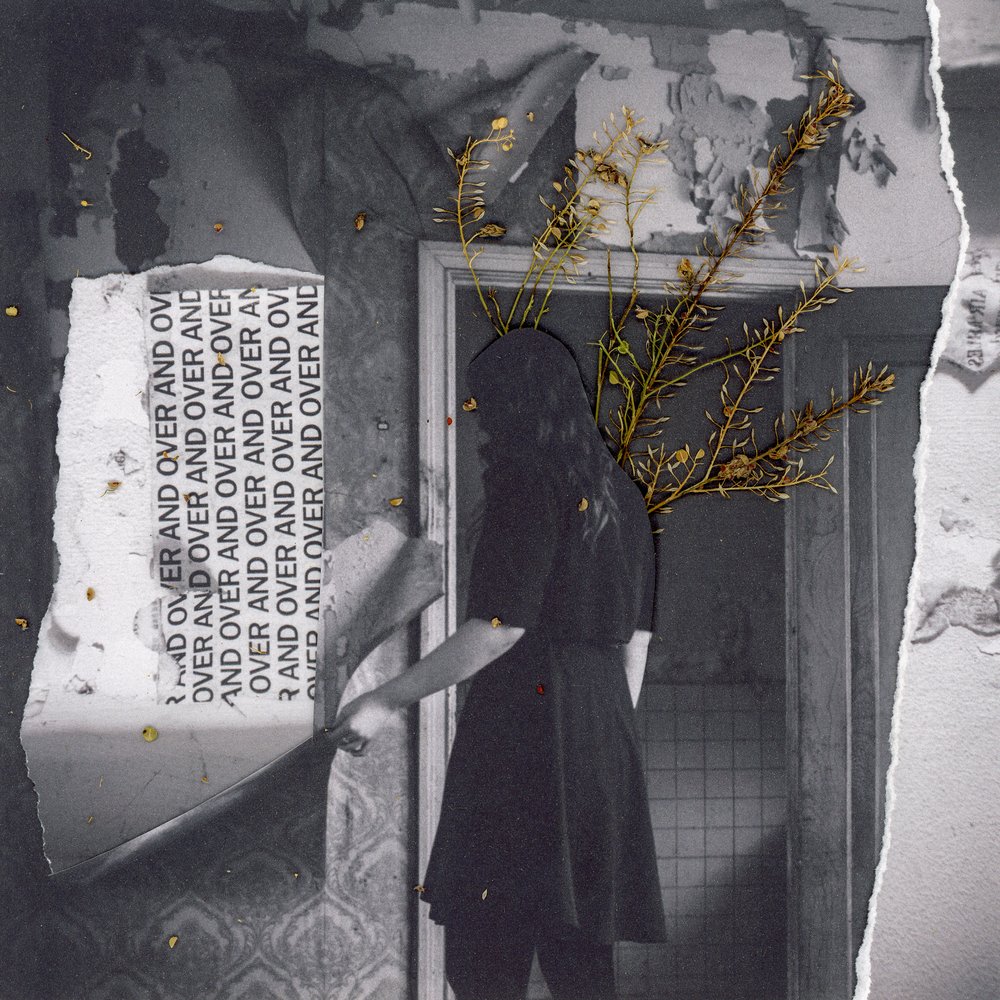

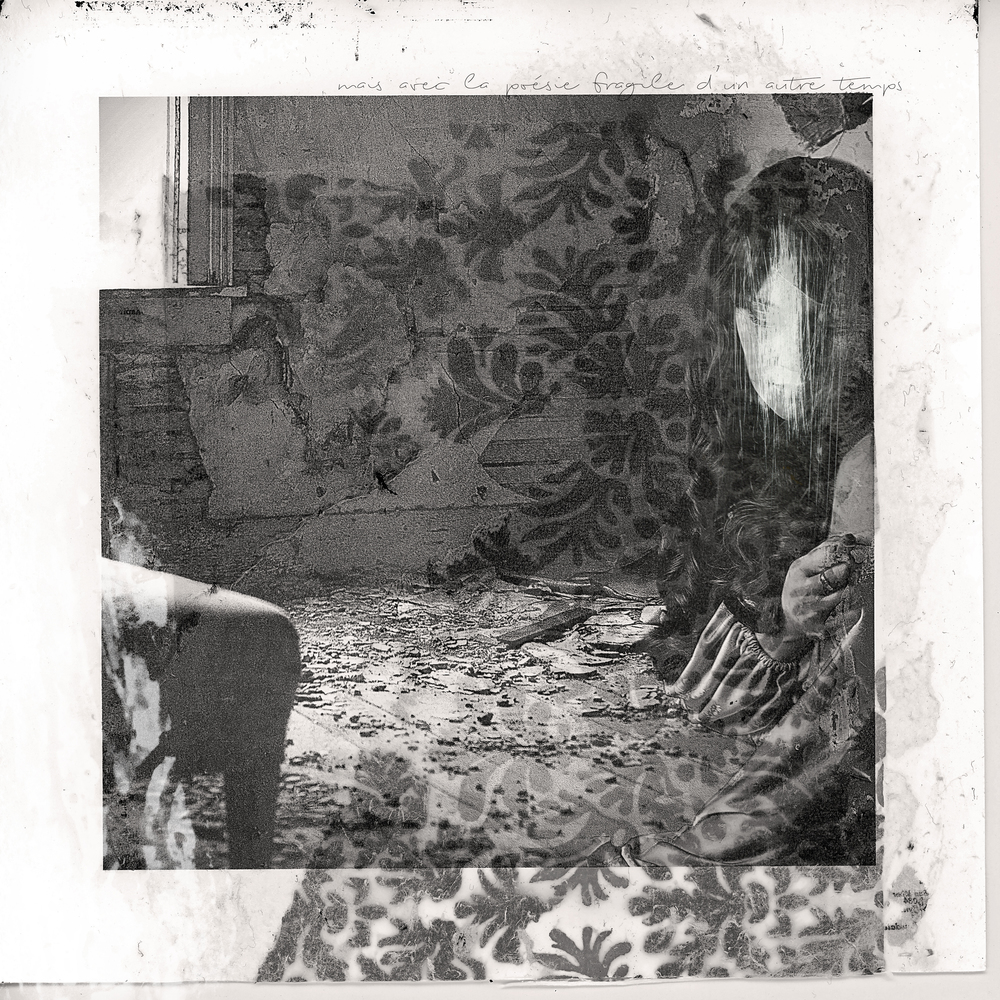

Identity Mapping engages with generational trauma and self-destructive tendencies by employing analog photographic processes with other materials such as plants, maps and text. In this series, I engage with self-portraiture as a vessel to consider the high risk of hereditary mental illness and missing pieces of my ancestral lineage. I piece together fragments of myself throughout the years as I unearth details; places; names of those who came before, and continue to question my position as a neurodivergent settler body. The images are cut, burned, punctured, soaked, ripped, sewn and layered in various ways revealing the manipulated body as interwoven yet disrupted, inconclusive narratives. -Natalie Goulet

Kassandra Eller: I would love to begin by discussing how you found photography. Where did your journey start?

Natalie Goulet: I used to draw and paint, and I dabbled in most mediums before accepting photography as my main thing. As a child I was often allowed to have disposable cameras; those were probably the gateway drug to the lingering interest in analog. I remember being in awe the first time I saw a Polaroid develop, but the film was deemed too expensive. I was lucky enough to have a supportive art teacher in highschool who taught me basic B&W 35mm processing and how to make a pinhole camera out of a shoebox; our classroom had a tiny darkroom with a sink and two enlargers. When I began my undergraduate studies (in Fine Arts), I decided I hated painting and spent my first year in the darkroom. My relationship to photography has strained and shifted over the years, but I am always learning and unlearning, and I’m content overall with the low-toxicity photographic practice I’ve adopted.

KE: As soon as I saw images from this project, I was awestruck. I felt such a deep connection with your work and have explored similar themes in my photography. How did the idea for identity mapping come about?

NG: I grew up in a monoparental situation, and while my mother stretched herself thin to strive to provide the best, it always seemed as though half of my identity was missing or lost in some deep well of obscurity. I struggled with anxiety, depression and chronic

pain from a young age, and suffered through many misdiagnoses and ill-advised prescription drugs. I think I was in a very dark place when I started this work, and it served as a navigation tool towards some form of self-acceptance or understanding. I had reached a point where I wanted to destroy everything I had ever made, and a lot of work didn’t survive, but the remnants were recycled into new pieces.

KE: Were there any artists that inspired you or this project?

NG: In my late teens/early 20s I was producing primarily B&W self portraits on 120 film; so a correlation with Francesca Woodman’s work became fairly frequent. I have profound admiration for Francesca, but it seems as though this juxtaposition mutated into a form of protest to outlive her. Sadly most conversations about her noteworthy body of work always seem to revolve around her death by suicide at the age of 22. My overall pool of inspiration mostly consists of a variety of tenacious women: Louise Bourgeois, Roni Horn, Tacita Dean, Virginia Woolf, bell hooks, Nan Goldin, Suzy Lake, Rosalie Favell, Mary Oliver, to name a few.

KE: This project has a collage aspect because of the different objects you place within the image. Did you have a process or a plan when piecing these images and objects together or did you allow the pieces to come together

naturally? How did you choose which objects to include in these images? Does each object have a significant meaning to you?

NG: I definitely have a propensity to collect things; objects and textures of various nature – mostly small scale. Every so often I have a meticulous plan for the objects I collect, but mostly the convergence of image and object tends to happen fairly organically and

intuitively. I often started by subjecting a self-portrait to some form of maltreatment, then used an object to “repair” or embellish the damage. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, and the object or image gets to take on a new life with a different pairing eventually.

KE: In your statement, you mention using analog photographic processes. In your work, it looks like you use cyanotype processing. Are there other analog processes you use in Identity Mapping? How do these analog

processes create a deeper meaning in your work?

NG: The identity mapping series relies primarily on prints made from 120 film (likely Iflord or ORWO stock.) The film is typically scanned, introducing a hybrid way of working, so there is often a transitory digital component before the images are printed and

physically manipulated. The cyanotype process has been one of my staples for many years; being able to fix an image with water has always fascinated me and is usually conceptually relevant to the work I make. My interest in analog lies in slowness, tactility,

and resisting overproduction. There’s always an underlying interest in transformation that is well-supported by the alchemic nature of analog processes.

KE: In these images, I noticed that we never see a full face looking at us. Many times the face has been destroyed or covered in some way. Why did you choose to “conceal” the face from the viewer and break up the body in this

way?

NG: While this is a very personal project, I think it’s important to acknowledge that I was not, metaphorically speaking, alone in the dark. Not to say that I enjoy hearing that other people suffer through the same things, but a certain level of validation and community is established when someone else relates to the work and wants to open up a conversation. I think that the faceless portraits sometimes act as a mirror and extend a layer of relatability even though these images were initially never meant for public consumption. Removing or manipulating the faces in this way also creates a visible extension between place and body. A portrait can convey a plethora of emotions, but sometimes they tell you too much. I was more interested in the idea of an anti-portrait.

KE: This body of work seems to be a very personal and intimate discussion with yourself. I would love to dive deeper into the process of using yourself as the subject. Why was this choice important to you?

NG: I don’t think it was much of a choice as I wouldn’t want to project my inner-turmoil onto someone else. Self-portraiture has its setbacks and challenges, but also comes with the convenience of availability. Using myself as the subject was also a way of trying to make peace with a faulty family history, and taking the first steps to reflecting on how to be a good ancestor.

KE: I have found that the projects I take on often become a way to process my emotions. It seems as though identity mapping has acted in the same way for you. Did this project become a therapeutic way of understanding the trauma you discuss in your statement?

NG: I think this project arose as a necessary coping mechanism, a way of counter-mapping my self-destructive tendencies. It was a way of questioning and working through a desire to disappear and notions of belonging. Making artwork has always been the most

proactive way for me to process and materialize strong emotions. I probably still need therapy, but making images is cheaper.

KE: Is there anything you are currently working on?

NG: I’m currently in Iceland for a few artist-in-residence programs. I’ve been making a developer from lupine flowers for 4×5 film and photo paper, and undertaking other land-based research experiments. I’m developing a series entitled vatnsstígur /waterpath, which has so far materialized as a collection of installation-based works composed primarily of cyanotype prints and a variety of found objects. I’m hoping to exhibit a more fleshed out continuation of this work in the following year.

KE: Is there anything I didn’t mention that you would like to add?

NG: Thanks so much for your interest in my work!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Steffen DiemerMarch 6th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024